This is an essay written by Eric Triantafillou that is included in Paper Politics: Socially Engaged Printmaking Today. Eric wrote the piece as a provocation to political printmakers, asking all of us to think deeper about what we do, and question whether it is accomplishing the things we think it should or we want it to. I find it challenging and valuable, and want to post it here in hopes of starting a broader discussion. Please give it a read and chime in. I know a number of artists that have read it and have questions and conflicts, so here’s the place to raise them!:

All The Instruments Agree

Eric Triantafillou

The façade of a now-defunct police station in San Francisco’s Mission District is plastered with street art. It is a visual cacophony of posters, flyers, stencils, paintings, drawings, and the hand-scrawled responses of passers-by. A remnant of the housing struggles that began in 2000, today this wall is a public commons that transmits information about everything from legal rights workshops to communist party meetings and yoga classes; also occupying its surface are corporate ads cloaked in DIY lino-chic. It is also a screen onto which people project thoughts and feelings about the world they fear and visions of the one they want.

From a distance, all these competing images and ideas side by side create an uneasy harmony, like a Jackson Pollock painting—a kind of abstract social expressionism. Up close, reading the messages, you see a lot of contradiction and tension, evidence of the wall’s messy and contentious evolution. The tactile beauty of the wall is immediate, and yet you realize that this wall is not just a space; it also reveals a history—it is a process in time. But what kind of process? Is the wall a representation of a public and participatory experiment, or its actualization? Is the wall a truly democratic space in a society that only claims to be democratic? Do these disparate images and contradictory ideas illustrate the diversity of our social, cultural, and political perspectives?

We could view this form of public communication not as constituting a consensus, but as proof that we can have dissensus and yet still coexist. After all, no one has to listen to or agree with anyone’s opinions; they simply need to tolerate them being expressed. Any idea, any image, can simply be covered over by another, ad infinitum. We could celebrate the wall as a bastion of diversity and dissent, a toehold in a society whose public space is increasingly privatized and controlled. But we also have to recognize that the wall can represent a norm for controversy in a society that has not found a way to resolve its conflicts, a society that easily recuperates the meaning of experiments like these and then sells them back to us as aesthetic commodities.

The book you hold in your hands is also a kind of wall. At one time or another, many of the images in this book have appeared in public spaces across the U.S. and other countries. Like layers of time, these images have been peeled off the palimpsest and placed next to each other on the page. These juxtapositions are both powerful and problematic. Like the wall in the Mission, this book represents a diverse cross-section of ideas and practices that together form a loose aggregate that we could call “left political art.” However, viewing all these images next to each other can give the appearance of political unity when there may actually be none.

As printmakers, most of us produce our work with an understanding that we are contributing to and continuing the tradition of politicized printmaking that Deborah Caplow discusses in her essay—a tradition that began with Goya in the early nineteenth century. I often think that we are more preoccupied with continuing this tradition than with asking why the promise it holds out—the promise of universal emancipation—remains so elusive. Our need to be constantly busy, to always be making more, is endemic to the activist compulsion to keep a movement alive, with little sense of what we are moving toward or why. I would go so far as to say that we, the producers of images that are meant to represent social conflict and its antidotes, may actually be complicit in prolonging, as opposed to fulfilling, this broken promise. How could this be?

The graphic art of dissent over the past century and a half is an endlessly twisting, impossibly varied, and fantastically inspired and inspiring maze of imagery. Yet within this multiplicity of signs, symbols, and slogans there are clearly many that are used again and again. The images of past struggles comprise a kind of inventory of left visual tropes that are continuously recycled. New generations of makers adapt the images of previous generations to the social conditions and aesthetic sensibilities of the present. This is in part what it means to operate within a tradition. Images of the past are re-used in order to commemorate them, to create symbolic continuity, to inspire new social movements with the knowledge that they are rooted in the past, to prevent historical amnesia.

Left graphics regularly portray the relationship of social forces as a conflict between two sides: Us—children crying, clenched fists, crowds amassing, plants growing, doves alighting—versus Them—bombs falling, smoke stacks spewing, barbed wire, prison bars, skeletons. In nineteenth-century France, left political cartoons frequently characterized the bourgeoisie as a parasite that sucks the blood of the workers. Many early anarchists and socialists believed that if the workers—whom they believed produced all the wealth—could rid society of the bourgeoisie, they would finally be free. In the history of left political art, this opposition is played out again and again in expressions like “Capitalists need workers, but workers don’t need capitalists.” It is probable that in a society in which workers controlled production there would be a more equitable distribution of material wealth. But I don’t think it helps to think of capitalism as something that some people do and others don’t. We are all subjects of the same socioeconomic system. The captains of industry and finance are no less dominated by this system, regardless of the fact that they benefit more, than the billions of people with far less. We are all bound to a system characterized by a blind march toward profit, one that must constantly revolutionize or perish.

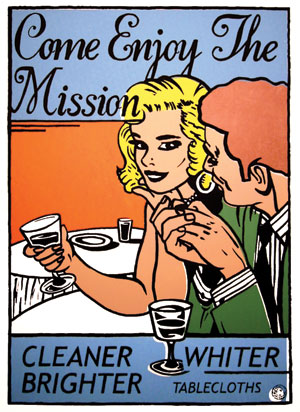

Cleaner, Brighter, Whiter Tablecloths only mirrored the way things appeared on the surface: young, white, urban professionals move into a “Latino” neighborhood, driving up real estate values and disrupting the sense of community. This conception reinforces the idea that capitalist society operates and can be understood through binaries like gentrifiers versus indigenous residents. What gets lost is the understanding of gentrification as a consequence of a socio-historical dynamic that shapes the actions of everyone involved: the venture capitalist who invests; the politician who frames the change as the natural course of economic development; the planning commission that rezones the neighborhood to pave the way; the banker who lends; the property owner who borrows to flip a condo or the first-time home-buyer who takes out a mortgage she can barely afford; the developer who controls the building trades or the independent contractor who hires cheap immigrant labor; and the community coalition attempting to get a temporary moratorium on the construction of market-rate housing so a few lower-income families can stay in their homes a little longer. The image of colonizing yuppies in search of authentic cultural interaction flattens this complex set of actors and interests into an easy-to-digest call to action. The more complex challenge of addressing gentrification and anti-gentrification struggles as systemic, as part of a process in which capital moves in and out of the built environment—the spatial component of capitalism’s necessity to continuously accumulate and expand—is something these symbols cannot communicate, and, in fact, obfuscate.

What is driving capitalism’s imperative to continuously accumulate value and increase that value? Is it old-fashioned human greed or something else? Why does gentrification specifically, and capitalism more generally, appear as a struggle between two opposing sides? Exploitation and social conflict are real and ever-present. But the socio-historical dynamic that structures all relationships, a dynamic that has become increasingly abstract over time, is concealed when it is understood through simple oppositions. This dynamic is rooted in the contingency and symbiosis of all social forces, classes, and interests. To reduce it to a conflict between good and evil does not help explain how this dynamic mediates social life, its origins, or how it has changed over time.

If we continue to express our politics as either choosing to do good or choosing to do bad, we will continue to think of the problem as one of being, as something in us, and not as a relationship between us. Good decisions by good people do not alter this dynamic in any fundamental way. Our focus on the ethical or unethical character of capitalist development, expressed in symbols of altruism versus greed, implies a politics of technocracy (an increase in social services here, a tighter regulation there), but also has the effect of closing off possibilities for more radical politics. Reform that ameliorates immediate material conditions strengthens the dominant thinking that our socioeconomic system is fundamentally sound, that it just needs some tinkering around the edges.

What if our images could do more? What if they had the potential to be radical, to go to the root, to try to represent the relationship that is hidden behind the binary idioms of our tradition? What if we were able to know what determines, and to clearly express, that which is truly wrong with capitalist society? As negative as our thinking and our images might become, they would point toward what is right and better.

At the same time artists are working through problems of representation, we must also think about how we produce images. What are the contexts in which our images are made? Who are the images for? Are they just preaching to the converted? If Cleaner, Brighter, Whiter Tablecloths was problematic as an image, the context in which it was made—as part of a larger effort to mount a visual response to what was happening in San Francisco’s Mission District—had far more potential. In 2000, some fellow printmakers and I began making posters about displacement and evictions. One of the places where we put them was on the old police station wall. Our group, the San Francisco Print Collective, became the propaganda wing of a neighborhood coalition that had come together to fight gentrification. SFPC members were united by the idea that art is an incredibly powerful tool when rooted in a social movement. We didn’t always agree with the political positions or tactics the coalition adopted, but we shared a common goal. The SFPC’s images and messages were composed by multiple voices within our collective, but when they hit the streets they spoke with one voice. Our work’s constant visual presence in public space helped communicate to others what was happening in the neighborhood. It also inspired and motivated people in the movement, inextricably linking our effectiveness and longevity to the wider community’s struggle.

Artists of the past organized large-scale unions and popular fronts in response to the social conditions of their time. Although these forms of organizing shouldn’t be ruled out, they haven’t materialized in the present. Many artists already work in small collectives, organizing themselves around shared affinities, social values, mutual support, and resource sharing. This doesn’t mean that as artists we automatically share a common political vision because of our backgrounds, a certain temperament, the media with which we work, or our relationship to other social actors and institutions. But what if we did? What if, instead of letting this book or the Mission District wall represent our differences—our pluralism—we began to work towards articulating a shared commonality?

I advocate that we, left printmakers, develop a set of shared goals, and use our powerful ability to intervene in public space, to create new ways of thinking and new meanings that refuse the dominant ones, and to develop tactics that can help us achieve those goals. The voices in this book and on that wall give the appearance of unity, of a unified opposition to capitalist society. But on closer examination, you can see fissures, fractures, and contradictions. If we began to organize ourselves, to create spaces for collective reflection and political education, I think we would find that ideologically we are very atomized, and that many of us would rather remain this way because the concept of unity (and all the past failed attempts at it) means a loss of individual freedom.

The collective articulation of a set of goals (which in and of itself would be an incredible undertaking) would necessitate an in-depth analysis of all the practices we’re engaged in. It would mean that we would have to confront the fact that some ways of thinking and some practices are probably better than others, as instruments for achieving our goals. This doesn’t mean it is wrong to make images that advocate that we “Support the troops, send the politicians to war” or “Knit for the revolution.” But it does mean that if these are the kinds of stories we tell ourselves and we attempt to fashion a politics out of them, we may not be getting any closer to our goals. In their broadest sense, these goals would have to involve creating the social conditions in which someone’s desire to make whatever she wants, to think and act as she sees fit—without being dominated by time, space or someone else—will have been gained for all.

The wall insists on an encounter. It wants to be used. But it is a space that gestures toward something beyond itself. It is not an end. It is a process of becoming. At the same time we create spaces of dialogue and public commons, at the same time we continue our tradition as the archaeologists of dreams and the farmers of inspiration, we can realize the force of unity that lies dormant in our fractured and individualistic practices. Let’s investigate our own thinking. Let’s look at our practices. Let’s collectively reflect on the images we make, and how and for whom we make them. Let’s ask if they could do more—if they could reveal the abstract barbarity of our social reality, and still incite and inspire us. As long as our goals are based on an intransigent desire for total social freedom, we have nothing to fear.

Eric Triantafillou lives in Chicago where he teaches and writes. He cofounded the San Francisco Print Collective and Mindbomb, a collaborative political activist art group in Romania.

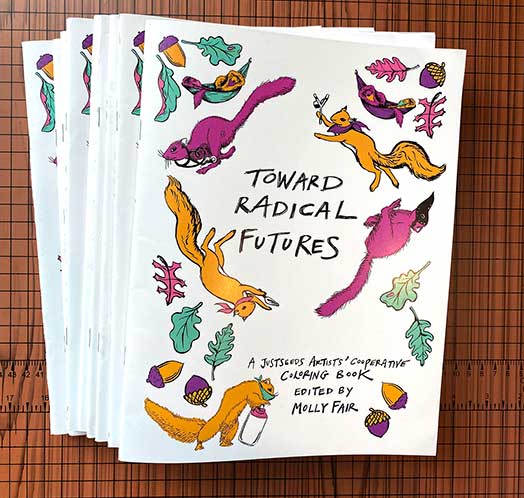

If you are interested in the book this essay came from, which includes two other full length essays, 200 color reproductions of political prints, and a dozen short pieces of writing by printmakers, please check it out HERE.

Eric raises some serious criticisms of current propaganda practice. He bursts the “feel good” bubble of simple creation and sharing of agitational images.

“However, viewing all these images next to each other can give the appearance of political unity when there may actually be none.”

And later on,

“I think that we would find that ideologically we are very atomized, and that many of us would rather remain this way because the concept of unity (and those past failed attempts at it) means a loss of individual freedom.”

“But I don’t think it helps to think of capitalism as something that some people do and others don’t….We are all bound to a system characterized by a blind march toward profit, one that must constantly revolutionize or perish.”

“But the socio-historical dynamic that structures all relationships, a dynamic that has become increasingly abstract over time, is concealed when it is understood through simple oppositions… To reduce it to a conflict between good and evil does not help to explain how this dynamic mediates social life, its origins, or how it has changed over time.”

His solution is to become better organized and politically aligned:

“I advocate that we, left printmakers, develop a set of shared goals, and use our powerful ability to intervene in public space, to create new ways of thinking and new meanings that refuse the dominant ones, and to develop tactics that can help us achieve those goals.”

I think that this call to arms is basically accurate. After all, who can argue with the increased political impact of a dedicated, politically sophisticated, organized cadre of propagandists? I worked in a political print collective for almost 20 years, one with an articulated political points of unity and deep connections with the community. I _know_ that this is one of the best approaches to socially-engaged art. However, let’s be honest, it also can be a huge amount of work and emotionally draining.

But let’s step back a bit. Who’s the driving force of history here – artists? Sure, we’d like to think so, and sometimes, some places, it may even be true. But we are but one of many revolutionary parts. It’s a tall order to expect that even the best of posters can “help to explain how this dynamic mediates social life, its origins, or how it has changed over time.” Especially in the United States, especially now.

The missing component of this is how artists – even dedicated, politically sophisticated, organized propagandists – engage with, and help build, the larger political groupings that fundamentally transform society. Unions, parties, mass movements, others. This dynamic, this dance between artistic subservience to “real” social movement organizations and the wet dream of cultural leadership at the forefront of revolution, is an ever-changing target, and worthy of many reasonable approaches. History has a lot to teach us about this, and that’s been the focus of my own practice recently. Deborah Caplow’s essay in the book touches upon this issue, but wasn’t written as a challenge to practices as Eric’s piece was. Organizing artists is important, but we can’t just talk about effective artmaking as a process unto itself.

I’d really like to know what others took away from the essay. I thank Eric for writing it, and hope that this leads to some interesting discussions.

Before responding to Eric’s post, I should preface my writing by noting that Eric is a good friend, someone I like immensely and someone I disagree with often when it comes to art, politics, and strategy.

Eric’s approach with this essay is on par with many of his other writings on political art. He lumps all political graphics on the left (and in Paper Politics) into a singular category (as anti-capitalist) and then critiques them for failing to adequately critiquie and challenge capitalism.

Yet, this approach does a disservice to the intentions of the specific art in question and the movements that they belong to. Each work of art has its own history and these histories are often missing from Eric’s critique. For instance, a gay pride poster is not necessarily anti-capitalist. It could be a response to a homophobic culture and a means to assert and celebrate one’s sexuality. You would have to ask the artist. A Chicana/o poster/graphic may have a class analysis, yet it may not. It might be about combating racism, celebrating ethnic pride, or informing an audience about a specific struggle. In essence, it can be about many things. It simply depends upon the artist and the issue that she or he is addressing. Divorcing it from its history to serve the intentions of the author makes the essay far less useful and far less accurate. It would be like lumping all the Civil Rights Movement posters and photographs into a category of being anti-capitalist and then critiquing the work (and the movement) for failing to topple capitalism. That line of thinking negates the history, the goals, and the many of the successes of the movement itself.

What depresses me about Eric’s writing is that he is often far too pessimistic of what art can and has done in social movements. Ironically, I enjoy his art (his work with the SFPC) much more than his criticism. Yet, he goes as far in this essay to critique his own image (Cleaner, Brighter, Whiter, Tablecloths) for not adequately communicating the root causes of capitalism. Thus, his image, and others that do not address this topic, fail to create much change.

I would disagree. Art creates change in many ways—some that are difficult to measure. Most of all, we should embrace a multiplicity of tactics in art (and activism). There is not the perfect image. Some images do “map” economic/political systems and they are important, but this isn’t to say that images that do not follow this route are not important. Images can express personal feelings. They can inform and agitate and still be very useful. They can pull people into movements. Inspire people and show opposition. At times, images can play a huge role within a movements (the AIDS movement, the IWW,…) Other times, images can be less pronounced within movements, yet they are still very much needed. For art is part of the conversation, not the entire conversation.

Eric’s call for unity and his call for shared goals (?) likely derives from his deep frustration from living in a capitalist society hell bent on war, profit, and ecological destruction. Many of us share these same frustrations, yet tearing down artists and their role in movements is not productive—especially if the critique sways so heavily towards the negative. If anything, artists need more encouragement, more respect for their work, and a greater place within movements and society.

Eric briefly touches upon this point. He states “SFPC members were united by the idea that art is an incredibly powerful tool when rooted in a social movement…. Our work’s constant visual presence in public space helped communicate to others what was happening in the neighborhood. It also inspired and motivated people in the movement, inextricably linking our effectiveness and longevity to the wider community’s struggle.”

I would agree.

I would disagree with Eric in his conclusion that artists (left printmakers) should have a “set of shared goals.” For one, this is impossible. “Left printmakers” represent people from all over the world and a shared goal likely does not exist unless we are forced to work under the Dictatorship of the Proletariat. Likewise, why have a movement with just artists. That makes no sense.

My thoughts echo Lincoln Cushing’s critique when he states that artists can “help build, the larger political groupings that fundamentally transform society. Unions, parties, mass movements, others.” Artists can do this by being directly involved in movements, yet we should not negate the power of artists also simply generating culture. Politics and movements change the world, but so does culture.

In closing, let us not over-generalize these huge issues. Let us not divorce art from its own histories. Finally, let us not over-generalize the untold impact of art within social movements.

Thanks for these responses Lincoln and Nicholas.

Neither of you address the central point I make in the essay, so I’ll re-state it:

The images we make, images that are meant to represent social conflict (and its antidotes), may actually be complicit in perpetuating, as opposed to revealing, the nature of this conflict. This is in part a formal issue. I’m saying that I believe the forms we use to symbolize or represent reality are inadequate to the complexity of that reality. They tend to obfuscate rather than elucidate the increasingly abstract character of capitalist society.

I believe that what we call art is increasingly used an instrument for expressing symptoms. It is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain a sane level of psychosocial functioning in this world. Aestheticizing these feelings is a way of externalizing the deep sense of alienation and fragmentation we experience everyday. These aestheticized feelings, these objects, become cellular components of a large, complex, dynamic system that encompasses people and things and which is directed toward one goal, production for the sake of production. I want us to throw light on this dynamic.

I’ll address some of Lincoln’s points first…

“Who’s the driving force of history here – artists?”

“Organizing artists is important, but we can’t just talk about effective artmaking as a process unto itself.”

I’m not saying that artists are the driving force of history, that artists have a special role in the process of social change, or that we should think of art making as a process that is somehow isolated from other forms of labor and social contexts. The reason I bracket artists (printmakers in this case) is because of the specific media we use (symbolic communication, reproducibility, public dissemination) and how that media lends itself to political intervention and social movements. There are formal qualities that printmaking and graphics production have that set them apart from other media and other disciplines. This doesn’t mean that we ourselves or the tools we use are separate from other social actors and organizations. It just means that the questions we ask ourselves are different from someone who works in agriculture or healthcare.

“It’s a tall order to expect that even the best of posters can ‘help to explain how this dynamic mediates social life, its origins, or how it has changed over time.’”

I agree. It is because political graphics communicate with symbolic and representative forms that they are limited in their ability to explain complex issues in the same way that a book could. These formal limitations are one of the reasons why I believe we need re-think how we make images and not simply rely on their default mechanism as culture that raises consciousness.

“The missing component of this is how artists – even dedicated, politically sophisticated, organized propagandists – engage with, and help build, the larger political groupings that fundamentally transform society.”

Part of my argument is that we should not take for granted what it is we do (i.e., that we make images that tell stories, communicate ideas, feelings, etc.) and simply see the problem as one of organizing (i.e., how do we connect with movements to harness the power of art in shaping social change?).

Now on to some of the points Nicholas makes…

“Eric’s approach with this essay is on par with many of his other writings on political art. He lumps all political graphics on the left (and in Paper Politics) into a singular category (as anti-capitalist) and then critiques them for failing to adequately critique and challenge capitalism.”

I will confine my comments to the work in Paper Politics and not address, as Nicholas does, my “other writings,” since they are not part of this discussion.

I use the category of anticapitalist because this is the way I interpret the images in the book. Nicholas mischaracterizes this as an empirical fact, when it is a conceptual framework that I use to structure an argument.

Is it really such a stretch to claim that the images in PP express ideas that could be interpreted as anticapitalist? I think you’d be hard-pressed to find someone in PP who does NOT identify their politics, on some level, as anticapitalist. I don’t think it’s necessary that a person or movement explicitly state that their politics are anticapiltalist in order to see in them elements or aspects which can be understood to be against capitalism. I use anticapitalism as a critical category, not affirmatively. For me, it’s a broad term to denote a wide set of ideas and practices, some of which are deeply reactionary and conservative. For example, the burgeoning Tea Party movement in this country has some ideas which are clearly anticapitalist, even though they might not use the term. The Nazis and Al-Qaeda are other examples. There are many.

That each poster is a particular expression, with its own intentions and motivations, is self-evident. Categorizing them as “anticapitalist” does not flatten this specificity or the unique history of each poster any more than calling them “radical” does.

“…he goes as far in this essay to critique his own image (Cleaner, Brighter, Whiter, Tablecloths) for not adequately communicating the root causes of capitalism. Thus, his image, and others that do not address this topic, fail to create much change.”

When I critique my own poster, I don’t say that it failed “to create much change.” This is another mischaracterization. I don’t believe there is a direct causal relationship between an image and social change. No single image has that power. My point is that Cleaner, Brighter represented a relationship that was concretely real (white yuppies moving into a predominantly Latino neighborhood), and yet it only portrayed the surface of that reality, what we can immediately see, while doing little to indicate the complexity of the social historical dynamic that gentrification is a part of. I believe these simplifications, though inspiring, cause more damage than good. They delude us into thinking that social conflict is an us/them paradigm. This may be good for short-term political organizing because its helps polarize the problem as one of sides, makes us comfortable to feel part of a side, always the good side of course, but it doesn’t push us to consider that social reality is far more complex than choosing the right side. I suppose we could all throw our hands in the air and simply say it can’t be done, that this is too much to ask of ourselves and our medium. It seems that’s what Nicholas would have us do.

“What depresses me about Eric’s writing is that he is often far too pessimistic of what art can and has done in social movements. Ironically, I enjoy his art (his work with the SFPC) much more than his criticism.”

Another way of putting this is: If you don’t have anything good to say, don’t say anything at all. This strikes me as the liberal ideology that dictates that if you’re going to say something negative you’d better also say something positive. That way we can say it’s a balanced and fair, there’s a democrat on one side and a republican on the other. I’m not concerned with whether you “enjoy” the article or not. My primary desire is that the claims be taken up, or not, on the strength of their significance.

“I would disagree with Eric in his conclusion that artists (left printmakers) should have a “set of shared goals.” For one, this is impossible. “Left printmakers” represent people from all over the world and a shared goal likely does not exist unless we are forced to work under the Dictatorship of the Proletariat. Likewise, why have a movement with just artists. That makes no sense.”

Why is it that when the idea of something shared or common is invoked it immediately raises the spectre of Stalinist universality? Why is Nicholas’ vision backwards to the failings of history? When I call for a shared set of goals I certainly don’t have a Dictatorship of the Proletariat in mind. I have no idea what a shared set of goals might look like at this moment, only that I believe it to be a necessity. Nicholas says a set of shared goals is “impossible.” Why? Are we really so fundamentally different? Are those of us who believe that the capitalist system dominates human beings and want to create a society in which no system, individual or group is dominated by or can dominate another really so different? What is the point of making a poster that expresses solidarity with the Zapatistas if not to link our struggle with theirs, to illustrate that we share a common struggle, even though our concrete circumstances and social conditions may be very different? Has our desire to articulate our differences so colored our vision that anything, even the mention of something shared or common is immediately associated with oppression and death? And you call me a pessimist?

I’m not advocating that we build a movement of artists. As Nicholas says, that would make no sense. I’m suggesting we create sites and structures for us to begin to collectively share and discuss the ways we interpret and think about the world we live in and how these thoughts and feelings are externalized as images. It’s obvious that our work is amazing at expressing affective qualities like anguish, alienation, despair, hope and inspiration. I believe that as real and important as these feelings are, they rest on the surface; they are what we can immediately see, they are the symptoms of a malady, not its cause, and conversely, not it’s solution.

We cannot measure all the ways our work functions in the world, how effective it is. Effective at what? This is why the issue of shared goals is important, not the goals of the individual work, but the work’s relation to the goals of a collective vision, beginning with the vision of those closest to us, those with whom we share a form of labor and discourse. Asking whether or not an individual piece of work is effective is a bit of red herring. This is the result of a society whose divisions of labor have so permeated every aspect of life that we require of all human processes that they prove their value in the technocratic chain of social reproduction. Social movements are not immune to this thinking.

But asking how effective our social movements are is another story, and our collective work is implicated in this question. How can we ever truly know what an individual work is doing? We can only guess. This doesn’t mean, however, that we can’t try to make them do more, to push past the surface and into the Matrix. This is all I’m asking.

“…we should not negate the power of artists also simply generating culture. Politics and movements change the world, but so does culture.”

“…let us not over-generalize the untold impact of art within social movements.”

It is precisely these types of vague platitudes (“simply generating culture”) about the power of art and its role in social movements that I think we should be questioning. Contrary to what Nicholas claims about the importance of the specific histories of individual works, he doesn’t seem to be interested in how that specificity is related to social transformation, only that it is. Rather, he seems to want to leave this thing called art alone, untouched, mystified, and just say how great it is and that we need more of it and to support those doing it.

Simply historicizing a work of art is not enough. We must seek to understand how the conditions in which it is produced are bound up in its forms and how its content, its message, is related to but not identical with this form. We have to interrogate the category of art (as a form of labor, and as generative of a symbolic dimension, i.e., the ability to create pre-figurative spaces, imaginaries, utopias) as it relates to politics and social transformation. But we need to do this by looking at the specific forms that are used in art, its signs, symbols and slogans, not its “untold impact.”

“…tearing down artists and their role in movements is not productive—especially if the critique sways so heavily towards the negative. If anything, artists need more encouragement, more respect for their work, and a greater place within movements and society.”

Our place in social movements is commensurate with our ability to make what we do as relevant as possible to the social conditions we all live in and our ability to see beyond them to something else—not from liberal demands for more respect and tolerance. Maybe the difference in our approaches could be characterized this way: Whereas Nicholas is here to kiss your ass, I would rather kick it. That includes my own.

Eric,

Great job. You have rejected nearly every critique of your article and turned the conversation towards absolutism.

Movements arise and flourish through a multiplicity of voices and tactics. I appreciate how you keep your eyes on the prize (capitalism) but I seriously question your tactics.

Stating that I kiss ass and embrace liberalism is verbal bullying and you should no better to engage in such pettiness.

Nicholas,

I have tried to seriously respond to your criticisms and would only ask that you do the same, which you do not. That you disagree with my tactics is fine, but could you please explain why on the basis of the points I make and not simply dismiss them outright as petty verbal bullying?

Again, you have stated what is self-evident as if you are laying some heavy truth at our feet. Who among us would disagree that “Movements arise and flourish through a multiplicity of voices and tactics.”?

It is difficult to see if this kind of relativism is a way to avoid taking up the points I make, and/or a way of dismissing them on an emotional level. Is it really then so difficult to see how I might perceive liberal ideology at work in your comments?

My comments are not directed at you personally, but at the ideas you express. This is part of my critique: that we make an identity between who we are and how we think, when how we think (our ideology) is deeply influenced by the social historical contexts in which we live.

I hope that we can continue to discuss the ideas that are raised. That way we can see what we share and what we don’t, without assuming anything simply because we are all of the Left.

Eric, and all,

Despite the tense nature of this dialog—it is productive. I dismissed too many of Eric’s points and (in my opinion) the tone of Eric’s writing is too combative. To me, it puts artists who make this type of work on the defensive, where I (an perhaps others) tend to dismiss some of his writing because positive reflection on the work is often missing. That said, I should take a deep breath and re-evaluate the criticism and his ideas in more depth.

We can all improve our work and our tactics so hopefully this dialog leads us in that direction.

Be great to see others post on Eric’s topic.

I appreciate this discussion, and the desire to work on our shared visual and symbolic language. And by ‘our’ I’m referring to people committed in some form or another to an anti-capitalist politics. This however, raises that pesky issue – that the grand NO (to capitalism) may only provide loose identification—maybe even temporary affiliation—for the many Yes’s that are not all or always compatible with one another. So where to from there?

This seems to be a rather big issue—a sticking point among and within various lefts—as to the relationship between shared goals, shared analysis, shared tactics, shared organization… and the lack/refusal/incapacity/disinterest in working towards such connections. This has only tangentially to do with art; it is about something bigger, with a long, sectarian, bitter, distrustful history chomping silently at its heels. I mean, tell me if I’m wrong, but is this essay a little bit of a call for the anticapitalist artists of the world to be communist like me?

Ooooooooooh… I said a dirty word.

But right under the veneer of art-critique this seems to be the core issue — reconciling various tendencies of socialist, communist, anarchist, left-liberal (sorry they are in the mix too, even if ‘they’ would never name themselves such) with one another, and trying to build out of this broader field a unified social production: an anticapitalist visual and symbolic vernacular. Here though, I think the essay is collapsing two different projects into one another.

On the one hand, there is art-critique: there are some good points about problems with some of the tried and true strategies of left symbolism, and this allegation that they “may actually be complicit in perpetuating, as opposed to revealing, the nature of this conflict.” Totally. Though in my own opinion, I would caution that this veers a bit too close to a rather one dimensional culture critique. Eric, you might critique your gentrification poster via Adorno, but I could just easily defend it via Brecht.

(Sorry to name drop. Basically, here’s my super simplistic version of the distinction: Adorno says we’re dominated by a culture industry where all creativity is filtered through capital’s commodity form and art becomes a ‘safety valve’ for society where radical thought can be expressed in an aestheticized realm that has been safely insulated from the political and economic – we aestheticize politics and end up with just one further level of commodity fetishism obfuscating reality. Brecht, on the other hand, says ‘yeah, I get it, capitalism sucks and mass bourgeois culture is a commodity orgy and means of social control—but I think I can make art that jars the bourgeois audience into recognizing the bullshit and thinking critically about the naturalized conditions of their oppression.)

The key here—I think—is that Brecht is a bit more historical in his analysis, placing art-making within a specific historical/social context. Brecht does not attempt to symbolically destroy capitalism by getting to the core of its truth-content, but to simply have a useful effect in the moment. That seems to be some of the criticism that this essay received, but I’m not sure I agree with the critics. I don’t think caricatures of Brecht or Adorno suffice. Perhaps these images each have their own history and likely have each been part of a process that Eric should not presume to understand or know or judge for its effect—sure—but that doesn’t somehow make them immune from critique.

This is something that bugs me, when the particularities of our difference become a shield to deflect attempts at critical reflection, a means of preserving dignity (and keeping that precious ego intact) by defending what was as what should have been due to the exigencies of the circumstance. Its like political bug spray. But isn’t it a bummer that we think of the critic as a pest? What about the good pests, like lady bugs, who eat off all the bad guys from your tomato plants (at least until they fly off into someone else’s yard)?

OK, so now the other hand—the other hand was about organization, building a shared symbolic/visual practice/vernacular/code. Eric wants us to come together, and I wont repeat what I said above, but I think all the resistance to this has to do with some serious differences in political philosophy amongst those participating in this dialogue. He gives us a story of his work in a propaganda machine (the San Francisco Print Collective)—and it sounds great. Truthfully. But does this story translate to the scale of his critique? That’s where I’m not convinced. I’d be curious to learn how the collective was organized? How were decisions made? How were images made? Did they go through various rounds of critique? Did multiple artists work on singular images (I’m guessing not—seeing as Eric comfortably called his work with that group, at least the one image he posted, ‘his’)? In other words, how did critique successfully filter through to practice within this one example of a collaborative artmaking group? (Or I suppose judging from his self criticism, how did it fail?)

One last random theoretical reference: Willem Reich. Another caricature: Reich tries to show how the authoritarian structure of the family reproduces/reinforces the social relations of capital—a critique that leads to some interesting conclusions — that the very ‘nature’ of our possessive lives, and the ways we inhabit the many rhythms of our everyday lives, are the stomping grounds of capitalist (and gendered, racialized…) social relations. So that said, I wonder if its worth reflecting on the sacrosanct category that goes unquestioned throughout this entire discussion: the individual artist-genius? Art made in a collective that is still named as ‘my’ art may in fact be where the reproduction of commodified relations are happening, no matter what the picture looks like and how clever its anti-capitalist symbolism. Just a thought.

But then to switch gears again, and defend Eric’s side a bit: The two commentaries seem more interested in celebrating cultural practice first, critiquing it second; more interested in understanding the art’s context, the people who made it, why they made it—and perhaps giving them the benefit of the doubt that they have a reason for doing what they’ve done, making what they’ve made, analyzing how they’ve analyzed…. It just may not be the specific analysis, reason, or approach that Eric prefers. This is a very generous set of assumptions that actually completely silences Eric’s critique, because within such a set of assumptions, there is actually no space left for the possibility that upon reflection, an art producer might say, ‘yeah, that image wasn’t actually so good or successful.’ And really—that’s at the crux of what Eric seems to be looking for.

This might seem tangential, but what this raises for me is a question of value. Not only the value that Marxists talk about when critiquing capital, but the possibility that there are, were, could, or should be other forms of value—other ways in which social wealth is produced and circulated throughout the social body. The issue, or disagreement, seems to be in the ‘currency’ of left, or radical, or anti-capital art.

As mentioned above, there are many different anti-capitalisms, yet the standpoint of Eric’s critique is one that presumes ‘we’ are anti-capitalist, and it seems his conception of what this means is rather particular. This might not be a call to form some union of radical artists, but it is a call in a similar univocal way—where you are presuming a singular, totalized and totalizing conception of what capital is—and then the only anti-capitalist politics to be valued is one that thoroughly understands this conception of capital and orients itself towards this capital’s concrete destruction. While I have sympathies with this critique, I also recognize that not everyone shares this analysis of capital and therefore not everyone is ‘anti-capitalist like us.’ There are different ‘left currencies’ circulating through our shared world, and no one hegemon controlling the situation. Maybe instead of trying to impose a gold standard we need to ask what a floating exchange rate would look like?

So here’s the jerkiest version of my question: Eric, is your frustration with the state of left art really about the imagery used or is it about the fact that reading through the three volumes of Marx’s Capital is not a prerequisite for silk screening? This is where I think some caution needs to be taken—there are some serious knowledge hierarchies being established here—most notably the relegation of affect to a lower order of significance, a veneer behind which real exploitation happens. What is this real exploitation? Where does it happen? How is it more material? More concrete?

This real exploitation is—I’m guessing (and actually, agreeing)—our violent reduction to abstract labor. Sure. But let’s not forget, the reduction to abstract labor happens to real people, whose real bodies (social and material) are thinking, feeling, living, emoting things. There is no reason that ‘anti capitalist’ art is less valid for expressing the anguish or violence of these dimensions of lived experience, and for you to proclaim that the standard for ‘good’ (read: effective, functional) radical art is its ability to move beyond this realm of feelings is absolutely an extension of a very (patriarchal) capitalist way of seeing directly through (rendering invisible) all those sorts of non-functional, non means-ends dimensions of human social existence. You would have the functional metaphor of art be a hammer, smashing through the walls of capitalist exploitation—whereas the metaphor implied by Lincoln and Nicolas is more like a watering bucket or a spade, nourishing left communities that art making is embedded within.

And then the communists roll their eyes, “ugh, so go make another community garden or something.” That’s not what I’m arguing at all. Personally, I think neither are sufficient, and to be stereotypically Marxist about it, maybe we need to ask what a dialectic between the two positions would look like. Nurturing and attacking—without unilaterally privileging either. So yeah, vague platitudes about the value of cultural production are not that helpful, but neither are abstract calls to leave the ‘surface’ and ‘enter the matrix.’ I mean, come on Neo, I saw that movie too. What are you going to do when you get into the matrix, have a big ninja fight with the evil capitalist virus and then fly off to the mothership where you can broker a reformist deal with God?

But maybe we can all agree that these conversations are, or at least can be, important? I hope so—and I definitely am learning from them. So thanks.

hello over there…

this might be a bit off the track, since a) i am writing from berlin/germany, b) because of my limitation in writing english, it’s a bit hard for me to relate 1 to 1 to the text above…, and c) because i am answering a bit late. but never the less i did enjoy reading eric’s text and the responses, because they—to a certain extent—touch issues and questions which i have come across in the last years in the field of visual communication and leftist politics…

here: i will only share some thoughts on posters. i will leave aside a lot of other questions which are on the table, which are in eric’s text and the responses, i.e. the questions on how to understand what the left is and what role “visual communicators” etc. could play in it…

i will basically share a few of my understandings of what a “good political poster” could be and what a few parameters on an abstract level (!) are for me. i am running into open doors -> i basically want to underline some of eric’s critique on posters and add a few thoughts.

first of all, we all know that calling a poster a “political poster,” is a self limitation in the first place. it implies that other “visual products” such as cultural posters, advertising posters, music posters, etc. are not political….and also it structures the reception of the so called “political poster” towards the (what one might consider) political aspect of the poster, the theme so to speak, and this can be a limitation.

there are of course many different contexts and aims where posters circulate. sometimes a poster just has to inform, sometimes it has to mobilize, sometimes it wants to reassure a certain group of people in their activities, and so on. these posters have to have different forms and also different visual communicative strategies. clear.

anyway > posters with clear answers “bore” us—nearly always! especially when they have exclamation marks in them such as stars, fists, breaking chains and walls, flags and skies, masses, and a “historical witness program” (tradition?) which proves “we” are on the right side of the story—of history, good and bad simplifications, etc…

thank you very much, but i am already converted.

even though i personally might like one or the other for their aesthetics, i don’t want to be bored by a political message in a form where i can only mark: yes! or no!

i want to be challenged with my eye and even more what lies behind the eye—and how this relates to my abstract and concrete understanding of how i live my life and where my engagement in society lies…

and of course i am a part of the problem, and i don’t always want to be the good guy or imagine myself as the good one.

since engagement exists not only in political struggles, but in daily life, i want cultural and political “products” which also deal with these realities and complexities. this is actually quite banal, but somehow we see very few posters which are not afraid to be a bit more ambivalent or complex with the content/images they put into this world.

we (me & my partner at image-shift.net) like posters which ask questions. which include the complexities and contradictions into the struggle and their visual representation, rather than reducing them to a self-reassured product, to a feel-good identity mirror. i don’t like sports fan shops either, i don’t need a mug with a red star on it to enjoy my morning coffee…

well, maybe some people (like myself years ago?) need these simplifications in order to identify, in order to relate to others, to a politically imagined collective? but we feel/know that identity politics are exclusive and a reduction of oneself in the end…. (“i am this – and not that”)

i believe the “we” construction is something which should be handled with extreme care! specially leftist visual producers have a responsibility not to create an untrue “constucted spectacle of unity and happy resistance world.” such a critique and approach does not prevent us from sharing our solidarity with others. we rather look for the problems than for unity. critique is solidarity in praxis.

posters which ask questions?

we are dealing with an undemocratic media here. the poster talks—you listen. this is the main communicative structure. so what could it mean to seek a gesture and form of dialog IN the poster design? what is a social image? a social image can be an image which triggers the relation between the recipient and the social, cultural and political context. it does not reduce politics to themes and issues and “isolated” struggles represented on a nice colourful piece of paper.

authorship?

is the individual speaking “authentically” when interpreting the struggles, forming it into an image…? we believe that the specific aesthetic gesture of one author (like illustrations) always comes back to him or her. this can narrow the field of possible communication. the story has been told to the end already by someone else (the artist). we think its good to things more relative, to push back authorship in order to privilege the content and how the communication is shaped. (is it an offer?, or an exclamation mark? a story or a sign? fast or slow? etc…)

for us the design process does not end at the edge of the poster, but includes the production circumstances, the distribution context (in small & large), and the audience into the understanding of how the communication is shaped here. the whole idea of the “political artist” is anti-emancipatory to us. it is potentially an anti-collective community setting (one person talks…) it is a fine line between talking with an individual gesture (“you could be this”) and abstraction (“this is for all of us”). to shape this edge without being pathetic, to include the existing contradictions of daily life in capitalist culture into our images would strengthen our visual language.

ok—as mentioned above, these ideas are intended to underline some of the points which where already raised above.

so far for now, all the best,

sandy / image-shift.net

ps – below are some links from our work to illustrate a little from where we are talking:

http://www.image-shift.net/EX_CMS/G8%20plakate/g8_posters.html

http://www.image-shift.net/CMS/index.php?page=150

http://www.image-shift.net/CMS/index.php?page=143&modaction=detail&modid=408

and actually this text by brian holms, tony creadland and myself from 2001 is touching some of the further issues here in the discussion: http://backspace.com/notes/2006/10/design-is-not-enough.php#more

flickr:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/37444004@N03/

Some good stuff coming out here. I do appreciate sandy’s comments, especially the point about the self-definition of “political poster.”In my defense of propaganda, I explain to people that we usually experience that genre as “commercials.” And if the root question of this discussion is “effectiveness,” their side has a very clean metric – improved product sales, usually on a very small time scale. Vast amounts of money are spent on creative artistic talent to…make more money. Still more vast amounts are spent measuring effectiveness before and after – focus groups, surveys, the works. They operate in a different league than we do.

Our side, on the other hand, has very vague and hard-to-measure metrics. Social justice? Income equality? Reduced racism? Not many posters can be really measured on their impact.

And there are different types of posters. Some try to do something more modest (“We are the retail clerk’s union and please don’t cross our picket” – which can be observed and measured) and others something more abstract (“Think about rainforest devastation when you buy that burger” or “Don’t capitulate to loss of civil liberties masquerading as enhanced security measures.”)

So, Eric, I think it’s very appropriate to ask that progressive artists be more “scientific” (yes, Jesse, it’s the Marxist in me leaking out) in thinking about what will likely happen to that poster before they make it, but I also don’t want to imply that only the “best and most effective” art is worth making. The dialectic between cultural workers and political activists is a legitimately dynamic one, and sometimes artistic approaches outside the norms of conventional propaganda prove to be the most effective ones.

Sorry it’s taken me a while to respond. Jesse and Sandy raise some good points. I too am learning and hope we can continue this conversation.

Reading Jesse’s post I was reminded of the ideological differences always lurking under the surface and of the necessity of making these as transparent as possible, of being as honest with myself and others as I possibly can. Then reading Sandy’s post I felt myself being pulled back toward aesthetic concerns. They are inextricably linked, but we have to divide them up to make sense of them. I guess my responses here are more on the political side.

I want to be clear, my interest is with the signs, symbols and slogans we consciously produce to represent the ways we think about our social reality. I realize these representations are bound up with a lot of other stuff we cannot measure, gauge, or even know in any conscious way. I have no interest in treading on the non means-ends dimension of anyone’s work or relegating affect to a lower order of significance. I don’t pretend to know how these dimensions function in the world, only that they do. And I’m aware that even propaganda has a non means-ends dimension. I’d like to let that dimension be for now.

My interest here is squarely in the didactic and instrumentalized realm of propaganda and how politics are expressed through social movement imagery. So, more toward Brecht. And though I’m sympathetic to the reasons Adorno locates the political potential of art in its aesthetic dimension only (art-for-art’s-sake pursuing its own internal logic to point out social contradictions), I don’t think retreating into purely aesthetic experimentation, in the absence of radical political possibilities, is the way to go.

I think of propaganda, political posters, etc., as a type of art that points to a purpose beyond itself, a purpose that will not come solely from a collective of artists, and yet, a purpose that artists can help articulate in the process of making work for and within social movements. In my opinion, that purpose remains incoherent in any political sense—among artists, and more generally. It sounds like a lot of people are ok with that. I’m not. And I’m trying to show some of the ways this incoherence is manifested formally, in the images we make, but also, as Jesse points out, that it is rooted in clashing political ideologies, and that we should not assume coherence (the concept of a radical left) where there is none. Maybe this incoherence is willful, maybe it’s understood as dissensus, a counter-principle to the dominant logics of consensus, a way through. I don’t know.

As Lincoln said, my essay is written as a polemic, as a deliberate attack on the way social movement propaganda is conceived of and produced, which it seems to me is more out of habit than anything else. This is not an attack on any one individual, their feelings, or the way these feelings are manifested in their art. I believe we can be ontologically different and yet share common aims, goals, purposes, and find ways of realizing these goals collectively. Part of how we think and act (our politics) can be as an instrument for another world. That is why I titled the essay “All the Instruments Agree,” and not “All the People Agree.” I realize, even in our capacity as instruments, we don’t all agree, but my hope is that we can maintain our differences and still move toward articulating common denominators.

I recognize that we have different political perspectives. My own inclination, which was not an epiphany but rather, developed gradually over time, is to develop an anticapitalist revolutionary movement in this country. Radical autonomy is certainly the only way I can think of doing this, but it’s not likely to go very far unless anticapitalists organize themselves as a collective force, and I think art can help do this.

It seems like the rub for many artists is this thorny issue of instrumentality. In our desire to maintain as much autonomy as we can (to feel free in an unfree world) we have developed an understanding of politics, expressed through our art, as a non-instrumentalized practice. Yes, instrumental reason—the means-ends dimension—is essentially a capitalist (and often is but doesn’t have to be a patriarchal) form of reason. Jesse is right about this. But this doesn’t mean instrumentality can be avoided. Wherever there are aims and goals, there is instrumental reason. A non-instrumental struggle would be one that has no aims or goals, that doesn’t care whether it succeeds or fails. If a struggle has aims and wants to realize them, then it is entangled with instrumentality.

I think Jesse’s right to caution against collapsing art critique into political critique, art has its own internal logics. But for many artists in Paper Politics, art and politics seem to be the same thing. Dylan Minor states this pretty clearly when he says (p. 130): “I see my art-making practice as the embodiment of my politics.” I think this is why artists often respond defensively when someone levels a critique at their politics. If who they are is so bound up in their art, and their art is their politics, then a critique of their politics is seen or felt as an attack (a form of violence) on their ontological being.

Sandy alludes to this problem of making an identity between social being (who we are) and consciousness (how we think), in one of the posters he has online: http://www.image-shift.net/CMS/index.php?page=150&modaction=detail&modid=381. It talks about gender and sexuality, but it could just as easily be about art or politics: “What if we were to stop saying “I am…” and started to say, “We want to become…”? And why is it so much easier to pose questions like these, than it is to enact them in our daily practice?” Yes, a politics of becoming, one that doesn’t force an immediate identity between what it is and what is thought, but can always be moving toward reconciliation, an identity between the two. This would amount to a new conception of politics, one that if we took up, would change the way we make images.

At present, left political organizing seems content with pluralist/social partner constellations that fall roughly along the same lines as the divisions of labor and identities (class, race, gender, sexuality, etc.) in our society. Is it really so difficult to imagine that there could be a set of values and even goals that these disparate groups might share? I’m not saying that all of them, or even the minority, identify as anticapitalist. But they certainly share similar critiques of capitalist society, some of which seek important reforms, but others that are clearly at odds with its fundamental principles. Even if we accept, as Jesse implies, that there are as many interpretations of capital and not one totalizing one, this still leaves us in the lurch. I don’t understand how a “floating exchange rate” of left currencies would be any different than this status quo.

I realize that I might be asking instrumental art (political graphics, posters, etc.) to do more than it is capable of. Maybe I’m putting the cart before the horse. Maybe the kind of instrumental art I’m envisioning first needs a collective emancipatory vision and a shared strategy for how to achieve that vision. Brecht’s art had that vision. Unfortunately, it remained hitched to Stalinist socialism.

It is because I believe in the power of our art to open up spaces for seeing beyond what is to something else, to pre-figure another reality (critically, not affirmatively) that I think we could help articulate, if not the content of an emancipatory politics, at least its necessity, and ground that necessity in a collective process. I believe that what a lot of our art does now, and I do not recuse my own work from this critique, actually perpetuates the problems it aims to overcome for the reasons I state in the essay. It seems like Jesse, Sandy, and perhaps some others agree with this component of the critique. Maybe we should start there.

What I’m advocating is infinitely more practical than fighting ninjas in the computer-generated matrix, although it will involve some jousting.

I’m asking that we (social movement printmakers, self-identified oppositional artists, the artistically inclined but socially disenchanted, those experimenting with expression as communication) create spaces and venues to come together periodically to look at and discuss that component of our work we consider propagandistic; to share our conceptions of social reality and how they make their way into our imagery; to discuss our own politics and how they link up (or not) with the social movements we work for/within; to open ourselves to critical reflection from others; to nurture and cajole one another; to recognize that hierarchies of knowledge exist and must be made transparent but that political education doesn’t have to mean imposing a hegemonic “gold standard” on anyone; to be critical of and not simply affirm the failure of concepts and ideas because they were associated with bogeymen and mass graves in the past; and even to accept that some tools may be more useful than others for helping us understand how society works.

Yes, a Marxist historical materialist methodology may be one of those tools. But it’s just one, there are many. Anything that helps us move, dialectically not absolutely, from perception (looking at, feeling and expressing reality) to conception (analyzing and thinking about how to change it) is a potentially powerful tool.

Maybe if I threw another log on the fire we could rekindle this thread? Here’s a recent piece I wrote about Paper Politics for the Brooklyn Rail:

http://www.brooklynrail.org/2010/05/express/printmaking-as-resistance