culturalorganizing.org recently posted a review of my book A People’s Art History of the United States: 250 Years of Activist Art and Artists Working in Social Justice Movements. Here is the full text:

Review: A People’s Art History of the United States

Posted on October 18, 2014

By Nicolas Lampert

New York: The New Press, 2013. 345 pp. $35.00 (hardcover).

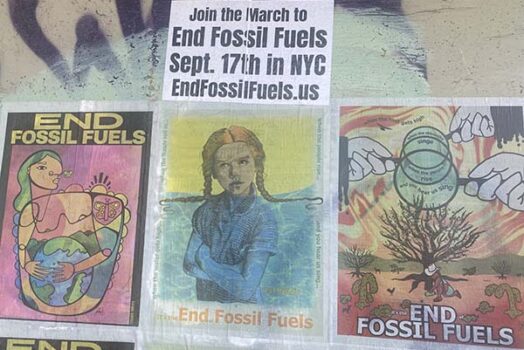

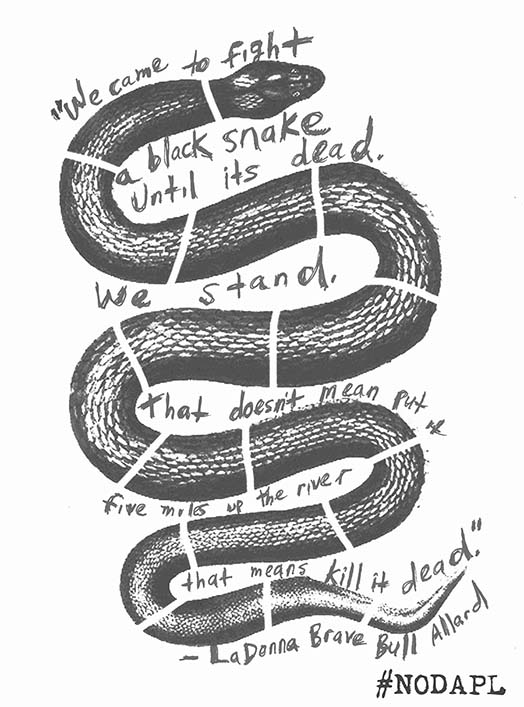

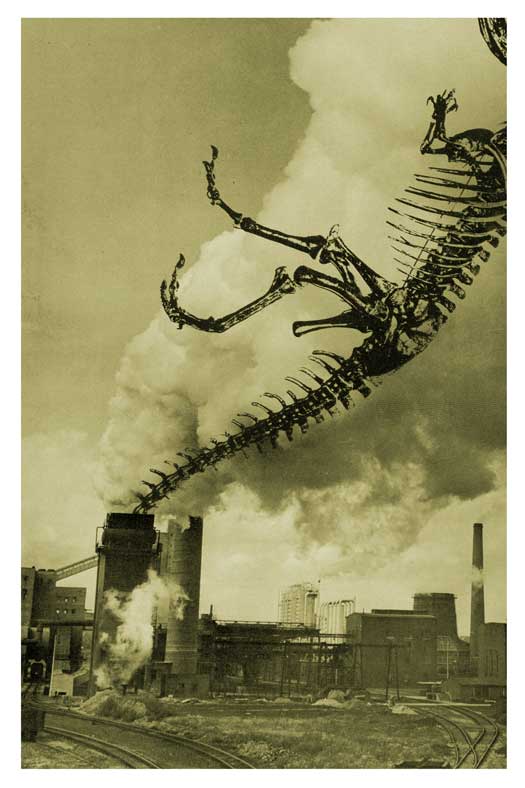

The newest in a long line of people’s histories inspired by the work of Howard Zinn, A People’s Art History of the United States by Nicolas Lampert uncovers the many ways that the visual arts have served as a space for political action and resistance throughout US history. With hundreds of images of political art from across the past five centuries, this book makes a compelling argument that art and politics — often seen as separate realms — have always been intimately and inextricably intertwined.

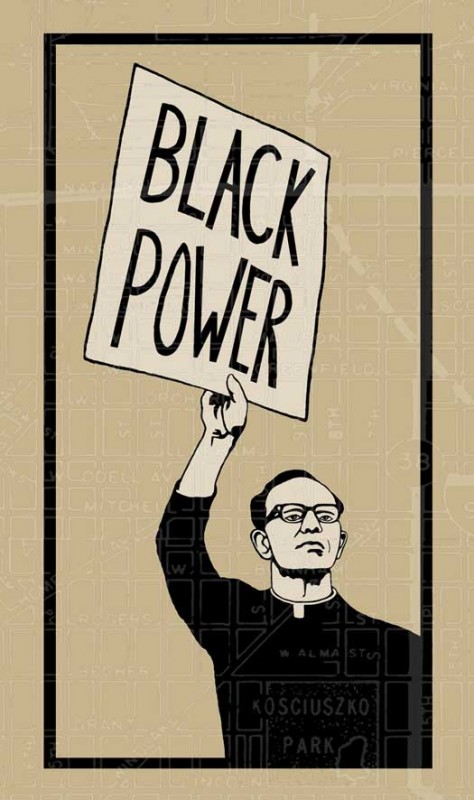

Despite the cover image, which brings to mind a framed work of art, this is not a story about political paintings hanging in museums. Instead, it is a story about how popular and public forms of art — from posters and photographs to cartoons and statues — have always been a part of civic and political life. When professional gallery artists do show up, they are likely to be organizing a union or protesting against the gallery system.

The book starts in an unexpected place, with what Lampert argues is the first art form in the New World to be partially shaped by European colonizers: the wampum belt. Made from beads constructed out of shells and strung together, wampum belts developed as an indigenous art form using European tools. In addition to their beauty, the belts were used as a medium for communication and record-keeping among tribes, and between native peoples and the colonizers, forming both a literal and metaphorical connection between the Americas and Europe.

Lampert covers a wide array of historical narratives in his book, many of which have received little attention in the literature on art and social movements.There are chapters on printed maps of slaved ships distributed by abolitionists, banners used by advocates for women’s suffrage, a battle over a civil war memorial featuring African American soldiers, up through the media antics of the Yes Men. While some of the artists — like Emory Douglas, Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party — are well known, many others were new to me, including thousands of unnamed participants in collective art pieces like the IWW-led Patterson Pageant.

At times it is difficult to tell whether this is a story about arts activism, or whether political art is being used to tell the story of the United States itself. In reality it is both, and that is one of its greatest strengths. In uncovering the story of the Workers Film and Photo League in the 1930s, or the role that photographer Jacom Riis played in the tenement reform movement, Lampert is both highlighting the political use of photography and film, and giving voice to lesser-known resistance movements.

Importantly, Lampert does not shy away from the complications and tensions inherent in this work. For example, he takes time to examine the way that Riis’s photographs of the horrors of tenement life reflected racist and anti-immigrant views, and how the Patterson Pageant led to tensions between organized workers and the Greenwich Village artists who sought to ally themselves with the movement. The book is less an ode to the power of using art to create change, and more a complex exploration of how the arts are always political, and have long been a part of struggles over justice — we just have to look in the right places.