Our ninth Dispatch finds us in discussion with Katya Gritseva, an exceptionally skilled illustrator, political artist, and socialist activist who lives in Lviv, Ukraine.

The fine folks at ESSF have also translated this interview into French here.

You can find all of our previous Dispatches here.

Will you tell us a little about yourself? Who are you? Where do you live now? And I think you have been displaced- so where have you lived over the past year?

I was born into a family of metallurgical plant workers from Mariupol. My family remains in the occupied territory, although our house burned down in the first days of the war. For the last five years, I lived and studied in Kharkiv as a book illustrator. But when the war began, going home to the Donbas was even more dangerous than staying in Kharkiv and I had to move to Lviv with other students. We used to live together in a dorm of the Lviv art academy and we were lucky that the administration of the Lviv academy allowed us to live in there. But a few months later, we were all evicted literally in a day and needed more time to find money to afford to stay there. The housing market in western Ukraine has become very cruel, because landlords demand exorbitant prices. I decided to stay in Lviv with my comrade and partner. Now, together with him, we are starting to revive the left-wing student trade union Пряма дія (Direct Action). In short, I can say about myself that I am a graphic artist, a poet, a socialist, a student activist, and a risky woman.

It’s impressive that you’ve kept up making art throughout the war and occupation. I can’t imagine how difficult that is. How have you made time, space, and psychic attention for creating art?

The war mobilized me and accelerated all processes: social, emotional, and intellectual. Now I work and study more than ever before. I’m afraid I won’t be able to do anything. I want to help the Ukrainian resistance and the revolutionary movement with what I am capable of – art! I have challenging days, and dangerous mental states have become more frequent, but everything happens so fast that I do not have time to drag out my depressive periods. It helps a lot that next to me, there is a team of my comrades and a common goal. The left movement in Lviv has grown more substantial, and I have met more talented, like-minded people. I don’t plan my week, I don’t try to be efficient, I don’t chase money. I draw and do politics because it makes no sense for me to live without it, and it’s also fascinating.

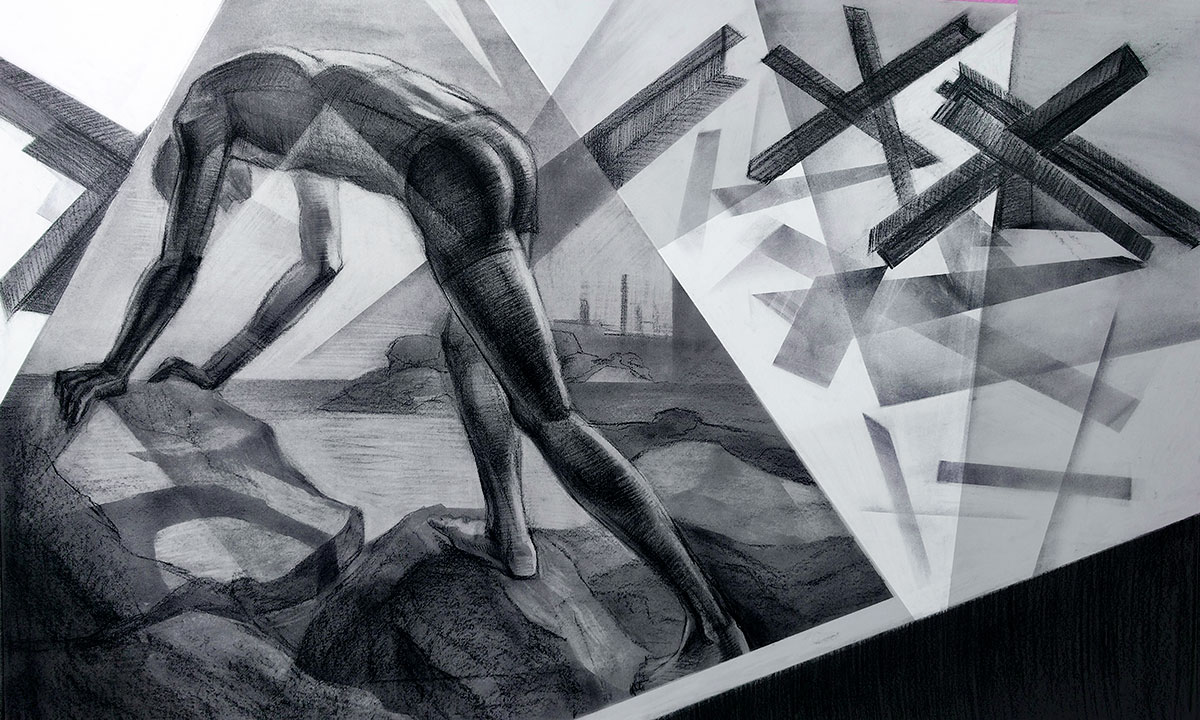

“The sea. Caution!’ charcoal drawing is epic, particularly your use of light and form. The similar form of the body and the tank-traps, and also the fragility and strength of the human body in the time of war. Will you talk about this drawing, what it was made for and how you approached it?

I did the work “The sea. Caution!” for the academy. Perhaps that is why it is different from my other work and is made in the academic style characteristic of the Kharkiv school, such as a dynamic charcoal drawing in the traditions of Soviet realist graphics. I worked on the concept for quite a long time, so this work is technical and expresses my important emotions about what happened in Mariupol. I can communicate with my family via the Internet, so I understand how difficult it is for them to adapt to new living conditions in a destroyed, occupied, city. In Mariupol, danger awaits at every turn. You can die from a bullet from the Russian military, hunger and disease, find yourself under the rubble of a house, and crime and violence are growing exponentially. My grandfather went out for a walk, and a burnt tree crushed him to death, on an ordinary sunny day, without bombs and shooting. The new reality is absurd. It’s revolting!

The picture shows my 14-year-old brother. I used his photograph to create the composition when we were at sea, and he was fooling around on the stones. Children and teenagers are forced to adapt, and they spend childhood in the realities of anti-tank hedgehogs and mined fields. They matured very quickly. If they did not treat their new life as a game, it would be more difficult for them to maintain mental health. Children swim in the sea, play on the playgrounds, and play ‘war games’. I can understand this situation, and at the same time it frightens and surprises me a lot.

How did you get involved in political graphics?

When I was faced with choosing what profession to choose after school, my political beliefs seriously changed my life path. I thought that I drew pretty well and maybe could design left-wing magazines, so I went to study book graphics. Now I create designs and draw for the organization of the Sotsialniy rukh and the Commons journal, and periodically I hold workshops on political topics. I am involved in political action almost as much as in art. It helps to navigate and complete graphic tasks with knowledge of all the features of activist work.

What do you want your posters to do? Educate people? Inspire them? Mobilize them? How?

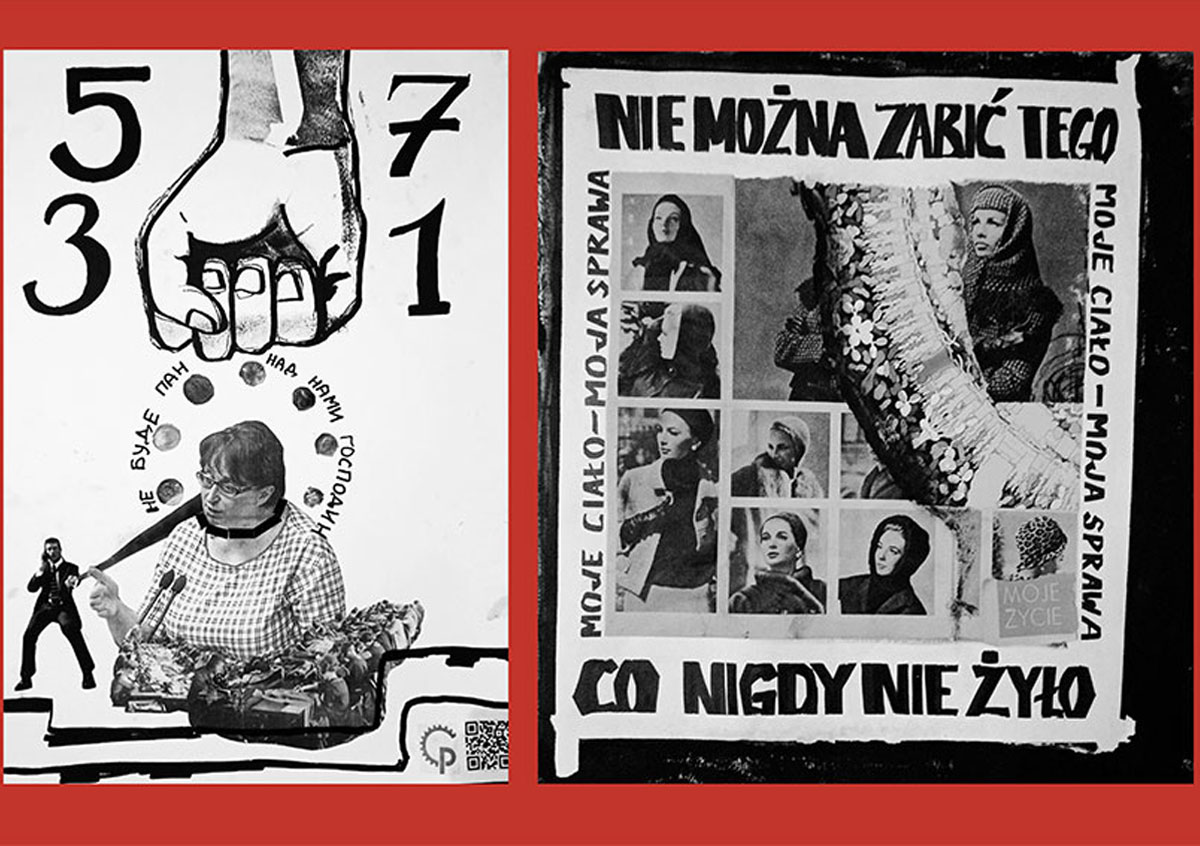

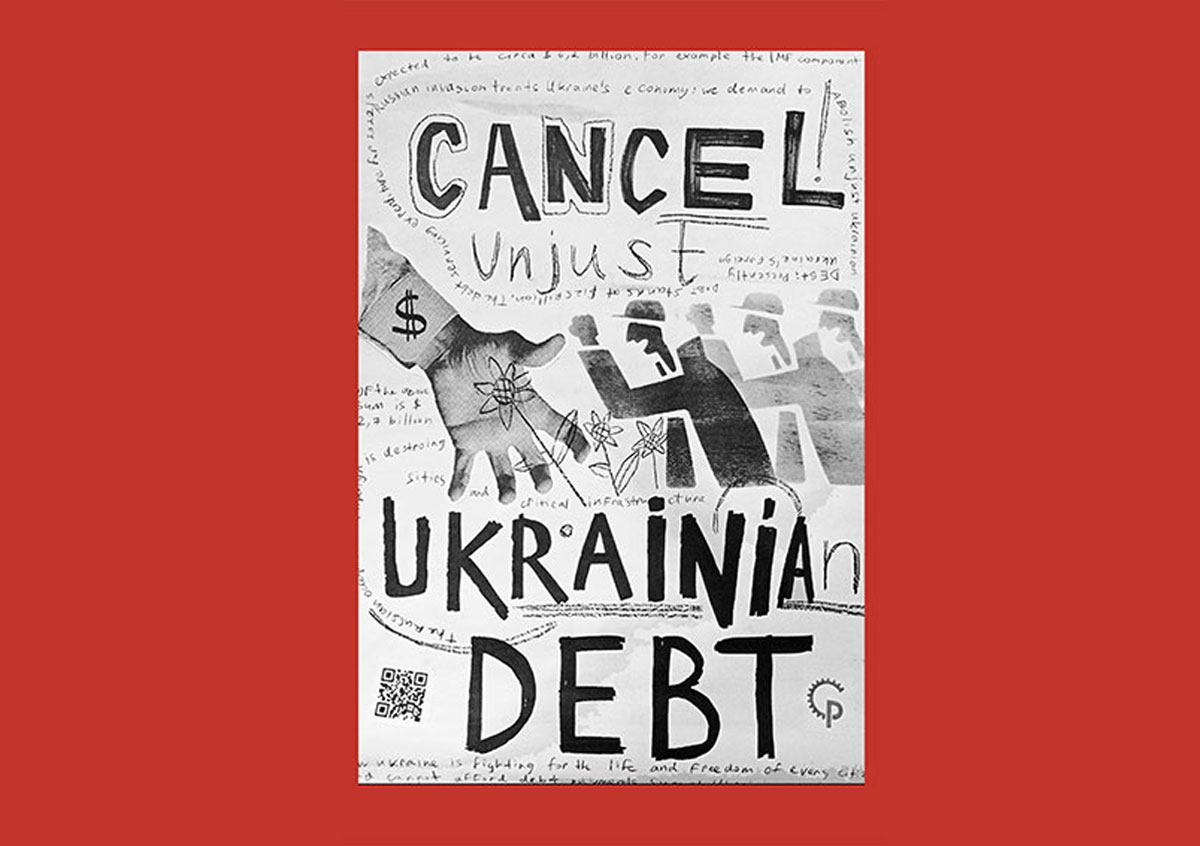

All of the above! I want to talk to more people about the socialists of Ukraine and involve them in political work. It’s cool if they realize their rights and opportunities and start to do something for others. Usually, I discuss the topics of posters with my comrades, so their semantic content is not only my merit. We publish posters in our media and allow friendly organizations abroad to freely use them for different projects.

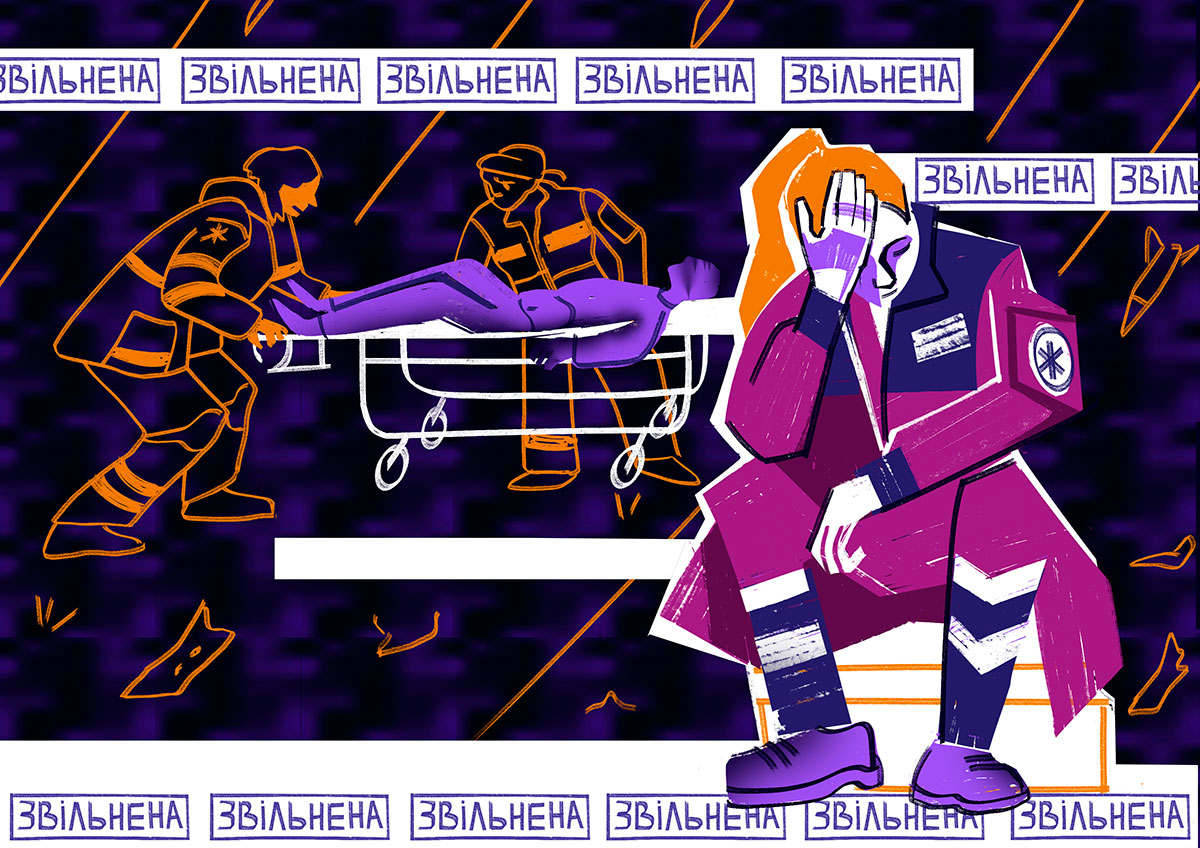

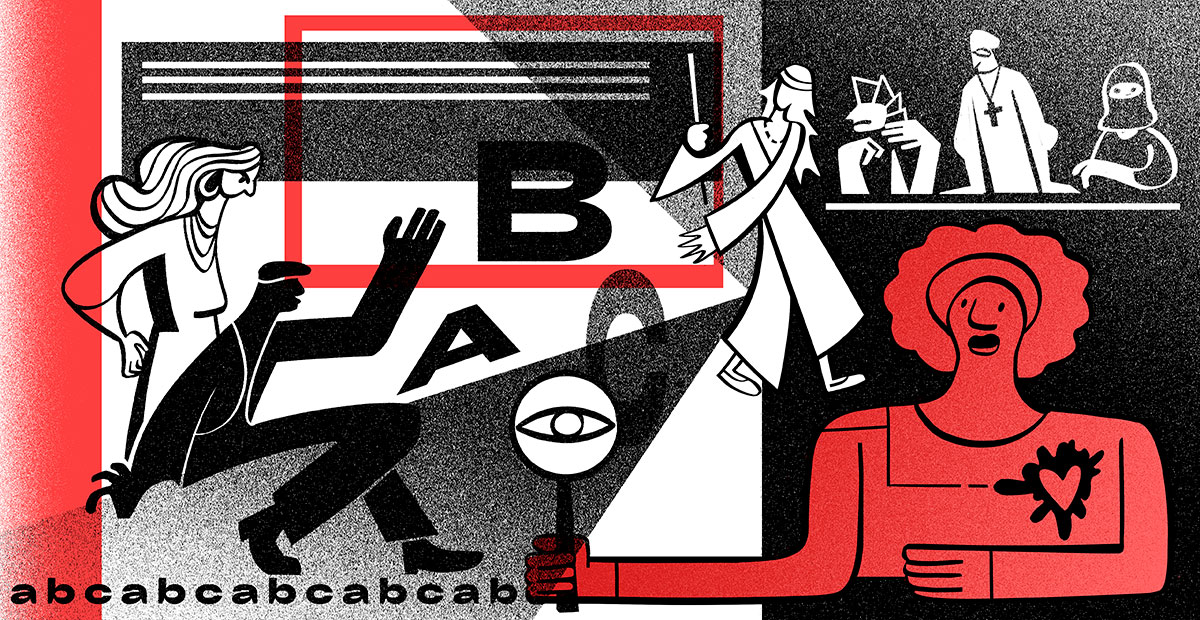

How did you approach your illustrations that you did for the Commons journal “After the war”? What was the inspiration? What drove the design? What did it take to visualize this idea?

For the “After the war” project, I had to figure out how to portray Ukraine, and if its development after the end of the war took place under the banner of progressive ideas. This bright futuristic work depicts people of various professions: doctors, teachers, builders, activists, artists, and so on. They all do something together and help others, creating the Ukraine of the future. I came up with the composition quite quickly, it is decorative and calls back to murals and sci-fi books. I would like to try to paint this picture on a wall in the future. It also seems to me that the picture for “After the War” is largely about Kharkiv, I put some associations about this city in it, including colors, and architectural elements. The authors who responded to the open call “After the war” tell about various topics. Their forecasts and analytics are often not as sunny as in my image. Ukraine is suffering from years of unemployment, the curtailment of workers’ rights, and poor infrastructure. I am very afraid of a right turn in politics. But the worst is to lose the war and end up in Russian slavery. The occupation did not bring anything good to my family, there is no need to have illusions about a good Russian empire. It is very important to find freedom and a place for left-wing politics in Ukraine now, and my picture is like an inspiring roadmap. This is an alternative that can only be approached if the left forces come to power.

Will you tell us about your work with Соціальний рух (Social movement)? Tell us more about your politics and how it affects your work. What is important for you to convey in your artwork?

I have been working in the Соціальний рух (Social movement) as a volunteer for almost a year. My activity is not only in designing visual materials but I am involved in the work of the organization itself. I helped organize SR groups in Kharkiv and Lviv, interface with the student movement, and participate in actions. For example, I organized an anti-fascist picket in Mariupol in 2021 and helped students organize a protest against the closure of the University of Architecture and Building in Kharkiv. We are a small organization, so the opinion of its ordinary members is taken into account in the formation of our policy if they are active. We identify ourselves as democratic socialists and advocate support for grassroots labor movements and popular initiatives, the fight against the patriarchal model of society, climate change, and discrimination against minorities. You can read more about the current position of the Social Movement in the resolution that we adopted in September 2022.

The organization in many ways shaped me into the way I am now, it helped me find contacts with like-minded people, and helped me find work regularly. If I didn’t have practical activist experience, I wouldn’t understand many things, I wouldn’t be able to portray them, and I would have less motivation. I quickly get feedback from people with similar views and clearly understand where I need to move and that I am going in the right direction. I separate my political designs from art that I make for myself–their purpose is completely different. It’s important to make bright and understandable works that make clear what is the meaning of this or that article, sticker, or poster. Simplicity and sometimes banality is not awful for this kind of activity (although it is difficult for me to make clickbait and banalities, I have to step over myself). I understand that sometimes you need to give up your strangeness to make a more democratic visual.

Did you organize some poster making workshops with Social movement? If so, will you tell us about that? What kind of posters did people make?

So far, I have held only three workshops. All of them were my initiative and aimed at a particular audience each time. Usually, I prepare a small study on the topic (posters, stencils, prints on cardboard in political art). After a short lecture, we proceed to the practical part. I use cheap materials and materials which we can find at home and teach people how to use recycled materials to prepare paintings. Even before the war, we had limited resources, my family lived poorly, and I was used to not spending money on expensive art materials. Many people have now had to move. They cannot store materials and art in their temporary homes, printing presses are too expensive, prices for essential items are rising very quickly, so spending money on elegant paper is the last thing. It is important to show people that their economic situation does not prevent them from being artists. Perhaps this is the main idea I want to convey in my classes. In general, I observe a trend in Ukraine, which manifests itself in the normalization of freeganism, the processing of used materials, and more people organizing into cooperatives.

An example is the DIY culture festival in Lviv, which recently attracted many young people. The Gareleya Neotodryosh project, which brings together artists from the eastern region of Ukraine, also shares similar ideas. Often the curator Vitaly Matukhno holds exhibitions in abandoned buildings and buildings not intended for art exhibitions. It is difficult for aspiring artists to break into gallery spaces if they are private, so this is a good initiative, which shows that it is not at all shameful to be an “unsuccessful” and not-rich artist. You can be content with little.

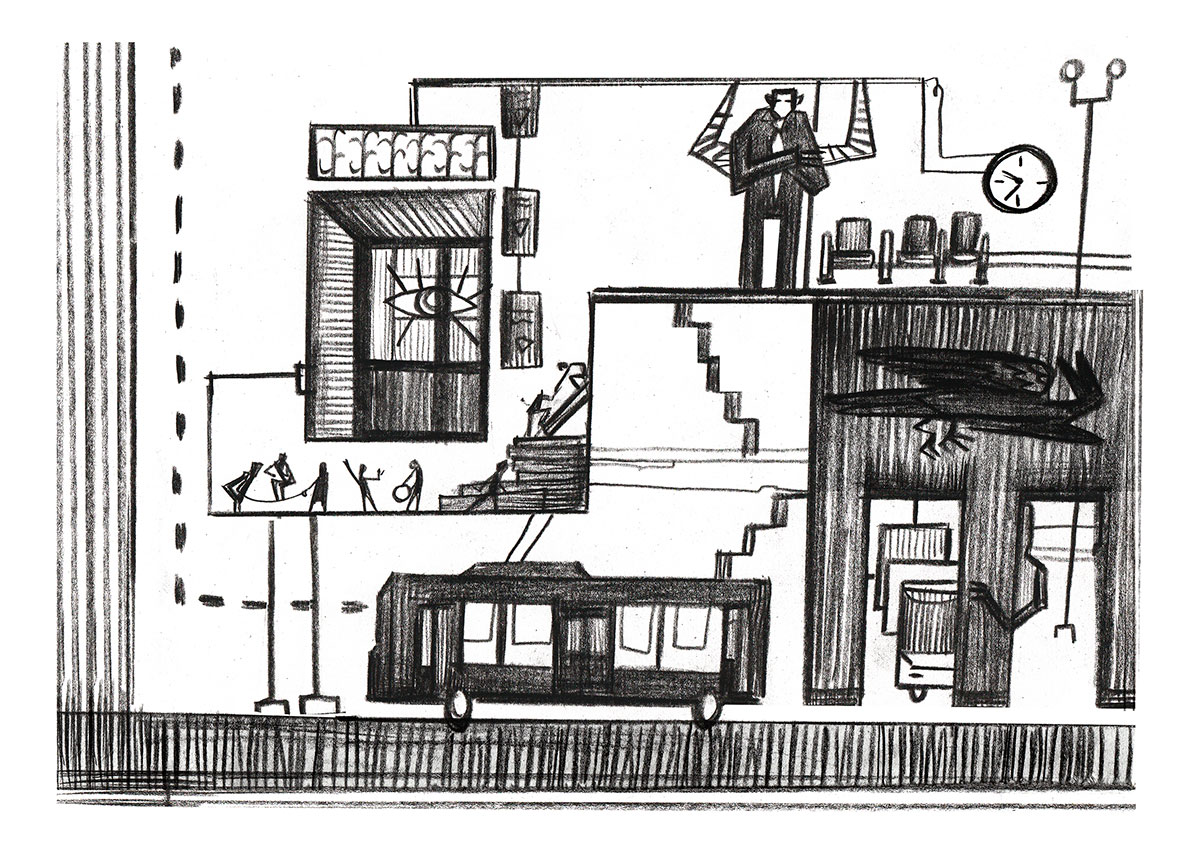

You create images that often highlight people’s connection to work and industry, and your illustrations often use sharp and stylized line work depicting people and places. These seem to me to be deliberately drawing on a Soviet/socialist graphic and political heritage. I’m curious about how this sits contextually in the present moment.

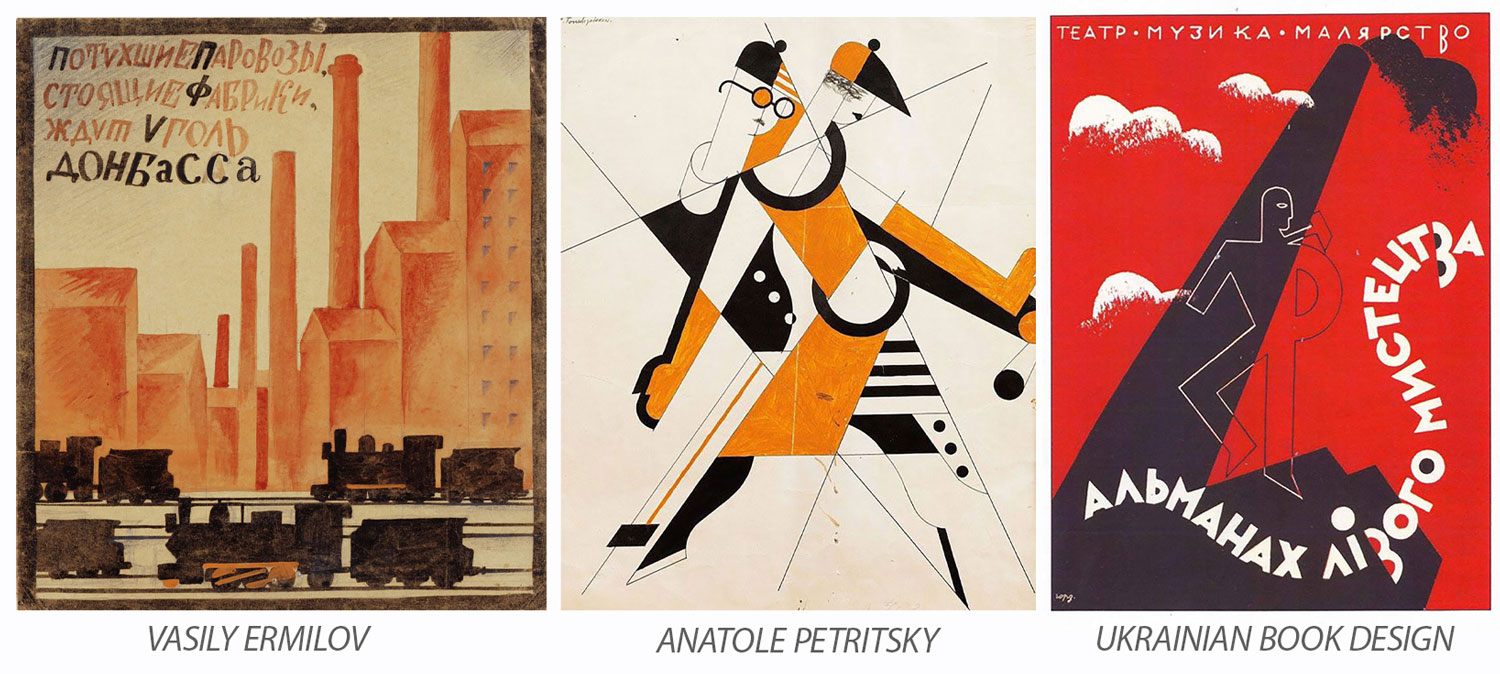

I was strongly influenced by the observation of Soviet monumental art, which we can find in all Ukrainian cities. In Mariupol, mosaics and murals looked interesting, and there was a period when I was copying these things. Ukrainians do not perceive the rethinking of the Soviet style as something terrible. We even have youth movements defending Soviet cultural heritage (Save Kvity of Ukraine). In essence, this is our history and our people, Ukrainians once created all these graphic, monumental, and architectural works. Of course, haters of this approach advocate the destruction of the cultural heritage of Soviet Ukraine and criticize the old and new left. Someone likes my style, someone doesn’t–I can accept it, and I’m not going to go at it with my class and ideological enemies. I cannot say that I deliberately draw parallels between Soviet militant left art and what is happening now in Ukraine. I like modernism. I was influenced by the Bauhaus and Kharkiv avant-garde artists who surrounded me in my context. I find the roots of my style even in Soviet cartoons. It’s just how I was formed.

In one of your IG stories you ask the questions, ‘Is there a history of militant left art in the Ukraine?’ What is your conclusion?

I asked the question jokingly because I had to create a funny inscription on my photo with a gun from the Science Museum in Lutsk. But some people took my question seriously, so I also thought about it and did a little research. The avant-garde art of the beginning of the 20th century fits this term most successfully. Artists from Ukraine strongly influenced the development of such styles as cubism, futurism, and abstractionism. The radical artists of Kharkiv did not shy away from engaging in propaganda graphics and, at the same time, made many technical experiments that went down in history. Some well-known artists are Vasily Ermilov, Adolf Strakhov, and Anatole Petritsky. There are few contemporary openly left-wing artists in Ukraine, but they exist. Among them are Nikita Kadan, David Chichkan, and the group Воїни добра і світла.

What artists inspire you? Are there other Ukrainian artists that you work with, appreciate, or think we should know about?

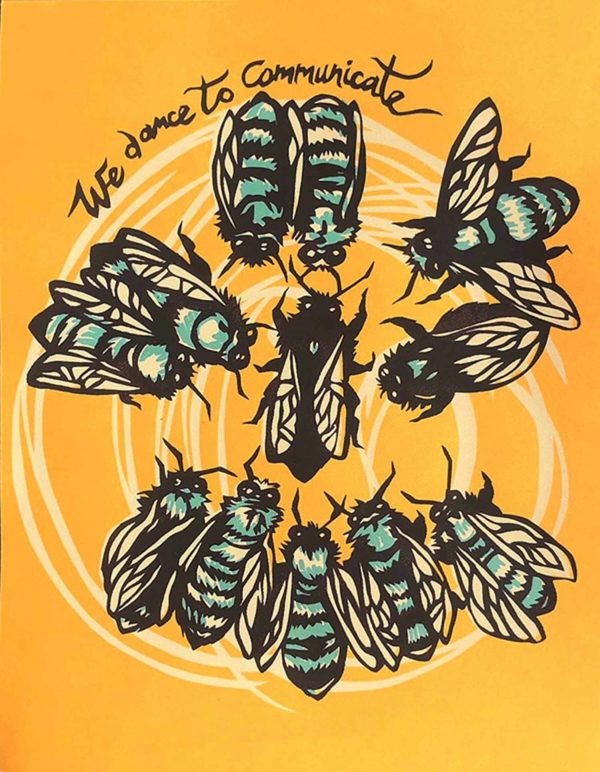

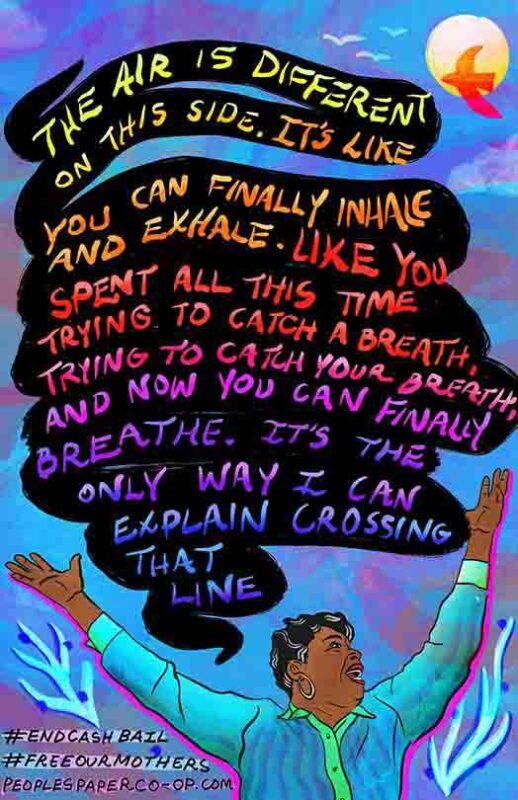

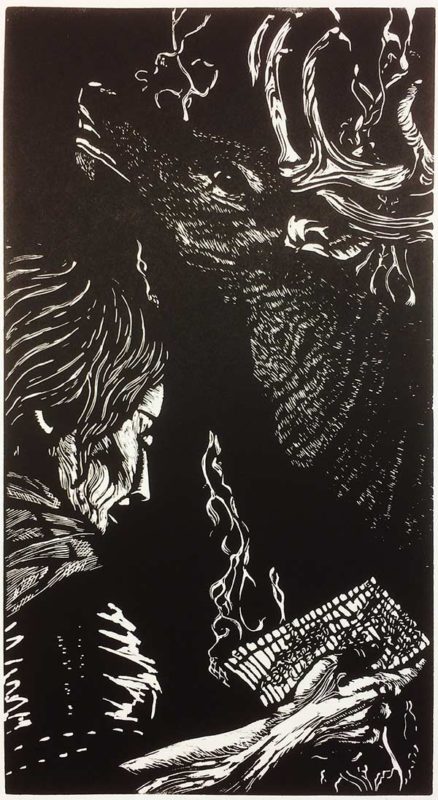

I don’t like oil painting, so my most influential authors are graphics. Significant authors for me are Frans Masereel, Rockwell Kent, Käthe Kollwitz, and Aleksandr Deineka. Of contemporary artists, I love the author of comics and political posters, Michael de Forge. Different areas of art influence each other. I am very attentive to photography and cinema, so I would like to highlight filmmakers such as Chris Marker and Michelangelo Antonioni in addition. I try not to fall out of Ukraine’s context and art scene. I participate in residencies, go to lectures and communicate with artists. I am close to the work of groups such as Studio Serigraph, Etching Room and Lithography30. I meet many nice people, and I highly appreciate the artworks of my friends Dasha Molokoedova, Sonya Bylym, Denys Pankratov, Karina Sinitsa, Olga Lisovskaya and photographers from the Truba group Olexiy Chistotin and Ihor Chogol.

How can people find your art? How can people support you?

As soon as the war began, my artistic work spread through the global network and left-wing publications. A lot of effort was put into this by the French publishing house Syllepse, whose editor I met through connections from the Social Movement. I’m a little irresponsible about my copyrights, and I wouldn’t say I like the concept that art can be appropriated only if you are the author of the picture. So far, this position has only helped me. For example, activists were able to hold exhibitions with the participation of my work in Paris, Belgium, Germany, Italy and Japan. Although this did not bring me material resources, it nevertheless helped me become more connected and showed people abroad that Ukrainian art can carry specific leftist narratives.

You can find me on social networks (IG: cmrd_grits, Facebook, and Behance), support with a repost or financially. If you want to hold an exhibition in your city, I can provide works for free. I am open to any suggestions and collaborations. Since my family suffered in Mariupol, I decided to sell stickers and postcards about this city for donations to support them. So I can send you files to print these materials.

Are you working on any projects right now that you are excited about and want to share?

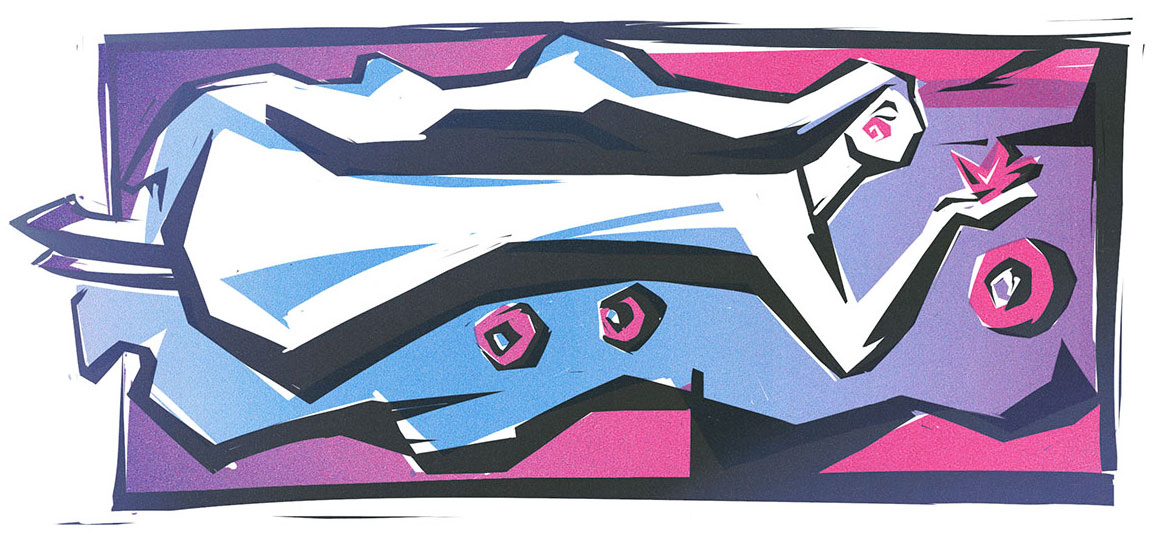

I am working on a book about personalities from the history of the Ukrainian left movement with my friend Vladislav Starodubtsev. I will do its graphic part. This project is still only a draft, so I can not share materials about it. Also, I made illustrations and layouts for Saul Alinsky’s book Rules for the Radicals this summer [pictured above]. I did all the technical parts, and my comrades from the social movement did the collective translation into Ukrainian. The book contains six color illustrations, which I then divided into 15 small ones and used in the book block.

Music and audio are a big part of my art-making experience. What, if anything, are you listening to while making images?

It isn’t easy to do only one thing when I work, so music or audio lectures help me focus and maintain interest. I like to find musical rarities and make themed playlists. I am especially interested in electronic music of the 80s and new wave. I am a nervous and twitchy person who draws quickly and passionately. Therefore, most often, the music that I like is the same. Now I usually listen to Grauzone, Aksak Maboul, Sleaford Mods, Easter, Svitlana Nianio and the early albums of Skryabin (Мова риб). Of modern Ukrainian bands, I like Kurs Valut, The last passenger, Yuriy Bondarchuk.

Anything else you want us to know?

It is important to understand that Ukraines struggle is resistance to an imperialist and extremely totalitarian system, not in defence of the official government and its idiotic anti-labour laws. This is a battle for the right to the independent existence of such territory as Ukraine and the freedom of its people. Russian nationalism and oligarchic power are a much bigger problem than Ukraine’s weak right-wing radicals, don’t buy into Russian propaganda. Genuine socialists can’t conduct political activities in the occupied territories. If you want to help the Ukrainian people, don’t be idealistic, analyze current events, and don’t live by dogma. Demand sufficient weapons for Ukraine and a visa-free regime for refugees of any countries that suffer from imperialist wars in your states.

You can also support local horizontal organizations such as Sotsialniy rukh, Solidarity Collectives, and Ukrainian feminist groups. If the position of these NGOs does not suit you, then help the Ukrainian trade unions or take part in humanitarian aid to the victims of the war. Ukrainian culture has long been dependent on Russia in the east and Poland in the west, so spreading knowledge about the work of our artists, writers, and musicians will be of great help. We have the right to subjectivity and need to be visible and free from colonial stereotypes.

Interview conducted via email in November, 2022.

Signal: A Journal of International Political Graphics & Culture is the collective project of Josh MacPhee and Alec Dunn. All copies of Signal are available for sale here on Justseeds.

Hello. Very interesting interview. I am a poet, translator and activist. I am original from Chile, a former political prisoner ( 1985). I left Chile in 1990. Now I live in Australia.

In solidarity

Juan