The campaign to stop the proposed Crandon Mine from poisoning the Wolf River in central Wisconsin is one of the great recent environmental victories in North America. It is also one of the least known struggles for its name recognition and its history remains obscure, even in much of Wisconsin. For 28 years (1976-2003) activists in Wisconsin organized to prevent a zinc and copper mine near the Wolf River. The movement, itself, was extremely diverse and described itself as Native and non-Native, rural and urban, environmentalist and trade unionist, and hunter and sport fisherman. The coalition organized against tremendous odds. Both corporate power and the then-Governor Tommy Thompson supported the mine and a procession of multinational mining giants, EXXON, Rio Algom, and Billeton all marched into Wisconsin, yet were defeated by the grass roots movement. As a result, Wisconsin has become known as unfriendly to mining interests and in 2003, the threatened land was purchased by Wisconsin Tribes—the Sokaogon Mole Lake Chippewa and the Forest County Potowatomi.

The following interview by Nicolas Lampert is with Susan Simensky Bietila, a Milwaukee-based artist who was invited to join the movement in the mid-1990s as a street medic. She instead became involved as an artist and created giant puppets, creative signs for marches, and a series of over 30 tombstones that were placed at the State Capital in Madison and other locations, memorials to rivers that had been poisoned by mining. Her last tombstone read “R.I.P. Crandon Mine”- celebrating the proposed mine’s defeat and the tremendous victory that was won by a people’s movement. The interview took place in July of 2009. (a shorter version of the interview was recently published in AREA Chicago in issue #9 “Peripheral Vision.” )

When did you first get involved in the Wolf River campaign and in what capacity?

In 1997, I was approached by Milwaukee members of the Wolf Watershed Education Project because of my experience with direct action and as a street medic They anticipated things heating up and invited me to help them transition into a new phase of activism. They were very committed to anti-mining environmentalism and supporting indigenous rights, but had little experience at militant demonstrations. Their role was educational-doing presentations for community groups and at schools as well as lobbying. It was conceivable that armed self-defense could come into play if there was an attempt to mine. They were well aware of the history of Native American militant actions in Wisconsin-blocking train tracks, building takeovers and sit-ins lasting months. I thought, however, that there would be a resolution without things coming to a desperate standoff. This is what transpired. It didn’t hurt that Exxon’s name was infamous due to the Valdez oil spill in Alaska. This certainly made people skeptical of their promises not to pollute the water table. My first project, in 1999, was a combined ‘road trip’ radio interview and compact tutorial, to get up to speed on the movement. On the way to a Department of Natural Resources (DNR) hearing in Door County I taped an interview for the Milwaukee pirate station Radio Bob-The Wireless Virus. Three longtime activists recounted the effects of sulfide mining and the history of the truly unique movement. Environmentalists, indigenous activists, hunters, fishermen, labor activists, academics, students, tourist industry business people, and small town government people were all working together. To me, it was a model of critical thinking and creative direct democracy and I was hooked.

Tell us about your involvement as an artist and were street puppets a medium that you regularly employed at the time?

Yes. In 1996, I went to the Active Resistance gathering in Chicago, where my son had gone to help build giant puppets with San Francisco artist David Solnit for an Art & Revolution parade during the Democratic presidential convention. Shortly thereafter, David and Alli Shagi Starr did a wonderful presentation in Milwaukee at the Riverwest Art Center where David presented a slide show that documented decades of using puppets during protests and Alli led a contact dance improvisation workshop. It spurred the reunion of people who had done street theatre in Milwaukee in the late 1980s, against the US involvement in El Salvador and Nicaragua. In 1998, John Augustine (who had been part of the Central America street theatre group) and I built a wood and backpack frame for a giant flat puppet in David’s style, of then Wisconsin Governor, Tommy Thompson whose main advisor was a former EXXON lobbyist. We sewed a suit and made him a fools cap emblazoned with the words, “FOR THE WOLF RIVER” with the ‘Skull and Crossbones’ for poison on one peak and “FOR MINING COMPANIES $” on the other. The puppet was loaned to anyone who wanted to use it and it traveled for years.

What other visual tactics did you use on the Wolf River Campaign?

David’s gave me a color photo of Pacific Northwest indigenous people demonstrating for the restoration of the free running rivers to bring back the Salmon. They were carrying large cutouts of salmon drawn in traditional Northwest Coast style, held aloft on sticks, like picket signs. This gave me the idea of making screen prints of trout with one side as a live trout and the flip side as trout skeleton, the ultimate result of sulfide mining in the Wolf River watershed. We then distributed them throughout the crowd at a rally at the Wisconsin Capital. People immediately wanted them. They were attractive items and told the whole story, no words needed. They were carried by all types of people from a Boy Scout troop whose camp was endangered by the proposed mine to resort owners in their 80s.

Tell us about another project that you were involved with – the gravestones that you created? Where did that idea derive from?

The idea evolved collaboratively during the Milwaukee area meetings of the anti-mining group. The idea was to create a cemetery of dead rivers – grave markers each with the name of a river poisoned by mining. I was amazed at how many rivers had been polluted worldwide. I stopped after more than 30, and could have continued. Local activists and Wobblies assisted with the prep work. We scavenged bicycle boxes and the wires from yard signs used during elections and attached them to each piece. I designed and painted most of the them. Claire Vanderslice did a few. Like the giant puppet, they were made to travel and could be packed into a car trunk and set up wherever people were fighting the mine. In April 2000, I brought the tombstones to a big march and rally in Madison and started to set them up on the Capitol lawn. There were marches coming in from the Campus on the west and from the power company on the east, farmers marching against a long distance power line threatening their farms with eminent domain. The police confronted me right away and told me that I could not set them up on the lawn. So I duct taped them up along the walkway leading up to the Capitol building where the rally was to take place. People walked along and read them intensely and not just the people who had come to the demonstration. In the years that followed, they traveled as an installation to the Riverwest Art Center in Milwaukee and also to rural roadsides and then in the end, to the victory celebration on the Mole Lake Reservation.

What was it like to take part in such a diverse movement?

I was drawn to this movement because it had so many inspired elements. These people were going about things in the way that pre-empted the usual marginalization of radical activism by the powers-that-be and the corporate media. The activists were absolutely impossible to stereotype — people from small towns all over Wisconsin as well as from cities, all professions and ages. I never imagined being in an organization with people from hunters and fisherman’s groups (NRA members), and retired Chicago police officers. It was so much easier to imagine working with Indigenous groups as well as environmentalists, socialists and anarchists. The idea of standing up to some of the most powerful corporations in the world with a group that was so diverse seemed to have great promise and differed from the anti-capitalist actions that I was accustomed to. It was not a surprise that the campaign succeeded.

How did people in the movement accept you as an artist? Was there an appreciation for what artists could add in the movement?

I agree with David Solnit who describes our function as artists as “animators” rather than organizers — giving people the form to express their ideas and feelings.

Although no one discussed the role of artwork in the movement per se, every piece of artwork I did was used over and over again. My artwork was posted on the group’s website and I had enthusiastic help with research and production in each project. Other people wrote and performed poetry and others did music and guerilla theatre. I did not expect that this would be a movement like the anti-globalization demonstrations where puppets and performance art would play a major role. People of every generation and cultural experience were involved. It was a movement open to all contributions, and some people valued the role of art and others probably did not. But there was no hierarchy. I did not have to seek anyone’s approval to do what I wanted to do. The movement included such a diverse swath of cultures niches from a Chicago illustrator of fossils for paleontologists, to duck decoy carvers, to UW professors, high school and college students, to tribal elders.

What were some of the interactions that you had when you presented your art to people in the movement?

Everything I did was used. No fanfare involved. I also did a drawing for a poster for the anti-mine Citizens Assembly in 2001. At the conference dinner, I sat with a UW student who was an Andean indigenous musician, and we spoke as we could, with my little Spanish and his little English. He thought that my contribution was important. He was totally aware of art as integral to political movements.

Did projects arise after the victory?

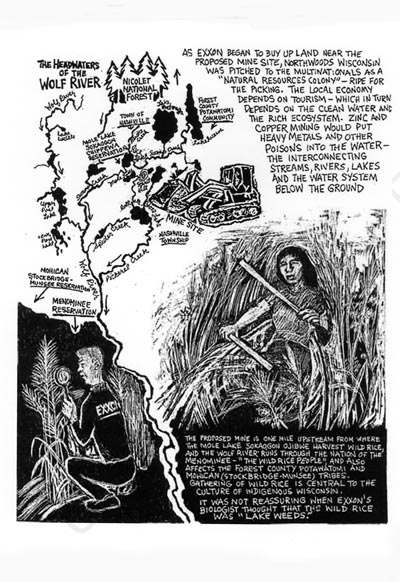

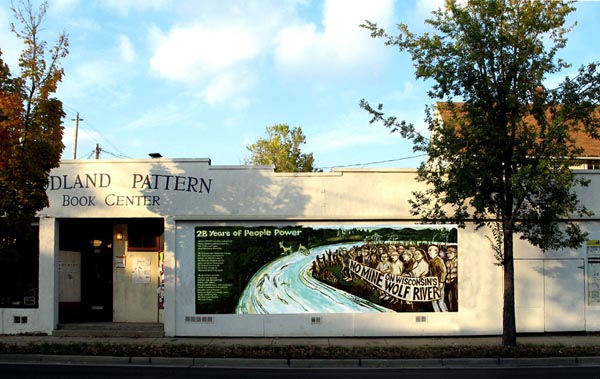

Yes. I had already been drawing a graphic history piece for World War 3 illustrated magazine about the Wolf River Campaign when I heard about the victory and added the information to the last page. Also, in 2008, I was invited to do a mural as part of the Milwaukee art show Seeing Green. The mural was 8 x 24 feet and hung outside the Woodland Pattern Book Center on a heavily trafficked street in Milwaukee. When you published the story in World War 3-illustrated, did you find that the people were generally aware of the history of the Wolf River Campaign? Or was your work largely introducing this history to the reader? I think the story of Wisconsin’s anti-mining movement is largely unknown. The other people who did stories for World War 3-illustrated didn’t know about it. As it stands, very few people know about the Treaty Wars in the 1980s either. People in the international Indigenous Environmental Network know about it and it is infamous to the international mining industry, which clearly recognizes Wisconsin’s example as threatening to them.

What did you take away from this experience? Meaning how was it to work as an artist during a movement and then help preserve the memory of the movement?

Art can teach people about history. When I painted the mural in Milwaukee, students at Bay View High School helped and had not heard about the anti-mining movement or the history of the treaty rights movement. So, the mural-in-progress was a valuable teaching tool. All the art classes saw the work in progress over the several months it took to paint. Students came to see me afterward and told me afterwards about taking their families to drive past the mural. They had a connection to it and were proud of the work. The mural was seen by thousands of people every day and when it was taken down, people complained. It had become an affirmative part of their everyday life. Overall, I didn’t have a master plan of the sequence of projects, but they have followed a trajectory. I did projects to fit the different stages of the movement during the years that I was involved and after. It was such a significant victory and so remarkable a movement and known by too few. This is still the case.

Lastly, tell us about your experience as an urban activist and artist in a rural campaign. What did you bring with you from the city to the Northwoods and what did you take back home with you from the experience?

Although I have always lived in cities, I have family members who have been iron miners in a small town in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. I have sympathy for the dilemma of jobs vs. environment for rural communities. Doing artwork for this movement, I gained a concrete understanding of the vast potential to unite people from disparate cultures against multinational corporate exploitation. It was indeed possible.

For more information on the historic victory that defeated the Crandon Mine, see the International Indian Treaty Council:

http://www.treatycouncil.org/new_page_5244111121111.htm