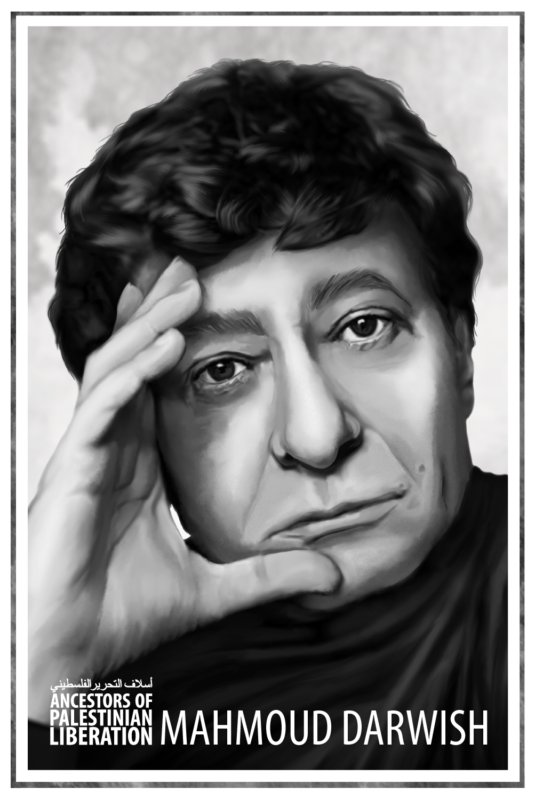

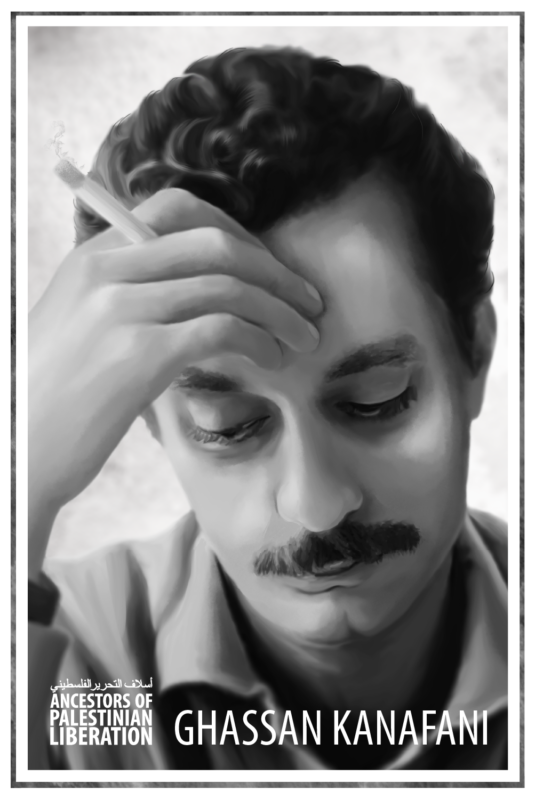

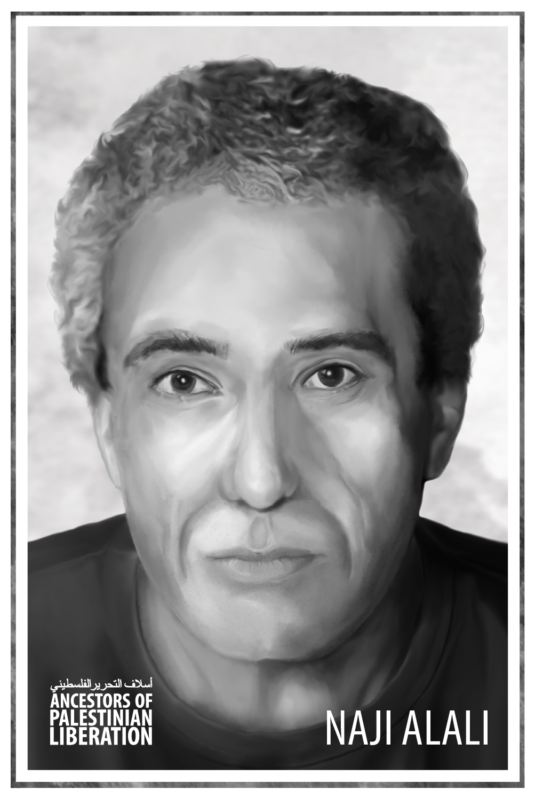

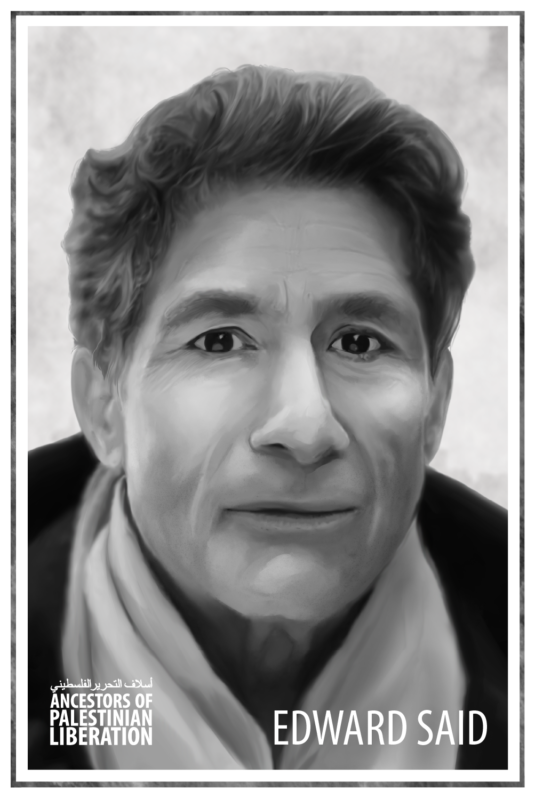

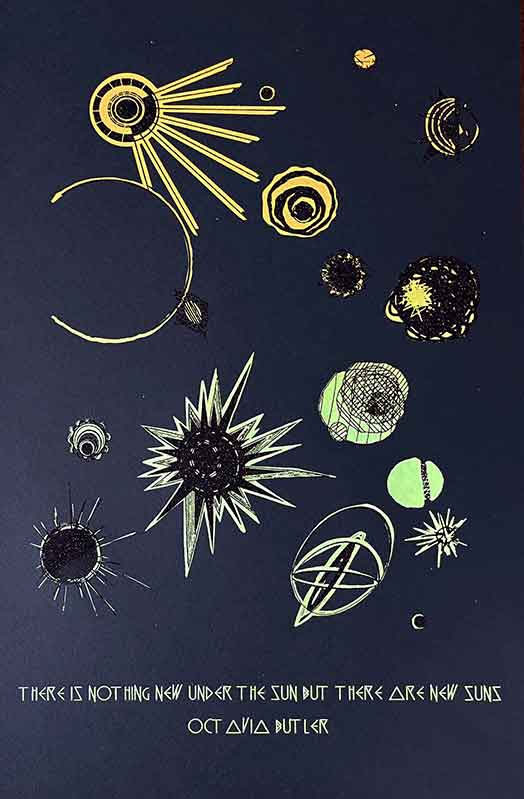

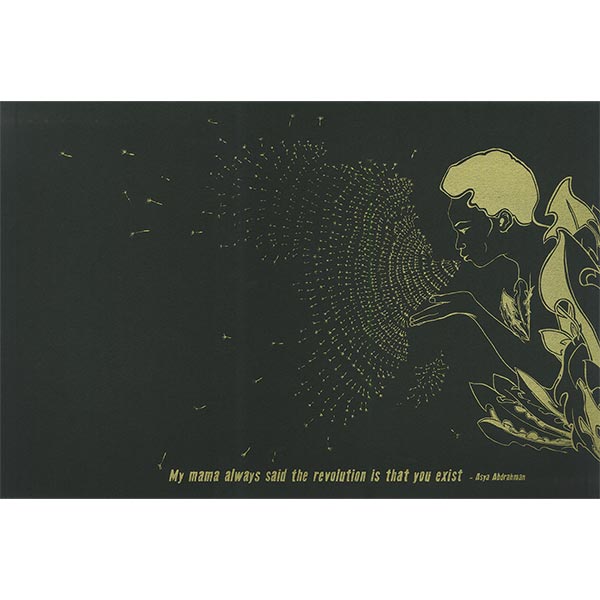

This interview took place in late evening on May 25, 2021 in Portland, Oregon on my back porch around snacks and a pot of tea. This is a highly condensed version of the conversation between myself (Sarah Farahat), artist & filmmaker Zelda Edmunds and three Palestinian friends-Jenna, Mohammed and Ruba. We use Zelda’s digital creative platform “Ancestors of Palestinian Liberation” as an opportunity to talk about the important contributions of Naji Al Ali, Rim Banna, Mahmoud Darwish, Ghassan Kanafani, Razan Al Najjar, Edward W. Said and Fadwa Tuqan on Palestinians today. All of Zelda’s portraits are available for free download via Anemoia Projects. (Ancestors of Palestinian Liberation is a collaboration of Anemoia Projects and Palestine Advocacy Project) All other graphics included are available for purchase or free download via the Justseeds website.

Sarah: Thank you all for being here, in such an intense time to even talk about anything! Do you all want to introduce yourselves and where you’re from?

Jenna: My name is Jenna. I’m from Portland, Oregon. I’m Palestinian American. My family is split between four countries: the United States, Palestine, Jordan and Kuwait. My dad is from a small village سيلة الظهر Silat al-Zahr which is between Jenin and Nablus. They left their homes in 1967 when the Israelis invaded it and that forced them to move to Kuwait. Because of the lack of opportunity in Kuwait, my dad left to [the U.S.] get an education.

Mohammed: I’m Mohammed, and I was born in Gaza and lived most of my life there, and I came here in the US to study and then I got stuck here. Stuck by choice and force, both at the same time. There’s two things. Stuck by force- like, I could not go [to Gaza] and I’ve been waiting for the right paperwork to go home.

If you’ve been following the news, the entirety of Palestine from the river to the sea has been boiling in rejection of the occupation, which includes Gaza of course. We are right now in the aftermath. We’ve been looking yesterday, Jenna and I, at the snapchat world map, and we zoomed into Gaza to see what people are doing, what people are posting on their day to day life. And it’s fascinating. Seeing people barbecuing, and the next slide is like, the rubble, then a building being destroyed. Then next slide is like haircut. Then like an outfit of the day. And the next like a baby, with cute cheeks you want to bite them. [laughter]…people lost thousands of buildings, thousands of houses. Hundreds of people [killed]. Thousands of people got injured. And then you go and tap and see all of these contradictions that life brings us. And you literally see the resilience in a fingers tap. That was uplifting and depressing at the same time.

Ruba: So my name is Ruba. I was born in Jerusalem though all of my life I was never ever ever ever ever to forget that I’m a Hebronite, cause I’m a Hebronite. So my mom and my dad are Hebronites. But my dad grew up in Hebron until the displacement in 1967. They were moved to Bethlehem, which was, know, its neighbor. But my mom, I don’t know when my grandparents were displaced, but I do know that my mom was born in Jericho. Life in Jerusalem is really…it took me years to find the language. I describe Jerusalem as a combination of Jim Crow South plus apartheid South Africa.

Sarah: I was curious to start it off, because as you know, I’m Egyptian, but my language skills aren’t great, and we also have different words for things between countries. I’m curious about the word “ancestor.” I don’t know how the title came about for this project. But also what that feels and means in our Lugha 3rabi [Arabic language.] What’s the translation? Is it direct? or is there another meaning?

Ruba: I think for me personally, “Ancestors” Aslaf (أسلاف)is the Classical way to say it. It’s very familiar to my ear, I just don’t say it. What I’m saying and hearing more is Jdood Jdoodi, like “my grandparents’ grandparents.” That’s what I’m used to saying or hearing, more than Aslafi.

Sarah: Do these people fall into that context, or do you call them shahid (martyrs/witnesses)? Do you know what I’m saying? Would they be considered in Arabic, would people refer to Ghassan Kanafani as Jdood Jdoodi or shahid…?

Mohammed: Here’s why language is a mf’er! [laughter] …So if I want to talk about the people that came before us, or the people that lived before us, what their life was and what they are telling us through their life experience- I feel like- when we talk about that, we liberate ourselves from etymology and meanings, all of it you know. I don’t care what the title is…it can mean something and can be politicized and weaponized [anyways]. But I’ll stick to “the people who came before us.” And in that sense, and that way, those people lived and lost their life, and we’re still alive. So we will get inspired by them. We will get influenced by them.

Sarah: And that’s Aslaf?

Ruba: It engulfs all of it. And Aslaf, one of the Aslaf can be a Shahid and one can’t. You know what I mean?

Mohammed: Shahid in Arabic is ‘witness’ and witness in that sense, yeah they witnessed the Palestinian dream. They witnessed its progression. And in that sense all of us are witnesses. And like all of us are, shuhada in that sense. So as long as you acknowledge what’s going on and willing to say, willing to tell, you are yourself a witness.

Zelda: What do either of these Mahmoud Darwish quotes mean to you, and how does your identity as a Palestinian in the diaspora impact your interpretation? The two quotes are:

We have on this earth what makes life worth living.

على هذه الأرض ما يستحق الحياة

And then separately:

We suffer from an incurable disease called hope.

نعاني من مرض عضال اسمه الأمَل

Jenna: I can actually speak to the Mahmoud Darwish quotes ’cause he was one of the first poets thats really led me on my path to exploring my Palestinian identity. Especially in high school. His poetry books were the first things that I read from a Palestinian writer. And so that had a really profound impact on me, especially like, he could so accurately articulate how all Palestinians feel across the world.

And I’ve also been thinking about this quote- we have on this earth what makes life worth living– and maybe the modern version of that, which is like in the 47 Soul song [Mo Light]- ‘they’ve seen us alive’...That’s what they hate. They hate that they see us alive. They hate that we express joy, happiness, like, the things that come with our lives. Whether it’s the good or the bad, and that I think is just something that they hate. They can make your life so miserable, but you still have these small joys. Even when we were looking at the snapchat Gaza map, you saw, despite the destruction, the rubble, these Palestinians showing off their outfits, showing off their haircuts, showing off their cute babies, going about their day just because they have to. I think the State of Israel really hates…that even though they can try and make your life so miserable and unbearable, they can’t take away what brings us happiness and life.

Sarah: “We teach life sir.”

Ruba After Oslo, everything that came with [the PLO] was blacklisted [in my house]. I was nine, guys. So I never got to enjoy what Mahmoud Darwish had to give when I was young, it was not part of my influence. What I was influenced by was Naji al Ali and Ghassan Kanafani, [they] were alive in my house.

My mom loved Naji al Ali, and she had…all of his political cartoons…She’d speak of him, she’d quote him…Ghassan Kanafani, same, we had his books and I loved reading. His books were easy enough for me even when I was a kid…his books were captivating. They stayed with me. When I became a teacher, I explained Palestine to first graders through Returning to Haifa | عائد الى حيفا A’id lla Hayfa. ‘Cause [living in Jerusalem] you were not to talk about Falastin or Nakba day- its their ‘independence day’. So how do you explain to a first grader how gaslighting the situation is outside of this classroom? And how it doesn’t match anything, anything. Ala’ al Haifa…it’s a kids story- about a kid who was not with his family. And how they came back and he was a stranger to them. It’s a story that explains our story. And I feel like Ghassan spoke to me since I was a very young person.

Sarah: How was Naji’s work disseminated in Gaza, or in Jerusalem-what did that look like? Originally, how was his work disseminated, how did people learn about his work? Was he published in papers under ground papers, like I don’t really know.

Ruba: As far as I know he was published by Dar Altan, ….

Mohammed: (The Kuwait Newspaper)

Zelda: and Al Horreyya Newspaper…

Ruba: There were a few who published those things. There was, in the first intifada, there were a few inside. After that they were gone.

Mohammed: Brochures, fliers, hand to hand- literally. And you can get arrested by sharing these.

Ruba: Zaid al Quds would until he couldn’t. I feel like now we’re seeing in glimpses what used to be that defiance of the first Intifada. Which is – we’re not allowed to do it, but we’re gonna do it.

Mohammed: Like, fliers, graffiti, You’d see Handala everywhere. Even now in Gaza, wherever you walk you find a Handala, graffiti just there.

Ruba: And in Jerusalem, and in Ramallah and in Haifa and in Nasra, and in every fucking place. Until Falastin [Palestine] is free he’ll forever be looking, with his hands back, not approving of any of this shit.

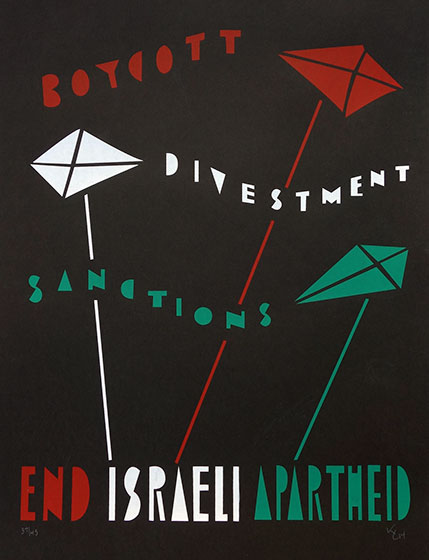

Mohammed: Even the BDS movement right now has Handala on the logo.

Ruba: They did the worse thing by assassinating a free speaker who was in Exile. To go back to the Mahmoud Darwish [quote] Oh wow, so my mere existence upsets you? It’s worth living for. It’s so worth living for. If all I can do is be alive and you’re that pissed, I’m doing something right!

Mohammed: Mahmoud Darwish wrote our story, because usually we’re not depicted as the victorious. And history always acknowledge the stories of the victorious, not the victims. And Mahmoud Darwish made sure that our history is documented with our highs and our lows…Nobody looked at the human in us before reading Mahmoud Darwish….I grew up with Mahmoud Darwish, thinking that he’s a legend. I remember one time when I was a kid, I was like, how’s this person alive? When I was in like third grade I was like- oh Mahmoud Darwish is alive- shit! Like we could actually see him. You know like, that person has that much presence that you don’t assume that they’re alive. Because they have that much. When you bring their name, they have that glow, that halo. So I don’t think he needs a definition or anything. But I think his existence, not just his quotations, we all grow up with his poetry being sung by Marcel Khalife, and then Rim Banna. [Darwish] told our story on our own terms. He taught us a lot about all the other issues that we would not usually know about, because we’re so drown in our own misery and occupation and life.

But he drew our attention to the Native American struggle. He drew our attention to other struggles in the world. He brought our attention to the white man. And without even having us to read all of these thick history books. He effortlessly brought Palestine to us in a global way. And brought Palestine on the map in his own way and sense. And he’s cool. He’s fun. He’s flawless.

Sarah: I mean it’s beautiful right? They aren’t saints. They’re humans and they’re complicated. And the relationships everyone has to them are complicated.

Zelda: I want to pose a question off of something you were just talking about Mohammed. Mahmoud Darwish and Edward Said worked really closely. And so I think some of what they brought has similarities. In what innovative ways do Palestinians take back their right, or you take back your right to narrate your own stories today?

Mohammed: I mean Edward Said, lived here. He saw it all…being here, being in the Big Apple. He had the perfect platform to speak and I think he did what anybody in his place will say- we exist and we want to tell our stories. And he himself and his office got attacked for saying so. He had to flee his office multiple times at Columbia University.

Edward Said didn’t have to have someone translate his words. He inspired Palestinians. When you read his memoir…you would see that in his core, he’s like any other Palestinian. He want the right for return, he want to tell our story, and that’s further from anytime of book or fancy words and anything else. I like listening to him playing the piano in Gaza…All of these people, except Razan because she didn’t get the chance, have criticized and help correct the Palestinian peoples choices and ways, in one way or another. Edward Said didn’t agree with everything the Palestinian people have done, but he helped us as a collective as much as he can..It’s not just like we are glorifying those people because they’re worth glorifying. But also, they played active role of telling us, “hey wake up!”

Ruba: Reminding us of what unites us too.

Mohammed: Or what’s an issue that we should not negotiate on. That actually makes me super sad looking at Razan. Razan is, she was a baby. She’s a baby. To put her in such a high place as an ancestor, is painful, you know. She shouldn’t be there. She should be one of us at this table, talking about those situations. Those people lived their lives.

Ruba: We’re all older than her.

Mohammed: I’m not talking literally, but yeah we are. So in that sense, we put her as an ancestor, and she is. But it’s devastating to see her there. But what she’s telling us is, Palestinian people from the youngest to the oldest are gonna tell their story by where they are. She was on the front lines, helping the Palestinian people on the border, marching for the right of return. Which was not on the map for the last 20 years, until the March of Return on Gaza. And everybody, every newspaper in the world start talking about the Right of Return as if it was yesterday. She put the Right of Return back on the map. She put the cruelty of the occupation back on the map. She was just a nurse in training, with her white coat being there, and she was killed for that. And it’s devastating, but she’s telling us that no matter how old we are, no matter where we are, we’re gonna tell our story, because that’s what matters, and we’re here. And the people who lost their house in 1948, are still here. They just have different faces, but the same people.

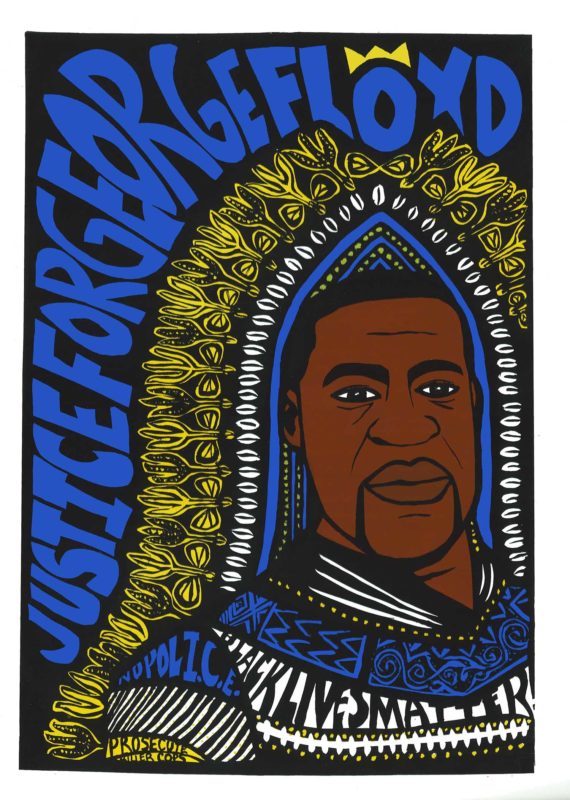

Sarah: I mean, today is the one year anniversary of George Floyd’s murder. And he’s also an ancestor now. Not by choice.

Ruba: Razan and George Floyd are ancestors, but not by choice.

Mohammed: They shouldn’t be. They should be with us at the table.

Sarah: And both killed by state violence. I’m curious of any parallels you see in terms of the Black struggle here in the states and the Palestinian struggle.

Mohammed: I would not say it’s the same. I’m always recognizing that every people’s struggle is unique to them. But I always draw on the similarities because that’s what we can do. It’s easy to say, oh we’re the same- no we’re not! Nobody [in Palestine] has been enslaved for hundreds of years and been brought from their land to be here, and forced to build a country and then been treated as like a third class or fifth class citizen.

Our suffering is different. But there’s these similarities- like the people and the police here who treat Black people with this inhumane treatment- got trained under the Israeli army, and got trained under the Israeli defense system. The surveillance cameras, surveillance systems, surveillance methodology that American police and state systematically use [against] Black people here, and force them to submit, and force them to be basically tenth class human in the US, are being imported and tested on Palestinian people.

It’s easy to find [on the internet]- when the uprising in Ferguson happened, and the Black marchers were being hit with the tear gas bombs, one of the photos circulating on the internet was of a tear gassing. Palestinian people saw it and recognized it and started tweeting at the Ferguson people marching, saying, ‘this is the same [tear gas] we’ve been hit with and this is how you treat it’…[that] speaks volumes and volumes about those similarities, and we don’t have to. We both have arms and legs and we both know what injustice means. And that’s enough.

Ruba: I feel like the bigger picture is, we’re struggling together. I find that everywhere people feel each others struggle, and that’s a language way higher than any word we can talk about. It’s very much deeper than any language, whether it be in our beautiful Arabic, or our limited English, the things that connect us are felt more than spoken.

Sarah: Are you saying, the politicization of young people here [in the U.S] during this last summer of uprisings, has in some ways primed that same group of people to be more media savvy in whats happening in Falastin?

Mohammed: More critical, yeah.

Ruba: And this friend would give the baton to another friend, who would give the baton to another friend, who’d give the baton to another friend. Literally who we’re following [on social media] are just human beings who are having a phone going live [on the ground in Palestine]. Knowing that they may be shut off, and somebody else will do it…It’s…it’s so inspiring.

Mohammed: It’s our new poetry.

Zelda: Related to interconnected but distinct struggles, I wanna ask a question- ’cause Fadwa Tuqan’s work was so good at criticizing colonization and occupation, but also patriarchy. She was really intentional in that. And so I want to throw this question to Jenna first, You can also pass the baton. [laughter]. How have women bridged the duel struggles of combating Israeli colonization, which is inherently gendered and patriarchal, and transforming their own communities away from patriarchal norms and system?

Jenna: I think it’s a really hard question. ‘Cause I have really complicated and incomplete thoughts about it. And I’ve personally been struggling with being a Palestinian woman doing activism, doing labor in organizing spaces that often get pushed on women, and really thinking about that. And also, the image of Palestinian women in our communities, I’ve been really trying to break that down more because at the same time- yes Palestinian women first and foremost maintain our culture and pass it down. But that’s also a heavy burden to carry. It’s really hard, cause at the same time, I want to be my complete self and live my life, and also not live in a patriarchal society which I live in here [U.S.]. But I also live that way in Palestine.. But I really think that Palestine is free when we are all able to express ourselves freely. And that includes not being fetishized in a weird way which is how I feel, that happens sometimes. Whether it’s the image of Palestinian women in thobes, Palestinian women with guns, or even Palestinian movies that are directing to a diaspora audience, it’s actually weird- Mohammed and I had this conversation where he pointed out where like, in a lot of these movies, the Palestinian woman is a passive character. I think the only one where she’s an active role is in Salt of the Sea. And a lot of these films are made by Palestinian women too. What does that say about how we’re representing ourselves if we’re like simultaneously being like…the ‘mother of Palestine’. Sometimes I’m disgusted by that image. It triggers me sometimes when people like Sliman Mansour [depict] Palestine coming out of a women’s vagina…I really struggle with it. Cause at a certain point in my life, that image meant a lot to me. But even now as I’m more of an adult woman, and thinking about having kids, I’m like,’this is too much pressure now!’

Sarah: ‘I just wanna have a baby, not the whole of Palestine!’ [laughter]

Jenna: Not the whole nation! [laughter]. It’s really complicated right now for me, I think at this point in my life, because i want to be myself, I want to be Palestinian, I identify as a woman, and its really hard I think right now at this stage in my life, and like wanting to do things I like- which are Palestinian things-cooking Palestinian food, doing Palestinian embroidery, exploring that part of my past. But sometimes I don’t also want that pressure of doing other things. It’s really hard right now for me, because I feel there’s a lot of pressure to be a specific type of Palestinian woman and sometimes I don’t want to be that.

Sarah: Do you think that’s coming from the occupation, or from the patriarchy, or combination of those two things?

Jenna: I think its a combination of nostalgia…I think it’s mostly the patriarchy that like makes us look through the specific lens, and then it’s reinforced in a social media cycle.

Sarah: How does Tuqan’s work challenge these norms or the internalization of the patriarchy, or oppression, or the atmosphere or image of what it means to be a Palestinian woman? Is that a part of her work that you resonate with?

Ruba: I heard of her when I was young, and she’s side-noted. The reason I know about her is because we had a few feminists in our school- like the teachers. Yes, she occupied a paragraph, but Mahmoud Darwish and Naji… when people… like theres a different kinda talk when you hear about Ghassan Kanafani. You know, Footnotes on Fadwa…She’s mentioned only in literature, not as a person who did anything to change anything.

Mohammed: It speaks a lot to how women are being treated in the media, the magazines. But also, we’re talking about somebody who was born in the same year that the Balfour Declaration was written in, [1917]. So media at that time, the first generation of the Palestinian poets, did not get the same treatment, as the second generation, like Mahmoud Darwish and others.

Sarah: She was really a trail blazer.

Mohammed: She is always in the shadow of Ibrahim Tuqan, her brother. But at the same time, he was a critical point in her education. She was not educated and he was the person who taught her how to read and write, give her books, give her all of the means that she needed in terms of poetry. And she was publishing in magazines and newspapers under a pseudonym. On a technical level, she’s amazing in terms of- she wrote poetry in all of its forms. She wrote the regular classical, two pillar type of poetry, and then she wrote the الشعر المربع (Form of poetry) Moraba3, and شعر التفعيلة tafalia , and then the free form and the articles, and she lived, imagine how much experience she’d get from 1917 to 2003! She was a challenge by existence, by herself. not just for the Israelis only, but like for the Palestinian community, Palestinian publishing industry. Her own family.

Sarah: You gave me the tools, and I’m gonna do all of this as good as I can. Better than you.

Mohammed: Yeah, so that’s amazing. And whenever I remember her I always remember whats engraved on her tombstone.

Zelda: I have it here:

Enough for me

Enough for me to die on her earth

To melt and vanish into her soil

Be buried in her

Then sprout forth as a flower played with by a child from my country.

كفاني أموت على أرضها

وأُدفن فيها

وتحت ثراها أذوب وأفنى

وأُبعثُ عشبا على أرضها

وأُبعثُ زهرة

تعيثُ بها كفُّ طفل نمته بلادي

-Fadwa Touqan

Ruba: There was a hashtag on Palestine being a feminist cause. My brother had a whole discussion with my cousin about it ’cause he was pissed off. He was like, ‘why do they have to put feminism in everything?’ [laughter].

Sarah: We saw Naila and the Uprising, and I loved it. That was the first film I had seen that really highlighted (at least that was translated into English…) the women’s huge role in the struggle for [Palestinian] liberation.

Ruba: [Women and girls are] now the ones leading, the men are getting arrested. The women are making the seminars for what to do, what are your rights, they are in the front. They are the ones being the reporters, because, they know they can arrest a man but a woman would look optically worse for Israel.

Sarah: And so, speaking of women in the front, what are some songs or thoughts about Rim Banna and how she has continued that complication and broadened what women can do with their voice?

Ruba: She sings to the soul, oh my god!

Mohammed: I mean she was one of the … she started in the 80’s…around when the first Intifada started. She lived in [occupied] Galilee. So she was like singing and going, and she would always be either arrested or her events will be taken down because she’s the one who’s singing. And at that time when she started, she did not start with singing the big names or anything, she was like um, we’ll sing the children’s songs.

She was one of the first Falistini [Palestinians] who also also broke the [barrier] between the Palestinians who live inside historic Palestine, the Arab world and the Palestinians who live in Gaza and the West Bank, way before everybody else. She did the first Skype concert. She did a concert from her bedroom inside her house [all the way] to Morocco.

Sarah: Such a visionary!

Mohammed: She was the first person who was like, if you’re not gonna give me the visa or let me leave, I’m gonna continue and do the thing. You’d see her on a giant projector at a giant festival in Morocco being projected there, and just playing with her guitar. Not just about how sweet her voice is, or how visionary she is, or how she died, or how she’s iconic. She has the Palestinian soul in her, which is – “How can I be, no matter what?”…And now my favorite album from her is April Blossoms– collection of childrens’ songs inspired from our folk songs- from those little things that come and tell us about who we are without having to use fancy terms, fancy words…complicated language and complicated terms. Because that’s really who we are. That’s the bare of our soul.

Zelda: Thinking about how Banna held onto the past, and brings it into the future through her art, through her music. What special ways have you and/or your family held onto Palestinian culture and bringing that into the future?

Ruba: Like, in what way haven’t we? [laughter]…For me, it’s seriously in everything. I could be smelling an orange and then remembering my dad putting the orange peels on the soba7, when it’s winter…So much of Oregon reminds me, so much of the little spring flowers. When I first came to the US I remember how hiking around Oregon and the gorge, especially seeing Oregon, that it had an ocean and has the rivers, and has a mountain thats so high and snowy. And it has a desert. And I’m like, oh my god, this is what they talked about Palestine being- a little piece of earth that has almost everything, which it really actually does. It’s so fucking incredible. It’s really fascinating that in the middle of the Middle East there’s this snowy mountain.

Sarah: Plus a floating sea…

Ruba: Plus the lowest point on earth. Like wow!

Zelda: Thank you for recovering my poorly worded question with a fabulous answer [laughter].

by Josh MacPhee

Ruba: It’s in kulshi, it’s in everything.

Mohammed: And it’s ever evolving. We keep stories from our stories and from [our] parents, and talking about ancestry. I’m not sure if this is the same, but I remember when I first met one of our friends…because I needed a kuffiya to wear at my graduation, and I met him and what I saw, he has the Falastin map and flag. And It was like the first time to see a Palestinian in the diaspora in their natural habitat per say. And I was terrified, because, am I gonna end up being a person with a flag and a map? Is Palestine gonna end up being that?

It was fucking scary. I couldn’t stop thinking about it for years and years, until now. I have a couple Palestinian flags in my house. But can you imagine, you come all the way and you end up putting a map and a flag and going on? It’s terrifying to me. Because it’s not a map, it’s not a flag. It’s not a symbol, it’s not even Handala…it’s everything… there’s nothing wrong with a flag and a map. But witnessing it, the act of seeing it and clash with it for the first time is terrifying. That’s the evolution. It’s like, we did not just happen. We’ve been for a long time. And we’re gonna continue being, and we’re more than a flag and a map, we’re more than a movie, we’re more than a picture, we’re more than a person, we are we.

Download PDF Transcription Below. A voice accessible mp3 will be coming shortly.