By Manon Thompson

Last fall I met Meredith Stern at the Uri-Eichen Gallery in Chicago, during the opening of Chip Thomas’ exhibition, Be here now! She wore a vegan pleather jacket and tall black boots, and embodied my idea of strength and commitment to women’s rights and universal human rights.

In conversation, Meredith mentioned her new coloring book and her goal to distribute the books to the younger generation to help them learn about the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We also talked about other projects, including her joining a new band.

I was honored to interact with Meredith, and I wanted to follow up with her about her inspirations, trajectory, and belief in art.

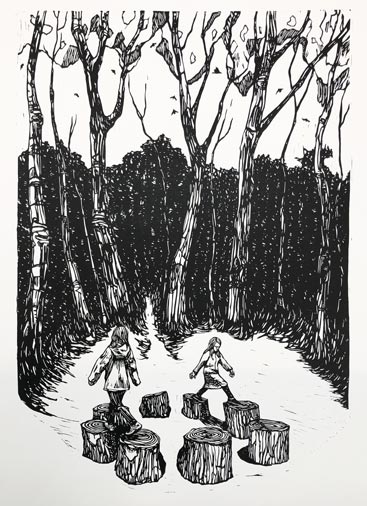

Meredith Stern is one of the founding Justseeds members. She was raised in a small Pennsylvania town, but obtained her BFA in ceramics at Tulane University in New Orleans. She lives in Providence, Rhode Island where she currently is a drummer and has a versatile art practice involving printmaking, zine publishing, ceramics, collaging, and gardening.

My name is Manon Thompson. Last fall, I was in a class about movement graphics and was inspired by the artworks and artists we worked with in the class including Meredith Stern.

I reached out to interview Meredith about what it is to be a socially engaged artist and the narratives that an artist creates about themselves, and the world around them. Understanding an artist’s story has helped me get to the heart of their art practice. I hope it does the same for you.

The following interview was conducted in the fall of 2019.

Manon Thompson (MT): After thinking about your zines for This is an Emergency, specifically the one about a woman’s day getting an abortion, what does a day in the life of Meredith Stern look like? Could you take us step by step, through an average day for you, similar to the zine’s narrative?

Meredith Stern (MS): Today, I woke up, drank coffee, and reprinted six images for the Justseeds website.

I’ll unload my recent ceramic work from my kiln after lunch. The items in my kiln are a combination of ceramic olive oil containers I’ll be selling at holiday sales, as well as some mugs and kitchen items.

I’ll pick up our kid at 4pm, and we will likely run around the playground for an hour, then I’ll make dinner.

MT: With this in mind, how do you think narratives such as zines contribute to your visual work?

MS: The entirety of human history is the recounting of our values, histories, and beliefs through narrative–oral storytelling, visual depictions, and written accounts. I believe narratives are a powerful and successful way for humans to communicate with one another, to gather together, to share knowledge, to tell our histories, and to promote our visions of a just world. I see zines as one way to communicate directly, immediately, in a fairly accessible and low-cost medium. Zines are a great way to combine stories and images into one project that we can hold in our hands. Throughout the years I have often created zines when it seems like a useful way of telling a story.

MT: How does this illustrate what it is to be a movement graphics artist?

MS: I self-identify more as a socially engaged artist. To me, movement graphics is art specifically being used in a movement—a good example is Art Builds, which several Justseeds artists, specifically Nicolas Lampert and Paul Kjelland have been working on. That is when artists are being directed by the movement, to create graphics for protests, strikes, branding for a specific campaign, etc. The artist defers to the organizers in order to create graphics that the movement feels will best express the issues. It’s very unique in that instead of the traditional artist ego driving the piece, the movement is directing the visual art.

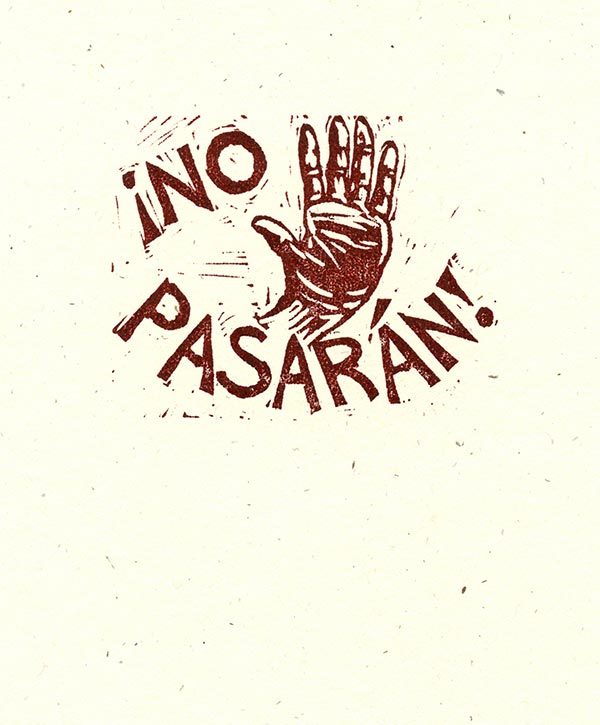

Occasionally, I work with an organization to create a graphic for their use, but most of the images that I create are self-generated. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights project is an example of this. When I created this project, I read dozens of articles by organizations working on these issues for language, imagery, etc.; but ultimately, I am not being directly accountable to a specific organization. So, I consider those graphics to be “socially engaged graphics” but not necessarily movement graphics.

MT: One of the projects, you touched on a bit was your creation of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. I would love to hear more about it. In your statement you say that, “We are not taught this document in most educational settings. It is activists and organizers such as Loretta Ross who teach and remind us about our rights and it is through grassroots organizing that we make institutions accountable to uphold these moral values.” With this in mind what actions have you taken in order to spread awareness of human rights through your art?

MS: My hope for these booklets is that they are utilized in educational settings as teaching tools. I donated twenty copies to the Providence Public Library to be in circulation here. I also have donated copies to teachers around the country. I recently spoke at my kid’s school with the 5thgrade class. They are learning about Human Rights. So I donated some booklets to the class and spoke to them about the project. The students will be creating their own images of articles of the document.

Justseeds member Aaron Hughes also utilized these booklets in work with the Prison and Neighborhood Arts Project. Folks who are currently incarcerated created visual representations of articles of the document. These are a couple ways that the project has been used so far. I hope more folks will find ways to amplify the document and further, to use a Human Rights framework in organizing work.

MT: Also, what went into the decision of visualizing each right? For example, why did you choose to portray the human rights article 15, “everyone has a right to nationality” as an image of two figures with their arms around each other with an inscription reading free Palestine?

MS: Before creating the booklets, I read dozens of articles on human rights issues in the US. They dealt with lots of versatile topics from different countries. My resources came from Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, ACLU, and the Southern Poverty Law Center.

I then tried to pair specific current Human Rights issues in the US with relevant articles in the document. Regarding Article 15, it shows an image of a Jewish and Palestinian kids arm in arm in struggle. My family is Jewish and escaped the pogroms of Eastern Europe and came to New York in the early 20thcentury. I grew up with the famous Martin Niemöller quote in our kitchen:

First, they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a socialist.Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a trade unionist.Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Jew.Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

In our household, we were raised to believe that injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We learned about the pogroms our Jewish family fled Europe to escape, and that we must fight for justice everywhere, for and with everyone who faces it. This includes fighting for the freedom and independence for Palestinian people, who are living under a system of apartheid and militarism under the state of Israel.

The slogan “free Palestine” is about liberation for Palestinians and their land from this violent military repression and occupation. They are being denied the right to have a nationality, and the United States government helps Israel, both financially but also through their recent declarations which increase violence and tensions in the region. Including the statement by Trump in 2017 that Jerusalem be considered the ‘capital’ of Israel, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared that Israeli settlements in the West Bank don’t violate International law.

So, Article 15 of the UDHR which is about the right to a nationality seemed very relevant to this issue.

MT: Meredith has currently been making art involving her ancestry. One of her new projects is World of my Mothers. In her description of the work she said that she was “going through the archival documents and photos of our family and trying to find out all I can about the Russian origins of my family. I discovered an envelope of pictures of Russian family members – some of whom survived the pogroms and World War 2 by living out the war years in the Ural Mountains.” It is interesting to see that socially engaged graphics can be spurred on by personal narratives such as ancestry.

Another project she has been working on is Cooperation cats; she makes mention of her child helping create one of the pieces called Intergenerational Strole, “The scribble lines were drawn by my four-year-old kid.” This is another example of Stern’s art incorporating her personal stories into social justice narratives.

I am looking forward to the further projects she creates which no doubt will help change the world.

Links and Resources:

- Human Rights Watch https://www.hrw.org/

- Amnesty International https://www.amnestyusa.org/

- ACLU https://action.aclu.org/

- Southern Poverty Law Center https://www.splcenter.org/

- Human Rights Watch report on Israel & Palestine: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/israel/palestine

Manon Thompson is an undergraduate student at University of Illinois at Chicago. She took part in the Museum & Exhibition Studies course Showcasing Movement Graphics taught by Justseeds member Aaron Hughes. During the course students took part in organizing, curating, and installing the Networks of Resistance show which included Meredith Stern’s work. This interview was originally conducted in 2019 as part of that course and was edited for publication in 2020.