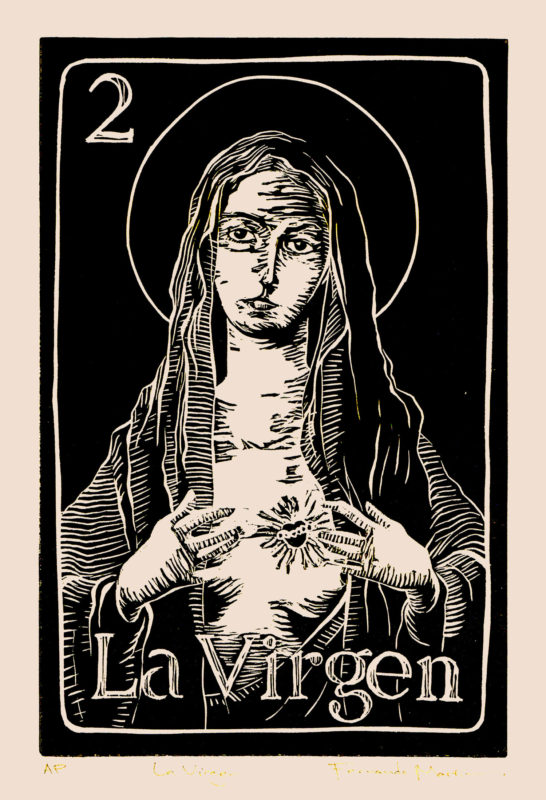

It was beautiful to be with the monumentality of Yolanda’s work last week, her three women, her running women, her Guadalupes, at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, ordinary and everyday women, painted on cheap butcher paper. Those portraits are certainly heroic, larger than life, like we in our work and in our daily lives are heroic, as big as life: working the sewing machines, picking fruit and lettuce in the fields, a chosen familia de mujeres in their homes, running for survival across the academic campus that grudgingly accepts us but doesn’t quite know what to do with us.

The paintings have lived rolled up in the basement of Yolanda’s rent-controlled apartment all these years. I think of the psychology of houses, of Jung’s dream of stairs going deeper into multiple basements, of cellars, of roots, of what we store, and what we excavate.

I think of how we survive as artist-activists, how we do our work with intention. Yolanda, reclaiming and repositioning our ancestral Coatlicues and Guadalupes, facing death threats and broken windows from conservative Catholics for her questioning. I am of a different generation, perhaps, or a different sensibility – what I experience as liberating I find hard to see as threatening. After the exhibit, after scattering Yolanda’s ashes at Chicano Park, we drive past a mass getting out in Barrio Logan, a traditional image of La Virgen de Guadalupe hanging from the church walls. I wonder if they still find Yolanda’s work threatening, if they still want our culture frozen in time.

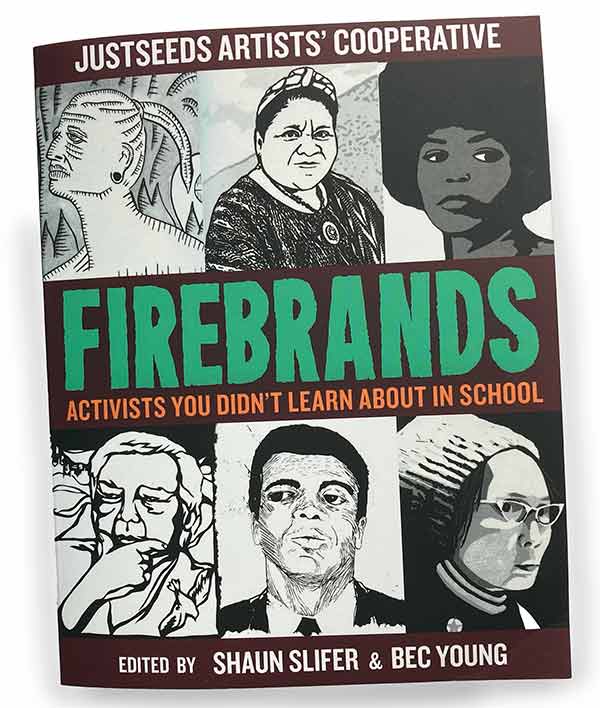

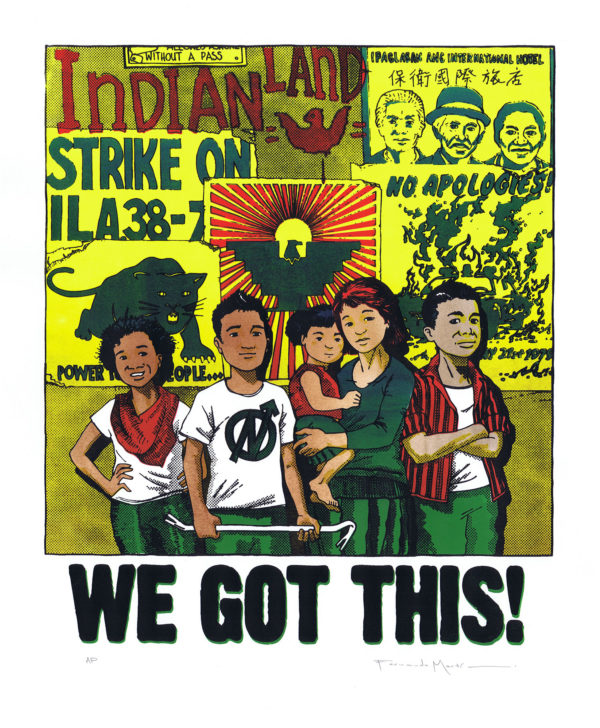

I think of artists who never made it to the level of comfort of big gallery representation and commercial success, and yet, who influenced an entire generation of artists, who gave to their communities, who had to fight off evictions and survive on Social Security. I think of decisions Yolanda made or didn’t make. The most radical decision perhaps, for the late 70s, most feminist: “I am going to move to have a child. I am making that decision, no one else.” She made her choices, to raise a son, to stay in the community, to nurture new voices, to keep the fires burning in our culture to ensure that we stayed real: relevant, questioning, evolving.

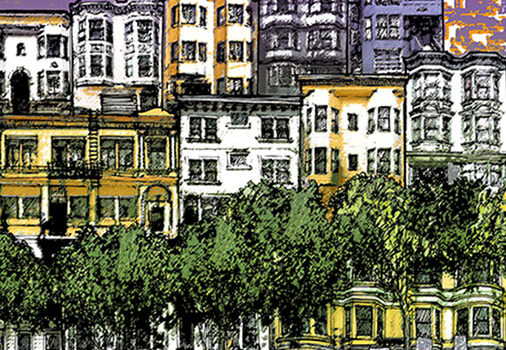

As I write this, my family is facing our own eviction, again. Tatiana Omran saw our home, occupied by tenants, and she and her family decided they wanted it for her to live in. Peter and Tanya Omran run a nonprofit, Heart of Mercy International, that provides aid to displaced refugees in the Middle East. Tatiana’s brothers own a property where two apartments were rented to a corporate rental company that we believe would have made a fine home for Tatiana.

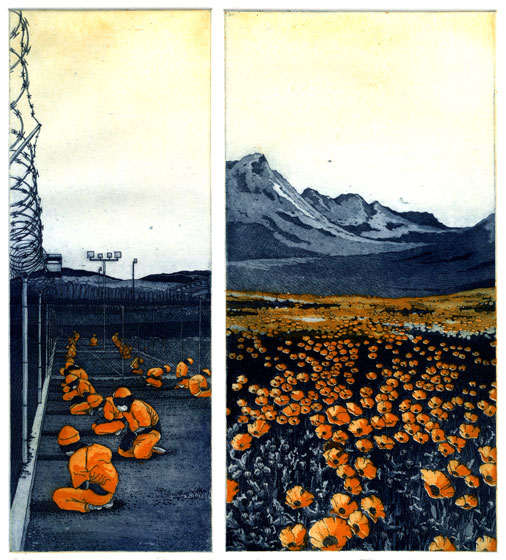

Yolanda counseled me, “This is your life. This is your art. Use it.” Yolanda lived as a renter all her life, facing eviction (twice?) on San Jose Avenue, a few blocks from my own house. As artists, Yolanda Lopez and Rene Yañez made their evictions public for all those who couldn’t speak, who couldn’t share their stories, putting themselves out there, creating art out of an eviction yard sale: “Accessories to an Eviction.”

My partner Michelle and I have made our own choices: the work we have chosen to devote our lives to, how to be in our communities, how to live in a semblance of fullness. Despite our relative college-educated privilege, we, as artists, nonprofit workers and activists, live in a not-so-different precarity from so much of our community, subject to the whims of the lords of land, those who have laid claim to this stolen territory to extract from it the rent that allows the rest of us a place to live and to dream and to create. Off and on, I have lived paycheck to paycheck, without health insurance, with little retirement savings, and still paying off the student loans. Only recently have we actually had a cushion we never had before: if we are evicted and lose our home, we know we will land on our feet, even though we may end up far from our community.

These moments of struggle bring the grief of knowing how little the system values our right – as artists and cultural workers – to live in our city. But the struggle also brings the joy, that in a life well-lived, there’s a community around us, with us, behind us. That was the last lesson Yolanda taught me, as I visited her in hospice, surrounded by her amazing family and all the fellow artists she mentored.

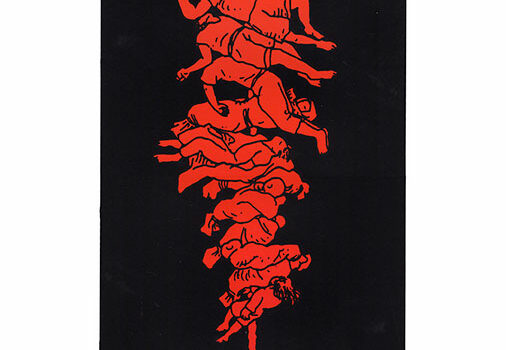

I think of the tenacity of artists, of the way we approach the work. Our lives are our work, our homes are our work. Making art is about the fight, the struggle for life and home. Love and struggle, amor y lucha…

I am chilled to the bone, outraged this is happening to you and simultaneously rejuvenated somehow by your actual writing itself. Brilliantly constructed and urgent…like the pending eviction itself. I have struggled with this myself. I am sending strength and whatever spiritual capital Incan muster.

In solidarity,

Dennis-LeRoy Kangalee

Artist/Critic

NYC