I left Portland at about eight o’clock on a Thursday night, after a cruise through the art shows downtown. The sun had set by the time I reached Celilo Park, about ninety miles away through the Columbia Gorge. I dragged my sleeping bag to the riverbank and listened to the buzz of the highway, waiting for sleep.

In the night the screams of trains woke me, rattling deep and long and fast and syncing with the highway noise into a crescendo of motors and metal. I got up at dawn and made coffee in the hatchback and watched the river go, huge and swollen with the spring. Under the surface slept the rocks of Celilo falls, where people had fished and traded for more than ten thousand years until drowned by The Dalles dam. Celilo Village sits squeezed between the highway, the railroad, and the basalt of the bluffs- the oldest continually inhabited location in North America.

I drove to Pendleton and turned south, leaving the Gorge for the pine forests of the Southern Blue Mountains. The slopes were yellow with Mule’s Ears and other asters, nodding in a small wind with the purple camas. Small roads diverged and re-diverged until I was on gravel following the North Fork of the John Day river upstream. I drove until the road filled with holes and finally ended in a small sunlit gap in the forest, at the Big Creek trailhead to the John Day Wilderness.

Spring in the wilderness is mercurial, low clouds looming and splitting, gentle rains sweeping across the river valley and becoming torrents as they climb the far face. Larkspur and paintbrush and penstemon squeeze out of the lichenous soil, and lupins crowd the path with their star-shaped leaves holding little globes of rain. Ponderosas were glowing in the intermittent sun, and the trail was interrupted by mushrooms- little brown things, glossy ones, white ones, enormous boletus rearing like earthy clouds from the duff of horsehair trees. Windfall trees crossing the trail held embedded wires with porcelain insulators projecting, relics of some plan fallen apart. The river was loud and the puddles on the trail held flocks of butterflies puddling for minerals, big white swallowtails and little blues that made a sky-colored swarm as I passed over them, spinning around me and fluttering back to their drink. There were piles of fresh clean bones every half a mile, some young animals, some adults. A herd of freshly antler-free elk ambled across the river about fifty yards ahead of me. A little further on the clouds opened in earnest and I walked the last three miles in about as heavy a rain as I’ve experienced- a sodden trudge. I made camp at Wind Rock and crawled into my sleeping bag and ate a brick of cheese and read Mikhail Sholokov’s “And Quiet Flows the Don” until it got dark. The rain hammered my tent long into the night.

In the morning it was rainless but still cloud and cold so I finished Sholokov’s novel of Cossacks in WWI and the revolution and civil war that followed. It had been ages since I read a novel and the book was consuming me. The river was louder and closer to me than it had been when I was hurriedly pitching the tent, and after I finished the book I got up to look for dry wood. In the rain-shadow of the eponymous boulder were a string of old pack-rat nests of haphazardly piled sticks. I pulled a few handfuls off the top of each and made a fire, drying my socks and watching the sun try to come out. The trees were Ponderosa and Doug Fir and Larch, with serviceberry and ninebark flowering at riverside, frog-pelt lichens and innumerable mosses underneath.

I hiked out in the afternoon, about 9 miles to the trailhead which I reached with a daypack full of mushrooms; big white morels and nice firm Spring Kings. I found a campsite at riverside and cooked and ate the morels all by themselves with butter and salt, very slowly, before I thought about eating anything else. The Mule’s Ears were glowing in the light of dusk and the river was brown and had narrow whitecaps on it. I could hear stones booming together below the current.

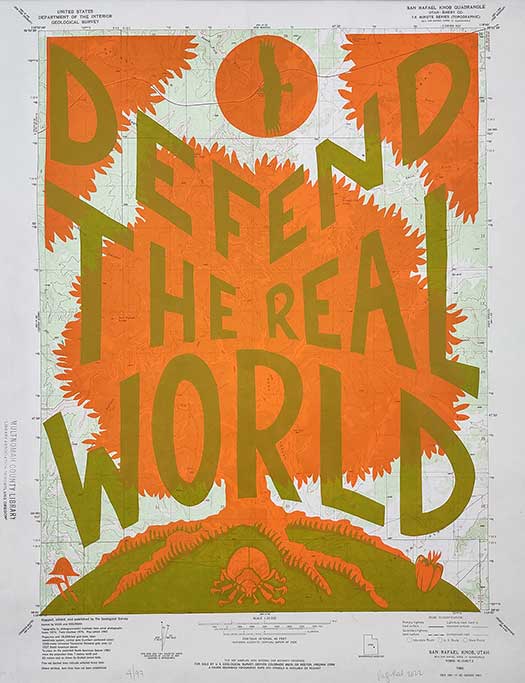

I’m ambivalent about the idea of wilderness. As a bulwark against the inevitable despoliation and exploitation of all wild spaces it’s useful, but it arises from the same ideology that wants to museum the world. It’s a liberal idea, not a radical idea, and it only makes sense as defense against the kind of extractive ideology currently riding rough across the erstwhile public lands of the West. It’s an idea that could stand decolonization. For people to value the land they have to use it, to feel themselves as a part of it. Land is not static, and museums are only as sacrosanct as the entities that guard them. When centralized power disappears within a structure like ours, the looters rush in. The real looters- the ones with machines. The contemporary right-wing definition of public lands as a territory in crisis is a tactic to suggest the need for triage- and that means cutting, digging, and trapping out everything of value from a landscape seen as sick. An anti-capitalist vision for public lands wouldn’t eliminate the use of woods or rivers or grasslands, but it would remove the profit motive and insist on use based on need rather than speculation. That vision should be indigenous-led.

The real problem is that human society is bigger than the land- it exists now only inside us, and every year that goes by the entire natural heritance of the planet grows smaller and more vulnerable like the mouse in Lennie’s pocket.

On the following morning I drove south, out of the winding defiles of the Blues up into the high smooth valleys and over into the main John Day River valley, past wisps of towns defined only by their churches and schools. In John Day city I stopped to take a tour at the Kam Wah Chung pharmacy and general store.

There were Chinatowns throughout eastern Oregon in the late 1800s, peopled by migrants who’d come in search of gold and stayed to work in mines and railroading and settle the big interior. White racism burned most of those to the ground, including the Chinatown in nearby Canyon City. The Chinese populations that remained faced continuous violence from the white settlers. The Kam Wah Chung store was the last remnant of what was once the third largest Chinatown in the West, owned from 1880 on by two men, Ing Hay and Lung On, and functioned as herbal dispensary, clinic, and boarding house until 1940.

The house is a museum now, after sitting for numerous decades boarded up with its contents more or less intact. It’s an amazing time-capsule of a vanished way of living, and of resilience in the face of relentless settler violence. The metal sheathing of the door is punctured by bullet holes, and just within are installed accordioning cast-iron plate doors for extra security. The walls are foot-thick stone and there’s another small wooden house siting on top of the older structure like a neat little cap. In the white-supremacist core territory of Oregon, this single site is a red-hot warning to resist the nativist violence and ideology that drives anti-immigrant campaigns. It’s happened before, and it could happen again unless the racists are smashed and a vision of a better world raised in place of their jingoism.

Leaving John Day I drove up into the Aldritch mountains, high up in sweet-smelling afternoon spring air to the Cedar Grove botanical area. The forest of these mountains has a dry, high desert flora, pine and juniper shifting to fir at altitude.

I emerged from the glade and found a small stand of lousewort, which I often look for in spring to make a tincture for its gentle relaxing qualities. I quickly ate a handful of leaves to see if it would make me feel any better. It did. I shrugged and went back up the trail, stopping to photograph some mountain mahogany and a field of small native alliums, whose little white globes of star-flowers I snapped off and crunched for their oniony tang.

When I reached phone service again I looked up some info on the area and found that the mortality was in fact due to a backburn set by forest service biologists years previously. In attempting to save the cedar grove from an onrushing wildfire, the fire they kindled to clear fuels stressed the thin bark of the cedars to breaking point and killed the majority of the trees, old and young alike. Not precisely climate change then, but in the same pit with all of the other entanglements of cause and effect, and directly tied to a management ideology that can never take into account as many variables as its algorithm would like.

I drove on, through Dayville, and up through the Sheep Rock unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. This part of Oregon is deeply surreal, with loamy green hillocks of weird fossil-filled clay lurching out of the sagebrush, and gullied scablands chasing each other around the vivid green of the irrigated river-course. Sheep Rock itself is a marvel of erosional geology, wearing a node of newer flood-basalt like a jaunty cap atop its sedimented layers of ancient sea and lake beds.

The road wound over and on through the cantilevering sunshine, and at 6:30 I found myself in the town of Fossil, digging into the municipal fossil beds behind the High School (Go Panthers).

The High School provides a pile of old hammers and chisels for the visitor to use, and I hacked into sediment until I turned up a handful of ancient ferns. The dry hills stretched to all horizons and I turned the slabs of ferny rock in the sun, walking back over the green of the football field to the car. The ferns made me feel better about the cedars, better about the wilderness, better about the fate of this society. Notes scribbled into a geological notebook, buried alive, sleeping peacefully and valueless.

From there it was up to the tawny flanks of the Columbia Plateau and the long ride back through the darkening Gorge.

Lovely writing, Roger. Thanks for sharing this.

Thanks Helene.