I had been planning a mural in Asheville, NC for months, had a ticket, ordered paint, and was all set to fly out and start painting on the 7th and when news came through that a key bureaucrat had retired just before signing a critical form, and that the project was on indefinite hiatus. With plans scuppered, I was busy complaining to friends about the system when one offered an alternative- travel to Standing Rock and help to build some winter structures for the water protectors, and then paint a mural on them.

My friends Esther Forbyn and Matt Musselwhite coordinated an impressive solidarity effort called Shelter for the Storm, bringing together the resources of rural communities in Southern Oregon to fell dead trees and mill them into boards, roll out sheets of steel roofing, donate woodstoves and hardware, and assemble the bones of two modular buildings intended to provide warm shelter for the water protectors during the freezing plains winter. I left Portland in the smoking aftermath of the presidential election and traveled with the crew and the giant pile of materials to the Oceti Sakowin camp in North Dakota, where we spent a week assembling the structures, entirely powered by a couple of banks of donated solar panels. The structures were created for two indigenous media groups doing frontline documentation of the #NoDAPL struggle, and our work was part of a frenzy of building and insulating activity going on all around the camp as temperatures plunged.

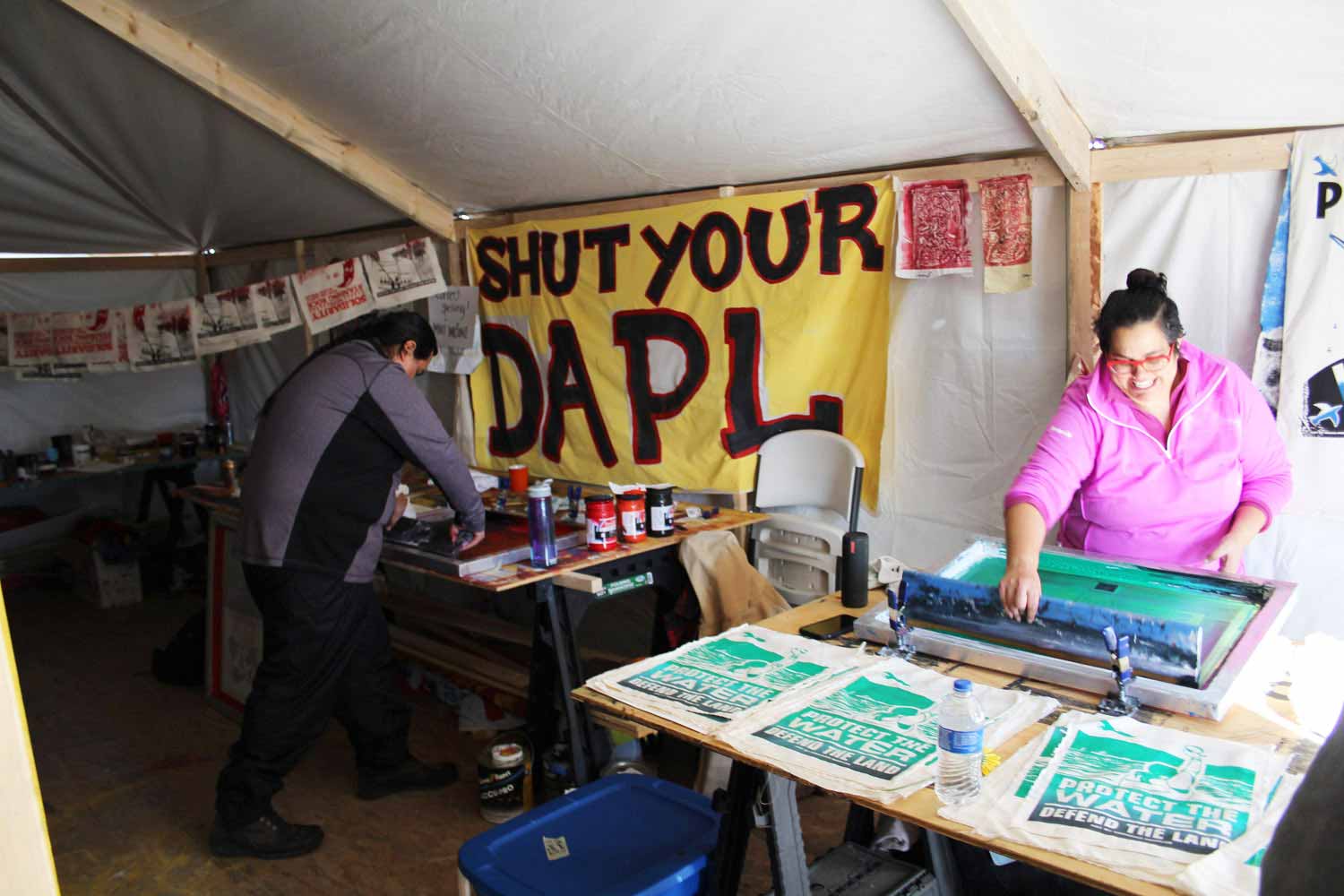

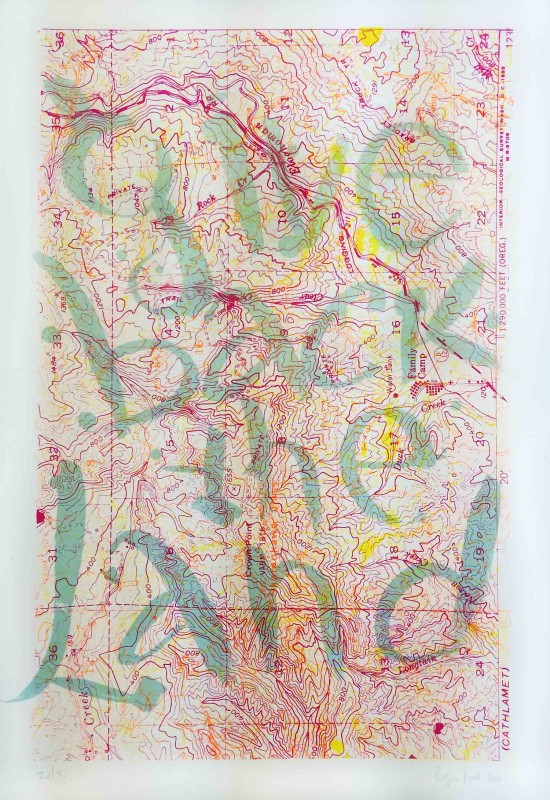

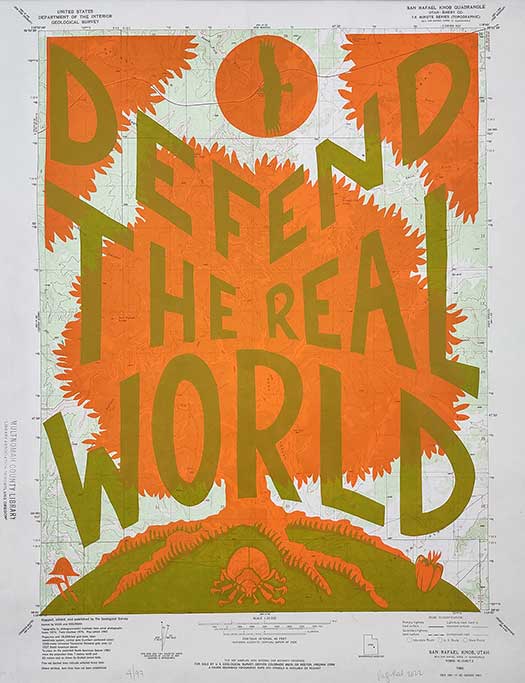

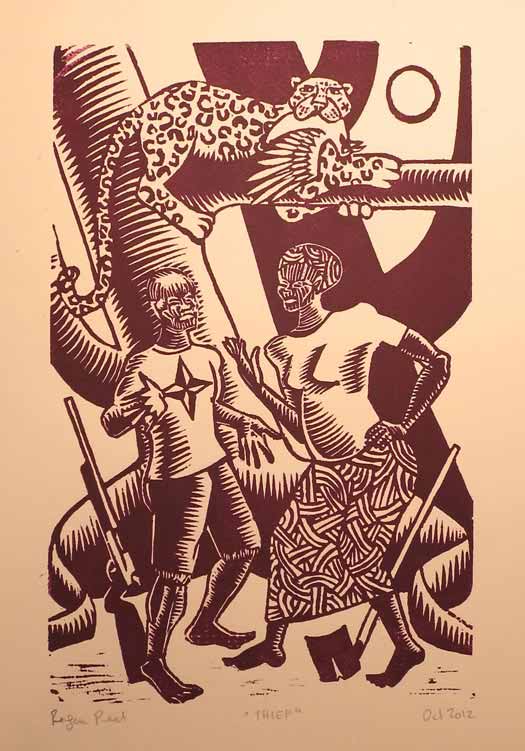

I spent a couple of afternoons in the art tent, working with fellow Justseeds artists Melanie Cervantes and Jesus Barraza first and Nicolas Lampert and Paul Kjelland later.

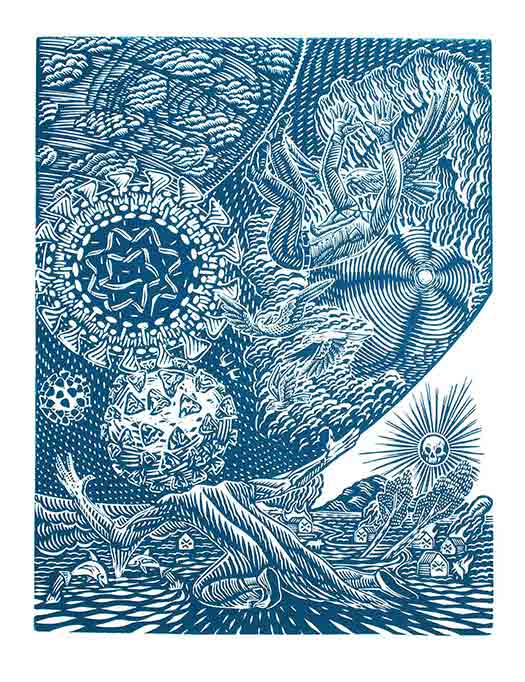

As the latter structure at Southwest Camp was nearing completion, I started painting an image of the Dakota Skipper, a small and beautiful butterfly whose habitat is being destroyed by pipeline development. The skipper is federally listed as endangered, but the US Fish and Wildlife Service gave Energy Transfer Partners a pass to dig through the grasslands where it lives- one further example among many of the collusion between the state and private capital that defines this awful project.

Portland-based Diné media activist Chris Francisco noted that the Diné word for butterfly is Gálíígíí, so I painted that on the side of the building. Manitoba muralist Jackie Traverse came by with a crew of women from the north and painted another beautiful mural on the other side.

The night before we left, the police assaulted protectors on the blockaded 1806 bridge, flash-bangs arcing and exploding in the freezing air, the mysterious Cessna circling overhead with its’ running lights off, the water cannon hosing across the assembled defiant protectors like a malevolent white snake. Chants rose from the hills overlooking the violence, and green-blinking drones buzzed around us, fat and bulbous as giant idiot bees. It looked like the future- like I had come to the raw boundary between two worlds- one native-led and native-voiced, guided by indigenous traditions and leadership and focused on a principled spirituality tempered by physical resilience, and the other black as night and speaking in prerecorded amplification, shouting poison and explosions to the stars. I left the next morning to return to Portland, traveling through Trump country back to the warm forest womb of the coast.

The struggle at Standing Rock is intoxicating in its clarity. It is about five centuries of dispossession, about broken treaties, and about virulent, vituperative racism. The water protectors have pulled off the mask- let’s all look into this abyss and find out our own ways to overcome it. Most important, of course, is to put our comfort aside and get uncomfortable- and get in the way. After the recent eviction orders for the Oceti Sakowin camp from the Army Corps and the State of North Dakota, Chris sent me the photograph below and the message: “We won’t give up. Water is Life!”

See you in the future.

Thank you! The photos are exquisite and the stories are delicious.

Why hasn’t the Obama Administration stopped this?