I like to think I’ve been able to craft a life where I can do the things I love or that I think need doing. Sometimes I’m making art, sometimes writing poetry, sometimes facilitating collective processes with tenants, sometimes teaching about housing policy or design, sometimes building things, often parenting and cooking and trying to keep plants alive.

But as we watch the news from Palestine, fifteen months of genocide now, I feel an increasing cognitive disconnect between my work here in the heart of Empire and the utter destruction unfolding in Gaza. Israel’s genocidal attack has destroyed over two-thirds of the buildings in Gaza, an entire infrastructure, at least 230,000 homes gone. The scale of destruction is always in the back of my mind, as I do my small part to help keep people housed, in dignity and stability, and to build the neighborhoods that support our beloved communities. The destruction continues, but we carry on, what else can we do?

A year and a half ago my colleague Peter and I left the Council of Community Housing Organizations (CCHO) after 11 years as co-directors, to make room for a new generation of board members and staff leadership. At the same time as I was leaving a steady day job, our family was facing an eviction. With the help of tenant and community organizations and the laws and programs we had passed over the years, we managed to stay in in SF. I’ve been able to focus more on art and writing and teaching, but I can’t seem to entirely leave the housing work. This year I had the honor of working with the residents at two amazing housing developments to envision the future of their communities, and I had the opportunity to advance what I think will be some important social housing tools for San Francisco, if we survive the next four years.

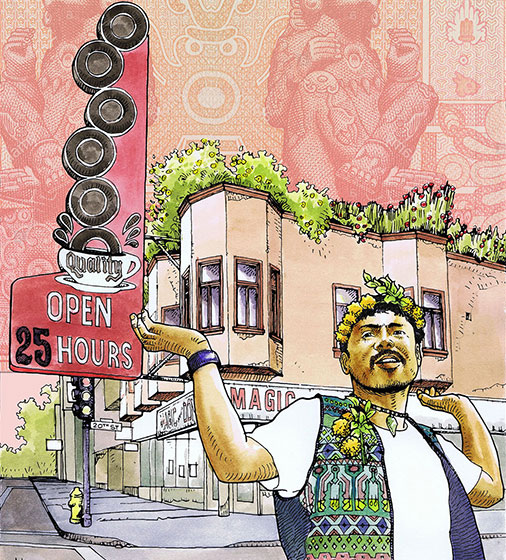

I was invited by residents of two different communities to engage their members in fruitful community visioning processes. The two developments share similarities: both built in the early 1960s as part of the Western Addition Redevelopment, they are both multiracial community pillars. In the style of the 1960s, they consist of 3-story and 4-story “walk-up” buildings, with large family-sized units, organized around large green tree-lined courtyards – a luxury compared to contemporary multifamily developments. The 60-year-old building complexes are facing the physical challenges of projects of that era: deferred maintenance, a need for new roofs, dry-rot repair, and plumbing and structural upgrades, and a need for accessibility improvements to allow their residents to age in place gracefully. But their histories are also very different.

Midtown Park is emblematic both of the structural racism and disempowerment built into inner city development, and the power of resident organizing to resist and to embody self-determination. In 1962, as the Black and Japanese American homes were being razed by the city’s urban renewal bulldozers, a private developer sold “Midtown Park” as a housing cooperative with the marketing slogan “own your own.” When almost half of the 140 units had been sold, the developer reneged on the promise, turning the development into a rental property (with the approval of HUD), and the original buyers lost most of their down payments. Shortly thereafter, the developer defaulted on their loan, while the parent company continued to reap wealth throughout the Bay Area for decades. The City ended up with the property, both the land and the mortgage. The residents fought for control of their community, and in 1968 the City relented by giving the residents control of the complex, including the responsibility to pay back the loan, but not the land. Thus the residents ended up with all the risk but none of the assets. In 2014, once the loan was repaid, the City took back total control of the property and handed it over to a nonprofit developer. For whatever good intentions the nonprofit may have had, the top-down approach, new income certifications, rent increases to match “AMIs,” and plans to demolish two of the buildings in order to create smaller elevator-served senior units, caused a rebellion. Midtown residents led the longest rent strike in SF history, and the developer ultimately fled. In 2021, newly-elected Supervisor Dean Preston made good on his promise to bring Midtown Park under the City’s rent control ordinance. This victory meant a renewed sense of stability for the tenants, but it was clear the City had no plan for how to care for the building under their control, nor a plan to respond to the residents’ demands for greater self-determination.

St. Francis Square, on the other hand, was a 300-unit development created by the multiracial longshore union, the ILWU, to build housing for its members and other working people. Like the labor-backed cooperatives of New York City from the 1930s, St. Francis Square was a limited-equity cooperative from the start – meaning that while residents owned a share in their property, the share prices had to remain affordable to future generations. Recruitment was intentionally carried out so that the housing complex reflected the racial diversity of the neighborhood. By the early 2000s, however, as residents retired, the members themselves voted to “go market,” doing away with the resale restrictions. While the values of shares went up, members kept monthly carrying charges affordable. Unlike Midtown, they are the sole decision makers for their own development – within the constraints imposed by the banks, the government, and entropy, of course. Now, in 2024, like Midtown Park, they are having to deal with the fact that their buildings are aging and in need of major (and expensive) renovation.

Capitalism always leads with the redevelopment/urban renewal model: tear down and demolish the old, evict and displace, and start over with new construction (usually with smaller units, less open space, and taller buildings), with each cycle reaping new profits for the investors, the developers, the builders, and all the systems that surround them.

Residents begin with what needs to be preserved, what is sacred and beloved of their community, and what physical structures support these values. With that as a starting point, residents can then address what needs to be changed or transformed to further support those values. This was the approach I learned from my mentors in architecture school in the 90s: Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, Sim Van Der Ryn, and Randy Hester. Could we maintain the squares and courtyards that were the heart of complexes, the greenery, the large sunny units, and the close-knit community, while addressing the accessibility and sustainability strategies that the 60-year-old developments required? How much would it cost, and how would it be financed?

At Midtown I worked with my old colleague from Asian Neighborhood Design, Steve Suzuki, to develop an estimate for the work required. The City had allocated only enough funds for the minimum structural and systems work needed, and only for one of the six buildings. We calculated the additional cost to preserve and improve the buildings in order to address the health and dignified lives of the people – elevators and universal accessibility design – which came out to spare change for the half-billion-dollar housing agency. With the City’s recently completed “Reparations Task Force” report, this could be the first real proof that the City was serious about addressing the historic harms done by urban renewal to the African American community of the Western Addition. The residents’ plan looked at all six buildings in the complex, addressing chronic operating income shortages, and what an understanding of respect for resident leadership could look like. Now, with a new Mayor and Supervisor, the people will see if the new electeds are ready to do right by Midtown’s residents.

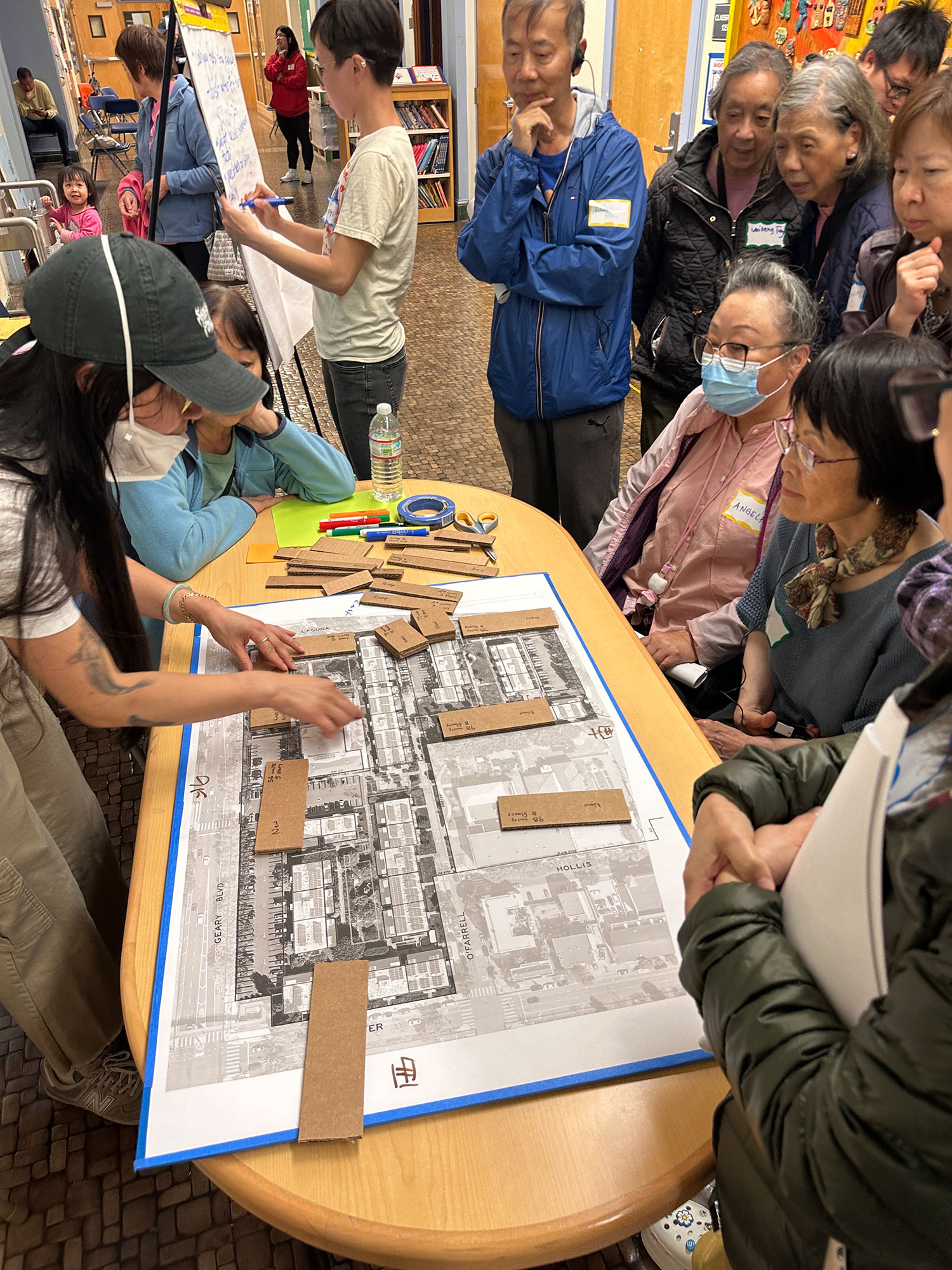

At St. Francis I recruited organizers, translators, and young architects to facilitate design workshops to imagine different futures for the complex. No developers or city agencies were in the room to influence the outcome, just the residents and their values, their dreams and aspirations. Only after residents designed their own visions – ranging from preserving most of the existing complex, to a design for all new buildings arranged around the beloved green squares — did the coop leaders bring in a development consultant to run the numbers. It is always refreshing to get a dose of reality from developers – different from the “pro-housing” boosters who are only concerned with pushing their libertarian ideologies. The financial study told us that an approach that favors preservation and rehab with a small amount of infill development to bring in income, is what would make the most economic sense.

Both of these are long-term processes, that will require resilience and fortitude from residents, to not be conned by either city agencies or developers with their own agendas, but rather to approach these entities from positions of power, of knowing their own values and visions. And achieving their visions will depend on long-term internal organizing by the residents themselves.

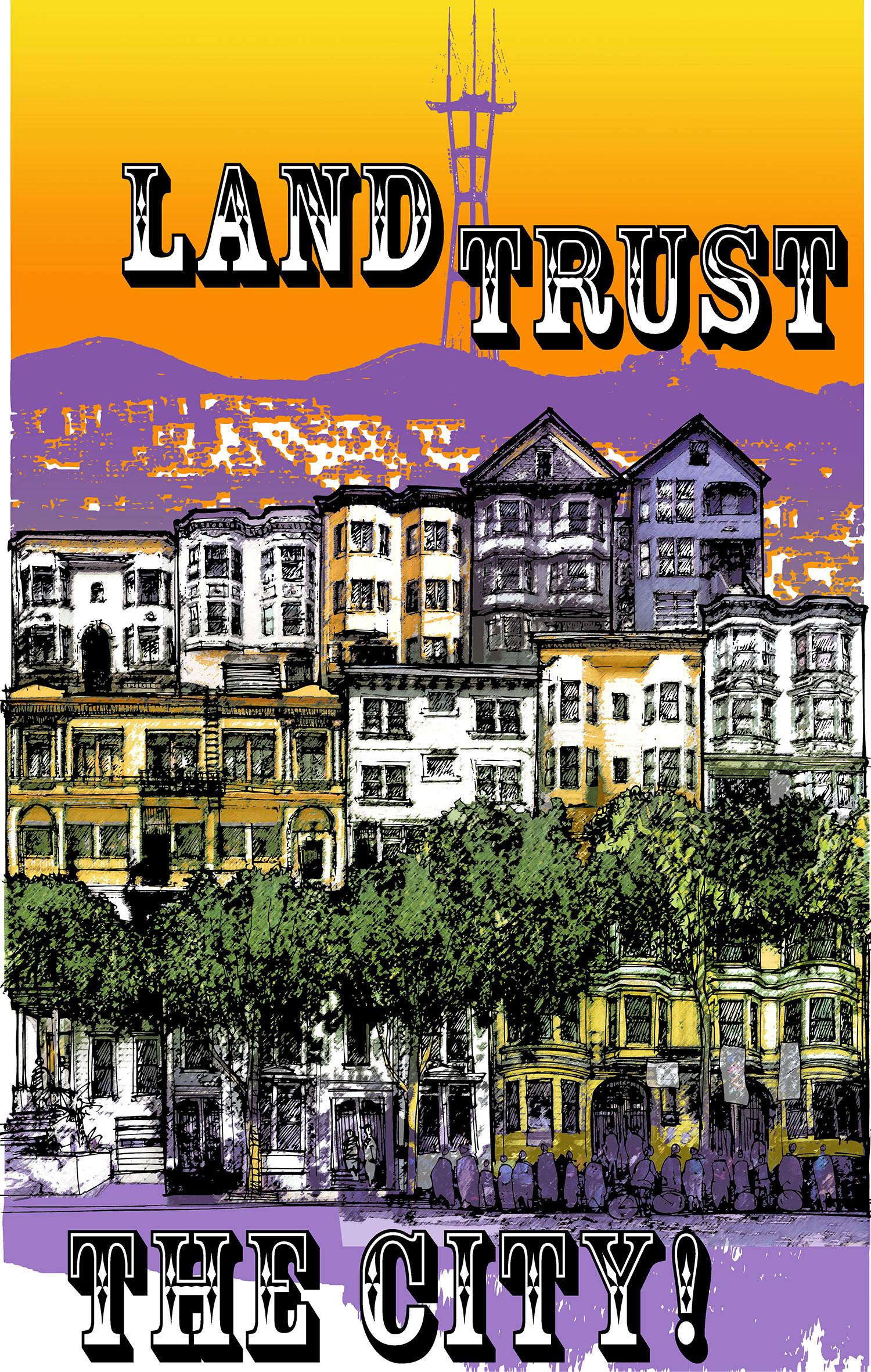

Part of the joy of this housing work is being able to support tenants and coop members directly, but also to be able to work on the wonkie policy and organizational and financing tools that they can use. Taking a step back, I also had the opportunity to advance the social housing agenda that has been an integral part of my work since my days with CCHO. In 2023 I helped to develop a business plan for a municipal public bank for San Francisco. This work led to a project with the SF Chronicle, to envision new financing approaches to social housing that could be affordable to public and nonprofit and arts workers – the broad swath of people like my family and friends who were not poor enough to qualify for low-income housing, and not wealthy enough to afford market-rate housing in the city. I pulled together a bunch of people I knew from the housing world – an affordable developer, a market-rate developer, a banker, a building trades organizer, and a socialist tenant rights advocate – to not just think through some cool ideas, but to show how we needed to work together to acheive it. We presented our ideas on a panel with the Mayor of San Francisco before an audience of 200 people – but she only wanted to tout her neoliberal deregulation talking points. Then, in 2024, outgoing Board president Aaron Peskin took on the idea, and we brought the team back together to hack through the details. The financing for workforce housing is now part of the City’s tools to make broad social housing a reality – and it may be one of the few approaches that actually starts building anything of consequence in the city over the next few years.

While at the national stage the country flounders ever closer to fascism, and the “rational” politicians remain mired in neoliberal platitudes, and genocide continues unabated in Gaza, organizers at the grassroots continue to work for new forms of self-determination, and to enact the tools needed to make that happen. And they will do so in Palestine as well. I feel privileged to be able to be part of that here, in whatever small way I’ve been able to contribute, whether it’s through creating art for the movement, reflecting through poetry, or working directly with tenants and coop members to give voice to their visions.

It will only get harder in 2025, but never more important.

Beautiful article Fernando! Well written and vitally informative. Thank you!