Eight Guantánamo survivors, in solidarity with the men who are still extralegally imprisoned there, have written an open letter (below) to President Biden calling for an end to a Trump-era policy preventing artwork from leaving the prison. The Trump administration banned the public release of artwork in 2017.

Khalid Qasim, who is still imprisoned at Guantánamo despite being cleared for release, recently said:

My greetings to you and to all the activists, lawyers, artists and everyone who works to spread justice and to close the Guantánamo prison. And from Guantánamo to the free people in the world, I ask you all to help me to free my artwork from Guantánamo. My artworks are part of me and my life. If the US government does not agree to release my artwork, I will refuse to leave Guantánamo without my artwork. The US Gov has destroyed my life, my paintings are the only part left of me. I appeal to you all to help me. Thank you very much.

The Guantánamo survivors are asking that people help them get their message out by sharing the letter and signing their letter in solidarity. Which you can do here.

The letter was organized by Guantánamo survivor Mansoor Adayfi with support from Remaking the Exceptional co-curators Amber Ginsburg and myself and in collaboration with Erin Thompson, Aliya Hussain and the Close Guantanamo Coalition. The solidarity signatures collected thus far reflect the connections between the military and police, and highlight the creative work of resistance movements locally and internationally. The letter has garnered solidarity signatures from long term Guantánamo activists Aliya Hussain (Center for Constitutional Rights), James Yee (former U.S. Army Muslim Chaplain at Guantanamo Bay), and Andy Worthington (Close Guantanamo), along with abolitionists Mariame Kaba (Project Nia) and Aislinn Pulley (Chicago Torture Justice Center). Additionally, prominent artists and writers such as Michael Rakowitz, Molly Crabapple, Laurence Ralph (author of The Torture Letters), and art critic Lori Waxman has signed.

Sign the letter in solidarity here.

To: President Joseph R. Biden, Jr.

The White House

1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW

Washington, DC 20500

From: Eight Former Guantánamo Prisoners (Mansoor Adayfi, Sabri Al-Qurashi, Ghaleb Al-Bihani, Moazzam Begg, Lakhdar Boumedien, Djamel Ameziane, Sami al-Haj, and Ahemd Erachidi)

Dear Mr. President,

Please end the Trump-era policy of preventing artwork from leaving Guantánamo and release the captive art from the prison.

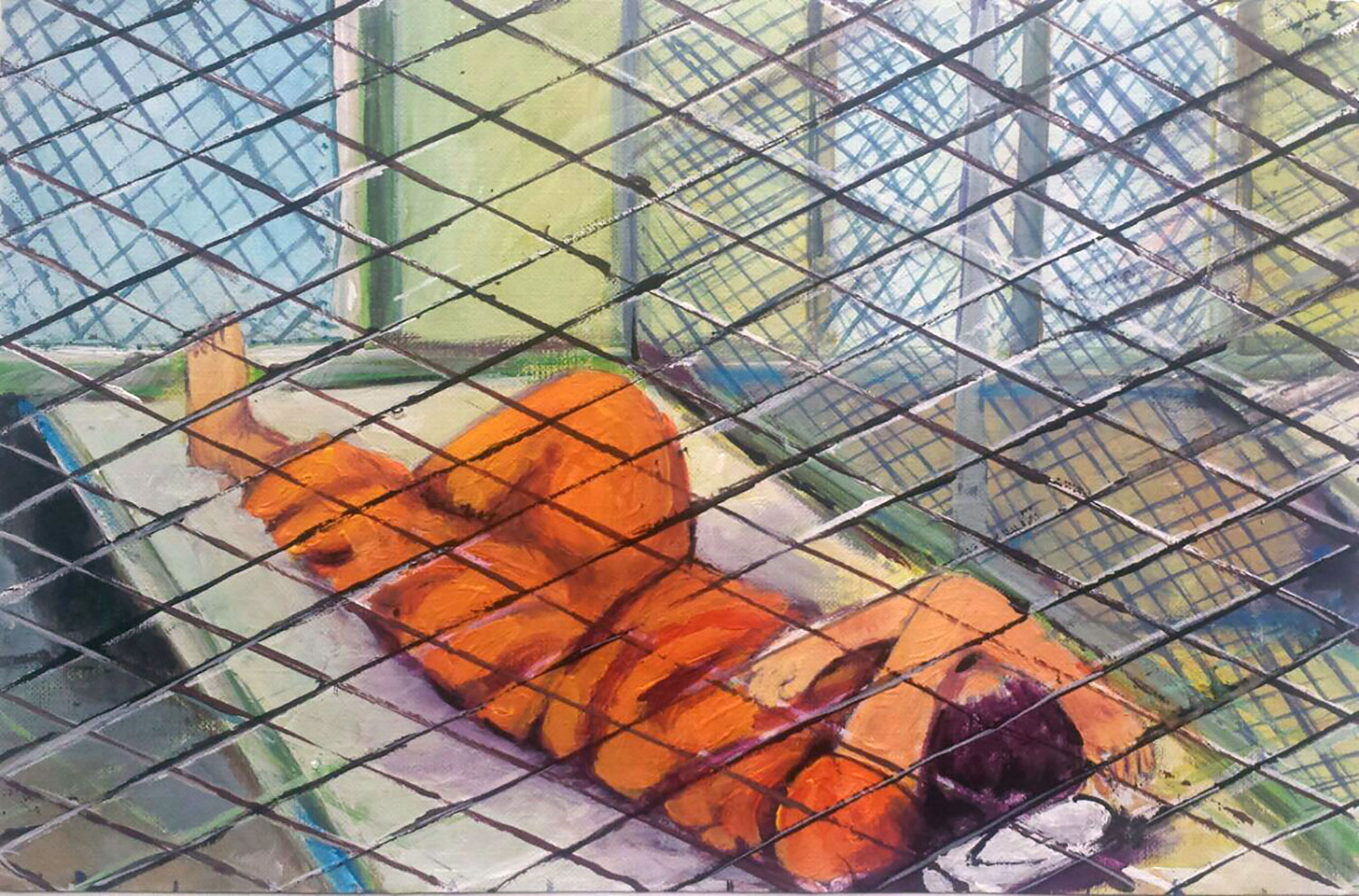

Arriving at Guantánamo was like entering a state between life and death. We were completely isolated from the rest of the world and became numbers in orange jumpsuits, caged 24/7. We spent years and years in those cages, unable to see life beyond those walls. Torture, hunger strikes, and isolation brought us closer to death and defined our imprisonment. The longer we stayed, the more we lost our sanity and ourselves.

In 2010, as part of a general improvement in living conditions when Obama failed to fulfill his promise to close the military prison, and as part of our negotiations with the camp administration, we were given access to an art class.

For the first time, making art was no longer banned.

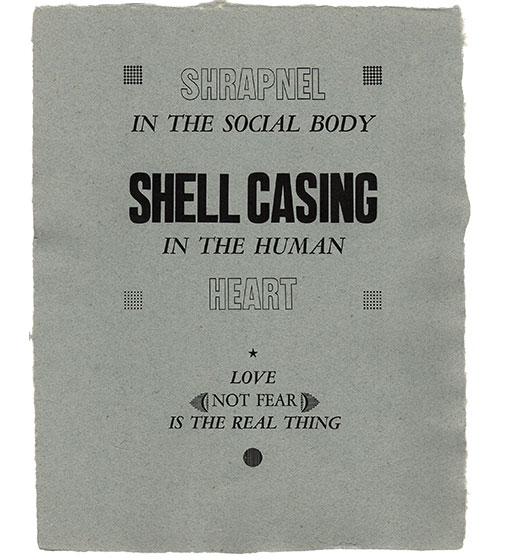

From the very beginning, we made art. We had nothing, so we made art out of nothing. We drew with tea powder on toilet paper. We painted our walls with soap and carved Styrofoam cups and food containers. We sang, danced, recited poetry, and composed songs. But because of this change in rules, we now had real paper, pens, and paints—colors we hadn’t seen for years. No longer did we have to hide our writings, paintings, poems, and songs—which had meant hiding parts of ourselves. No longer were we punished for painting or singing. We could reveal parts of ourselves that were missing.

You have to understand that what we got wasn’t just paper, pens, and paints. These were our tools to connect to our memories, to our previous lives, to nature, to the world, to our families. Art was our way to heal ourselves, to escape the feeling of being imprisoned and free ourselves, just for a little while. We made the sea, trees, the beautiful blue sky, and ships. We painted our hope, fear, dreams, and our freedom. Our art helped us survive.

And we shared our artwork. Artworks moved from one block to another in Camp 6, so we could all see each other’s work. We gave art to our lawyers and families as well as to guards and camp staff. Even the camp administration created a gallery to display our art to visitors, journalists, and delegations. We started to share our artwork with the world. Then, in 2017, after an exhibition in New York City, things changed.

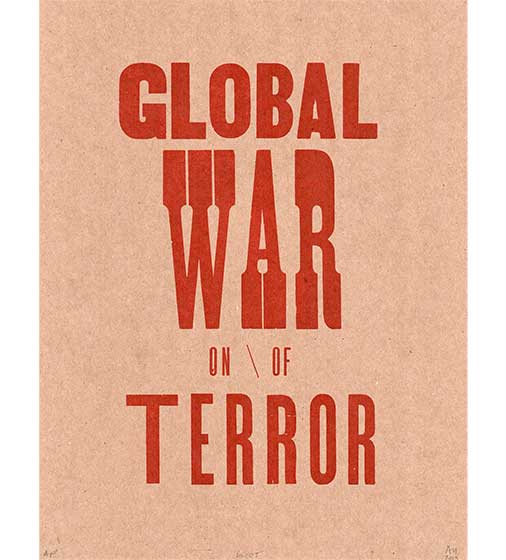

We wanted everyone to see this art, see its beauty. We wanted them to see how we used our artwork to fight injustice. But this message and increased public attention on the prison angered the Trump administration, which responded by banning anymore art from leaving Guantánamo.

Please, Mr. President—don’t follow Trump’s lead.

This art belongs to the artists. Its importance to them cannot be overstated. Moath Al-Alwi, who was cleared for release in January 2022, told his lawyer that he would rather his artwork be released than himself, “because as far as I am concerned, I’m done, my life and my dreams are shattered. But if my artwork is released, it will be the sole witness for posterity.” Khaled Qasim, who was cleared for release in July 2022, asked his brother in a call on August 3, 2022 to spread a message to the free people of the world: “I ask you all to help me to free my artwork from Guantánamo. My artworks are part of me and my life. If the US government does not agree to release my artwork, I will refuse to leave Guantánamo without my artwork.”

Art from Guantánamo became part of our lives and of who we are. It was born from the ordeal we lived through. Each painting holds moments of our lives, secrets, tears, pain, and hope. Our artworks are parts of ourselves. We are still not free while parts of us are still imprisoned at Guantánamo.

Mr. President, end this Trump-era policy and free the artwork from Guantánamo.

Sincerely,

Mansoor Adayfi

Sabri Al-Qurashi

Ghaleb Al-Bihani

Moazzam Begg

Lakhdar Boumedien

Djamel Ameziane

Sami al-Hajj

Ahmed Errachidi

Add you signature in solidarity here.

Our government does atrocious things to people all over the world. These things are not secrets to the victims, bystanders, survivors, et al. But our government tries desperately to keep the truth, not from our putative enemies, but from our own people, even Congress. Why? Because our government wants to continue the atrocities without having to face the needed and rightful, just opposition from decent people right here in our country, which could spell the end of these atrocities.

This is evil and highly undemocratic. It flies in the face of the principles that we hold up to ourselves and others. When shall we mend our evil ways? Start now. Better late than never.

The art reveals the humanity of the prisoners, the horrors visited upon them, and their kinship to us who are not caged. Thus, the government which continues to confine ‘the worst of the worst,’ feels threatened by its own lies and betrayals. And Guantanamo must forever try to hide its crimes.