I’ve been at an art residency in Tanzania for a bit more than three weeks now, at an art space in the Mikocheni neighborhood of Dar es Salaam called Nafasi. I’m here with my partner and collaborator Erica Thomas, and we are working with the community of artists at Nafasi to come up with ideas for projects.

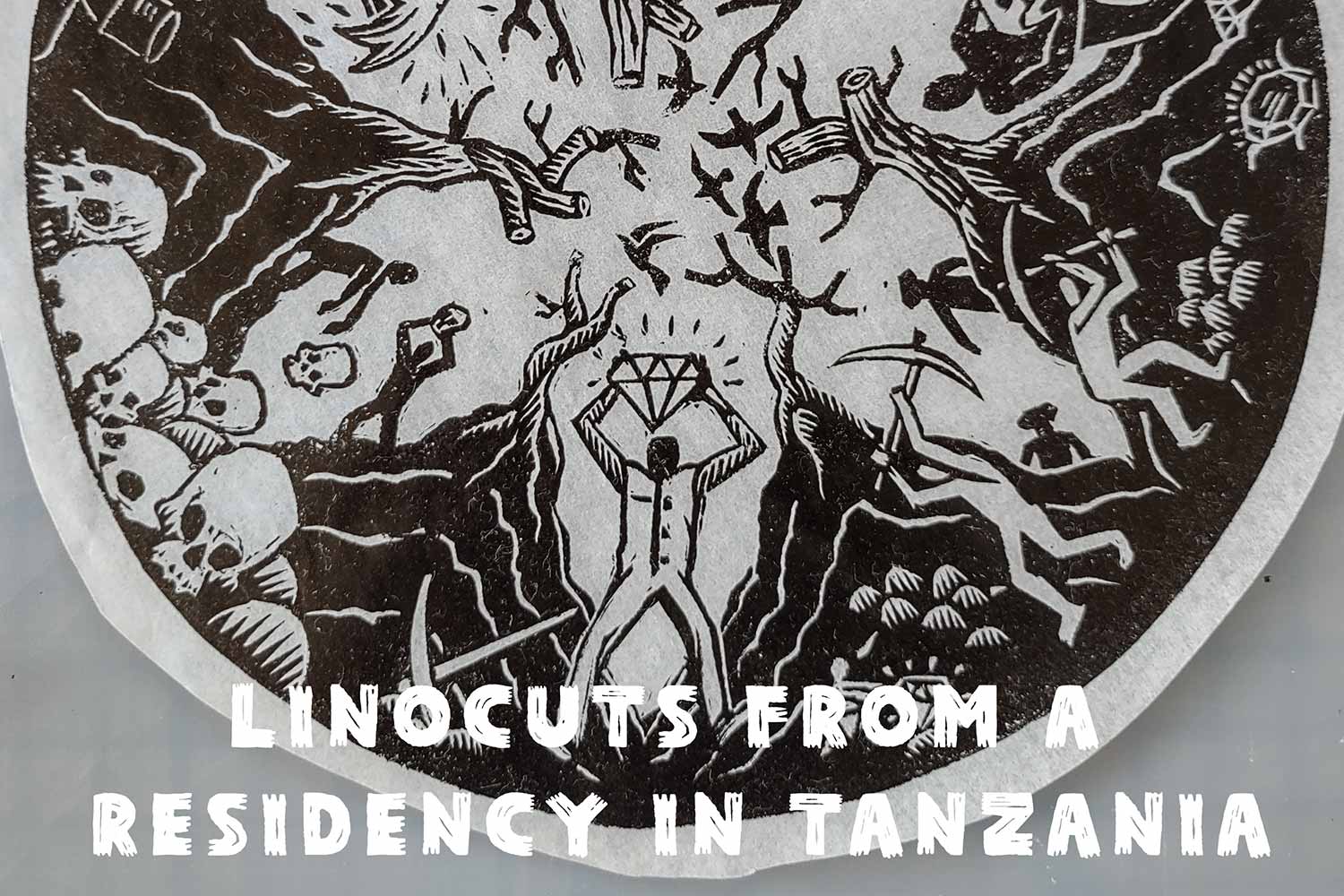

I’ve been making a few linocuts while I’ve been here, and trying to keep them all within a certain thematic structure and shape. I’ve been using divided circles as the basis for the images, and coming up with ideas based on conversations I’ve had with people at Nafasi and in the city in general, encounters with wildlife, and impressions of the history, politics and culture of this place.

Here are some images of the linocuts- I’ve enjoyed playing around with how the circular structure shapes an image into a sort of narrative. The first cut I made was based on the massive cloud of Eidolon helvum fruit bats which rises from the neighborhood just to the south of my apartment every evening. These bats make one of the most numerous migrations in the animal kingdom, and they are a pleasant golden color in the dusk.

The second cut is based on some ideas about climate and solidarity, thinking about floods and clouds and how we help each other escape them.

The third features the African Jacana, a wading bird with comically large feet that I saw while checking out a pond at dawn at the local university, and also several hours later at a wetland surrounded by new homes. I was imagining the bird here trying to navigate its new circumstances with the same feet it uses to pad from waterplant to waterplant.

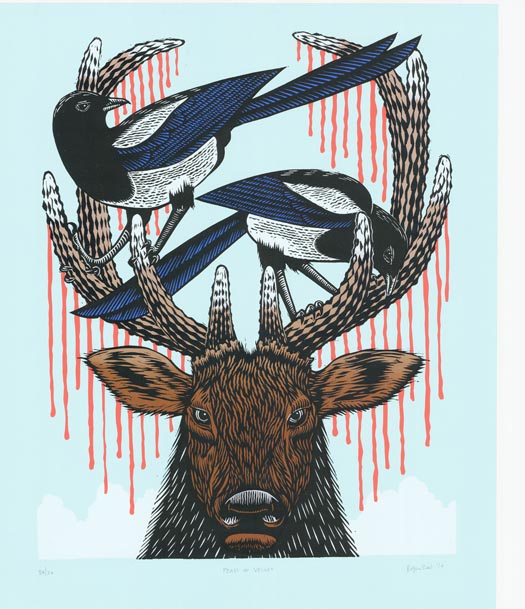

I’ve tried to incorporate some discussions of value and resources into these images- one of which tries to think about knowledge production, and the relationship between colonial science, tourism, trophy hunting and a commodified environment.

People come from all over the world to spend a lot of money viewing Tanzania’s profuse wildlife communities, and this has created a lot of pressure on those communities and the human societies that live among them. Currently the government is planning to strip title to 70,000 Masai people in the Ngorongoro crater for exclusive access to high-dollar trophy hunting junkets, something which is being justified by saying that the Masai are living in squalor with no access to education and need to be moved off their ancestral lands in order to properly receive social care. I recently learned about the hashtag #upuusiwakitenge, which translates loosely to “separation nonsense” (and also refers to a politician pushing for the removal) which Tanzanians are using to speak out against the resettlement. The core of the idea behind that hashtag seems to be a specifically anti-colonial pushback to the idea of a fortress conservation, namely the Western idea that wildlands and wildlife need to have territories set aside for them where humans do not reside, so that there can be a firm and clear zone of demarcation between humans and animals.

The history of this idea is complicated, but rooted in the history of how the West’s colonial administrations saw the territories that they were administering- and how the affection and awe that those administrations had for the epic wildlife communities of East African savannahs was transmuted into an ideology that informed them they were the proper stewards of these populations of wildlife, and that the local residents were destined to destroy them, and themselves. We see it’s echoes in our national parks and wilderness areas in the US. It’s a complicated situation, but the idea that indigenous peoples with ties to the land should have a greater say in land management is the only obvious solution, even if that does imply some sort of economic relationship with protected landscapes.

#Upuusiwakitenge (check it out, use the translate function on Twitter) is the first time I’ve seen people voicing a popular rejection of that idea, and it’s very interesting to see and hear after many years of only reading about these ideas in books. I’m hoping to find someone who can talk to me a bit further about it while I’m here.

The other more narrative linocut is based on some ideas about mining, exploring some ideas about who gets to keep the value of the land, and how we asses the value of the various things we find in the earth. Tanzania’s mining sector is the 2nd largest tranche of the economy, mostly in precious metals and minerals. A new pipeline was just approved- crossing into the country from Uganda to the north and transporting oil to terminals on the Indian ocean, with an expected capacity of 216,000 barrels a day.

The last cut so far is of a lion’s mane jellyfish, which I had the overwhelming pleasure to encounter at about 60 feet down on a dive off Mafia island. A legendary mass of tendrils, flaps and fronds, it was very hard not to hug it.

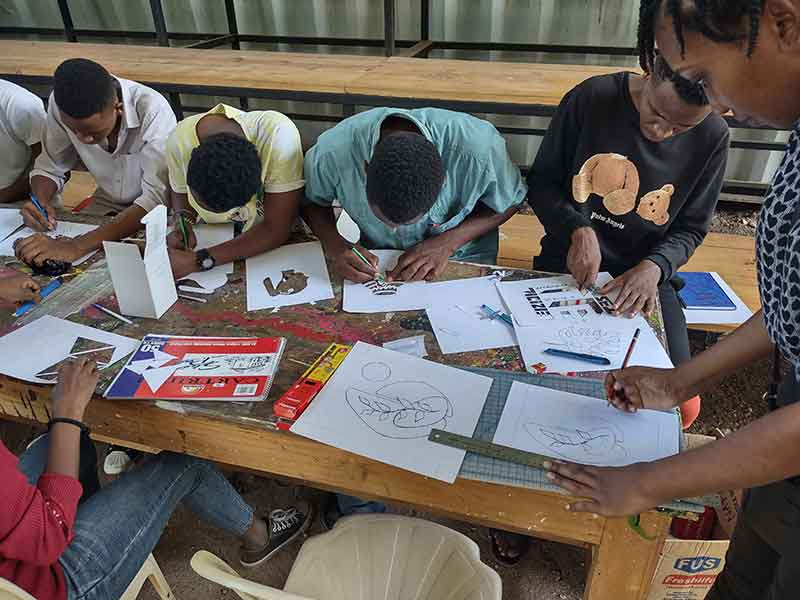

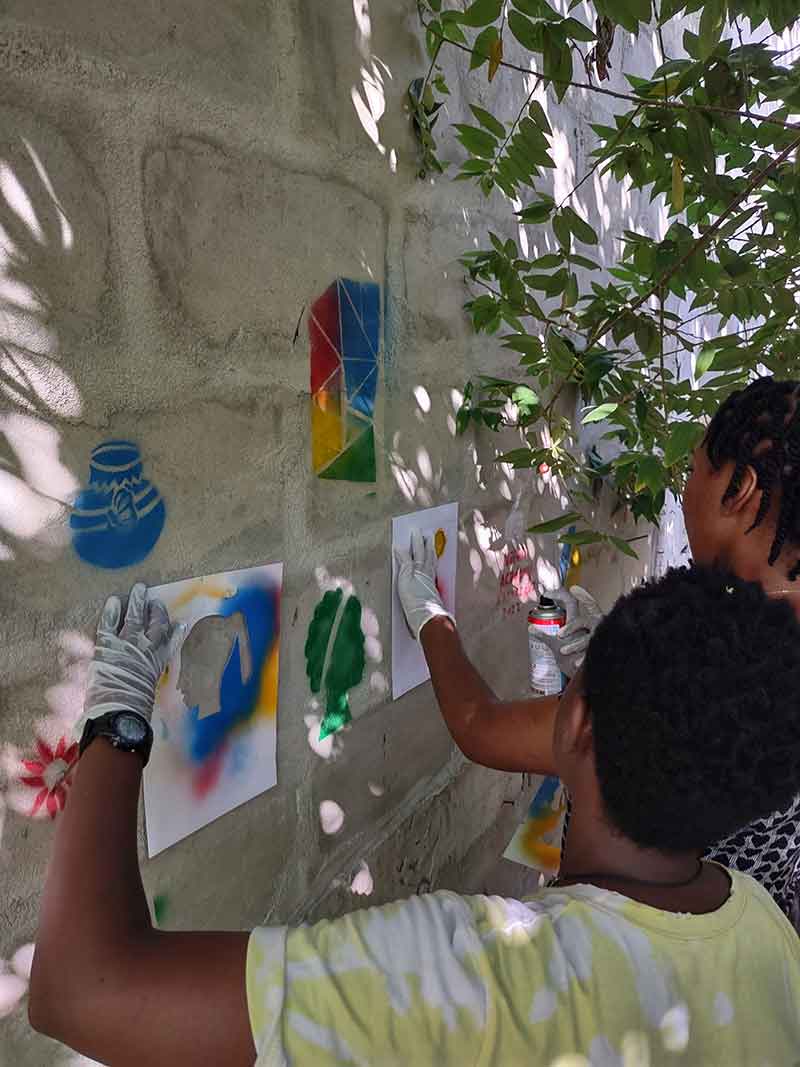

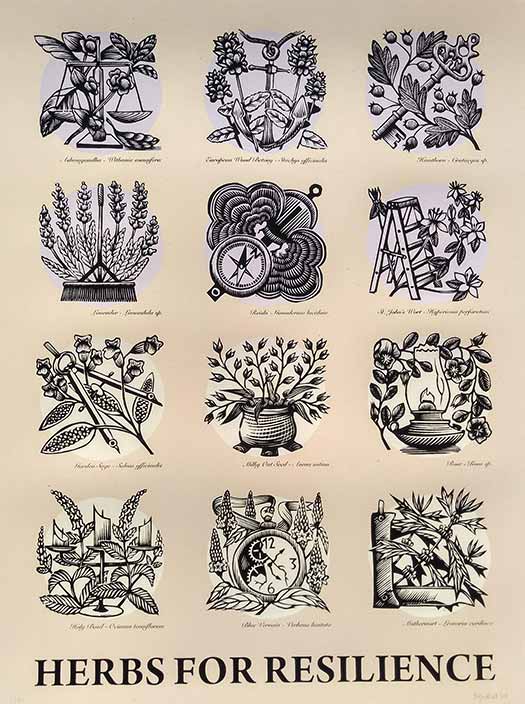

Finishing up: here are a few images from a stencil workshop with students at Nafasi Academy, an arts intensive program that Nafasi is running this month.

I loved the ideas and creativity…congratulations