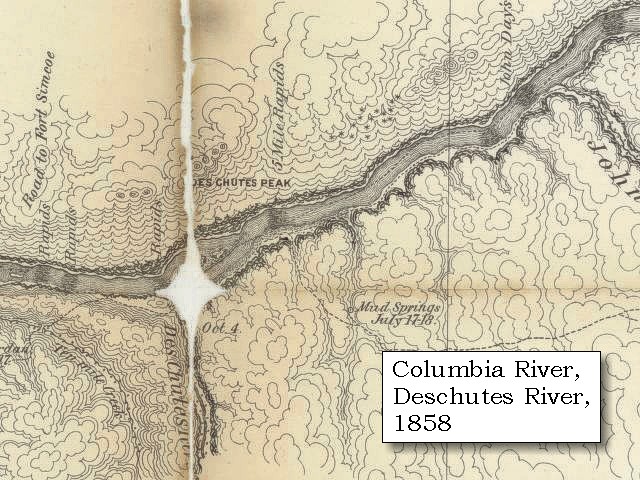

For the past few weeks I’ve been carving a 4 foot by 6 foot block of birch plywood, depicting a section of the Columbia River Gorge. I live about half a mile from the river in Portland, and the Gorge starts about twelve miles to the east. It’s a dramatic channel cut deep into the basalt of the Columbia Plateau by a series of ice age floods, released after massive ice dams broke many hundreds of miles upstream in what is now Montana. The floods scoured the landscape over a thousand years or more, forming the dramatic cliffs draped with moss and slit with waterfalls that can be seen today.

The Maryhill Museum is an old mansion in the Gorge full of art and artifacts, and the curator there, Lou Palermo, had an idea last year to recruit 11 printmakers from the region to work with communities along the length of the Gorge, from the confluence with the Willamette in Portland to the confluence with the Snake near the border with Idaho, to interpret the shape, history, and culture of the place. The name is a nod to the Surrealist parlor game Exquisite Corpse, where artists follow the work of other artists without being able to see what came before them. I applied.

I was assigned section seven, which begins at the point where the Deschutes river meets the Columbia and ends just beyond the John Day dam, where the John Day River joins the flow. I drove out to collect my block and to visit the area last month, driving past the Dalles dam and past the slackwater lake which drowned the oldest continuously inhabited site in North America- Celilo Falls. This was a gathering point for people for tens of thousands of years prior to the arrival of settlers, a place of migration and an almost incalculable salmon harvest. Now the falls are seventy feet underwater, and the lake that covers them backs up into the area I had been assigned, flooding many ancient sites and much stone-carved riverside artwork.

The Columbia is dammed all to hell, resembling an axe-cut snake writhing across the northwestern quarter of the continent. The dams were justified as clean power generators, and aluminum smelters pumping out ingots for the aviation industry and our numerous wars were built in the shadow of some of them (like the John Day). I drove out to the dam to see what it looked like on the Washington side. The riverbanks were lined with people fishing from platforms, much as they might have done at any point in the last several millenia, and others relaxing in lawnchairs monitoring lines of rods bobbing gently in the slack waves ebbing out from the spillway. The dam was glum and noisy. The aluminum smelter had been demolished and was now just a white square of dusty concrete about a kilometer on a side. The torn black basalt of the river basin poked out through grasses and buckwheats, tufted flowers waving in the wind turning the new turbines up on the ridge. I drove back to the state park and put up my hammock and read some book.

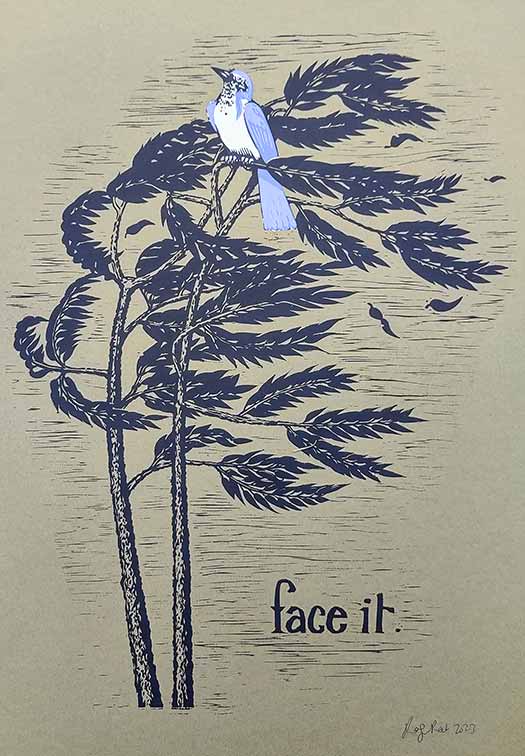

When I got the block home I set it up in the garage and spent a long time trying to figure out what I was going to put on it. Too many stories, and none of them mine! I decided on a story as old as I could find- the lives on non-humans, present and extirpated, because I usually find that those help say the things I want to say without me saying them.

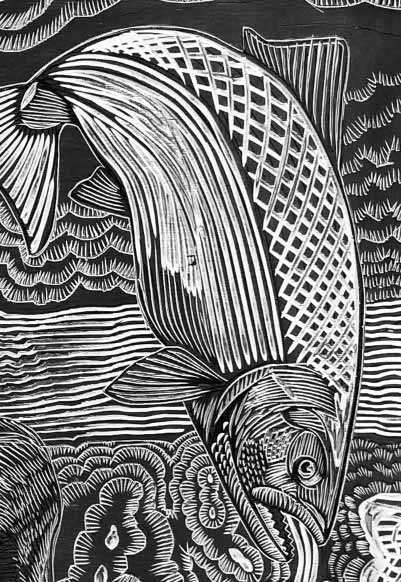

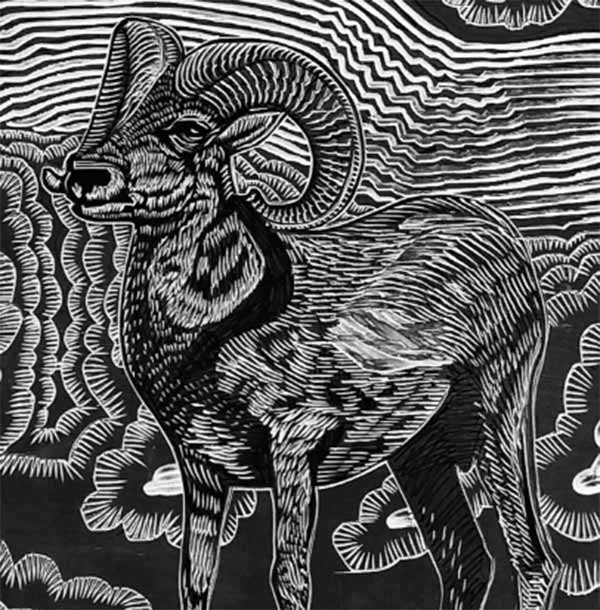

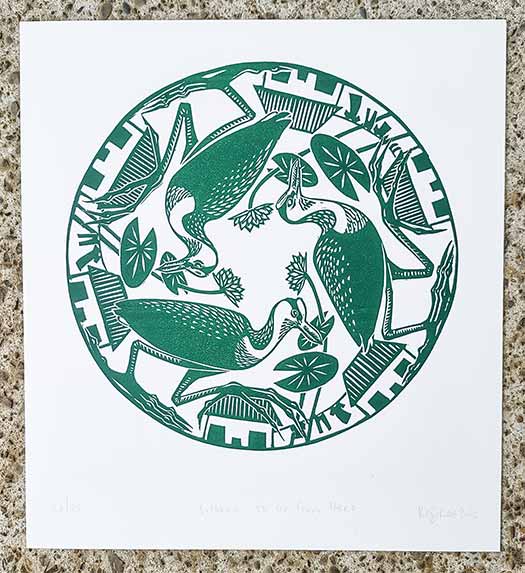

I picked four animals to mix into a map of my river section- a fish, an insect, a mammal, and a bird.

The Chinook Salmon, named for the Indigenous peoples of the region who speak Chinookan languages, is the largest of the Pacific salmon species. Much prized for its rich flesh and massive runs, the chinook population in the Columbia river has been harshly affected by the dams, fluctuating wildly and dipping to dangerously low levels. Chinook remain one of the most important fish species for Indigenous peoples in the region.

The Columbia River Tiger Beetle is a species of voracious arthropod predator, part of a great global family that tends to inhabit sandy places and hunt other insects with a combination of huge jaws and incredible speed. The Columbia River species was once widespread in the basin, but as the dams have brought up the water levels and drowned the sandbars they need to hunt, they’ve almost entirely disappeared and are now found only at a couple of sites on the Snake.

The Bighorn sheep is an iconic mammal of the Pacific Northwest and beyond, and you can still see them sometimes high above you as you drive the freeways through the Gorge. Their numbers are much diminished from historical highs, however, and populations are unstable and precarious.

The California Condor is the largest North American bird, and once perched on the basalt flows above the Gorge. They inhabited this area for tens of thousands of years, feeding on dead animals among the rocks below. Condors appeared in the basketry, beadwork, and stone art of the Columbia River Gorge region for thousands of years, until they vanished more than a century ago during the fury of settlement. Carcasses full of lead shot poisoned the birds until they vanished. The Condor survives thanks to captive breeding, but none are found here.

I finished carving the block and it will be printed on August 24th on a single 66 foot sheet of paper along with all the other blocks at the Maryhill museum. Read an interview with me that goes a bit further in depth about the process at Oregon Arts Watch .

Thank you for talking about your process- a beautiful piece of an amazing collaborative project. We will be there at Maryhill to watch the printing- so excited…

I’m so glad I found this article. It’s so well written, Roger! Section Seven is absolutely wonderful and so narrative. Thank you for bringing a fabulous vision to this project. You are a truly wonderful artist.

Lou