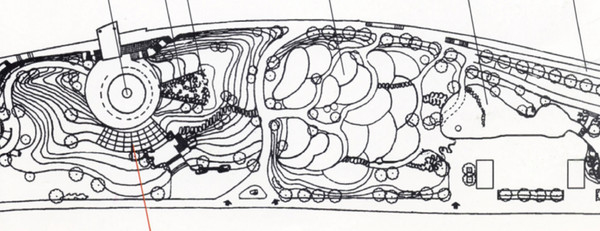

diagram of a Living Water Garden

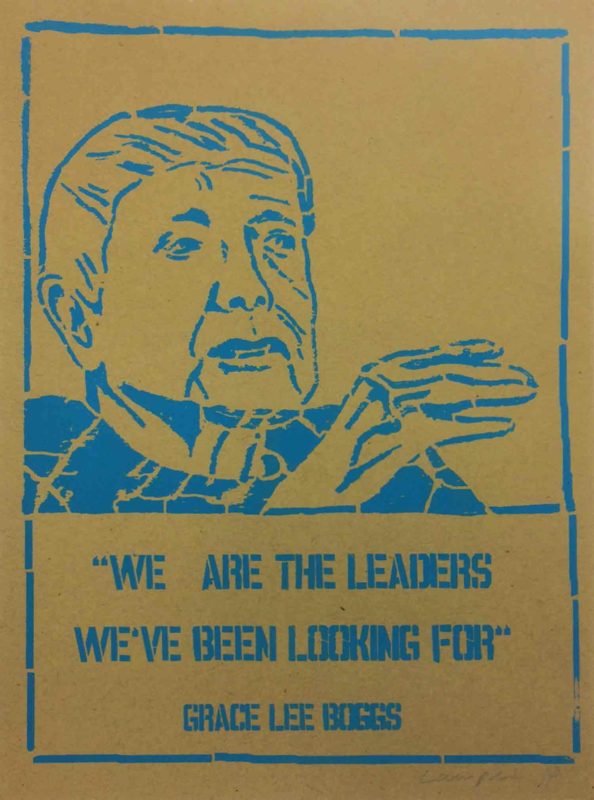

Here is another excerpt from my book A People’s Art History of the United States. This excerpt is on Betsy Damon – an environmental and feminist artist best known for Living Water Gardens – a collaborative form of sculpture and community engagement that aims to restore the damage that industrialism and misplaced priorities has had on fresh water sources. Damon is an absolute force. An artist/activist who lives in Brooklyn and someone who has been at the forefront of addressing water issues through art since the 1980s. This excerpt is from the first section of the chapter.

Living Water: Sustainability Through Collaboration

“Where is your well, your source of water for your home? Who cares for and shares this source? What does your community need to know to protect and restore their water? Why is this information not common knowledge?” —Betsy Damon

Since 1985, Brooklyn-based artist Betsy Damon has raised critical questions through her art and activism about water in the United States and abroad. In 1990, she founded Keepers of the Water, a nonprofit organization that mobilizes artists, scientists, and citizens to collaborate, raise awareness, and ultimately restore water sources throughout the world. Damon’s approach centers on the concept of “living water”—the purest form of a water molecule before it has been contaminated by the industrial landscape. To reverse the damage, a community has to go beyond simply cleaning up polluted waterways; it has to de-industrialize the areas around a water source so that water can function in its most natural state. A community has to allow nature to cleanse the water. Cities rarely do this. Instead, problems caused by industrialization are treated with industrial responses. Dams are built, riverbanks are fortified with metal and cement, and wastewater treatment plants are introduced. All continue to harm water quality, human health, and the overall health of the environment. Damon’s vision differs. She collaborates with the community to create a living water garden— a public park that demonstrates how natural systems can restore a river’s water quality. Her most famous reclamation project took place in China in 1995 on a six-acre site on the Fu-Nan (or Funan) River in Chengdu, a project where activist-based art played a vital role in mobilizing a city and a country to take action. Why did she choose China for her project? And why did her previous efforts to do similar work in the United States run up against a brick wall? Damon explains, “We don’t acknowledge the role [water] plays in our lives. Chinese do, like all people who have a deep history, like Native Americans. People with a deep history understand on a profound level, not a gross level, the importance of water.”

Process and the Underground Artist’s Web

Damon first traveled to China in 1989 with her son, Jon Otto, as a guest artist at a United Nations conference. In 1993, she returned to visit sacred water sites in the remote mountains north of Chengdu. Her search took her on a series of adventures, and she discovered opportunities to learn.

On one journey, she and her son traveled nineteen hours by Jeep up dirt roads to visit a water spring that had belonged to the Tibetans for thousands of years but that was now fenced off with barbed wire and designated by the Chinese government as a future water-bottling company. Tibetans were prohibited from gaining open access to their water source, but they continuously defied the order and cut holes through the fence to drink the water that was so pure, it was believed to cure stomach problems and reduce tumors. The Chinese government wanted to put the water in plastic bottles and sell it, a process that would kill the living-water state of the molecules, further deny the Tibetans their rights to their water, and devastate the ecology of the region.

Damon returned to China in 1995, this time with the intent to create a public art project about the horrid river water quality found in Chengdu, the city where the Fu and Nan Rivers converge. In the 1960s, the Fu-Nan was clean enough to swim in. More than fifty-six species of fish flourished. But as the population of the city grew from two mil- lion to nine million people, the river became a dumping ground. Some 60,000 cubic meters of raw sewage was dumped into the river on a daily basis, and 100,000 people lived in shacks next to the riverbanks. Factories discharged paint, paper, and chemicals into the water. The Fu-Nan became so polluted, the locals nicknamed it “Fulan,” meaning “rotten river.”

In 1985, a natural-sciences teacher in an elementary school in Chengdu inspired his students to take action. The students studied the Fu-Nan and began writing letters to government officials, who responded by launching China’s first large-scale environmental restoration project. Residents and factories were moved away from the banks of the river. The river was dredged; floodwalls were rebuilt; twenty thousand trees were planted; thirty-one miles of parks were established along the rivers, and plans for a future industrial wastewater treatment center were developed. Despite all these efforts, the Fu-Nan still remained polluted.

Damon’s response was to catalyze the residents and the government to take another step. The medium she used to raise awareness was temporary public art projects and performances. In 1995, she arrived in China on a tourist visa with little funding and a single contact, who introduced her to the director of water quality in Chengdu. At the same time, Damon began talking to local artists. She hitchhiked illegally to Tibet to meet with Tibetan artists. Damon recalls:

They [Tibetan artists] came down to Chengdu. By then word had spread in that wonderful way, quietly and through an underground web. Then artists came from Beijing and Shanghai and other cities. We all met twice a week. Everyone had to learn about the life of the river and the history of the river and the science.

Simultaneously, the Chinese government closely monitored Damon’s every move. Police from Beijing interviewed anyone who had spoken or met with her. Finally, the Chengdu city government asked to meet with her. The officials were intrigued by her actions and engaged her in a conversation about the river. They showed her their plans and asked for her opinion. Damon recalls:

Their plan was impressive, but I knew they weren’t going to get a clean river. You build flood control walls and you don’t get a clean river. You dam it and you don’t get a clean river. They were sure they would. I said, “Why don’t you make a living water park to teach your citizens how nature cleans water?” They talked for thirty seconds and turned back to me and asked, “Can you do that?”

Damon’s response was to nod yes.

The city government officials wanted her to abandon the performances and temporary installations and to design a living-water system. They felt that the ephemeral artworks were a waste of time and money. Damon, however, insisted that the performances and temporary installations had to happen. She owed this to the other artists and, of equal importance she felt the performances were an essential part of the process. The government responded by saying that if they liked the performances, they would invite her back to the table and continue the dialogue.

Damon moved forward, brought together twenty artists from China, Tibet, and the United States, and staged twenty-five projects during a two-week series of public artworks and performances on the banks of the Fu-Nan.

The rest of the chapter describes the performances and the Living Water Garden. Here is a visual tour.

The temporary performances led to the building of a Living Water Garden in Chengdu:

To learn more about Betsy Damon’s work, visit her website, here.

http://peoplesarthistoryus.org/

http://justseeds.org/nicolas_lampert/03pahbook.html