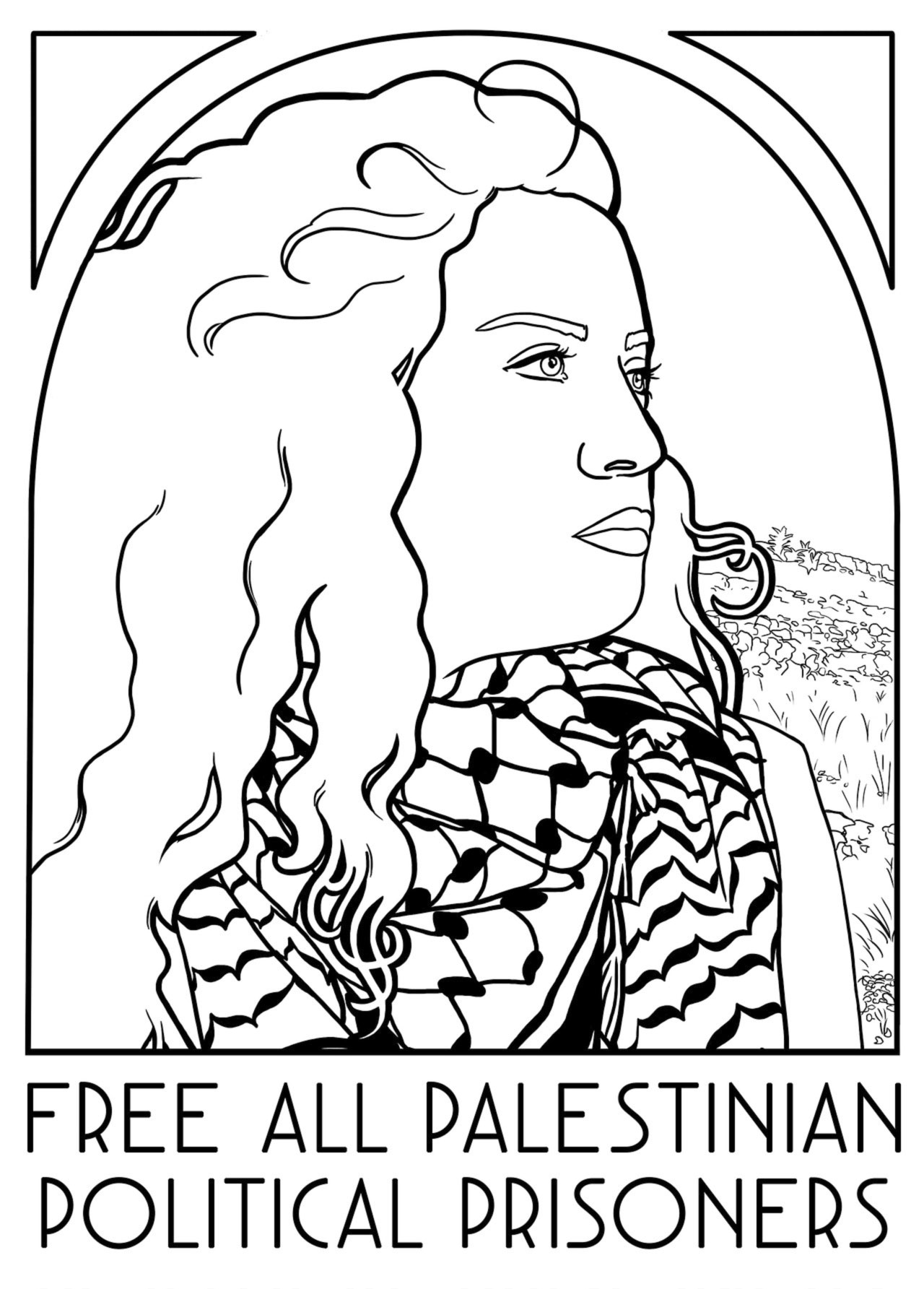

We’re very excited to welcome Zola into the Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative. Zola is based in Montreal/Tiohtià:ke, and over the past decade has become one of the city’s most prolific and recognizable street artists, with her unique wheatpasted cut-outs of people protesting, in struggle, and resisting authority. Zola is going to bring a whole new angle to art and politics here, and we can’t wait! As in introduction, here is a short interview conducted over email by Josh MacPhee in June 2020.

How did you get involved in art? Street art? When did that start to intersect with politics (or vice-versa)?

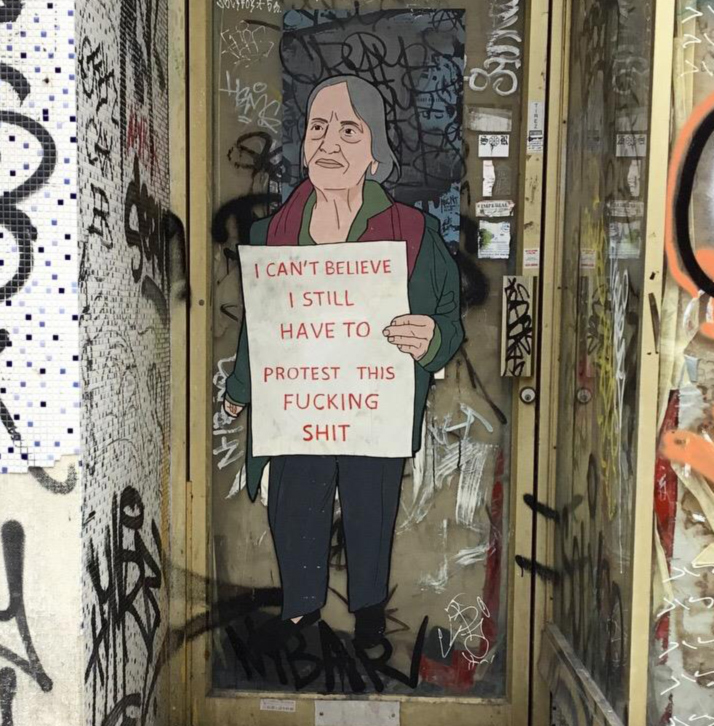

The first times I tried out street art, I was still living at my mom’s house. I don’t think I put much thought into it at the very beginning. I was only looking for something cool to do to emancipate myself while transitioning out of my teenage years. But pretty quickly I started putting political thought into it, as politics were starting to take up a bigger part of my life and identity. Art and social movements have ended up being inseparable for me over the past decade. When Occupy happened in 2011, I wanted to participate with street art, and I put out a call in local yarn shops to form a yarn bombing collective. We created this super rad feminist collective called Maille à Part (Mesh Apart), that lasted a good three years. We became good friends and worked in affinity and produced amazing discourse and created beautiful community artworks. I learned a lot from being in a political art collective in that time, and together we would think through issues we cared about and build positive spaces to push against systems of domination. When the collective disbanded, I wanted to keep doing street art, and moved to figurative work so I could be more explicit in the themes and messages I wanted to convey. That’s when I started wheatpasting under the moniker Zola.

Around that same time I got involved in a more typical organizer practices too, being part of a bunch of different projects and campaigns and putting together events, most often related to street art or with a street art component. So both my art practice and my political activism have fed each other organically in a way that is inseparable. It has always been a marginal space to hold. Most people are more rooted in either an art practice or a politics of struggle and few people really do both.

The majority of your work (that I’ve seen) are very realistic representations of people on the far left in struggle. Lots of masks, black bloc, fence cutting, and general images of embodied political transgression. What do these images mean to you? Is your intended audience people that are part of these movements, or the general public, or both? What do you want people to take away from coming across your work?

At first, I definitely wanted to speak to “the general public.” When I started the series of masked protesters, they were mostly all portraits from real events of the Montreal Student Strike that had just happened, or from other anti-capitalist demonstrations in town. I wanted to uplift the visibility of radical politics and also push for a realistic representation of the diversity of identities within black bloc tactics. I was very annoyed by the stereotypes upheld outside of—and also within—the anti-capitalist movement that black blocs were a bunch of skinny white guys in their twenties. That wasn’t what I had experienced so I wanted to speak out. My intended audience shifted as I got more of an online following and recognition from my peers. I realized my art was probably more enjoyable to them than the regular person on the street. I also started dealing with constant destruction of my most radical pieces in visible public spaces, which made me question the compatibility of the wheatpaste medium for a general audience. I often question myself on how to best reach a target audience with an appropriate or effective medium, and also uphold my passion and dedication for illegal street interventions. I am also not an artist by profession so I sometimes just accept the limitations of what I create.

In the US, the street art scene has become increasingly vapid and apolitical, largely used as a launchpad for gallery careers. Is this also true in Montreal, or are there a number of artists putting up work who are in dialog with the social movements in the city?

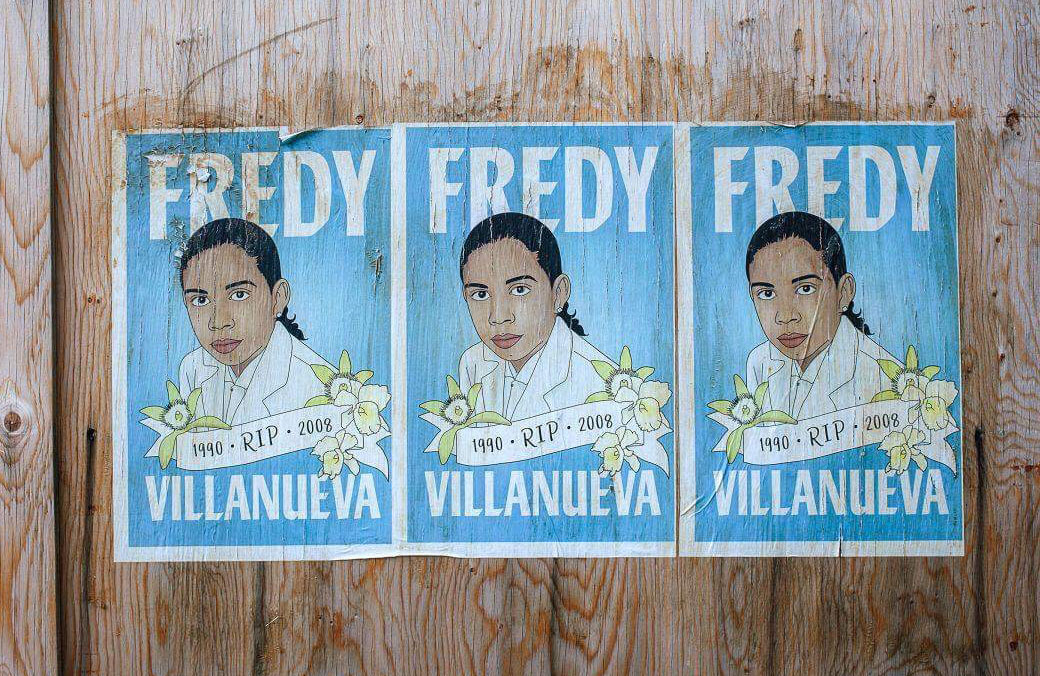

I think both are true to different extents. The general street art scene is definitely apolitical or even corporate. Most street, mural, and graffiti artists revolve around mainstream festivals like Mural Fest in the hopes of getting paid gigs and gallery shows. I don’t blame them, but I find the dynamic atrociously problematic and self-serving. I think the concept that “art in-and-of-itself serves community by being beautiful” is very broadly and uncritically accepted by most street artists. And then there are multiple people, affinity groups, and community groups who take up street art or some form of political vandalism to serve a wide array of social movements. I do stumble upon really cool stuff I had absolutely no knowledge of prior to, and can’t tell the author. That is the true power of street art, for anyone with any level of skills to take up a project and just put it out there, before any other social regulation or mediation process needs to happen. Those practices will be punctuated or disorganized, so they might be less visible on social media or recognized by the cultural world. While all these types of art interventions are found in the streets (alley productions, big murals, fundraiser show posters wheatpasted under an overpass, slogan graffiti, etc.), there is barely any overlap between the main street art scene and social movements except in a few cases like me. We almost all know each other, and friendships have come and gone.

Street art and graffiti are often thought of as being fairly solitary activities engaged in by individuals, who build communities around it online. But you have been involved in a lot of organizing with street artists in person in Montreal, esp. with women, BIPOC, and other folks not always thought of as part of the street art scene. How did that come about? What have the effects been?

The collective projects I was a part of that united street artists were in different social movement contexts and had different impacts—but all of them were aimed at raising the voices of the unheard or marginalized groups and identities. I mentioned above the feminist yarnbombing collective during the 2012 student strike. We had a few objectives: creating safer and accessible spaces to talk about politics and unwind from the street clashes with police by organizing stitch-n-bitch circles, connect the student strike issues with larger social groups and alliances with the elderly and women’s groups, identify the impact of patriarchy on dividing forms of art between high art and domestic craft, value and recognize women’s labor, and of course fill the streets with the symbol of the campaign, red squares. I think we were highly successful. We were all students and so we were also participating in our respective general assemblies. There was no disconnection between organizing forms withing the student movement and our structure as an art collective. It was social and political from A to Z.

I was also a co-organizer of a few off-festival campaigns against Mural Fest, trying to create solidarity between different street artists who were BIPOC and/or queer and/or women. In 2013, we put out a zine with critiques of the corporatization of street art and the lack of diversity of artists recognized within the scene. The zine is discontinued now but it exposed an important interest in these discussions. It created and made space for a critical discourse on street art that was very marginal.

I was also involved in the foundation and organization of the Decolonizing Street Art Convergence and helped during its follow-up Unceded Voices festivals in 2014, 2015, and 2017. These events happened at a crucial moment where Indigenous issues were being brought up more and more in the cultural and social mainstream spheres but there was no recognition of an anticolonial or antiracist presence in street art. DSA/Unceded Voices created that space. The most beautiful thing that came out of it from my point of view is the friendships and the connections that the participating artists created by meeting each other from across the continent.

You are right that nowadays, politicized artists spend most of their energy creating networks on social media platforms. It obviously has its strengths in building unified and diversified voices, connecting struggles, and gathering resources, etc. For example, DSA/Unceded Voices could not have happened if the main organizer had not researched and reached out to artists who had an online presence. But its strength was leaving the internet and putting real bodies together on the streets. I hope to see more of that type of interaction with social media from artists and activists in the future.

In the last couple of years, rad art collective organizations have not been a viable option in Montreal for me. I have moved my practise to a satellite role of supporting campaigns with necessary visuals like posters, banners, stickers and so on. I’ve been involved in different types of campaigns but most of them touched antiracism or land defense. The biggest challenge and reward has been strengthening relationships of trust. I think it’s essential and generally in critical shape today.

Outside of art, you are in grad school for Indigenous-Settler Relations, correct? Can you tell us more? How do your academic and art worlds connect?

Yikes! That is a hard question. I am in grad school and work on identifying and recognizing settler colonialism in contemporary Quebec. I would say my street art work doesn’t really overlap. It’s like I have two personas. If there is a connection, it’s because I end up wanting to both draw and write about a campaign I support. But for now, that has not happened much.