An independent journalist, referred to by the Mexico Solidarity Network as an “unidentified Chicano,” reports:

May 15, 2006: It’s National Teachers Day in Oaxaca. And the leadership of Oaxaca’s 70,000 teachers representing Section 22 of the National Teachers Union declared that if there was no further movement in their negotiations with the government, then the following week “would see a state-wide strike by Oaxaca’s school teachers” and that “This one will be different than all the previous strikes”…

May 22-24, 2006: 70,000 Oaxaqueño school teachers go on strike. And the first indications that this was to be a “different” kind of strike were immediately apparent in and around the city’s historic centre. There, for the first time, the teachers, in the thousands, erected a tent and awning city, occupied day and night in the Zocalo and in the streets surrounding the Zocalo. It’s a peaceful occupation of the city’s center, but it is also immediately apparent that more teachers are coming into the occupied area on a daily basis. And these teachers are not just from the City of Oaxaca. They’re swarming in from the outlying villages and towns in the Valley… (Mexico Solidarity Network Weekly News and Analysis, August 21-27, 2006)

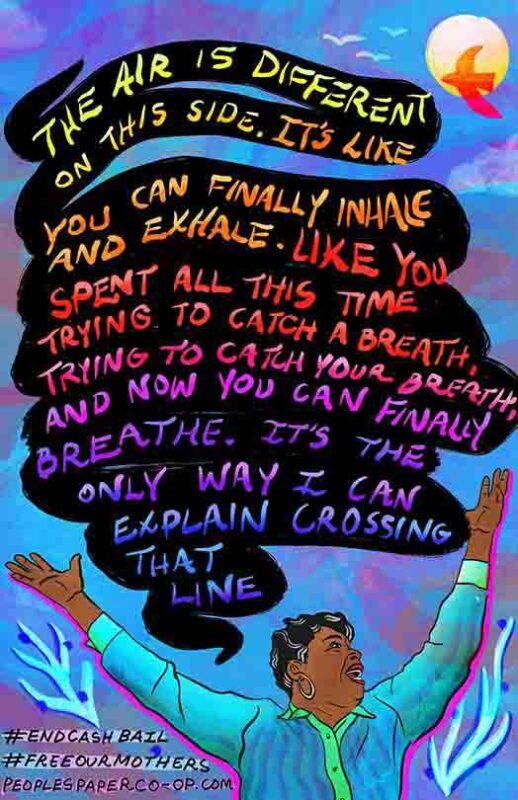

The teacher’s strike, their encampments, their independent media infrastructure, and their continuous mass mobilizations (marches reaching up to 300,000 people) have been perceived as a serious threat to Mexico’s dominant political and economic order. In the early morning of June 14, 2006, the state attempted to crush the teacher’s movement by launching an army of several thousand uniformed and plain clothed state and municipal police in an all out attack against the teachers. Police violently destroyed the encampments and scattered the teachers throughout the city.

Within two days, the teachers released the names and photos of 12 teachers and 3 students who were killed and/or disappeared during the attack. The government denies the charges. To date, it is confirmed that five union members have been shot and killed by police.

Government repression also persists. Police continue to attack and kill members of the APPO, a recently formed network of organizations sympathetic to the teachers strike and dedicated to removing Governor Ortiz from power. On August 22, 2006, police attacked APPO members who were guarding commercial station La Ley 710, killing Lorenzo San Pablo Cervantes, head of the education sector of the state Department of Public Works and an APPO sympathizer.

For more information check out these websites:

narconews.com (English)

Mexico Solidarity Network News and Analysis (English)

Indymedia, Mexico (Español)

Indymedia Mexico, Desalojo Oaxaca (Español)

Centro de Medios Libres, DF (Español)

Indymedia, Chiapas (Español)

To learn more about the historical context of Mexico’s teachers movement, come to a special movie screening of Granito de Arena. August 31st, 8pm. Times Up!, 49 East Houston (bet. Mott and Mulberry)

Granito de Arena: Award-winning Seattle filmmaker, Jill Freidberg (This is What Democracy Looks Like, 2000), spent two years in southern Mexico documenting the efforts of over 100,000 teachers, parents, and students fighting to defend the country’s public education system from the devastating impacts of economic globalization. Freidberg combines footage of strikes and direct actions with 25 years worth of never-before-seen archival images to deliver a compelling and unsettling story of resistance, repression, commitment, and solidarity.

The pictures in this post were taken by Sasha Hammad. Thank you to her.

By MARC LACEY

Published: December 28, 2006

OAXACA, Mexico, Dec. 21 — There is a new smell in the air here, competing with the aroma of mole sauce that routinely wafts through Oaxaca. It is the smell of paint fumes.

Skip to next paragraph

The New York Times

Protests are as much a part of the culture of Oaxaca as its cuisine.

Work crews are everywhere, retouching the colonial facades that give Oaxaca its charm and draw tens of thousands of visitors a year. But in this politically charged city in southern Mexico, where protesting is as much a part of the culture as the distinctive cuisine, even the cleanup is causing arguments.

Just weeks ago, Oaxaca was a wreck. Graffiti marred its buildings. Burned-out vehicles blocked its roads. Angry protesters confronted riot-equipped police officers around the charming central square.

The protests, which began with teachers seeking a pay raise but grew to include an array of leftist groups and indigenous organizations, are continuing sporadically, but officials have begun trying to scrub away the evidence of what occurred.

Not everybody agrees on the best approach.

Carlos Melgoza, director of the Institute for Cultural Patrimony of Oaxaca, which is responsible for sprucing up 482 blocks and 21 memorials in the city, intends to use high-pressure machines to spray sand onto limestone facades to grind away the painted slogans.

But Rafael Bergara, who helped in the effort to persuade the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization to designate Oaxaca as a world cultural site in 1987, has argued in the local press that such an approach could do more harm than good and end up permanently damaging the structures.

Cost estimates are also at odds. The National Institute of Anthropology and History put the damage at $30 million. The Institute for Cultural Patrimony of Oaxaca says the cost of repairs will be less than a third of that. Estimates from other experts similarly vary widely.

Such back-and-forth is nothing new in Oaxaca, where historic preservation is a topic close to many hearts. When McDonald’s planned a restaurant in the central square some years back, Oaxacans took to the streets to keep the burger joint out. Some residents still resent the conversion of a 16th-century monastery into a luxury hotel.

“There’s always a debate about everything in Oaxaca,” said Jorge A. Bueno Sánchez, director of the botanical garden. He noted that Oaxaca, which is on an earthquake fault and has had quake damage at various times over the years, has experience remaking itself. “We’re used to starting again,” he said.

At the height of the protests, which began in the summer, Oaxaca was a shabby version of its former self. The slogans painted on surfaces everywhere shouted “Assassin!” and “Get Out, Ulises!” among other things.

Put up by followers of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca, a loose coalition of protest groups, the messages were aimed at Gov. Ulises Ruiz, whom many Oaxacans accused of engaging in heavyhanded tactics in breaking up a teachers’ strike in June and ignoring the people of the state.

The protesters have not changed their demand that Mr. Ruiz resign, but the authorities have rounded up many top leaders of the protest coalition. The federal police, who took back the center of the city from protesters in October, ceded control of Oaxaca back to state law enforcement officials this month.

The protesters say they have not given up, but the painting and scrubbing continues.

Private companies have adopted blocks around the central square and have begun repainting buildings there in their vivid blues, reds and yellows. Some of the graffiti is proving hard to wipe out, though.

The giant “666,” the apocalyptic biblical reference that someone scrawled on the front door of the 16th-century Santo Domingo Church, is still visible. Burn marks on some of the limestone outside the church, and in other parts of the city, are reminders of the bonfires that lit the evening air during the protests. Windows remain smashed, including those on the American Consulate here.

Still, Francisco Toledo, a noted Mexican artist who pours much of his wealth into buying up historical properties and preserving them, said the damage that protesters had left was not as bad as that committed by skateboarders who wore down the limestone with their boards, and drunks who threw bottles at historic artifacts.

“The city was not well taken care of before this,” Mr. Toledo said. “Now it’s worse.”

Claudia López Morales, an architect active in restoring Oaxaca’s historical structures, is philosophical about the effects of the protests that remain visible. “Some of this damage will always be visible, and maybe that’s not bad,” she said. “What happened is part of our history.”

As she walks the cobblestone streets of Oaxaca, she said, she feels a mix of emotions. “There’s more damage to the heart of this city than to the buildings,” she said. “We can paint everything, but how do we repair our heart?”

Mr. Ruiz, in a recent speech, spoke of his desire to reconcile with the protesters and salve the wounds of the community. “We want a new Oaxaca,” he said. But many saw that as just talk and said that they were not buying it.

Jesús Sánchez Alonso, an economics professor at the Oaxacan Technological Institute who sympathizes with the protesters, says the real cleanup that Oaxaca needs is of its corrupt and arrogant politicians.

“The government doesn’t want to change things,” he said. “They want to paint. They want cosmetic changes.”

Nice site you have!