It takes a lot to regenerate my interest in street art. Often it takes being introduced to someones work who is pushing the genre outside of its boundaries. This is the case with Chip Thomas who I first learned about through the enthusiasm that Justseeds member Chris Stain shared for his work. He interviewed him on the Justseeds blog in 2010 and I was immediately struck by his work and his story. Chris also said something to me in passing about Chip that stuck with me. “When you hang out with Chip Thomas good things happen.”

Chip is not your “typical” street artist. He is a doctor in his fifties who moved to the Navajo Nation in 1987 to work for the Indian Health Services. He also is a photographer who is a relative newcomer to street art. In the mid 2000s he traveled to Brazil and was inspired by the street art scene. He was also inspired by the work of JR. So he decided to put up his own photos around his community – the Navajo reservation that extends for hundreds of miles throughout the northeast portion of Arizona. He put up large wheatpasted images of photographs that he had taken of community members – some of whom were his patients at the health clinic. His selected images and the vibe of the work was nearly always overwhelmingly positive. Positive images of the community to help project a positive message to the Navajo and those who visit the reservation from the outside. That said, Thomas does not avoid the more pressing issues that the Navajo face: issues of fossil fuel extraction, environmental destruction, and so forth – but his overall message still remains hopeful. Equally so, many of his images reflect the strength of the Navajo people and their perseverance – Native pride, traditions, and history.

text on the arm reads “Native Pride”

Attempting to label Thomas as a street artist is all to limiting. He is more akin to a community artist – one who employs photography, text, and graffiti to communicate messages that reflects the pulse of his community where he operates as both an insider and an outsider to the place that he calls home. His work is in dialog with the community. Moreover, he curates one of the most interesting “street art” projects in North America – the Painted Desert Project – where he personally invites street artists that he admires to create pieces on the reservation. These are not hit-and-run works of art where the artist puts up whatever he or she wants. They are instead carefully considered works of public art where Thomas discusses with the invited artist what will and what-will-not fly in the Navajo community in terms of content and imagery.

image: (left) ROA (right) Chip Thomas

mural by Alexis Diaz

mural by Narindrankura Nadine and Thomas Greyeyer

Thomas related to me (and a packed lecture hall at UWM) that the Navajo community has had enough bad news over centuries of colonization. Negative images only reinforce the worst elements of past and present history. He also noted that some images would not go over well with the Navajo people. Images of death (dead animals) for example would be frowned upon. Thus, the first step in his work and the pieces that he curates is to demonstrate cultural sensitivity and a respect towards the Navajo people and their history.

The location for the work is also significant. Thomas explained that many of the surfaces that he and others paste images upon are often on the sides of wooden market stands were the Navajo sell their crafts to the stream of tourists that pass by, often on route to Monument Valley. This location is not arbitrary. Thomas often hits these spaces because community members appreciate the attention that the images bring. It makes tourists stop for a closer look – a visit that might lead to more tourist dollars being spent at their stand.

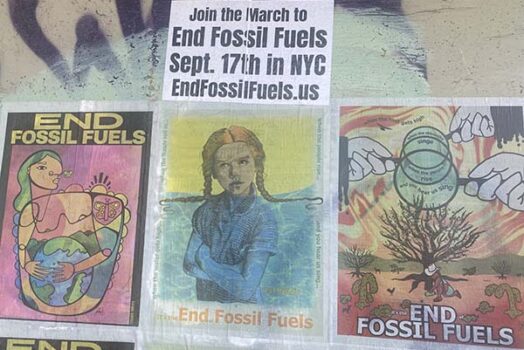

Moreover, his work speaks intelligently to the issues that the community is already talking about: the high rates of diabetes, domestic violence, and suicide rates. Various images address fossil fuel extraction and the economic and political issues at stake: the fact that the Navajo should be some of the wealthiest people in North America if you look at all the value of all the coal and uranium that is extracted from their land. Yet, instead the vast majority of the Navajo live in poverty due to rigged treaties and economic exploitation that has worked against the majority of the community. Other images go a step forward and critique the rising C02 levels and the global environmental crisis due to the mining and the burning of fossil fuels, including on the Navajo reservation.

Thomas explained this deeper meaning behind his art and curatorial practice during his October 2nd lecture at UWM as part of the Artists’ Now lecture series. His delivery reflected a humble person who did not boast about his work, nor did he put a primary importance on himself. He simply told stories. His honesty was refreshing. He talked about being a doctor and an artist. He talked about being an African American man in his fifties living on the Navajo reservation. He talked about photography and street art. He talked about a bike trip that he did across Africa – from the very top of Africa to the the very bottom of the continent. Most students listened with their jaws dropped. The next day when Thomas visited my printmaking class of twenty students the first student to ask him a question simply asked: “How did you become so awesome?” In the weeks that followed students from another class – a theory class – wrote a critical reflection – words that speak volumes about his practice. Here are a number of choice quotes that demonstrate how the lecture hall audience responded to his work and his presentation style:

“Chip Thomas did not do the art to make himself better, but to help the people realize how great they already were.”

“The wonders of the world lay within a community. Everybody has a story to tell. Chip Thomas captures these moments by spreading these stories and embedding them in the landscapes they play in. He not only is a visionary, but he listens to the sounds which surround him. His modest look on his own encounters in life shows how passionate he is about his work. Doctor by day, artist by night, he manages to balance the two forms of art, but yet inspires all who he has encountered both physically and spiritually.”

“Instead of just being an observer on the outside he really immerses himself in the community. He is not only working with a community to raise awareness, but also celebrating a culture through his street art.”

“I think his role as a physician and an artist are very similar. He is always looking out for the greater good of others… My favorite thing that he said was how he chose his images in such a way as to bring happiness to those who see them.”

“It’s not just that it’s giant photography wheat-pasted on the sides of dilapidated roadside stands though, it’s the content, and the location that speaks volumes and gains quick intrigue. Much like the earlier photographers he referenced as influences, Eugene Smith and Eugene Richards and what they captured … harsh realities for some that most of us don’t see and framed in a way we wouldn’t normally look at it. The Navajo people, who have suffered on a severe magnitude, in a world completely different from the American one that envelops them is what interested me the most. He touched on the alarming rate of diabetes the suicide among youth and assaults, but his artwork is the furthest from dwelling on these facts.”

“Chip is a saint in my eyes. Not only is he an MD and spends a lot of his time helping others, but his artwork reflects the people around him. He uses his artwork to give a voice to others.”

“What I loved the most was his black and white photography. Each photograph captured different emotions, yet each were just as powerful. Using the power of that photography, he also sought a way to get involved in the community by enlarging and putting them on buildings. One could argue that he is actually building community by gathering people together: tourists, economic growth, etc.”

“His imagery is typically placed along the roadside for passerby’s to see. These images are always site specific so they’re scale and rhythms are integrated beautifully to the spaces and the landscapes they live in. Most of his imagery is posted on decaying architecture. The architecture without these images probably wouldn’t elicit a second look. But once the imagery is positioned something magical happens.”

“There is room for the artist’s hand to play a role anywhere. If we can take a note from the work Chip Thomas is doing, we can follow that lead and do something positive wherever we may be.”

A final quote “It would be interesting to see what his work would be like if he moved to a different community and started doing work in a different place” resonated for me for Thomas did create new work when he visited Milwaukee. Prior to his visit Thomas, along with myself, were in touch with Andrea Avery who is the community arts coordinator at the John Michael Kohler Art Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin – which is forty-five miles north of Milwaukee. Avery had organized an ambitious and important community art project called “The Sheboygan Project” where a roster of a dozen or so street artists – the majority of whom were from outside of Wisconsin – traveled to Sheboygan over the course of two years to put up work on various walls throughout the city. The project was extraordinary for Avery was activating the city with art and breaking down the biases that many community members likely held towards street art. In truth, the work that she selected was much more akin to public art and contemporary painting than “street art,” and the community was very much involved in the process. Walls were temporarily lent to artists by the city or by business owners and many of the artists spent days, if not weeks, in dialogue, or in collaboration with the community to create their final work. The last two artists to travel to Sheboygan were myself and Chip Thomas.

Our late arrival and limited time in the city presented obstacles for both ourselves and Avery. In the case of Chip Thomas he was visiting the city for the first time. In contrast, the power of his work on the Navajo reservation is the sensitivity that he brings to it: his knowledge of the people, culture, history, and the landscape. He also carefully scouts out each location and his work is designed to fit with the architecture that he selects – be it a empty billboard, a roadside stand, or an abandoned house. Thus, the power of the work is often the story that the architecture and the landscape conveys in connection with the image that he selects for that particular location. In Sheboygan he did not have these key components of his practice in place.

However, he brought a camera to Wisconsin and an archive of images so that he could create new work on the spot. And once here, he became drawn to the subject of agriculture that is so prevalent in rural Wisconsin. In the end, he decided to photograph a clenched hand – my hand to be exact – holding a stock of corn as a symbol of the struggle that family farmers face in a landscape dominated by corporate agriculture. And prior to the install day Thomas enlarged his images on an Epson large format printer at UWM thanks to the help of Photo Prof Joseph Mougel who graciously assisted with the technical end of the collaboration.

When Thomas and I arrived in Sheboygan I was struck by how much the project differentiated from his working methods in Arizona. He was seeing the city for the first time so his process relied on chance – much like a street artist going out with a can of spray paint or images to wheatpaste under the cover of darkness where quick decisions are made on the fly.

These factors aside, Thomas is resourceful and his images are so graphically powerful that they would look good on just about anything they were adhered to. And with the help of Avery, Thomas located an interesting spot next to a walking trail and a river on a stone-block wall underneath a bridge where the bond paper could follow the contours of the stone to make an aesthetically-pleasing image. Four hours later the piece was done, but for me, something was lacking. The Sheboygan work did not hit me on a gut level like the work that was situated on the Navajo reservation – or for that matter, previous pieces on the side of a building in Albuquerque and on various walls in Tucson. In these examples his work outside of his home base were all successful due to the scale of the images, the juxtapositions, the carefully considered use of architecture, and the time allotted for him to get to know the location.

This is not a knock on his Sheboygan work. It is just an observation that many of us – not all – create our best work in the places that we are most familiar with. The Sheboygan Project was a great opportunity for artists to push themselves outside of their comfort zones. If anything it reinforced the community aspect element of his work on the reservation. To me, his images on the reservation read as a collaborative form of story telling. It is as if two voices are speaking: the artists voice and the voice of the person or the people depicted. Both are grounded. These images hold the power of place and the power of history. One cannot separate his images from the Navajo people and their culture and history. And one cannot separate these images from the reservation, the majestic desert landscape, the colors of the landscape, and the brilliant sky that frames his installations.

Additionally his work on the reservation remains so striking because it is so atypical in the world of street and contemporary art. Street art has become so prevalent in urban areas over the past four decades that it has lost much of its luster – atleast for me. It has become normalized. Yet Thomas takes us – his viewers (particularly those of us who see his images On-Line) to somewhere new – a landscape and a culture that many of us are completely foreign to and one that we attach our own nostalgia to. Thus, Thomas acts as a guide to the outsiders – both the tourists who drive by and those who pass by the images on the Internet. He too serves as a guide to himself: using art to better understand his community and his place in it.

In wrapping up my reflections of his visit to Milwaukee – one in which I initially thought would be a paragraph of two and one that could be re-titled “An Ode to Chip Thomas” – Thomas left me with more surprises in store. During his five-day visit we would walk my one-year old puppy – Lola – to a spot under a bridge to wear her out with a tennis ball. She is (we believe) part pit, boxer, and Australian Cattle dog and she goes full speed from about 8am to 10pm, and exhausting her with exercise is key to any type of stability in the home. On one such walk Chip brought along his camera and took some unbelievable black-and-white action shots of my 45-pound canine flying through the air with a look of pure glee.

However, that was just a preview of what was to come. Thomas surprised me yet again this week when he emailed me photos that documented his latest work on the Navajo reservation: images of a silhouetted Lola wheatpasted on the side of a falling down building near the side of a road – proving his versatility as an artist once again. I have no idea how these images communicate to the Navajo or the tourists who drive past them, but I know how they communicate to me. They fill me with pride.

To see more work by Chip Thomas, click here.

To see the Painted Desert Project, click here.

To watch a video of his UWM lecture on 10/2/13, click here.