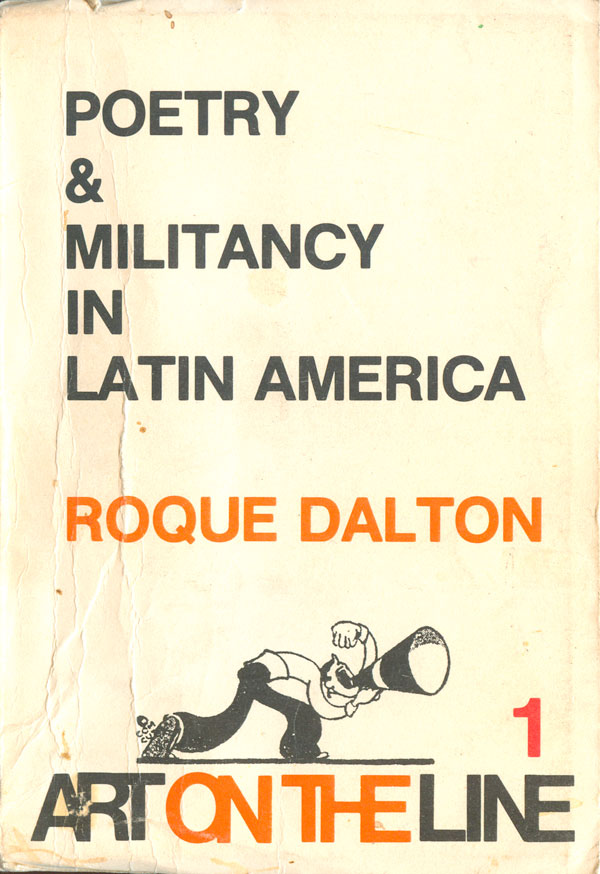

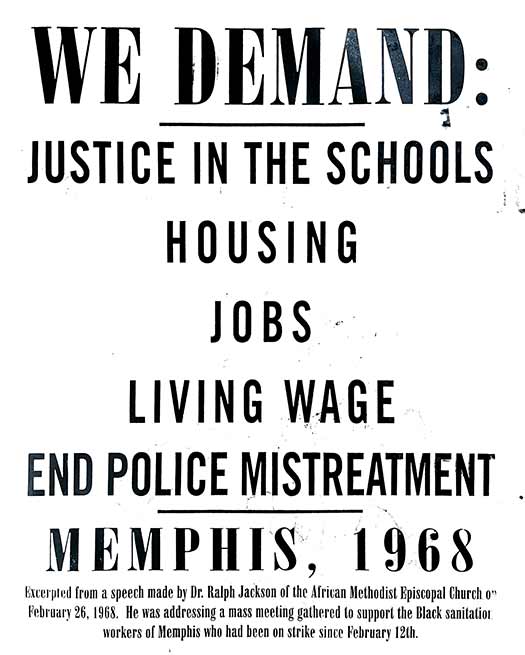

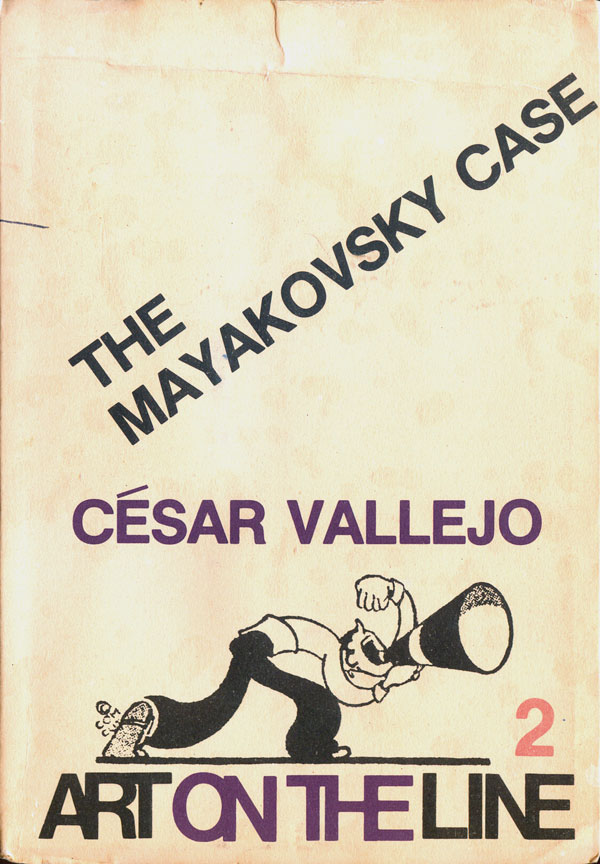

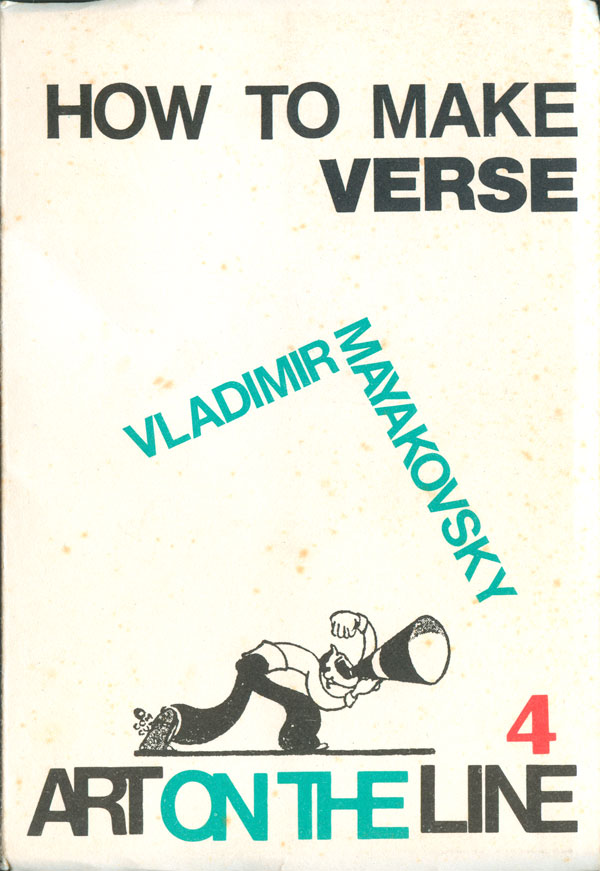

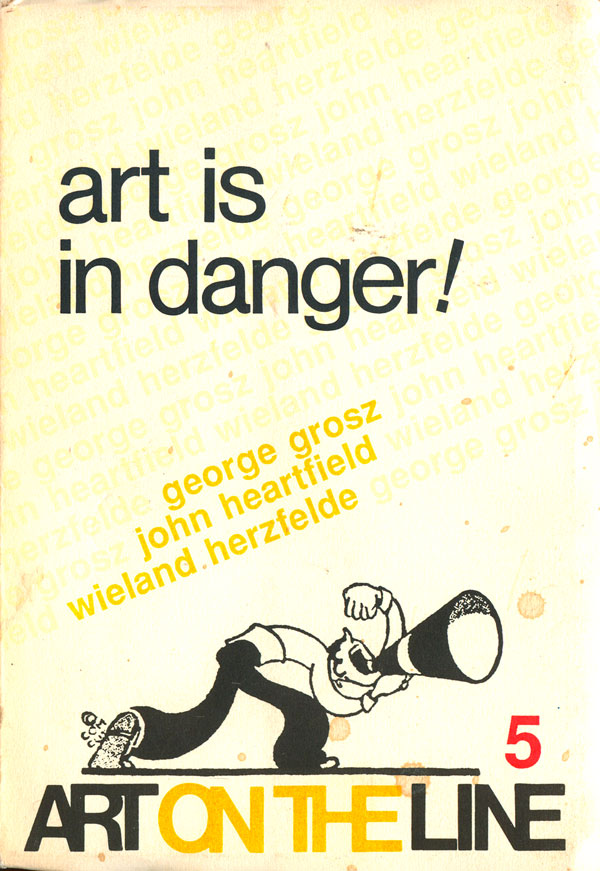

In 1981, Curbstone Press began publishing a series of small pamphlets of critical non-fiction writing by international practitioners of political art. This series, entitled Art on the Line, ran for seven years and consisted of six booklets. The first in the series is Roque Dalton’s Poetry and Militancy in Latin America. The basic design is the same as the following five publications: medium weight Helvetica type announces the title in black, and the author in a spot color (in this case, orange); the series title/logo runs along the bottom along with the issue number; and the only graphic element is an unattributed illustration of a cartoon man exhorting through a bullhorn. The books are small, 4.125″ wide by 6″ tall, thin, and easily slip into a pocket. They all have french folded flaps, the front flap blank except for the call “To the song of resistance only revolution does justice.” The back flap lists other titles in the series.

These little booklets have become quite hard to find. Some are still floating around on the internet, but often at extremely inflated prices. It’s taken me about five years to track them all down, about half for a buck or two at book sales and thrift stores, a couple I paid more than I should have at fancy used book shops, and I have to admit that one I had to track down online. The texts themselves are pretty great, if some are a bit stilted and hard to read, and the series as a whole is a nice run through ideas of revolution and art starting in the 1920s and running up to the 1970s.

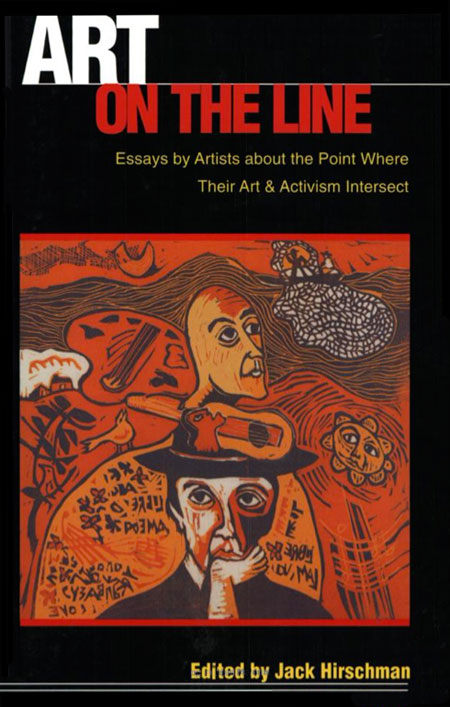

In 2001, Curbstone published an edited collection of political art writings with the same title but a new subtitle: Art on the Line: Essays by Artists about the Point Where Their Art and Activism Intersect. This book was edited by Jack Hirschman, while the original series was put together by James Scully. The initial 1/3 of the book is made up of the texts from the pamphlets, and then follows with a series of additional essays by the likes of Ngugi, Elizam Escobar, and Margaret Randall. It’s a solid collection, although there is unfortunately little of interest by visual artists.

The design, on the other hand, is a huge departure from the pamphlets. Done by Stone Graphics, the clean, open austerity of the original booklets is tossed out the window for a black background, much bolder type, and a central image which is a blockprint by Naul Ojeda. It is a nice print, but is way too busy for a book cover, especially as only one element that has to compete with titles and a slew of horizontal lines. (I guess they took the title quite literally.)