Dallas-based printmaker Viktor Ortix traveled to Standing Rock in September and then in early November where he stayed at the Oceti Sakowin camp for six weeks. He spent the majority of his time screenprinting patches in the art tent that water protectors wore on the frontlines during direct actions. Our conversation focuses on the role of the art tent at Oceti Sakowin and his experiences on the bridge on November 20th when police attacked peaceful demonstrators.

Viktor Ortix interview by Nicolas Lampert on December 29, 2016 (approximately three weeks prior to Trump taking office.)

NL: When did you first travel to Standing Rock?

VO: I first traveled there in the second week of September and was there for about four days. I went back to Texas and then went back on election day. On route we got pulled over by South Dakota police officers who planted drugs on us. We got out of that, luckily. We found what they stashed on us and got rid of it. Then got to Standing Rock on election day.

NL: Tell us what inspired you to head to Standing Rock?

VO: I had seen news of it on my Facebook feed in June and had been keeping up with it. Posting every day. Finally, I thought, I need to see it for myself: I need to know the facts, need to know the truth. So, just organized a way to get up there, get my eyes on the whole experience.

NL: What were your first impressions when you first arrived?

VO: It’s tough to put into words. (long pause). Breathtaking. Literally. I was in awe when I first saw Flag Road – seeing all the flags from all the Nations. Just the idea that over two hundred tribes at that time had touched the soil. That all these Nations had come together, to say no, to stand up, and to stand with each other. That was pretty breathtaking just to see the road – all the flags, and all these Nations had come together.

NL: Did you go there with the goal to work in the art tent and to lend your talents as an artist? Or did that occur more by happenstance?

VO: First time I went was to drop off supplies and see what was going on and see how I could help. The second time I went I took some screen clamps and a couple of screens. I was ready to work wherever I could. I didn’t even know there was an art tent until someone told me. Then, I just made my way that way and was there every day since.

NL: So, you were primarily at the art tent during your second stay at the Oceti Sakowin camp?

VO: Yeah. I was in the art tent for every day for about a month and a half.

NL: Essentially seven days a week?

VO: Yeah, just about. There were a couple of days that I would have to take off to rest my body, go out to some direct actions, or just volunteer to be of other use at the camp.

NL: What was the primary purpose of the art tent? What were the activities, what was being produced?

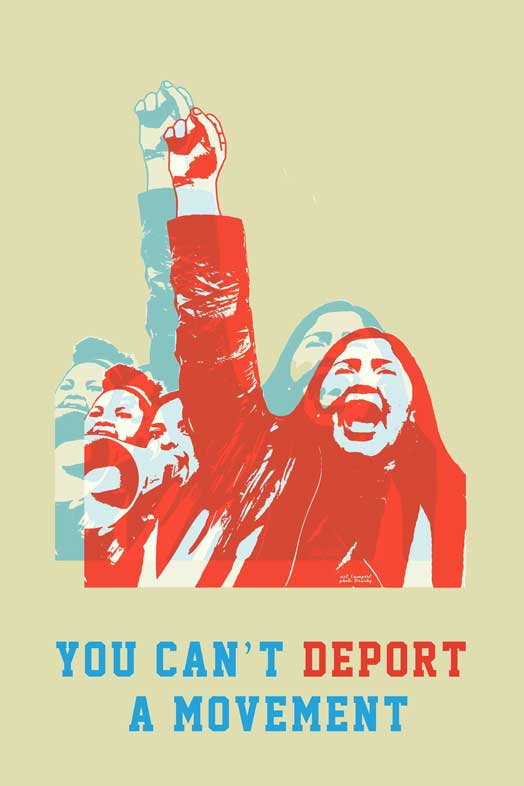

VO: The primary mode of production was banner making and screenprinting patches for front liners – those who went out on the direct actions. The primary focus – from my understanding – was to bring the art to the people, and to generate an image, or some kind of idea, into actuality. To visualize what solidarity looks like. Something that we can all stand behind. Something we can all be inspired by.

NL: Were you mostly painting banners or were you screenprinting?

VO: I was primarily screenprinting the patches. I was also printing t-shirts, and it was interesting because after days of printing t-shirts on a low table that nearly broke my back, I sketched up a design for a more practical table and gave it to someone, and they came back with it built!

NL: So back up. What happened?

VO: I sketched out an idea and a request for some wood so that I could build the table and I came back from lunch and it was pretty much built.

NL: That is amazing. Who built it?

VO: People from the construction crew who were building the water house.

NL: So, to segue to the screenprinting itself, could you talk about the screenprinting on jackets and sweatshirts. I know this differed from the patch productions. There was a time from noon to two o’clock every day when anyone in the camp could come to the art tent and get images screenprinted on their t-shirt or sweatshirt. Could you talk about how people responded to this?

VO: Sure. Just to see lines of one hundred to two hundred to three hundred people and having community hours for people to get images printed for them, you could just see the morale change. It didn’t matter if you were Native or non-Native, people just came together: we are in this together, we are all wearing the same message. So, just to see the morale change and everybody’s reaction, the spirit just got even higher. And this from prints – ones that had so much meaning. And now that everybody has it on them it was like we are now part of the same tribe.

NL: Did that change your thinking about the role of the artist at the camp?

VO: Yeah, actually. As an artist I kind of stepped out and said, okay, I am here to print and to produce and give back my skills to the people. But to see the reaction everybody was giving us for the art that we were creating, I didn’t realize that art had such an impact and a presence within a movement itself.

NL: What images were being screened and could you share insight on how images were selected? Were new images being made on site, or were people bringing screens with images that they had already designed?

VO: So, when I started in the art tent there were a few images that had already been dropped off – a few screens to make patches. Then I brought a few screens, and an artist from New Mexico brought a few screens. Some artists from California came in and they dropped some screens off and then some from Wisconsin, as well as artists from Detroit. So, these screens were coming in from all over the country.

NL: Was there a process on deciding upon which image would be printed? Did they have to be approved first?

VO: Yeah. IP3 approved which images we could or couldn’t use. Once images were approved, we would decide to print a series one day and rotate in another set of approved images the next day. Once we got into the flow for production for the patches we figured it was a lot faster if we could do one image all day at a single color or a flood roll.

NL: Explain what IP3 is to those who might know.

VO: IP3 is the Indigenous Peoples Power Project. They go around teaching and training Natives how to do direct non-violent action, how to organize, how to use art, how to use non-violent direct action.

NL: And they were the ones who approved which images were being circulated?

VO: Yes.

NL: On a technical side the art tent was set up in a location that had not been a studio prior. Did you ever have any problems at the art tent running short of supplies or lacking certain supplies that you were accustomed to?

VO: Yeah. At first we had limited amounts of inks. And once the temperature starting dropping it was hard for us to keep anything dry due to the humidity and just the cold. But as we began building up, and we starting becoming more of a factory – we got a variety of inks and we became more of a production line: we had runners [hanging up the prints], we had people loading fabric, but at the beginning it was just four squeegees, and maybe five screens.

NL: Were more people bringing in new art supplies as they traveled to Standing Rock?

VO: Yeah, and people were donating funds for more ink and fabric. I think we bought all the safety pins in Bismarck.

NL: Regarding the patches, I know they were primarily produced and given out for free to those doing the non-violent direct action, but were some also sold to those who stopped by the art tent to raise funds to re-stock the art tent supplies?

VO: I think initially we had one day where we just took donations for the patches and with that money we were able to restock our entire supplies of inks. After that we focused on giving all the patches to those on the front lines. Natives, the elderly, and children would also get free patches always.

NL: What supplies did you wish you had there? Or, in other words, what was the most pressing need at the art tent?

VO: Lack of heat was the biggest issue because it slowed down the drying time of the patches. We ended up making another tent that had a wood stove so that we could use heat to help cure the ink on the patches. We set up a bunch of [clothes] lines and once we started production we would have a runner take the patches in there – an entire tent full of hundreds and hundreds of patches just drying.

NL: Were you able to burn screens at the camp?

VO: No, not at all. Melanie [Cervantes] – I believe – donated some emulsion and we had some blank screens there. I coated them and tried to burn them but the environment was too much. It was a challenge to get the exposure right. It was just too challenging.

NL: And how would you wash out screens?

VO: (laughs) A gallon jug with some water in it – pouring it on the screen, scrubbing it, pouring it, and scrubbing it. A hose would have been nice.

NL: Tell us how the tent was led? Was it led by one person from IPS [Indigenous Peoples Power Project]? Or was someone put in charge for a week or two? Or longer?

VO: There was a production manager/coordinator that was there. She was from Alaska. Everything would come from her. Every morning, or the night before, she would give us the briefing about what we had to do, what we were painting, information about an action that we had to prepare for, so we would just crank the work out. I remember one day we worked about eighteen hours just producing patches for the vets. I think we produced over a thousand patches that day.

NL: That is incredible. During the six weeks that you were there could you give an estimate on how many patches were printed at the art tent?

VO: I am thinking it had to be around ten thousand-plus.

NL: All on muslin fabric?

VO: (laughs) Actually, we ran through that pretty fast and we wound up printing on bed sheets for some of them.

NL: Shifting gears. You were at Standing Rock on Sunday, November 20th when the police deployed water cannons, tear gas, rubber bullets, and concussion grenades on peaceful demonstrators. Can you walk us through your experience when you went to the bridge?

VO: Yeah. I was about to eat dinner and I heard a bunch of people yelling that people were getting shot at with rubber bullets, and being maced and attacked, so we ran out there to see if we could give protection and support for those who were out there. As soon as we ran up onto the bridge it was a war zone. Canisters just going off, flash grenades, and tear gas. Seeing people falling down from getting shot by rubber bullets. And just holding the line. At first I thought they were trying to raid the camp again. But seeing that people were just standing there, literally standing there and getting attacked, it kind of blew me away that anybody would attack someone just for standing. But I stood my ground and stood there for as long as I could.

NL: How close were you to the barbwire?

VO: I made it all the way to the front. That’s when I got pepper sprayed.

NL: What type of protection did you have? Goggles? Or had you come straight from dinner?

VO: I came straight from dinner and all I had was a jacket and a bandana, so I got up there and got an eye full of mace and fell back after about five minutes. I got my eyes flushed, ran back out there and that’s when they had the water cannons out and I got drenched by that for a while. I decided I would fall back for a little bit and catch my breath and went to the left side of the bridge where they were trying to flank us, so we were just spreading out the cops by walking further in the field to the left. Tear gas canisters starting flying out. And I got a lung full of that too. It’s important not to panic if your ever breathe in the tear gas, because as soon as you start gasping for more air, it fills up your lungs, and your lungs start restricting. I saw one kid just fall over and his eyes were bulging out, he was coughing up, and almost foaming at the mouth because he couldn’t breathe. So, we circled around him and started praying that he could feel better, that his lungs would clear. He got up eventually about after a minute or two of prayer. So, seeing the power of prayer out there as well. Mind blowing.

photo by Rob Wilson

NL: And you were soaking wet at that stage too?

VO: Yeah. My clothes were soaked, and I was still covered in pepper spray. And I just had to go back on to the bridge after that because the tear gas had caught wind and flew back onto DAPL’s side and they fell back first. So, everyone said let’s go back to the bridge. And that’s when flash grenades starting going off, and those things are loud. Concussion grenades.

NL: Were those going off right by you?

VO: Yeah. One blew up right in front of me. It’s a real bright flash, pieces of shrapnel and rubber, smoke. It kind of shook me a little bit, but after years of punk rock I had already lost most decibels of hearing so it wasn’t too bad. But, it definitely shook me a little bit.

NL: Were you seeing other people injured around you on the bridge?

VO: Yeah. There was a point when I was standing with a plywood shield that someone had given me when they fell back and I was holding it, hoping not to get shot in the groin because I saw people getting shot right in the groin area and being incapacitated. It was just bad. And this one woman got shot and fell over and I wanted to help. Luckily the medics were there and they just picked her up and dragged her off. But, I was standing there with this plywood shield that someone had given me and this guy was putting on a rain poncho and he had just put one arm in and got shot. He was maybe two feet away from me. And just hearing rubber bullets whiz by me, it was like wow, this is real: these guys are really trying to inflict harm on us.

photo by Digital Smoke Signals

NL: And once you went back to the camp did you have to go to the medical tent?

VO: Yeah. Eventually, I fell back due to hyperthermia. I didn’t realize how cold I was because I had been standing for two hours straight with that plywood shield. Once I decided to fall back, that’s when it hit me after I had left the front line. I had to thaw out for a good thirty minutes. I couldn’t feel anything. I said okay I need to go to the medic tent, and as soon as I did that, that is when the hyperthermia started kicking in. It took me a while to get back on my feet.

NL: What kind of services did they provide for you in the medical tent?

VO: When I got their they took off all my clothes to get me out of the wet clothes that I had been standing in. They wiped down my face and my hands to get the mace out. And then they gave me shoes and clothes to put on, blankets and hot tea. Anything to get my body heat regulated.

NL: What was the rest of your night like? Were you sleeping in a tent that night? Did you have a warm place to sleep that night?

VO: Actually, that night, I didn’t do much sleeping. After I went to the medic tent I took a couple of hours back at the kitchen to eat something and get myself together and then I got up and said alright, I’m going back out there. So, I went back out for a second time to the bridge. In my mind, I can’t rest knowing that these people are inflicting harm on women, children, elders, people who were just praying. So, I got up and went out there with my adopted brother and we went out there. By then a lot of the chaos had slowed down. The firetruck was still hosing people down. It was a light police presence at that point, but it was over fifty cops still.

NL: Did you have any idea that this was an event that would become front page news around the world? That a major incident was unfolding?

VO: Not at all. My first reaction was I just want to be out there to protect the elderly and the woman and children. That was the way that I was brought up. That’s the way that the tribes believe too. That is the future. I just knew that I should be out there to offer support and protection.

NL: How do you summarize the power of prayer at that moment? The camp itself was a prayer camp. Explain to us the power of prayer in that struggle.

VO: Well, that one is a tough one because it is subjective to each person. But being in prayer, praying to whoever you believe in, is amplified because you’re giving up so much of yourself, selflessly, to this prayer, to the protection for those around you. At least from my own experience I was praying for the safety of everybody, that no one would get hurt, and more importantly, no one got killed. Because once those shots started firing off and the explosions, I was just praying that no one got hurt. What was challenging was praying for the DAPL side. I was praying for forgiveness for these people. And that was kind of tough because they were willingly inflicting harm on people. I was also focusing on different deities that I’ve come to believe in and to pray to them that they offer protection and do the things that I can’t do.

NL: And then later that night did you eventually get some sleep?

VO: No, I really didn’t sleep that night. I stayed on the bridge until the sun came up. I had in my mind that I didn’t want to see us leave. There was something really symbolic about the bridge. Who is going to leave first? Us or you? Who’s will is going to break first? And I really couldn’t sleep so I stayed on the bridge and did what I could until the sun came up, and if I could hold the bridge with my other brothers and sisters until the sun comes up, then that’s a victory, so I just stayed up.

NL: Could you describe what the mood was like in the camp on the day following the police violence at the bridge?

VO: I tried to go back to work in the art tent and friends told me to take a day to rest to get myself together. The shock, I guess, hadn’t really sunk in yet. There were mixed feelings around camp. Everyone’s tensions were high. Stress levels were high. The biggest thing was that there was compassion for one another and it created more community within the camp itself.

NL: And this might be too personal, but did you have any lasting psychological impacts from your experience on the bridge?

VO: Yeah. It really didn’t hit me until a week or two later because I went straight back to the art tent working, printing as many patches as I could, so my mind was pretty occupied. But there came a time when I broke down. I was like wow, this actually happened, people really got hurt, and now I feel like I am barely getting over the PTSD part of it all. It has been hard to sleep some nights. I fall asleep around five or six o’clock in the morning now and it is hard to be back in quote normal society. Just seeing people going about their lives.

NL: How fast did it take for news of the injuries to circulate around camp – the news of the Native elder who had a cardiac arrest, the medic who had her arm blown apart, and the Native woman who had her retina detached?

VO: It took us about a week to hear about all the injuries just because we were cut off from the outside world. Technology really wasn’t working for us. I’m not sure what kind of tactics they were using to block out our cell phone signals, so we really couldn’t be in contact with the outside world to hear what was going on. It took us about a week – word of mouth – to learn about the injuries. Also, friends and family who had got back from hospitals were returning with [rubber] bullet wounds almost the size of a fist. And a friend of mine who had gotten shot in the kidney was coughing up blood for almost a week.

NL: You are very much describing a war zone. Moving on to other events, were you at the camp during the Thanksgiving bridge crossing across the river?

VO: Yeah.

NL: Was that something you partook in or were you working in the art tent that time?

VO: I was in the art tent that morning. That was one of our biggest actions because we had the largest amount of people working there at the time. So, we took every banner and every patch that we had printed out there and we crossed the bridge which was pretty amazing.

NL: Did people think that the police would unleash their weapons again?

VO: After the night on the 20th we just knew that these people were intending to do harm. To expect the unexpected and to prepare for the worst and know that they are here to hurt us. So, we crossed and there was a makeshift frontline of plywood shields just to protect people as they were crossing over the bridge because we didn’t want to get shot by rubber bullets. And more importantly we didn’t want people who were coming over to pray to get shot by rubber bullets again.

NL: And this was the same weekend that all the veterans were arriving at the camp. Correct?

VO: Yes.

NL: And what was the vibe in the camp like knowing that 3,000-plus vets were coming to the camp?

VO: A lot of mixed feelings. People had a lot of high hopes that there was this protective force to help us. And there was a lot of concern that we want non-violence here. That this is supposed to be place for non-violent prayerful action. We were excited because we had our protectors here, but we knew we didn’t want agitators here. So, there was a lot of conflicting emotions, but, generally I think everyone was excited in a positive way because now we have our warriors here to protect us, in case anything happens.

NL: Were there concerns that with so many non-Native people arriving to camp it might disrupt a Native-led camp where the Native presence had been so much larger than the non-Native, ally presence?

VO: The thing is, as far as the vets were concerned, is that they knew where their place was. They knew they had to respect the land and the elders and their wishes. They were allies. There is a chain of command that works at the camp too. A level of respect. Everyone was okay on that.

NL: This was the same weekend when the Army Corp of Engineers announced under pressure from the Obama administration that they would not grant a permit for DAPL to drill under the Missouri River? Where were you when the news first broke?

VO: I was in my first and second home – the art tent – so I was right there working. Getting things ready just in case we had to evacuate, so we were putting together bins of prints, posters, and supplies. I was right in the middle of a work day and someone said, “It’s over. They didn’t grant the easement.” I asked: “What do you mean it’s over?” It kind of felt fake. (Laughs)

NL: So, when you first heard the news you thought it wasn’t true?

VO: Yeah. It just didn’t feel real.

NL: When did it start to sink in?

VO: I had to see things for myself. It’s one thing to believe social media, it’s one thing to believe the news, one thing to believe a person. But when your eyes and your spirits there, then it’s real. I took a minute to walk around the camp and sure enough I just saw everyone cheering. The crowds started gathering around the sacred fire and everyone was celebrating. So, that’s when I knew it was actually happening.

NL: And what was it like that night at the camp? Was it a celebration all night long?

VO: Yeah. It was a huge celebration at the main fire and at the dome. There was a circle dance going around inside the dome and everybody there was celebrating. Same thing at the sacred fire. People were cheering.

photo by Joe Brusky

NL: What type of conversations were being had about being too overly optimistic over the victory versus the need to be vigilant with the Trump administration coming in soon? Were those conversations happening immediately?

VO: Yeah. Almost immediately. Just because it didn’t feel real. Even still I am still skeptical that they are not drilling. People were saying that they will still drill anyway and pay a fine. People were saying that we need to keep an eye on the DAPL side, did they really stop working, and who’s monitoring them? Who will hold DAPL liable and responsible for what they are doing? We wanted to see the barricades gone. We wanted to see drill pad dismantled. That is the victory I wanted to see and the one I heard people talking about the most.

NL: When the news broke, the weather turned as well, severe snow storms were hitting the camp.

VO: Yeah. The blizzards that everyone was preparing for started to hit.

NL: How did that impact life at the camp?

VO: Life at camp became rough for people living in pop tents. The blizzard just tore through tents like nothing and broke them apart. We were just buried in snow.

NL: Was their concern that the weather was going to put people in serious harm?

VO: Yeah, especially people that were not familiar with that type of weather. I’m from Texas. I never get hit with a snow blizzard that hard, where it drops to -20. I have never seen that before. It can be deadly to those who are not prepared for that type of environment. That was a big concern with the leaders in the camp. Not wanting to see anyone get hurt.

NL: Do you know what the status of the art tent is now that the camp is down to about a thousand people? Is the art tent still running as we speak?

VO: The art tent is in storage for now. The cold weather and the wind chill made printing too difficult.

NL: To conclude, I am curious about your thoughts on the role that an art tent can play in mass actions. Do you think that we are going to see more art tents at pipeline blockades wherever they might occur? Basically the tactics, including the art tactics at Standing Rock, duplicated at other actions down the road?

VO: I feel that art had a big part to play in this whole movement because it brought everyone together regardless of race, color, creed, or social status. The fact that you were able to hold something tangible in your hands that said, I am here for the movement, for the people, for the purpose, it really brought us all together and put us under the umbrella of one tribe, one nation. So, I think that art tents are going to be a very integral part of all the movements from now on. Especially seeing it firsthand how people reacted to the art, and how it reflected the ideas of the movement.

To learn more about the NO DAPL movement see:

http://standingrock.org/

http://www.ocetisakowincamp.org/

http://sacredstonecamp.org/

http://ip3action.org/

http://www.ienearth.org/

https://www.facebook.com/DigitalSmokeSignals/

Great conversation! inspiring and motivational. Thanks for sharing!

Bruce, https://www.printavo.com