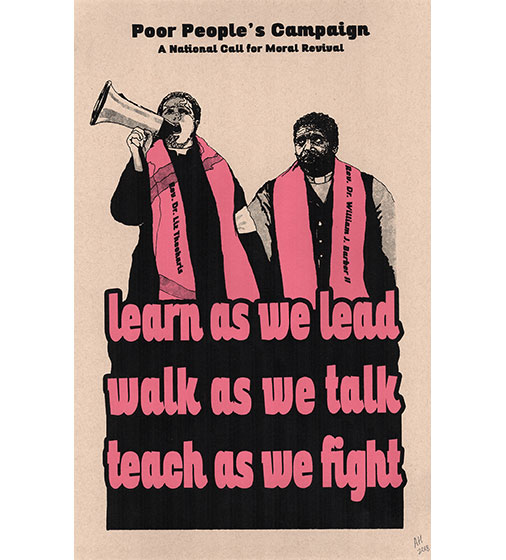

The new Justseeds Poor People’s Campaign portfolio is just one example of artists getting involved with this self proclaimed “new and unsettling force.” Over the past several weeks the campaign has been conducting mass actions filled with singing and beautiful banners followed by civil disobedience to gain exposure for the campaign. This integration of art and action is not a new strategy, fifty years ago the original Poor People’s Campaign was using art, music, poetry, etc. to bring people together, share ideas, and build solidarity.

Inspired by this history, artists, singers, writers, and curators such as Washington DC based Natalie Campbell and Nick Petr have been getting involved with the new Poor People’s Campaign and using art as a tool for popular education that connects the current actions to the historic campaign. Specifically, Natalie Campbell and Nick Petr partnered with the Washington DC Public Library to develop a project that celebrated and reinterpreted the original Poor People’s Campaign: Hunger Wall.

I was really interested in what they were doing, the history that they were pulling from, and the community they were engaging, so I reached out to learn more about their project thinking that others might be just as interested.

Aaron Hughes (AH): You are collaborating with local Washington DC artists to bring attention to not just the current Poor People’s Campaign but also the history of the campaign. How are you bringing the 50th anniversary of the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign to life through art?

Natalie Campbell and Nick Petr (NC & NP): We’re both independent curators, and we were presented with an opportunity to work with the DC Public Library to think about how to celebrate this history in a way that uplifts and enhances the work already being done here. With support from the DC Public Library Foundation, we have been working with librarians and artists to create projects inspired by the three key cultural centers of the original Poor People’s Campaign:

- The Poor People’s University, which hosted talks and teach-ins.

- The Many Races Soul Center, also known as the Soul Tent—a performance and gathering space where figures such as Muddy Waters, Dorothy Height, and Jesse Jackson performed, spoke, and rallied.

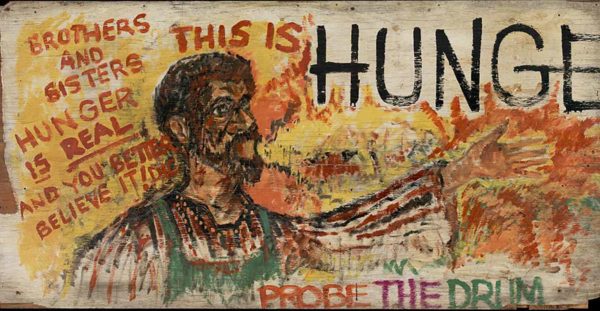

- The Hunger Wall, which was a plywood mural where activists from different races, cultures and regions of the country drew and painted messages of solidarity in the human rights struggle.

Section of the original 1968 Hunger Wall

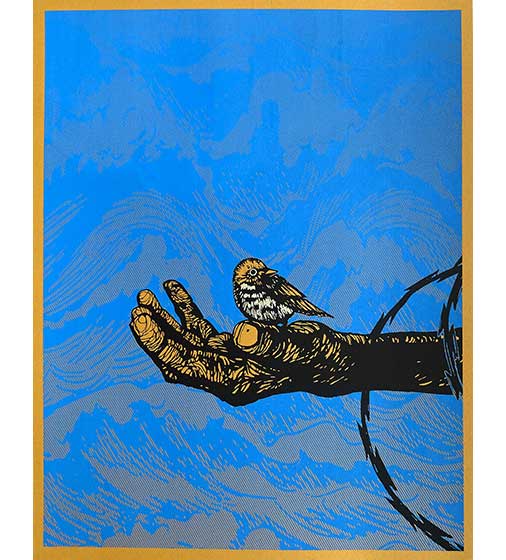

The original Hunger Wall mural is now in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, but we worked with a group of DC artists using contemporary graphic design and street art styles to reinterpret the Hunger Wall as a poster series.

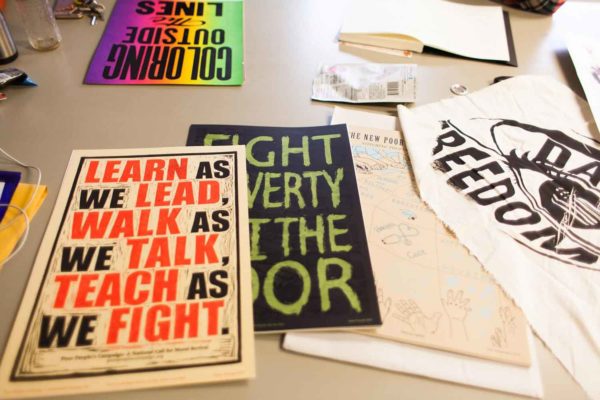

Beyond this projects, there are so many events happening throughout the DC Public Library system to commemorate this anniversary year. So we sought to approach this project not just as a celebration of 1968, but as a way of talking about this history in the context of today. There are more than 45 million people living in poverty in this country and that’s no more acceptable today than it was in 1968. For example, we used the portfolio created by Justseeds for the new Poor People’s Campaign as a jumping off point for asking local artists how they see the issues of poverty, racism, militarism, and environment impacting DC communities today.

We were excited to add these local artist commissions to the portfolio and to be distributing Justseeds posters in DC!

Photo of Shaw (Watha T. Daniel) teen wheatpasting workshop by Olivia Weise.

AH: Please say a bit more about your plans and what you did with the DC Public Libraries?

NC & NP: In short, we wanted to activate the library as a site of cultural production; connect local community members (artists, librarians, and patrons) to a national conversation about building an equitable society; and engage a new generation with the historical material—the historians, the collections, and the still-living participants and witnesses to that history— in their backyard. And, the fact that the Poor People’s Campaign re-launched this year means we can connect local people to the organizers continuing Dr. King’s work today.

Everyone knows the library as a place to take out a book, to go to receive information, learn skills, get access to resources. In DC, the libraries are vital community spaces. There are meeting rooms throughout twenty-six branches (and soon the renovated central Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library). With that in mind, we wanted to push on what it means for the library to truly take on this role as a community space and engage the community more broadly through arts and culture.

We’ve also been working with a group of librarians through a special partnership between the DC Public Library and the Maryland Institute College of Art MFA in Curatorial Practice. The idea is to develop methods for librarians to build on existing programs and develop new ones, generate new tools for outreach and audience development, and more effectively meet the needs of the communities they work with day in and day out. Public librarians do much more than help people find books and log into free internet—they are public educators, social workers, and at times even provide medical assistance. Librarians are working in the trenches and often figuring out how to do so with limited resources. We wanted to change that.

AH: You mentioned earlier that today, there are some 45 million people living in poverty in the United States, that seems to really resonate with the historic issues of structural inequality that the original Poor People’s Campaign was trying to address. In what ways do the themes of the 1968 campaign resonate today with the issues communities are facing in DC and your work at the DC libraries?

NC & NP: 2018 is a year filled with protests and actions in response to issues of inequality and injustice—from school walkouts to the New Poor People’s Campaign. DC currently ranks in the top five for highest rates of homelessness in the nation, and recent data shows that the homeless population here is growing faster than any city in the U.S.. Housing costs have skyrocketed in the past few years and the job market here can’t keep up (a national trend). At the same time, there are few places that embody the spirit of Resurrection City more than the DC Public Library; the Library provides services on a massive scale throughout DC’s communities, and if you ask anyone, they will tell you that libraries are one of the only spaces that truly anyone can occupy, be safe in, and use to support the basic needs of their life and personal development. A day at any neighborhood library is a window into the richness of DC communities, from sound artist meet ups to teen mentoring programs to Coffee and Conversation programs with adult patrons. So, while librarians are often at the frontlines of inequality and the most urgent issues impacting residents, they are also more plugged in than anyone else to the richness of community resources. In our view this makes DC Public Library one of the most vital resources in the District right now.

Courtney Dowe, Poor People’s Campaign activist, performing in DC Public Library’s Soul Tent installation at Mt. Pleasant Library. Photos by Anu Yadav.

AH: You invited local artists to respond to the themes of the new Poor People’s Campaign; who are the local artists that got involved and how did they respond to specific themes?

NC & NP: We challenged our artists to reinterpret the 1968 Hunger Wall, a mural painted on plywood in original Resurrection City by activists from many backgrounds expressing slogans of solidarity among races, ethnicities, and parts of the country—you can see the original here. The idea of painting and drawing over existing imagery, annotating messages to express a common struggle, resonates with the four artists, each of whom uses art as a tool for resistance and social justice, drawing upon contemporary visuals from street art and graphic design.

We worked with a local curator/collaborator, NoMüNoMü, to come up with a visual language and invite artists with substantive connection to these issues. Early on we held an all-day workshop with the poster artists and went through the history of the Poor People’s Campaign and the role that arts and culture played in organizing people across color lines and social differences in 1968. We looked at materials from the library’s Poor People’s Campaign collection and then at the Justseeds Posters and other ways that today’s campaign is utilizing arts and culture as an organizing tool.

We discussed the moral issues being addressed in 1968 and 2018 through this movement: poverty, racism, war/militarism, and ecological destruction and how the artists see these issues locally.

Images of poster planning meeting. Photos by Olivia Weise.

AH: That sounds like a powerful program. Can you tell us a bit about each of the new poster designs and their significance?

NC & NP: Sure:

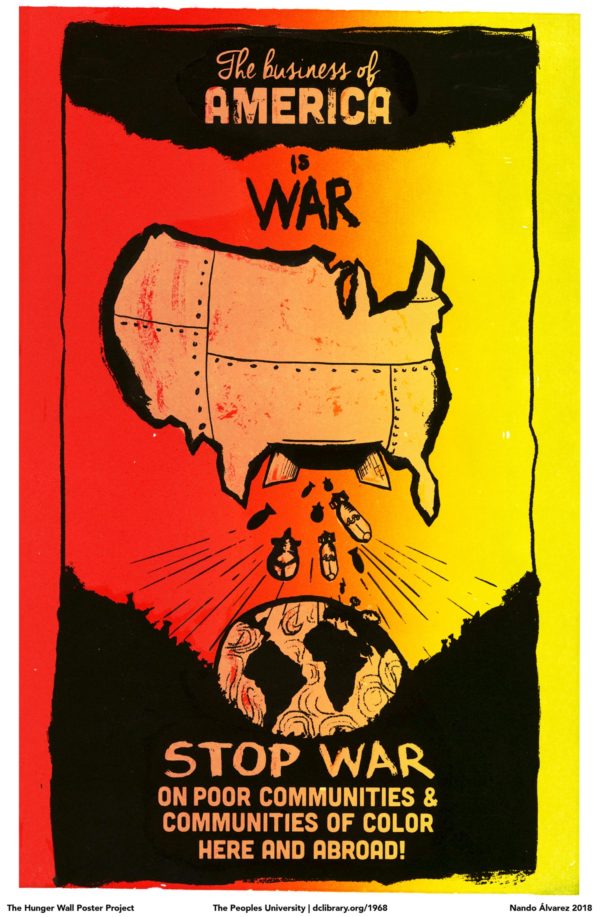

The Business of America is War by Nando Álvarez

Nando Álvarez (@nandoalvarezr | http://www.nandoalvarezr.com/) is an Ecuadorian visual artist currently based in DC, with a background in advertising and photography. His current body of work incorporates photography, screen-printing, illustration, and other media. His artwork is moved by a complicated reflection on colonization, hegemony, patriarchy, white supremacy, and other forms of oppression. A member of the social justice art collective The Sanctuaries, Álvarez connects directly with the community to make art that responds to practical needs for the struggle.

About his design Nando noted, “I tried to reflect on one of the evils that MLK talked about until the day of his assassination. Militarism, as he called it, is still relevant today, probably more than 50 years later, as wars for profit keep destroying the soul of this planet. War is waged mainly on poor communities, communities of color.”

Download the print here.

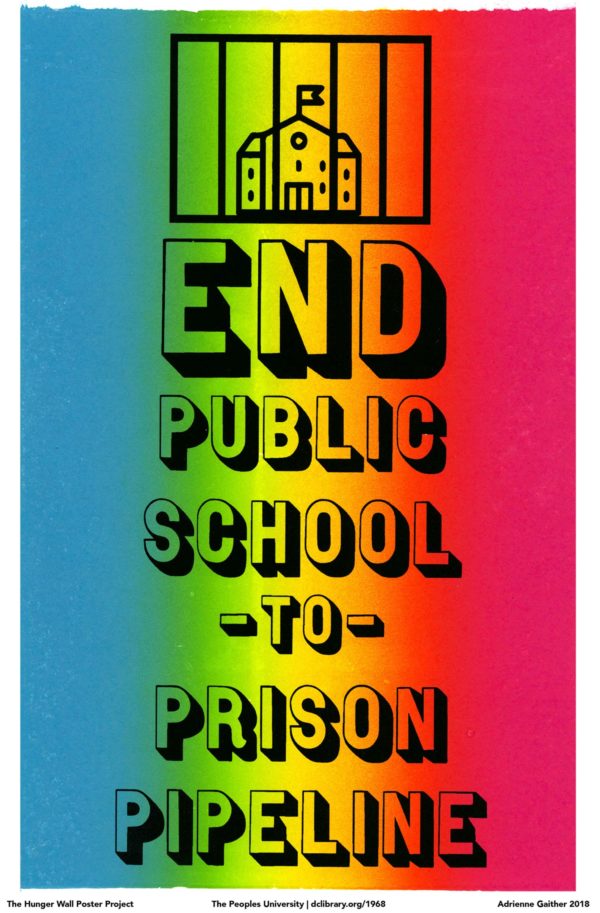

End Public School to Prison Pipeline by Adrienne Gaither

Adrienne Gaither (@rockyyoadrienne | http://adriennegaither.com/) is a DC based artist whose work explores identity and black imagination through paintings and installations. Her work attempts to challenge ideologies that perpetuate hierarchical structures. Gaither’s work reflects her deep interests in political histories and personal narratives incorporating footage from old archives and contemporary news into subversions of geometric abstractions.

About her design Adrienne noted, “My poster was inspired by working in education and the issue of racism in the original Poor People’s Campaign… the data for public schools and suspension especially in cities for students of color is alarming. Private prisons use third-grade data to plan for prisons—that is terrifying … Not only are black and brown children targets in their day to day, they become targets in a space that is supposed to foster and nurture their minds.”

Download the print here.

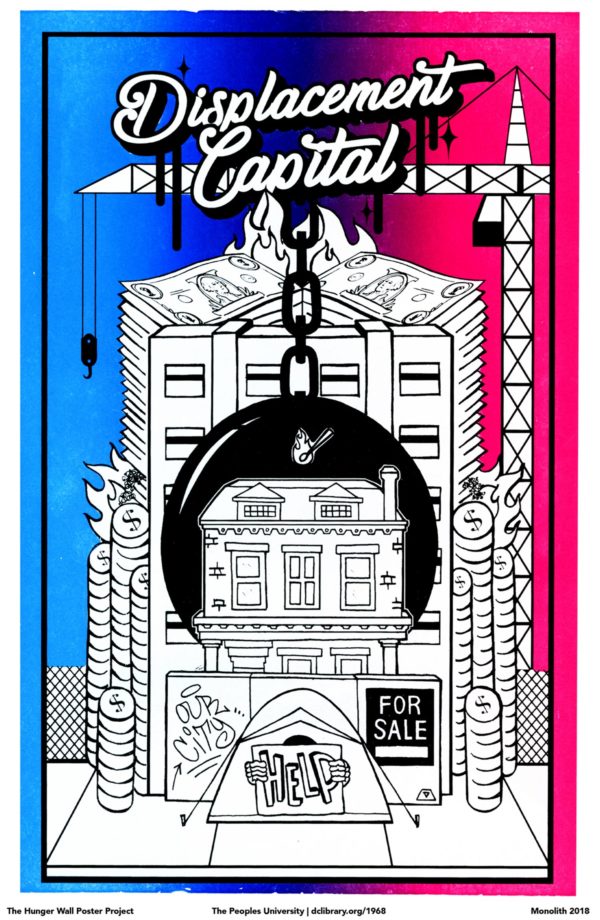

Displacement Capital by Monolith

Monolith (@monolithdc | http://411collective.com/) is a DC based artist whose work is driven by political philosophy, pop culture, typography, and a passion for social justice. They believe that art forms born in the streets, graffiti and street art, can reclaim space overcrowded by eyesores of capitalism and advertising. A co-founder of the 411 artists’ Collective, Monolith uses street art to elevate the creative language of resistance, as one of the few remaining avenues of expression and culture in local communities facing rapid gentrification.

About their design Monolith notes, “This poster focuses on one of the four evils of capitalism, Poverty, addressed in the Poor People’s Campaign. DC is one of the leading cities in the country undergoing rapid and violent gentrification, displacing poor people of color and destroying the culture and soul of this city. Staple DC rowhomes and familiar neighborhood establishments quickly transform into mini condos, yuppie shops, and hipster bars. Names get replaced, like Malcolm X back to Meridian Hill Park, named after a rich commodore’s mansion.”

Download the print here.

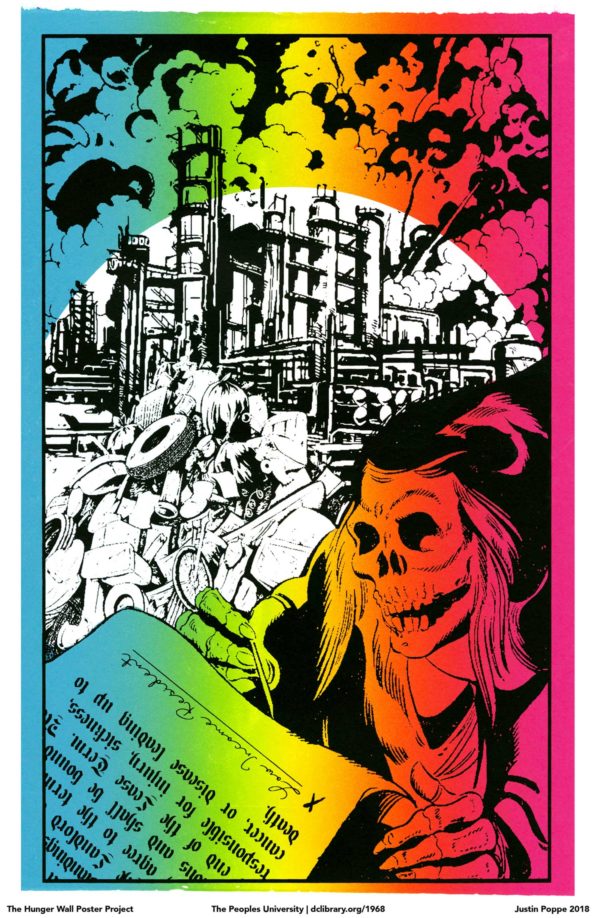

Justin Poppe: The Lease Agreement

Justin Poppe (@411collective | http://411collective.com/) is an artist who has been based in Washington, DC since 2008 and has exhibited around the DMV area since graduating with a BFA from the Corcoran College of Art in 2010. He works on canvas using a mix of screen printing and painting techniques and also creates large scale murals on a variety of subjects. In 2016 he and Monolith DC co-founded the 411 Collective; their focus is creating visual art for social justice movements on both a local and national level.

About his design Justin notes, “This piece is based around the concept of environmental racism. The practice of putting toxic health hazards such as power plants, landfills, and chemical producing industries around low income neighborhoods with no concern for the residents’ health and well being has been going on for generations and generations and has to end now!”

Download the print here.

Photos courtesy of the artists.

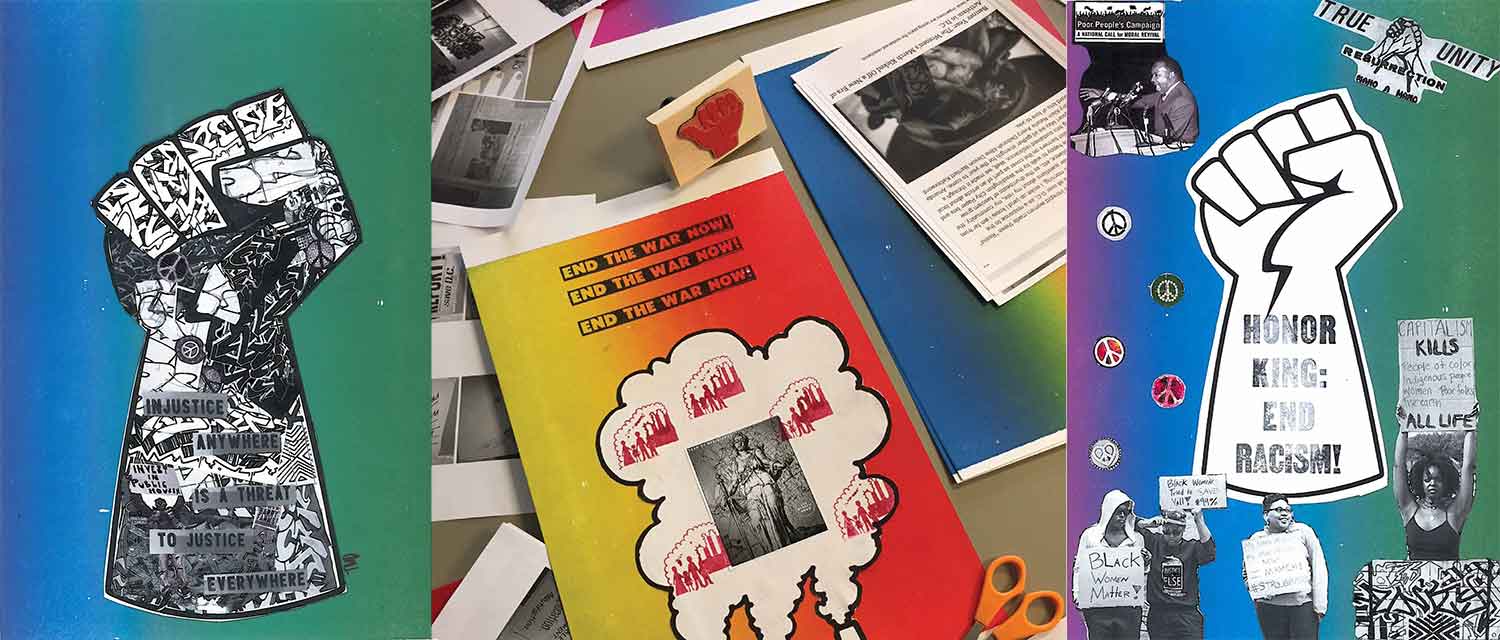

AH: You also developed poster-making kits that can be used in workshops across DC. Can you talk about what these poster-making kits are and how they work?

NC & NP: We all came up with a few simple icons that symbolize themes of the campaign—systemic racism, poverty, war economy (and militarism), and ecological destruction. The kits include those icons as well as colorful backgrounds, collage material, stamps and markers so that anyone can recombine and add to the imagery and issues in their own way.

Community Poster from workshop with Justin Poppe at Northeast Library.

All the elements have meaning: The colorful backgrounds were letterpress printed by curator/collaborator NoMüNoMül at the Globe studios at MICA—evoking the vivid street presence of Globe music posters for those of us that grew up in DC. Teen groups at the library helped research collage material showing images of protest in 2018. And we made stamps from related material in the Library collections—like the mother and child logo from 1968 Poor People’s Campaign brochures, and the logo of the National Black Environmental Justice Network, founded by Leroy “Damu” Smith, a famous DC peace activist who advocated for a Martin Luther King Jr. holiday in the 1980s and who was one of the leading voices connecting environmental issues to systemic oppression.

AH: Can you walk us through a workshop?

NC & NP: The artist leads off the workshop by sharing a bit about their practice and why she/he chose the theme of the poster they produced. Then it’s simple: participants choose a background, an icon, then collage, stamp, draw and write to add their own interpretation to the issues. Teens have made great posters. But it’s also so simple that kids can do it, then the parents join in and start talking. Finally, people take their original poster home after we scan it on the library copier and add the image to our archive so they can be saved and reproduced.

Ultimately, we’re interested in the workshop being a place where political education and cultural production collide and support one another. Our hope is that people walk away with a not just a poster, but an understanding of an often-overlooked history, and an understanding of how that history is connected to their own experiences today.

Hunger Wall Poster Project workshop led by Adrienne Gaither and Omolara McCallister at the Center for Inspired Teaching’s Interschool Seminar on gun violence, Photos by Olivia Weise.

AH: What has been the reaction to the these workshops?

NC & NP: The project just keeps growing. We’ve had people come back to more than one workshop; we’ve had teens stand up and educate us about issues in their community, we’ve had really quick interactions with school groups that go crazy with stamps for ten minutes and that’s OK too. Part of the point is that people can enter into this activity easily, learn something, and walk away with a piece of protest art. Also, the more people see what others produce the more we get invited to do our workshops in new spaces. The Library’s amazing outreach team is scaling the project by taking kits into the DC General Family Shelter (which is set to be closed before the end of 2018), into the DC Housing Authority and DC Parks and Recreation sites where they do important work all summer.

This is why the library is the People’s University of today. Honestly, Librarians work with everyone!

Librarian Maria Jones and Woodridge Library Teen Lounge workshop participants. Photo by Olivia Weise

AH: What do you hope people will do with the prints?

NC & NP: People can take them home with them, hang them up, wheat paste them somewhere—it’s really up to the participant. We have been giving away free posters — including the Justseeds Poor People’s Campaign original designs—and we add in prints from the community posters—these get as much of a reaction as the ones the artists made. We also have been doing installations around town.

And most importantly, there is the fact that we are creating a new Hunger Wall throughout the city in different ways. We’ve been invited to wheatpaste posters with teens on community walls. We gave Monolith some posters and he made a tribute to the Poor People’s Campaign with a big graffiti portrait of Dr. King at the Broccoli City festival. We had teens wheatpaste walls of posters and had 411 Collective reinterpret the original Hunger Wall message (which read “Hunger’s Wall: Tell it Like it Is”) in graffiti style bubble letters as a live painting event for DC’s Funk Parade in conjunction with DC Public Library’s Soul Tent installation space. Since that weekend was both DC’s beloved local music celebration and the 50th anniversary of the launch of the Poor People’s Campaign, it seemed perfect to launch these projects there. We’re working on a big poster exhibition for September where we can invite all the people who contributed back to see the project all together.

The amazing thing about posters—as you know—is that they go viral.

411 Collective Hunger Wall Poster Project live painting event and DC Public Library’s Soul Tent installation at D.C. Funk Parade. Photo by Victor Benitez.

Natalie Campbell and Nick Petr are curators working with the DC Public Library on 1968 anniversary programming throughout 2018. For more information on their project visit the DC library’s website: https://www.dclibrary.org/1968

Follow the project on Twitter #PeoplesUniversity or on Instagram @hungerwallposterproject and @soultentdc

Natalie Campbell is an independent curator, art historian, and project manager active in DC and New York, a Lecturer in the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) MFA Program in Curatorial Practice, and has been working with the DC Public Library Foundation on exhibitions and art programs since 2016.

Nicholas Petr holds an MFA in Curatorial Practice at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) and a BFA in General Sculptural Studies at MICA. He grew up in Baltimore and Southern Pennsylvania and has a background in industrial design, architecture, sculpture, and social activism. He is a co-founder, resident curator, and instructor of cultural studies at the Oak Hill Center for Education and Culture in Baltimore, a cultural center for learning, sharing, and transformative social movement building across race, class, gender and social difference. As the 2017-2018 DC Public Library + MICA Curatorial Fellow for the People’s University, Petr works with four librarians to mentor on the art of curation in an effort to benefit the local community. He also assists the team in mining library collections and developing programming related to the history and relevance of the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign today.

Thank you