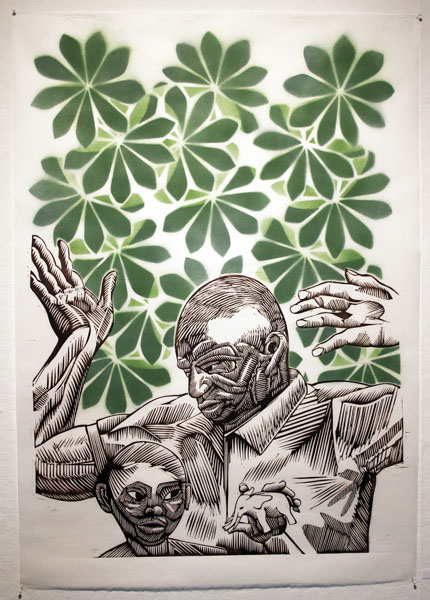

I just opened a solo show of prints, installation, sound, and video in the Pacific Northwest College of Art’s Gallery 214. It’s up until the end of November, so if you find yourself in Portland, go check it out. It’s all about traps- in culture, in biology, in psychology. How do we get the world to give us what we want- and how do we get stuck wanting what we’ve taught ourselves to get. The show features collaborations with Portland filmmaker Jodi Darby and MC Mic Crenshaw; Jodi and I made a movie wherein I reenacted my father faking his death in order to abscond from the British Air Force and fly helicopters for the CIA in DR Congo, and Mic layered some of his rhymes and thoughts over field recordings I made in a vanished Congolese village.

Click through for more images, and an artist statement!

In 1965, my father faked his death in a scuba diving accident in order to abscond from the British Air Force and pursue an adventure, flying helicopters for the CIA’s cataclysmic interventions in the Democratic Republic of Congo. He left behind two daughters, a wife and a family broken by the thought of his loss- and on the day he did it, he hitched a ride to catch a train cross-country and then take a ferry to Belgium, Congo’s former colonial power. On the ferry he met my mother.

My father’s Congo experience involved aerial excursions over the East Congo territory occupied by Che Guevara’s rebel cadres, numerous narrow escapes from disaster and slaughter in remote locations, and a brief stint as US-installed dictator Mobutu Sese Seko’s private pilot. He told his colleagues in Congo that his family had been killed in a car crash.

The US and Belgium had organized the assassination of Congo’s first independent Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba- whose death has been called the most significant assassination of an African in the 20th century- and the world they wanted the newly-installed Mobutu to oversee was one in which they could continue to suck at the open wounds they’d gouged in Congolese soil for as long as they saw fit. The people of Congo were never much more of a consideration than the wildlife- and usually less. The wildlife, at least, was not passionately opposed to the betrayal of their hard-won independence.

My father’s work in Congo contributed to the horrible and chaotic plunge experienced by the citizens of that country in the latter half of the twentieth century, as the country was wrung out by Mobutu and his masters and thrown into the rag-bin of history.

When Mobutu stopped paying his soldiers, because he wanted to keep for himself the money that Belgium and the US were giving him for that purpose, the army received orders to fend for itself- and that led to a countrywide campaign of looting, raping and usurping. One consequence of that unleashed force was the near-complete extirpation of large mammal species throughout the vastness of that country, as soldiers used their government-issued weapons to hunt and sell buffalo, antelope and elephants for meat and ivory. The savannahs are still empty- when I interviewed a village chief in eastern Congo about historic wildlife populations, he told me that his name, Njate, meant buffalo, and noted that no-one would name a son that now, since the buffalo have been absent for decades. “We couldn’t leave our villages at night back then, ” he said, “because the elephants would kill us.”

My father always wanted to be a hero. He could fly helicopters in situations that others couldn’t. He wanted to be special, to be needed, to not be training raw recruits in desolate England, trapped in a dying marriage under dark clouds. He wanted to be out there in the sky, choppering over the endless broccoli of the tropical forest, saving nuns from butchery at the hands of “savages”, being important, being special, being heralded. He looked around at his life and his job and his family and he saw a trap. So he chewed his arm off, and he made his escape. And he plunged himself into a historical current that saw the heart of the African continent torn apart, dug open, and drained like a headless chicken to feed the Western world’s industrial and technological growth. Sacrifices had to be made, and continue to be made, to ensure the continued dominance of white terror on this earth. That was nothing new, of course. But for me it’s personal.

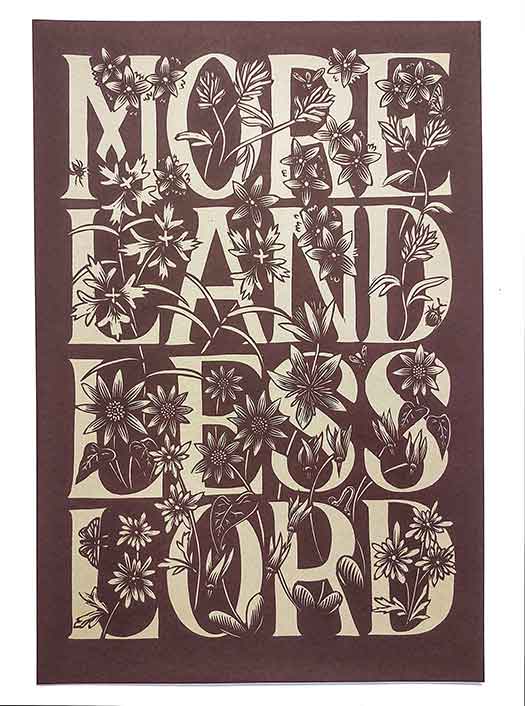

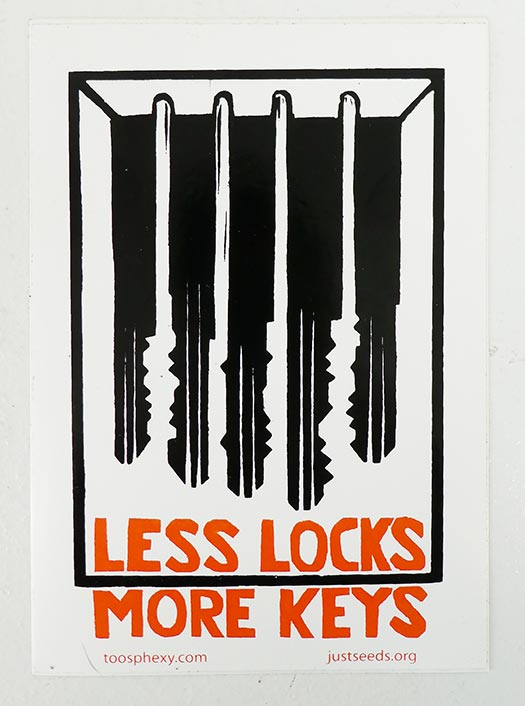

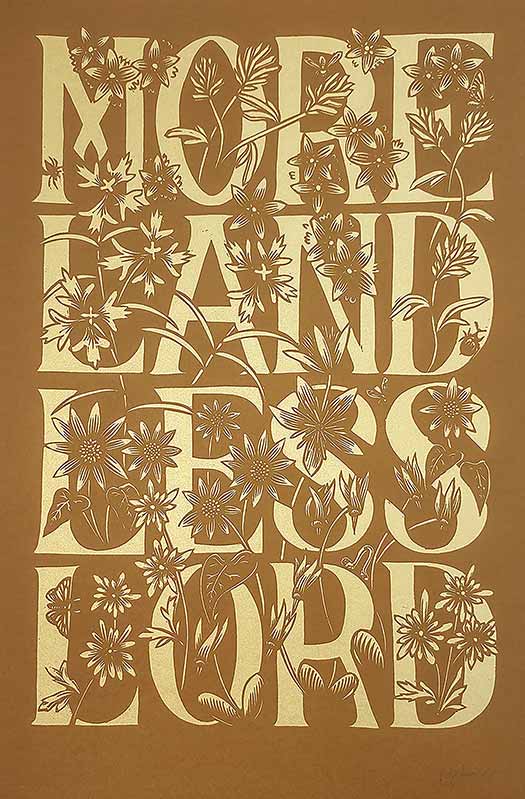

This show is about traps, how they occur in culture and history and biology. Humans are the only vertebrate species that makes traps, and that simple fact provides a lens through which to view all our efforts that I think is about as clear as it gets. We are the only species, outside of a broad slew of worms, insects, and spiders, that creates areas of potentialized lethality in the evironment, stores of wound-up death-dealing that wait on the trail or in the forest or deep in our psychological fundament for something to set them off. But traps are more than just clever assemblages of sticks that hoist an unsuspecting antelope into the air- they lurk in the heart of our culture, in all cultures, in the core of how we make our way in the world. Many of the turns our cultures take are “progress traps”, dooming us to follow channels of material advancement towards deep, dark and inescapable canyonlands. Agriculture is a progress trap. So is Capitalism.You could say that the way in which a trap builder conceives the imagining of future consequences and future advantage, is the essence of what it is to be human. Traps are emblems of how we struggle against each other, against the world, and against ourselves.

You can read more about the work I’ve done in Congo at lomamibandanas.tumblr.com. Follow me on Instagram and everything else as @TooSphexy, on my website TooSphexy.com. Send me email at mold2000@yahoo.com. If you want to read a book about my father and his crazy life, there’s one called “Renegade Hero” by Michael Hingston. Seriously.

Thanks are due to many, chief among them being my collaborators Jodi Darby (with whom I made the movie) and Mic Crenshaw (who provided sound pieces). Among that multitude, count Elizabeth Robertson, Gary Robertson, Brendan Flanagan, David Harrison, Koto Kishida, Mack McFarland, Terry Peet, Joan Peet, Beckey Kaye, Lori Ann Burd, Amy Harwood, John and Terese Hart, Maurice Emetshu, LeRoi Kishishi, Salva Bapena, Omba Florence, and the chiefs of Lomango, Wemambuli, Katopa, Lole, Oluo, Makoka, Kakungu and Tchombe Kilima, Maniema Province, DR Congo.