This year, my son did not have to create a diorama of a California mission, like so many children in California schools used to do. Instead, the class studied the Native Peoples of the Bay Area, listened to interviews with elder Corrina Gould, watched the Ohlone Café chefs reclaiming and reimagining their ancestral foods, and created their own zines to share what they had learned with the adults.

I don’t remember what mission I covered in fourth grade. We probably did one, as did most California public schools. Somehow, it was all normalized, and for me, maybe even a question of pride, as a Latino immigrant and Catholic kid. Maybe my teacher in fourth grade thought there was better use of our time than making cardboard and popsicle stick models of idyllic missions that never existed like that.

Later, in architecture school, we spent long hours making complicated models of our imagined buildings. Those models were pure little objects, devoid of the human life that might inhabit those buildings, hiding the class and race and gender antagonisms that define buildings as social spaces, never asking how they would get built or whose interests they would serve. But those simple models could also be taken apart, interrogated, unearthing the deeper story, unfolding the layers of history in which they were situated. That was not, of course, the approach taught in architecture school.

As a parent, I now cringe at the thought of these little projects glorifying the California missions. It would be like asking kids in the South to make models glorifying slave plantations, or asking kids to model Japanese-American concentration camps, or more contemporary, Super-Max Prisons.

I imagine what a different kind of class exhibit of the missions could have been like, one that told the indigenous story, not the imagined and romanticized Spanish and Catholic myth designed by California legislators in the late 19thth Century to attract real estate speculation. Maybe some of the words and the atrocities might be too much for fourth graders to grapple with, maybe it would be a middle school or high school project.

I see each student showing their parents at the school’s open house the origins of occupied California as we know it today. As the parents walk between rows of little mission dioramas, each student explains their project. “Here’s ‘the Saint,’” says one, “Father Serra. Did you know he was trained under the Spanish Inquisition?” A parent asks what the good father doing, a little stick figure flailing about with what looks like a rope. “Oh, he’s whipping himself. He thought that would get him to heaven. And he and the other fathers didn’t think anything of whipping the Indians on their missions…”

The churches are elaborately decorated by the young artists, with little matchstick crosses. “All built with Indian slave labor,” a student explains. Some of the adjacent buildings don’t seem to have gotten much work, just plain upside-down cardboard boxes surrounding the church models. “Those are the monjeríos, windowless barracks where the priests kept all the Indian women over 8 years until they got married. I wanted to put in something to show how unclean they were and how bad they smelled, but the teacher thought that was too much…”

The parents walk on. “This was the first mission that Serra built, on Kameyaay land in San Diego in 1769. The Indians were supposed to come voluntarily to the missions, but once they were baptized, they couldn’t leave without permission. They were basically slaves, working for the priests building the missions and later building up the economy of the colonizers based on cattle ranching.”

A parent notices the nice little cemeteries with tiny toothpick crosses next to each church. There’s a hole cut into the base of each diorama, next to the graveyards. “Those are the mass graves,” a student answers. “Between diseases, unsanitary conditions, and overwork, few Indians lasted more than two years in the missions. Many were babies. And women.”

One of the dads points to the stick figures running toward the mission from the hills around it. “These are Kumeyaay resistance fighters, led by Zegotay, attacking at night in 1775 with about a thousand warriors. The Kameyaay soon realized that the Spanish had not come to visit or to exchange, as traders from other tribes had done for centuries, but to settle, to steal their land, and to destroy their livelihoods and way of life.” What’s the red crinkly paper in the roofs, the dad asks the creator of this diorama. “I tried to show the flames when the Kameyaay burned down all the mission buildings,” the student explains. “Here’s a group surrounding Padre Jayme, they filled him up with arrows.” A second student speaks up. “Over here is another mission, at San Juan Capistrano, where on the same day another 15 communities rose up to try to get the missionaries out.”

The dioramas are grouped on tables by geographic area, and the parents move on to the ones in Northern California. “Here’s Mission Dolores in San Francisco, on Ohlone land,” explains one youngster. “That’s Father Dante with the whip. And that’s a group of escaped novitiates, coming back to free their friends, led by Pomponio. His group was known as Los Insurgentes, the insurrectionists. They raided the missions for three years, from 1821 to 1824.” Another student points to the blue construction paper separating the diorama from the next one. “Over here on the water, that’s Marino and Quintino, a Coast Miwok chief and his lieutenant, on tule reed boats, crossing the Bay to mount a surprise attack on Mission San Rafael.”

The parents walk over to the next table. “Here’s Mission San Jose. That’s Father Gil in black, he was especially cruel to the women in the monjeríos. Up in the hills here, that’s Estanislaus gathering allies from Yokut tribes in the Central Valley in 1828.” Each student describes the resistance to each mission. “Over here is Santa Cruz Mission, and Cipriano leading his followers to join Estainslaus’ guerilla army in the mountains, and here’s Santa Clara Mission, and Yozcolo escaping the mission with his followers also to join Estanislaus. They were able to build a pan-Indian rebel alliance in the Sierra Foothills, turning back the Spanish over and over. They did that until Vallejo brought cannons and burned down the forest to get them out.” Like the US did in Viet Nam, one parent comments.

Another child speaks up. “We just told you the Spanishized names of the indigenous leaders, because it was the Spanish who wrote the histories. You might recognize some of the names as places we’re familiar with today, like Marin County and Stanislaus County, and San Quentin and Pomponio Beach, though few people really know that they were named after indigenous resistance fighters. But these warriors all had their own names, before the missionaries baptized them with Spanish names. Marino’s name was really Huicsume, Quintino was Tiguacse, and Pomponio was Lupugeyun.”

They are all men, points out one of the moms on the tour. What about the women? “Well,” one girl answers, “the histories were all written by men, by the Spanish padres and the soldiers. They didn’t think much of women. But in most native communities, decisions were never made without the women, even if the women didn’t lead the raiding parties. We do know one name,” and she points to the San Gabriel Mission. Six groups of Indians are shown approaching the mission buildings. “That’s Toypurina, a Tongva healer, leading six villages on a new moon attack on the missions in 1785. She wanted all the missions and soldiers gone from California. She was kinda like Joan of Arc, a young spiritual leader turned warrior, fighting off the invaders, and like Joan of Arc, she was later accused by her enemies of being a witch.”

There are a few dioramas without missions, even though this is the “California Missions” project. “This one’s a mission that never happened,” on student explains, showing the half-destroyed buildings in their diorama. “The missionaries wanted to push to the east, near the fork of the Colorado and Gila Rivers in 1781. The Quechans, allied with the Mojave, burned it to the ground, and killed over a hundred Spaniards. By this time in colonization, the Quechans had acquired horses and Spanish firearms, evening the odds a little. The Yuma Revolt closed off the Anza trail from the Spaniards for 41 years, from 1782 to 1823. The missionaries never came back.”

On another table are three more mission dioramas. “This was the site of the Great Chumash uprising of 1824: Santa Barbara, Santa Inés, and La Púrisima. After the rebellion, many of the rebels escaped the slavery of the missions through a pass in the mountains near Bakersfield. This diorama shows the settlement out past the tulares, the tule marshes, where they built their own villages and farms. They reestablished tribal life, but also incorporated new farming techniques they learned on the missions.” Another student points to a diorama showing canoes approaching some islands. “Others from the Chumash uprising escaped in tomol canoes, made from redwood tree planks, back to the Channel Islands on the Pacific.”

Those dioramas over there don’t look like missions, either, one parent points out. “That’s an haciendaof the Californios,” the student explains. “After Mexican independence, the new government promised to break up the missions and give the land back to the Indians. But the law stating that was supposed to happen, didn’t get to California till two years later. Kinda like Juneteenth in the American South, news traveled slow. By then, the former soldiers and colonizers had taken all of the land, and created big haciendas and cattle ranches for themselves. The Indians got nothing, except at least they were considered full citizens of Mexico. So, as they had before, many continued to raid the ranches that were built on their own stolen land. To the Californios, they were cattle thieves, but for the Indians, they were just trying to maintain a little of their traditional ways on what had always been their land, hunting where they could, sneaking in to gather what seed fields were left, or oak trees ready for acorn gathering, or raiding the cattle that destroyed their food sources.”

Another student speaks up. “Some historians say that by 1845 the Indian raids were on the verge of driving the Mexicans out, but by then there was starting to be a new wave of colonizers from other countries. And then the US invaded and gold was discovered, and in a couple of years California became a new US state. This was before the US Civil War. The new state was supposed to be a ‘free’ state, without slavery, but Indians were not considered citizens, and the new California government passed laws giving rewards for Indian scalps and allowing Indian children to become indentured servants, basically slaves, for white settlers.”

At the far end of the room is a diorama of a little makeshift village of wooden shacks. “Over here is Alisal, the alder grove, a village of survivors from many Bay Area tribes, Ohlone, Miwok and Yokuts, that came together near Pleasanton, starting around the 1830s. The landowners, first the Bernals and then the Hearsts, let them live there, and they were able to reclaim some of their traditions. They even took part in the Ghost Dance revival movement that energized many indigenous communities throughout the US in the 1890s. But they had no title to the land, and there wasn’t enough land to support the community as they had traditionally. People began moving out to find jobs. Only a few people were left by the time the village burned down, in 1914. Today many Indian communities trace their ancestors back to survival villages like these.”

The last diorama doesn’t show a mission at all, or even houses, but a round trellis structure built up against what looks like a freeway. The last student explains their project. “Many Indian communities associated with the missions were never able to get Federal recognition, which meant no land or other resources. It’s hard to survive as a community without a land base. But some communities are struggling to get land even without Federal recognition. This is the Lisjan Ohlone Arbor that was recently built by the Sogorea Te’ land trust in East Oakland as a gathering place for Bay Area Ohlone. Some people are rebuilding round houses for dances, and sweat lodges, where there haven’t been any for decades, and others are working to reclaim shell mounds that have been paved over to preserve them as sacred sites. The fight to reclaim land and space didn’t end with the missions, but it’s still going on, all around us…”

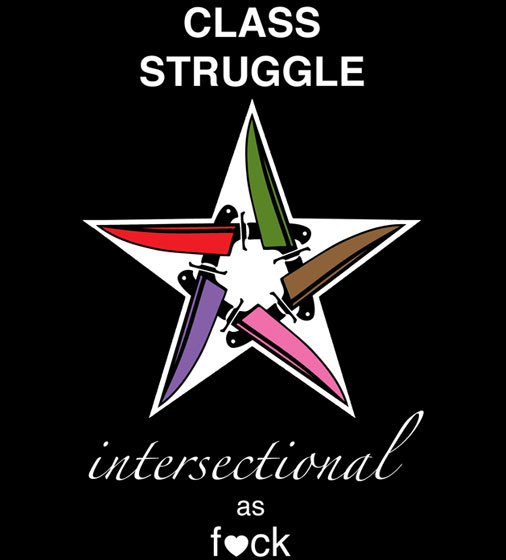

The parents, good liberals, nod their heads. But the students aren’t done. They gather at the front of the class, and the teacher sits down. “In this project, we learned how, in California, the missions were the first institution to take away Native People’s own land, all up and down the coast. And then the Californio’s divided Native land into big ranchos, extending into the Central Valley. And then the Americans came, and the gold rush, and they took all the land away up into the mountains. Even the beautiful national parks, like Yosemite, were created by removing all the Indians who lived there from their own land, so others could enjoy it as ‘nature’ without any people living in it. Indian people resisted and fought back every step of the way. And now all the land we have, where our houses sit, our office building and shopping malls and parks, and even where this school sits, is land that really belongs to the Indians. And so what are we going to do about that?”

The parents are silent for bit, not sure what to expect. “We’re just school students. We don’t have easy answers. But we think it’s something we’re going to have to confront as we grow up, like we’re going to have to confront climate change and so many other things. For answers we’re going to have to look to what Indigenous People are already asking for.” The parents sit, still silent and expectant.

The student who did the final diorama, of the Ohlone Arbor, is the last to speak. “In the East Bay, for example, Ohlone people are asking the broader community, who benefit from the land that was taken from them starting almost 250 years ago, to think about what they can give back for the use of that land. They’re calling it the Shuumi Land Tax. Things like that could be a start…”

San Francisco, January 2020

Sources: Natives of the Golden State: The California Indians, by Cahuilla elder and scholar Rupert Costo and Jeanette Henry Costo; Chief Marin: Leader, Rebel, and Legend, by Betty Goerke; A Cross of Thorns : The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions, by Elias Castillo; and The Indians of California, published by Time-Life. More info on Alisal can be found here: http://www.peraltahacienda.org/PH_allalbums/exhibitpages/pdfs/nativeamericanstorybook.pdf. Thank you to Mari for introducing me to Toypurina’s story. For more information on the Shuumi Land tax, see https://sogoreate-landtrust.com/shuumi-land-tax/. Image of Mission Dolores diorama downloaded from http://slicesofamerica.com/the-mission-san-francisco/