I wrote this article for Bitch Magazine in the leadup to the recent People’s Climate March, thinking about futility and frustration and the reasons we do the work we do.

If I were making a list of things that felt absolutely futile to protest, I’d put climate change at the top. And if I were making a list of organizations that have failed in their efforts to get the world to care about climate change, I’d put the UN near the top, too.

But this weekend, I’ll be part of the People’s Climate March, America’s largest ever climate-related protest. The gigantic rally on Sunday rally in New York City is targeting the international bigwigs in town for the UN’s Climate Summit. I’ve spent the week in a warehouse in Brooklyn, along with many, many other people, making arty props and propaganda for the event. Sometimes, this work doesn’t seem to make much sense.

I’ve been what you could vaguely call a “political artist” for much of my adult life. During my twenties, I made a lot of protest banners, protest costumes, and protest performances with protest puppets. I’ve made puppets at protests associated with anarchist conventions, at protests against political party conventions, corporate gluttony, and the prison industrial complex. I made a robot puppet costume that I called “Protestron,” which I would wear at protests and run about, chasing people and beeping at them, grappling with the giant cardboard hammer that was symbolically bashing against the buildings downtown. But over time, I gradually lost my enthusiasm for spending time at protests cocooned within the body of a series of political symbols that didn’t seem to really be communicating anything useful. I also got tired of not being able to really see where I was going. I got knocked over a lot.

The last straw for me was the A16 protests in Washington, DC in 2000. A year after the fantastically successful disruption of the World Trade Organization’s summit in Seattle, the burgeoning anti-globalization movement gathered to try to pull off the same trick against the IMF and World Bank. Personally, I’d come to DC chagrined to have missed the Seattle protests and ready to fight against the financial organizations that are responsible for making life worse for poor people around the world. But from the start, the protests seemed a little ill-fated. DC cops weren’t the buffoons that the Seattle ones had been. The city was used to dealing with masses of idealists. The obligatory giant protest puppets were being assembled in a space called the Convergence Center and the police realized they could paralyze the entire movement by declaring the place a fire hazard, locking it up with the puppets inside. Howls of anguish echoed. While the police were outside in the street preemptively rounding up hundreds of people, calls went out to free the puppets. Free the puppets? The puppets? Fuck the puppets, I thought. It seemed like the point of protesting was being missed, that a good photo op was trumping a stampede. I stopped working on protest puppets after that. I became increasingly embittered with a lot of the political communities I’d found myself within. Then 9-11 happened. I left the city and moved to rural southern Oregon.

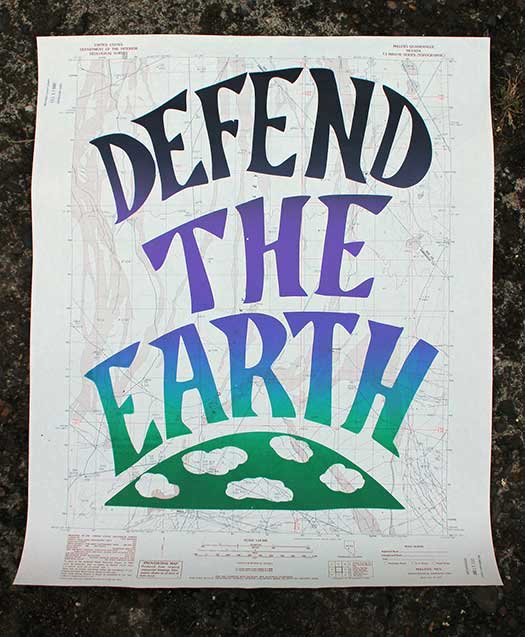

I lived in the forest for five years, in a log cabin I built from trees I felled. I gardened. I kept bees. I shared a patch of land with a small group of oddballs and a broader community of traveling activists and eccentrics. I didn’t go to protests. I started printmaking and withdrew into a realm dominated by interior thought and monologue. I read a books, learned a lot about geography and history and biology, the things that lived in the forest around me, and in the world beyond. The land-project fell apart, as such things are wont to do, when everybody reached their thirties and realized that they no longer agreed with half of the ideas that had propelled them so surely into adulthood. I found myself back in the city, a bit bewildered and casting around for something to believe in.

This weekend’s march in New York is being planned by hundreds of organizations. It’s a big sprawl of priorities and presences, diagrammed within an arrow on a poster on the wall of the art-space where I’m working. Indigenous people and youth and climate refugees at the front, followed by communities affected by Hurricane Sandy, then Labor, students, elders, community gardeners, bicyclists, renewable energy enthusiasts, then campaigners against fracking and pipelines and fossil fuel extraction, and then scientists, beekeepers, an interfaith delegation, and then, the poster says, everyone else. It’s timed to coincide with the UN’s largest ever summit on Climate Change (capitals intentional), where world leaders and high level representatives of those world leaders who can’t be bothered to show up will convene in solemn ceremony and pronounce in plummy tones that they have utterly no idea whatsoever to do about the terrifying changes barreling toward us all.

The art studio space is crowded. I brought with me about a hundred and twenty masks screenprinted onto LP covers. There’s three designs: a dark, rainy cloud, a giant wave crashing over a city, and a massive melting iceberg. I figured it would be fun to have people dress up as the symptoms of the system we live within. I’m also working with two young artist friends to design and build a giant inflatable life preserver, which will be carried near the front of the march by activists from Rockaway Wildfire, one of the numerous groups that sprung up to provide assistance and support to communities affected by Hurricane Sandy. Other friends, in a group called Culture Strike, are painting a parachute with symbols about migrant rights in the face of a changing climate. There’s a huge tree thing studded with paper mache axes off in one corner, some people from Greenpeace are gluing together huge slabs of insulating foam to make an iceberg, and screenprinted flags and pennants and signs hang from strings and ladders and drape every flat surface. It feels a lot like the Convergence Center, as if I’m going to protest like it’s 1999.

So why am I back here after so much time away? Personally I don’t think much can really be done to stop the worst of climate change. Even some kind of atmospheric chemical thunderdome that prevented all future combustion would have to contend with the vastness of the historical damage. Most of the people who’d tell you different, as the saying goes, are selling something. Capitalism is the deep, dark heart of the crisis.

As we took a break from taping together the giant inflatable life preserver, I asked fellow artists Katherine and Artur why they were here. Katherine said that she’d come to try to make some points about climate that she felt weren’t being made. “I think so much of the response to climate change takes the form of ethical consumerism, which is bullshit. Why are we told to care so much about our personal flying, when a quarter of all jet fuel in the world is used by the US military?” she said. “Ethical consumerism’s just a trick of capitalism, to make you think that the votes you cast with your dollars make a difference—and they don’t.” Artur was pensive., “I’ve mostly come to learn about how different communities are responding to climate problems. I’m getting a lot out of talking to these people from Rocakaway Wildfire. I want to try to develop alternative symbols, like these inflatables, to change the way that the standard narrative about global warming is transmitted, and to show how capitalism continues business as usual while in crisis, and how we can disrupt that.” His face split in a big German grin. “And also I just like to collaborate! It’s great to make connections.”

As the temperature of the planet steadily inches upward, making art to protest climate change feels like the most futile thing in the world. But the protest itself isn’t why many of us are here. We’ve come to connect with each other, to find people who hold similar ideas and connect to them, to make friends with each other, to maybe go out for a beer. When we come together in places like this, we can look around at each other and realize that we aren’t alone, and that we never were. To come to a protest like this with the idea that you’re going to save the world is at best ignorant, and at worst dishonest, but it’s not a bad thing to want a better world for yourself. Maybe, if you look for it in the right places, you might find a bigger self.

That was the biggest impact of the victory against the WTO in Seattle—it gave people a sense that they can win. That sense of power is important. It’s a silk handkerchief—you’ve got to grip it tight to feel it, and it’s probably going to get away from you anyway.

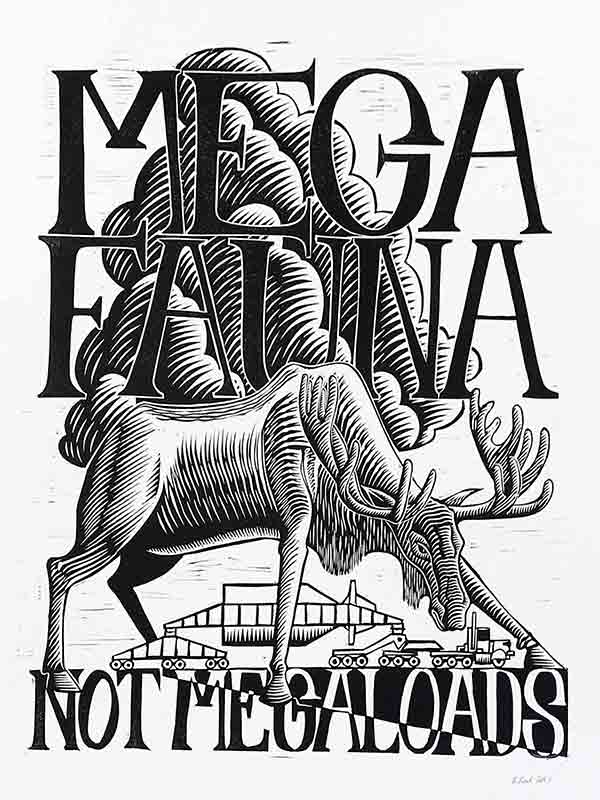

When I came back to the city from the forest, I found myself reading everything I could lay my hands on with the word “extinction” in its title. I started making prints about extinct animals, and found, in the process, a new way to think about the past and future of life on this planet: that every beautiful thing burns, eventually, and you’ll burn yourself if you try to hold on to it. We shouldn’t stop trying to create the world that we want to live in, but at the same time, we need to live right now in the world we want to create. We certainly can’t buy our way there, and we probably can’t fight our way there either. Better to make as many friends as we can, gather them close and watch the flames together, and try to figure out how to live in the light that the fire reflects.