I’m in Lubumbashi, DR Congo for three weeks, doing research and presenting about my work on the history of the use of Congolese uranium in the Manhattan Project. I’m staying at an art center called Picha, in an old house along Avenue du Parc, with a view out across the brownfields to the massive Gecamines smelter and its ancient chimney, the tallest thing in any direction for hundreds of miles.

Today I went on what amounts to a small pilgrimage, along with Jean Katambayi, one of Picha’s member artists, and Isaac, who runs a small tour firm. We drove for about 50 kilometers out from the bustling center of Lubumbashi, through a bright blue-lit countryside choked with the 12-foot woody stems of invasive Mexican sunflowers, past pit after pit after pit of chalky grey soil thrown up in tailings heaps around mine operations extant and extinct. We turned slightly right, and pulled up before a painted concrete gate that spanned the roadway. Across the top was painted the words “Site Touristique Lumumba” or “Lumumba Tourism Site”; a name which doesn’t sound as awkward or inappropriate in French.

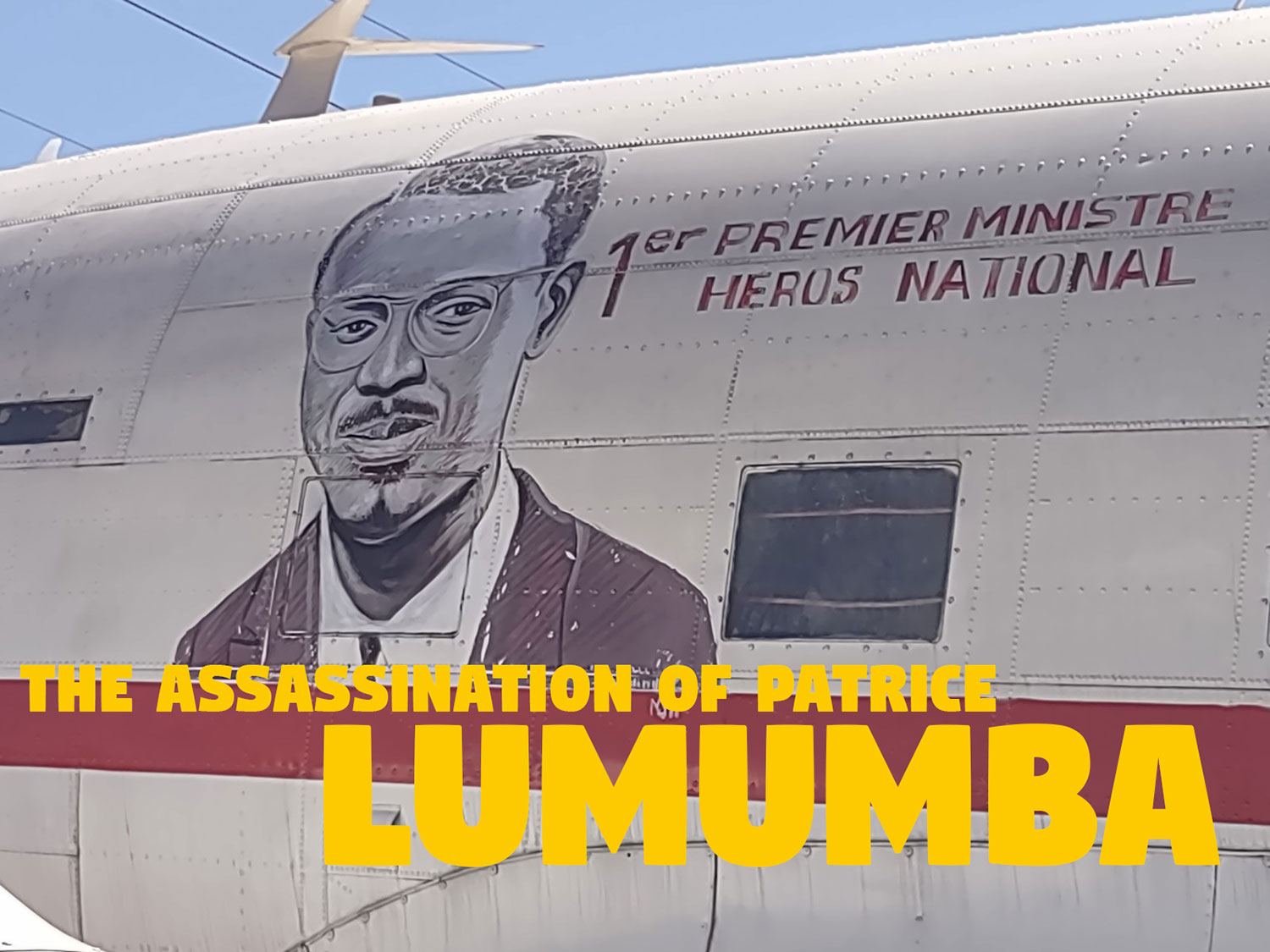

The sunflowers immediately disappeared- this road doesn’t get enough traffic for the seeds from their massive conglomerations to be spread by the constant churning of tires. The trees were clean too, uncoated with the red dust that duns everything at roadside from here to the city. We pulled into a shaded area within view of a modest structure covered with mirrored glass, and a tall, ectomorphic statue painted gold. There is also a plane here, painted with Lumumba’s face- intended to represent the plane that brought him here from the capital

A man in a bucket hat wearing body armor puttered up on a motorcycle and Isaac explained our presence. He nodded and we walked over to the statue. It was raised up on a plinth with tiled concrete stairs; the precise haircut, neat suit and angular limbs instantly recognizable even mildly distorted in a folk rendering that had a bit of a Modigliani quality to it. It was very quiet; a small wind was tossing around some durable leaves. Isaac motioned me over to where he was standing between the statue and a six-inch tall star-shaped concrete enclosure surrounding the apparently dead trunk of what looked to be the largest tree around. “Shall I explain?” he asked.

Patrice Lumumba was the first Prime Minister of an independent Congo. After the Belgian King handed over formal control of the country in a ceremony in June of 1960, Lumumba gave a speech excoriating the colonial legacy that had bitterly and ruthlessly exploited the people and landscape of Congo for so long. The assembled dignitaries of Europe realized that they had something on their hands that they hadn’t reckoned properly with: an African leader who intended to exert control over the land and its contents in ways that might be assumed to deny that control, which they had previously enjoyed, to them. They had not realized that the prospect of decolonization meant that the decolonized would be at liberty to decide who got to mine and cut and drain the territory for the ingredients of industrial expansion- and war.

The speech was Lumumba’s triumph, and also his doom. Like the flip of a coin that reveals the choice you had already made, the industrial enterprises and intelligence agencies that had long dominated the economic life of Congo went straight to work on a project of preventing Lumumba from putting his simple project of Congolese control over Congolese territory into action.

One of the first dominoes to fall was the secession of Katanga, the southernmost province of Congo and perhaps its richest; the site of hundreds of mines that had produced an enormous quantity of copper, cobalt, and other metals, as well as almost all of the uranium that had been used to develop and deploy the first atomic weapons. Relinquishing control over that region was inconceivable to the Belgians- and also to the Americans, whose global power and hegemony had been cemented with the atomic fire they had summoned into being through the scrying of Congolese stones.

American President Dwight D. Eisenhower had been under pressure for months from his demonic svengali, CIA director Allan Dulles, to do something about Lumumba. When he finally relented, he issued an order to that Lumumba should be terminated as quickly as possible, which simultaneously stunned Dulles and his ilk and then immediately galvanized them to frantic action. Within weeks the chief of the CIA’s Congo station Larry Devlin was welcoming a man known as “Joe from Paris”, who turned out to be psychotic CIA poison scientist Sydney Gottlieb, best known for his pharmacological mind control experiments. Gottlieb provided to Devlin a vial of poisoned toothpaste with specific instructions that the killing not be traceable to the United States.

The poisoned toothpaste was never used, however, because the Belgians got to Lumumba first, and without any pretensions at subtlety. After a failed attempt to escape house arrest in the capital Leopoldville, Lumumba was captured on the road to Élisabethville and rendered to a prison camp, where he was beaten mercilessly and made to eat a copy of his famous speech.

Within days, Lumumba was on a plane to Katanga, into the hands of his direst political enemy, the Katangese head of state Moise Tshombe. The Belgians had arranged for his transfer to the portion of Congo still under their most explicit control- the region of spectacular mineral profligacy that was the source of most of the country’s foreign exchange; as well as the site of the mine that yielded up the stones that made atomic warfare a reality.

When Lumumba’s plane landed, he and two comrades were taken to a farmhouse near the airport and beaten again. Tshombe and assorted Katangese dignitaries arrived to offer insult and a few choice blows, and when everyone was satisfied Lumumba and the two others were loaded into a vehicle and driven some 50 km north of Lubumbashi, to just past the junction of the road to Mwadingusha.

Lumumba’s two colleagues, Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo, were shot first, and their bodies rolled into a shallow pit that the Belgian officer in charge of the operation had ordered dug. This man, Frans Verscheure, then ordered the other Belgian present, a police captain named Julien Gat, to puosh Lumumba up against a mupanga tree. A fusillade rang out. They took Lumumba’s body by the hands and feet and tossed it into the pit, on top of Okito and Mpolo. They hastily shoveled sand in over the bodies and then loaded up and drove away.

While the Belgians were massacring Lumumba in the circle of vapor lights from their vehicles, a young boy who had been checking his line of snares was hiding in the scrub at some distance, watching them. After the vehicles departed, he ran to his nearby village to tell what he had seen; the chief immediately mounted a bicycle and rode off towards Élisabethville (now Lubumbashi) in the dark. When he arrived at a police station to tell what he had seen, he was immediately arrested.

I never heard that someone saw them do the job, I said. Isaac nodded, and gestured to a patch of earth next to the statue. They buried them over there, he said.

When the Belgians heard that they had been observed, they panicked. The official word was going out on radio that Lumumba had escaped and had been killed by outraged villagers; but it was certain that the story that the chief had brought into the city would spread, so Belgian police commissioner Gerard Soete returned to the site with his brother and Verscheure to finish the job.

Soete commandeered a vehicle from the Union Miniere headquarters and filled it with metal drums and bottles of sulfuric acid, and then returned at high speed to the grave-site. The bodies were disinterred and the three men dismembered them with a hacksaw, dissolving the bodies in the barrels of acid. Soete cut off a couple of Lumumba’s fingers as mementos, and used pliers to pull out one of his gold teeth. Verscheure fished a bullet out of what remained of his skull. What was left was discarded in the sand by the side of the road.

For decades the site of Lumumba’s assasination remained known, but unremarked. After Laurent-Desire Kabila evicted Lumumba’s successor and enemy President Mobutu Sese Seko from power, he ordered the site to be rehabilitated, a mausoleum built, and statues erected. At the site today you can see exactly how far those orders advanced before he himself was assassinated.

The mausoleum contains the soil from the shallow grave. The tree against which Lumumba was shot is ringed by a concrete star, and although mostly dead, retains a strip of bark that feeds a globe-shaped mass of foliage. The site guard and some friends were lounging in its shade as Isaac finished his recounting.

On our return to Lubumbashi, we drove through neighborhoods along the edge of the airport looking for the site of the Brouwez house, where Lumumba had been taken immediately after his arrival. For decades it functioned as the site of pilgrimage that the more remote assassination site couldn’t, but at some point within the last five years or so the site was sold, as the neighborhood filled up and transformed during Congo’s demographic explosion. It was there, said Isaac, gesturing to a concrete wall. Just residences now.

There was nothing to see. People behind us were honking. Isaac waved a hand at them and we pulled away.