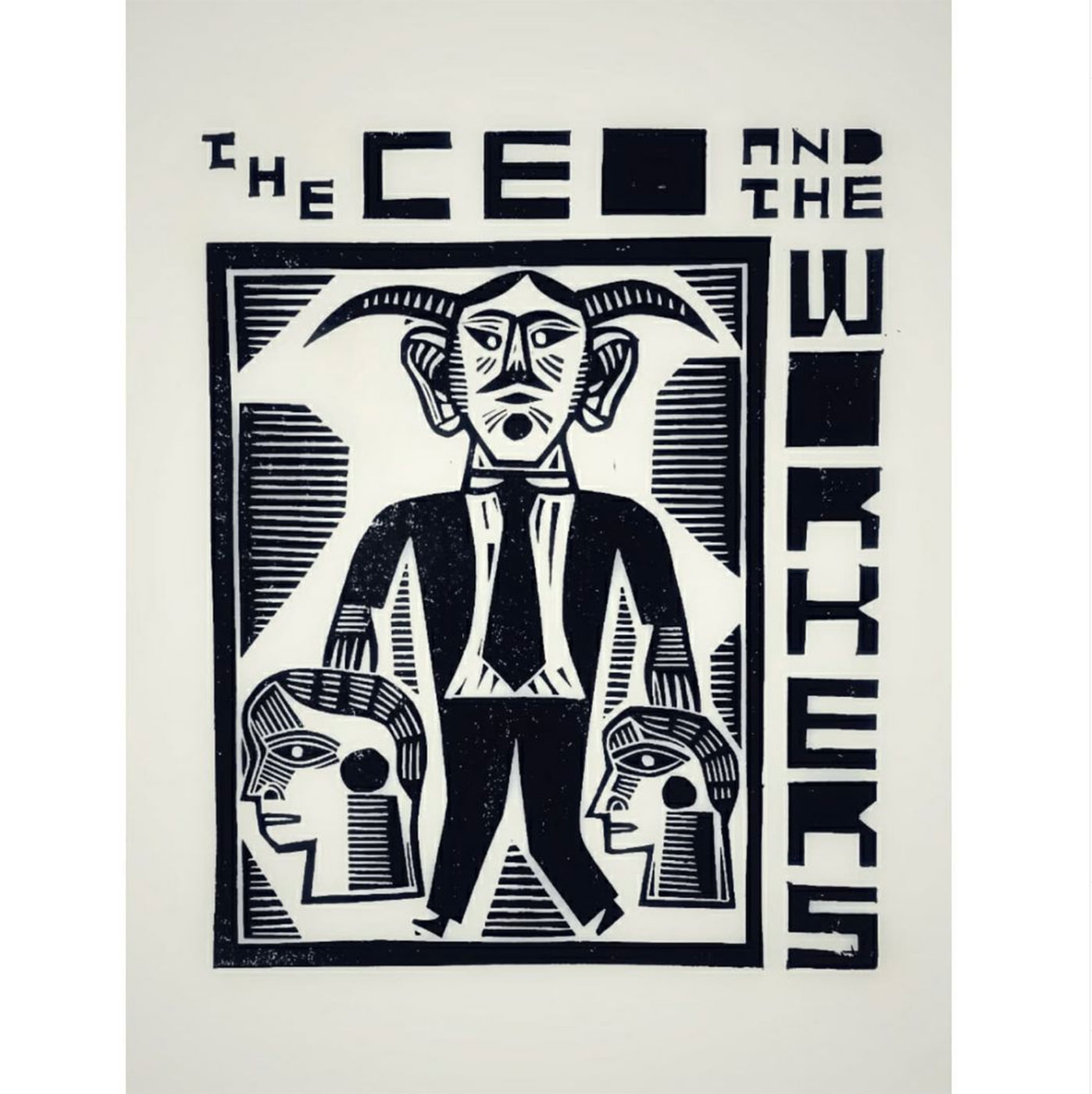

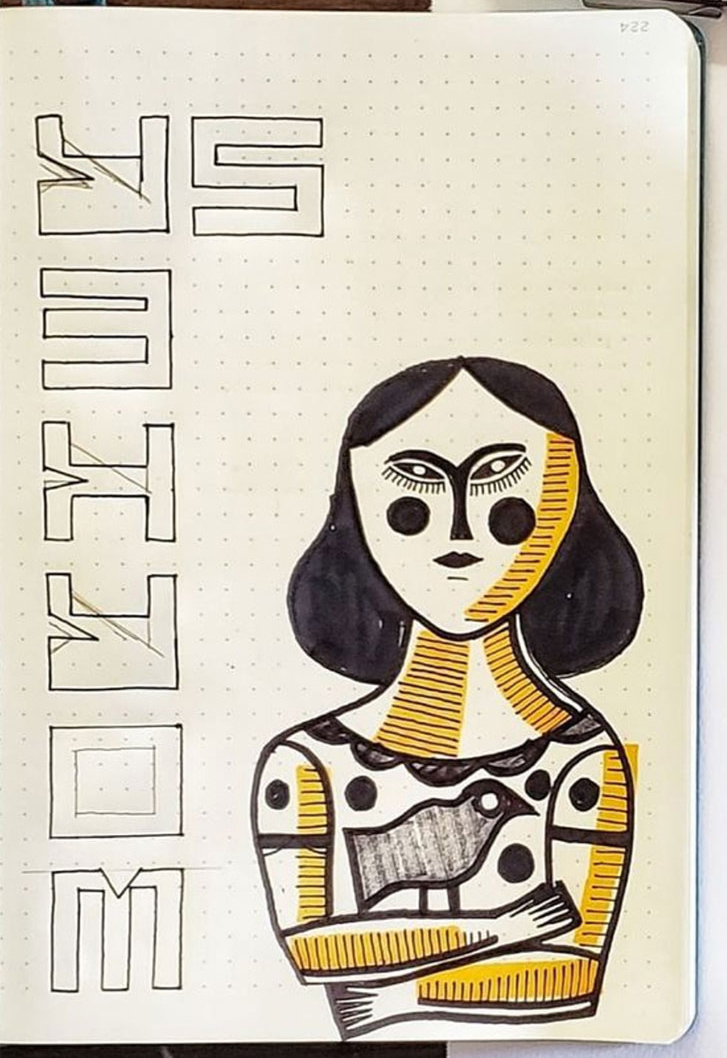

This is the fifth edition of Dispatches, an ongoing short interview series with political artists working around the world. We are excited this time to feature Ysidro Pergamino a printmaker from California’s Central Valley whose bold line work and sharp angles explore anarchist themes while also bringing in fantastical and decorative elements.

Will you tell us a little about yourself? Who are you? Where do you live?

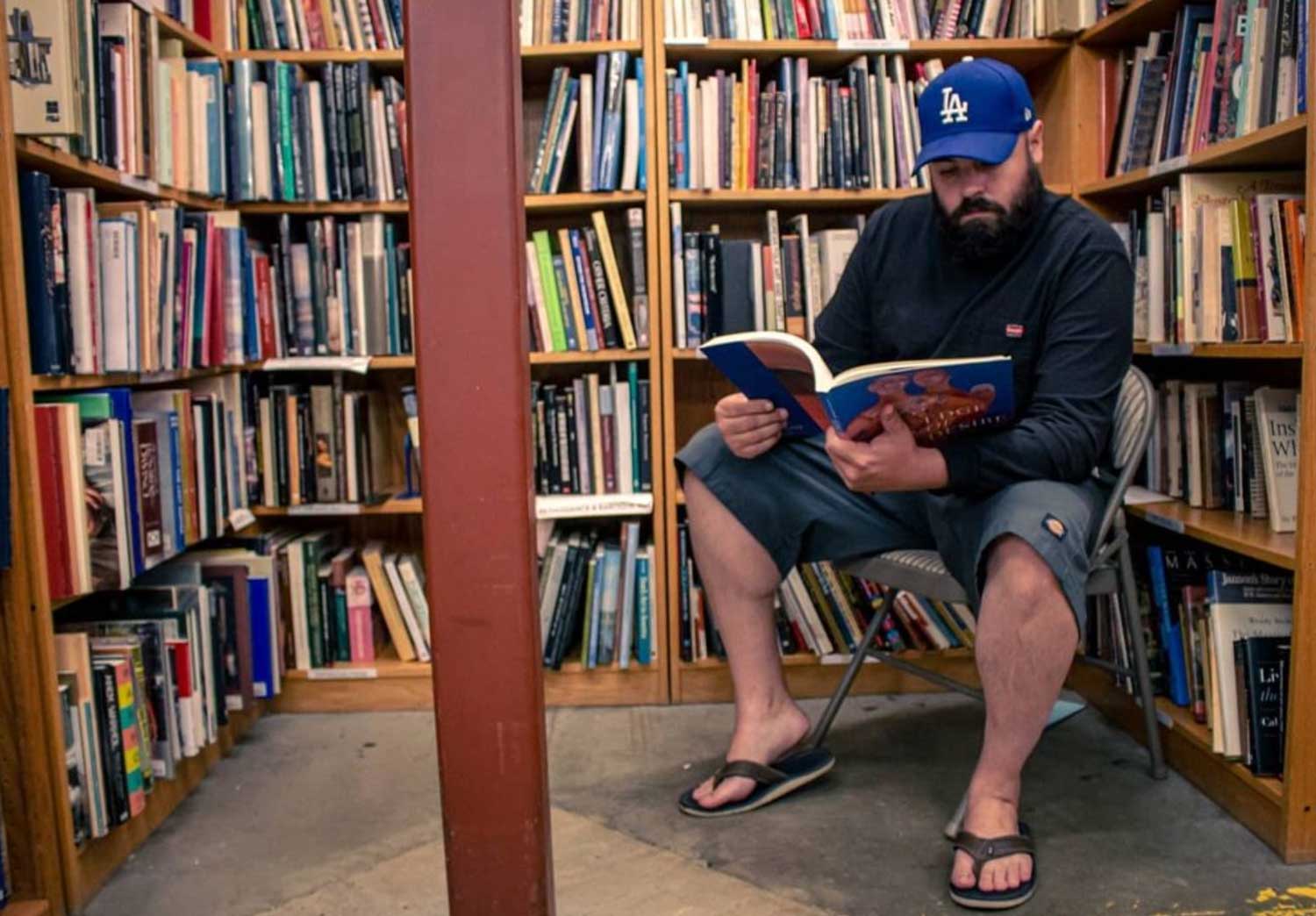

My name is Ysidro Pergamino. I’m a full-time intermodal truck driver. Before that, I worked all kinds of odd and unskilled labor jobs ranging from being a car detailer to installing fire safety systems in commercial buildings. I’m also a father of three amazing girls, and a self-taught printmaker, who clutters the kitchen table with art supplies and sketchbooks. I print with whatever extra time I have left; time is a scarce resource for me.

My parents are from Argentina. They migrated to the US in the early ’80s while the Guerra Sucia was in full swing. I was their first child. The reason I bring this up is because this experience has undoubtedly colored my perception of the world. I was born and raised in the states, but Argentina loomed largely in the backdrop. It was, in many ways, a culturally insulating experience: a silent walk between two world views. My parents weren’t at all concerned with the idea of assimilating into the fabric of American culture. When I was growing up, I never heard my parents speak English unless they were talking to my teachers or a telemarketer. Fortunately for me, our family moved to the sun-saturated central valley of California which has a rich Latin American community. It made growing up easier in many ways, and I’m happily still living less than 50 miles from the house my parents raised me.

It’s my day-to-day life that, ultimately, has a heavy influence on my work as a printmaker.

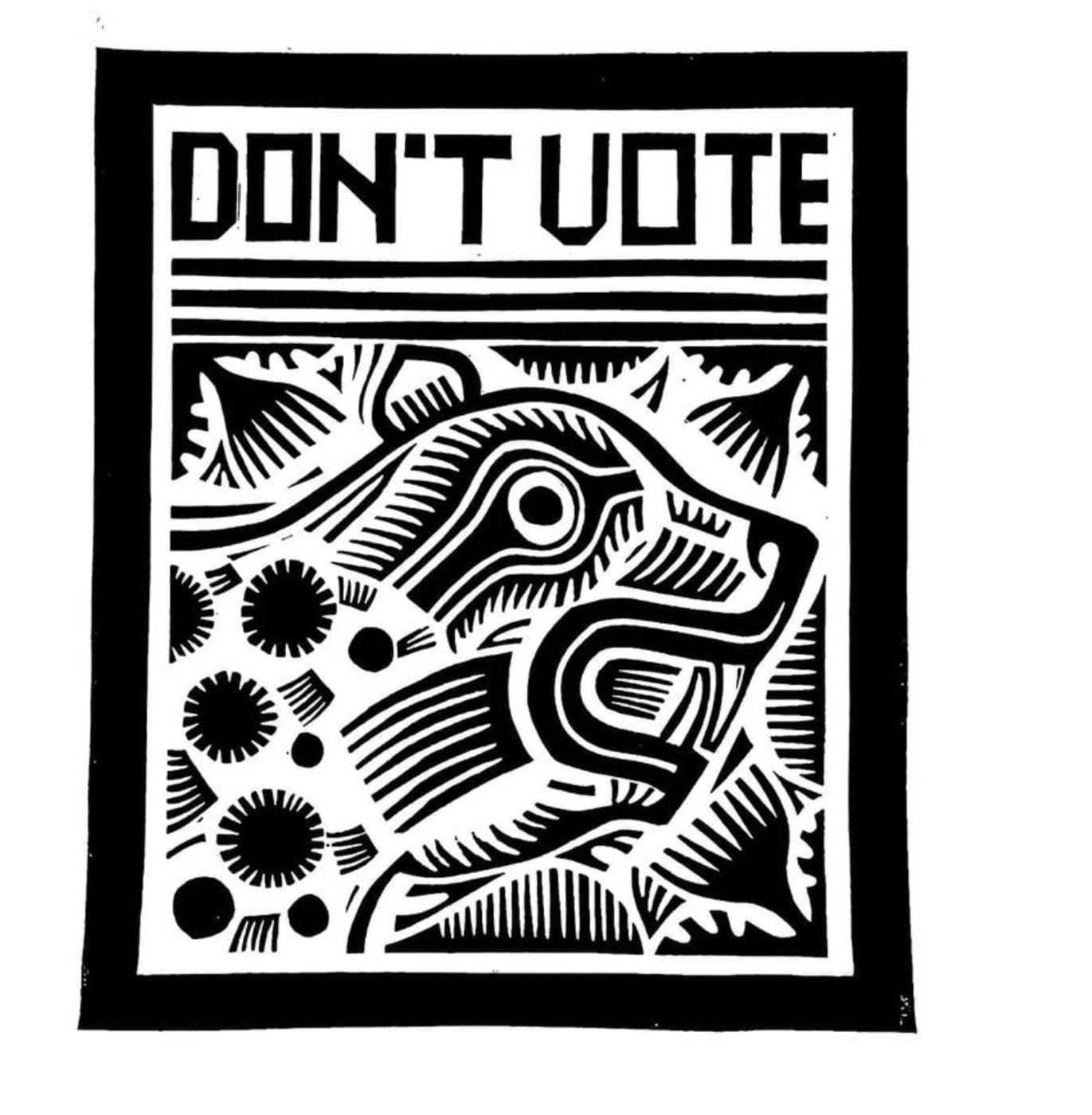

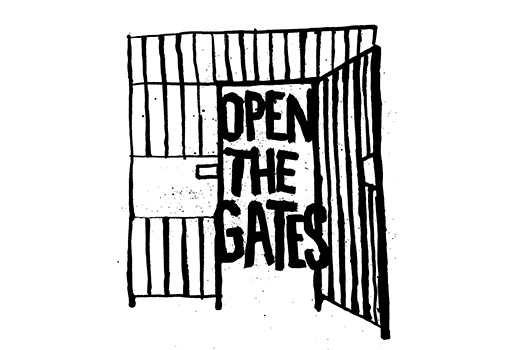

You’d mentioned that you are working through representing anarchist ideas without relying on the same tired old graphic tropes. What are some of the stereotypical images you are trying to avoid? Why is it important to create a different approach to these ideas?

Let me say right off the bat, I’m less than 3 months shy of celebrating my 40th birthday. I dived into anarchist thought in my mid-thirties. One of the reasons I think it took me so long to discover anarchism as a viable possibility is because I found the ‘closed fist’ trope pubescent. Don’t get me wrong- I’m not above violence.

How could I be? The neoliberalism of Margaret Thacher and Ronald Reagan was a neatly packaged procession of cannibalistic carnage. What do I mean by this? Well, if we are a byproduct of our surroundings, as some argue, it isn’t unreasonable to say our modern life engenders violence, or as the old Christian adage put it, “Violence begat violence”. The majority of my prints often portray violence. However, it took a while for me to see past the anarchist tropes, and I’m saying this because I think we need to be self-critical if our objective is to see anarchism thrive. I think it is safe to say that if Shepard Fairey, a good lapdog for the DNC, has successfully co-opted leftist motifs, then those motifs have run their course.

However, the cup is not half empty, there is some fantastic work being produced right now.

I like Rosanna Morris (@rosannaprints), Landon Sheely’s ‘You Are Still Alive’ series (@landonsheely), and the work that my friend Addy Rivera Sonda (@addy_rivera) is doing. They’ve been able to drop the tropes and they’re doing it well, and that excites me! They’ve indirectly given me, a person who has just recently picked up printmaking, a path forward.

I love all your big bold lines and shading and your sharp angles everywhere your work is very printerly. Could you talk about why you’re drawn to making images like this?

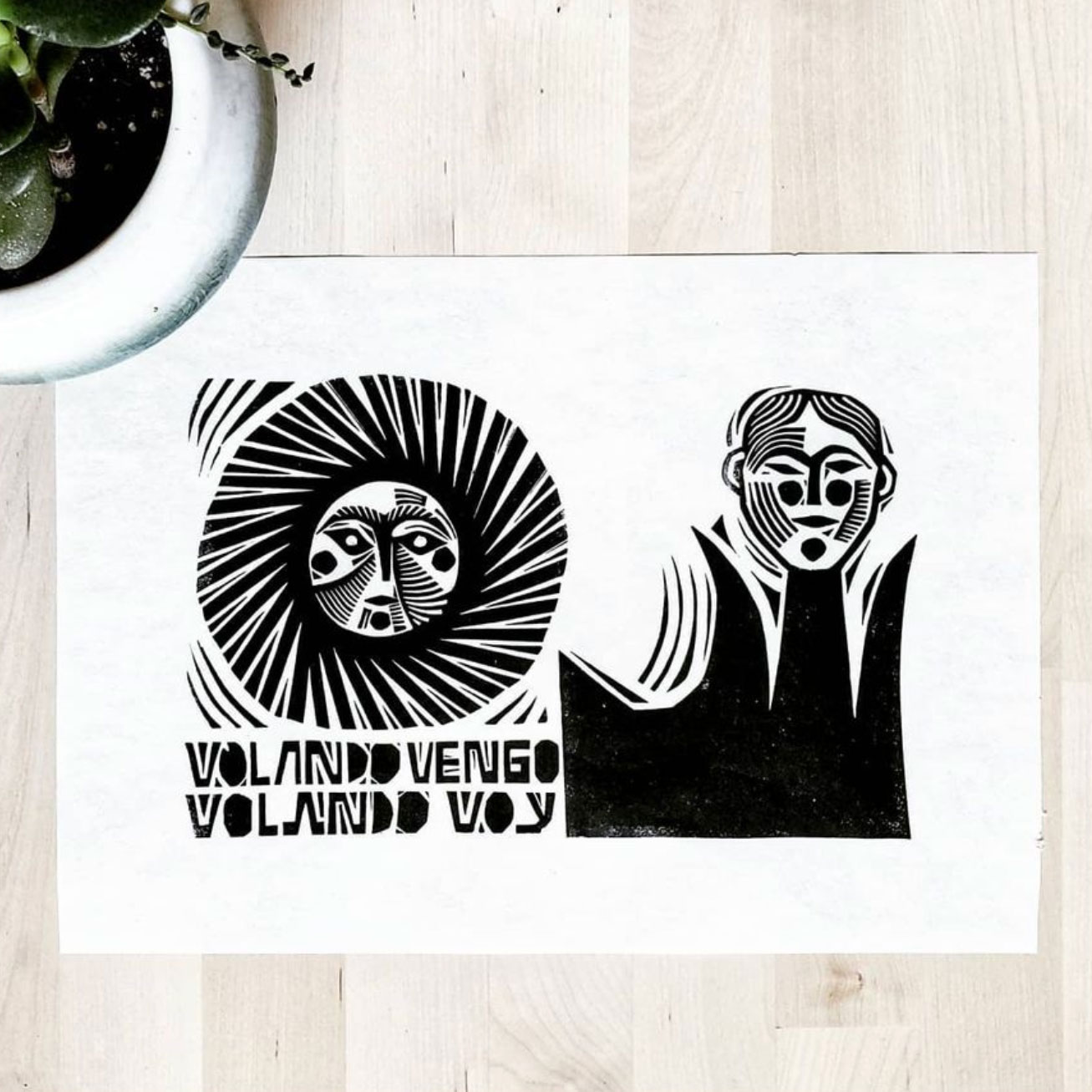

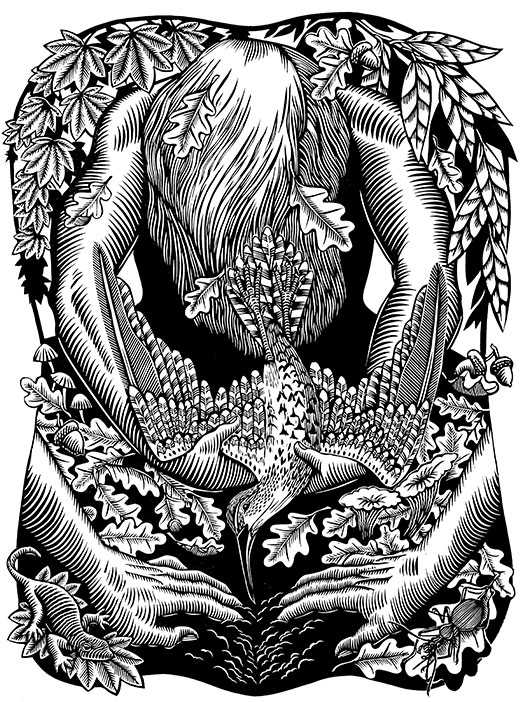

As I mentioned before, I’m a self-taught printmaker. I’ve had no formal education in the arts. In some ways, this lack of training has hindered me as a creative. That’s the truth. But, on the other hand, I like to think my visual voice to some degree has remained uncontaminated by the trends taught in art school. You know, the shit professors deem as ‘good’ art. I had very little unlearning to do, in that sense. So, for two decades I was able to, at my leisure, meander around looking at whatever resonated with me visually and my prints are the product of this approach. Nothing was off-limits. I had no one telling me what to like, so I was able to enjoy comics, arté popular, folk art, traditional Americana tattoos, pre-Columbian textile, matchbook advertising, and graffiti. The Fileteado Porteño, painted from end to end on buses, with its vibrant colors that cut through the winter grey of Buenos Aries has left an indelible imprison on my childhood memories. I was also intrigued by avant-garde art movements such is as Boris Lurie’s ‘No!Art’, COBRA, DADA, and Fauvism just to name a few. I ran free. I was able to implement in my sketchbooks what Herbert Read wrote in his easy, To Hell with Culture, “We should not be pleased with the way certain things look unless our physical organs and the sense which controls them were so constituted as to be pleased with certain definition proportions, relations, rhythms, harmonies, and so on.”

I try my best to keep my work as simple and unrealistic as possible. I prioritize the movement and feelings my linework can or doesn’t invoke in any given print.

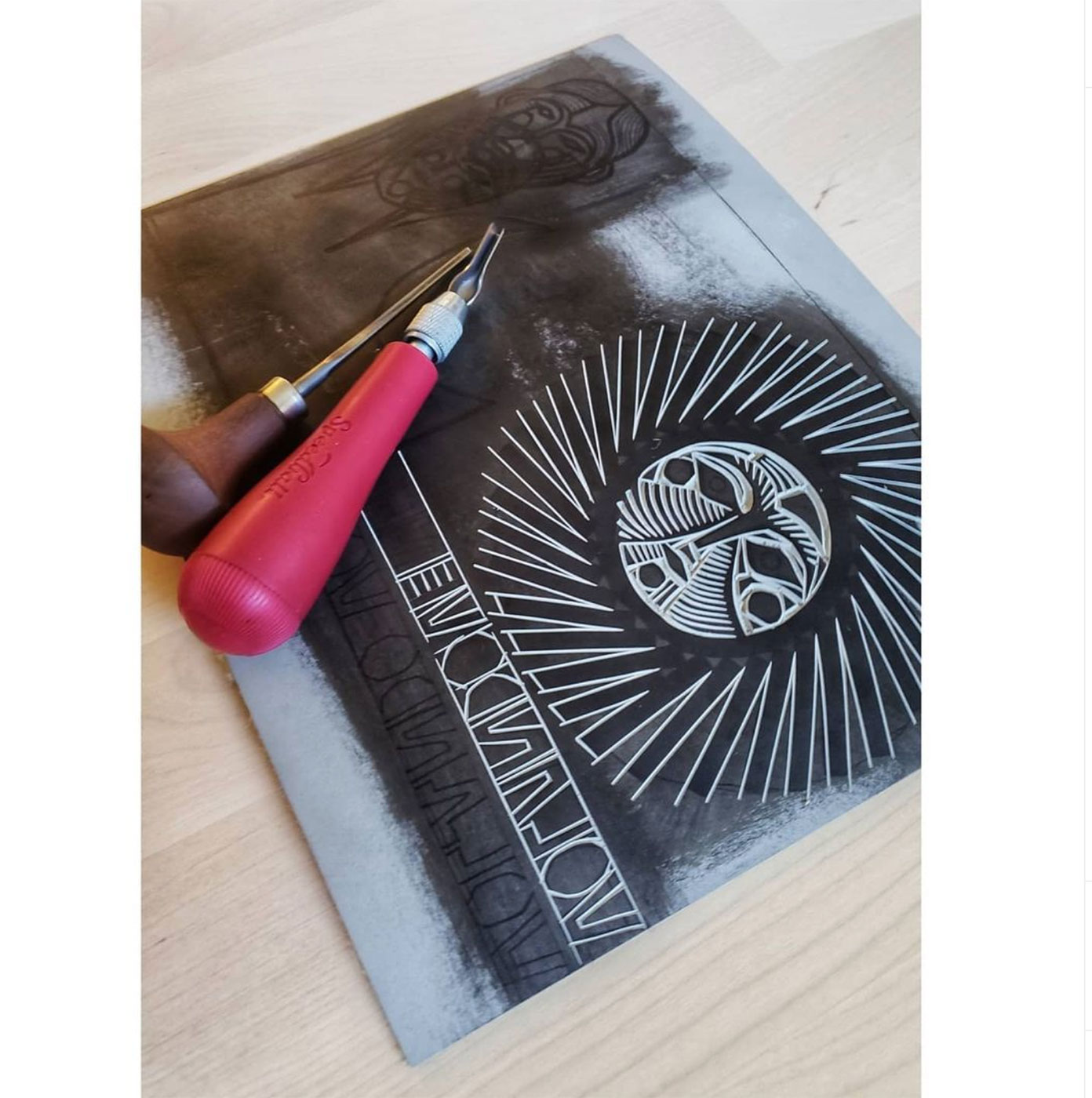

Working in a medium that is reduced to just 2 colors, black-and-white, makes it critical to have a clear idea of what you want to say and cut out the rest of the bullshit. There is no room for it in print. Thick bold lines demand attention. I’ve found them to be profoundly useful.

Look at printmakers like Antonio Berni, Antonio Frasconi, Barbara Hanrahan, Tamayo, Leopoldo Mendez, José Guadalupe Posada, Augusta Savage, Shikō Munchata, Kōshiro Orichi, Un’ichi Hiratesuka, Suamico, John Muafangejo, Rita Corbin, the woodcut prints of North Eastern Brazils corded tradition. What do all these masters and traditions have in common? Powerful line work. So, I’m trying my best to build on that foundation. I go about making my prints intuitively. They have to feel right. They have to visually make sense to me. Those are the criteria I use as a craftsman.

Can we walk through one or two images- for example, the CNT/FAI graphic and the ‘Los Chorros de Wall Street’ print. What were these made for what was the intention? How did you choose the images/subjects? What is your process like?

Believe it or not, I usually don’t get too many questions directly concerning the meaning of my prints. I’m not used to having to explain my works to anyone. While thinking about your question, I’ve come to realize, surprisingly, how muddled my brain is. I don’t have a set methodology when it comes to my work. My prints come about organically. I don’t want to overthink them like I do everything else in my life. They help me get over my neuroticism.

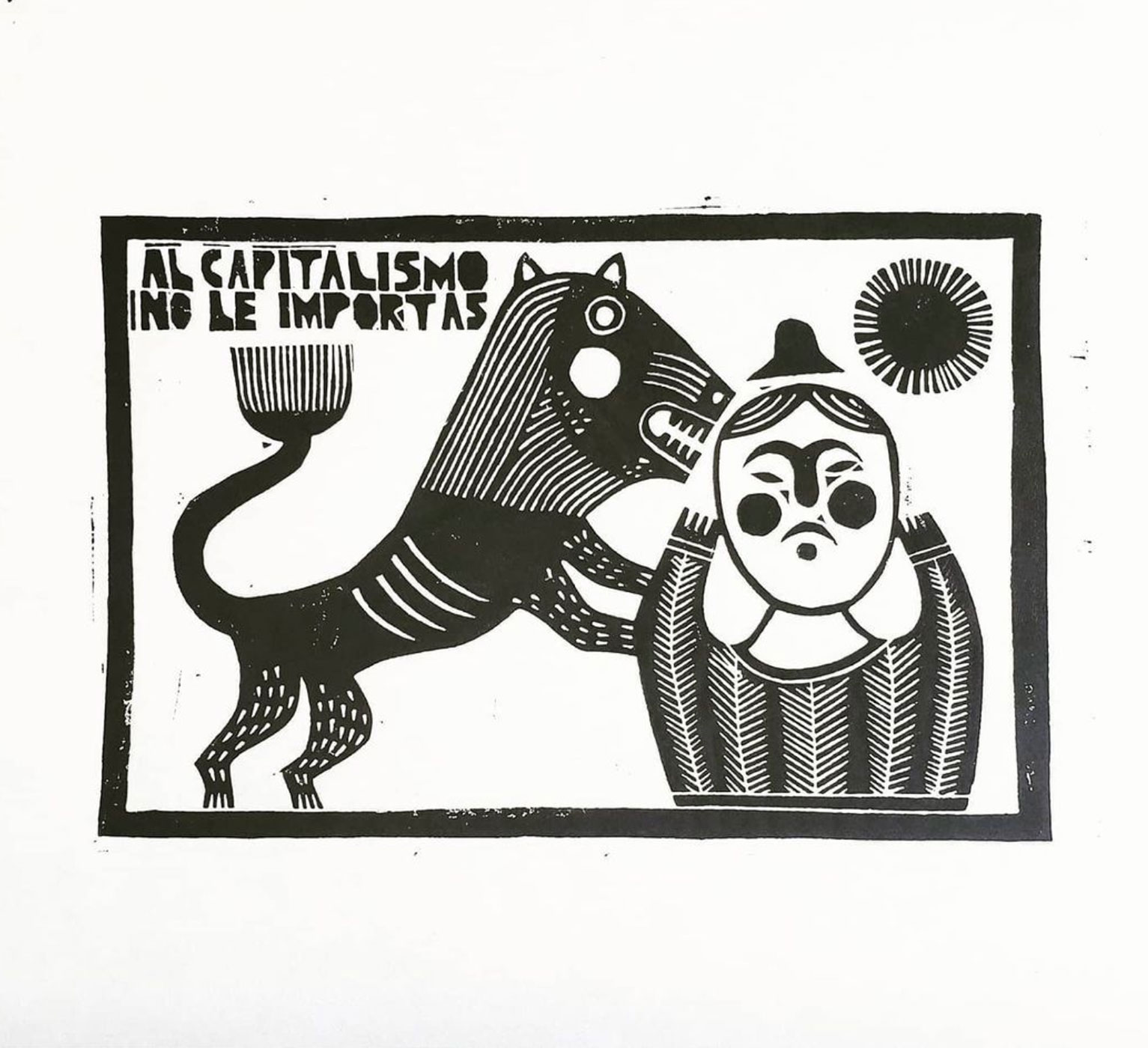

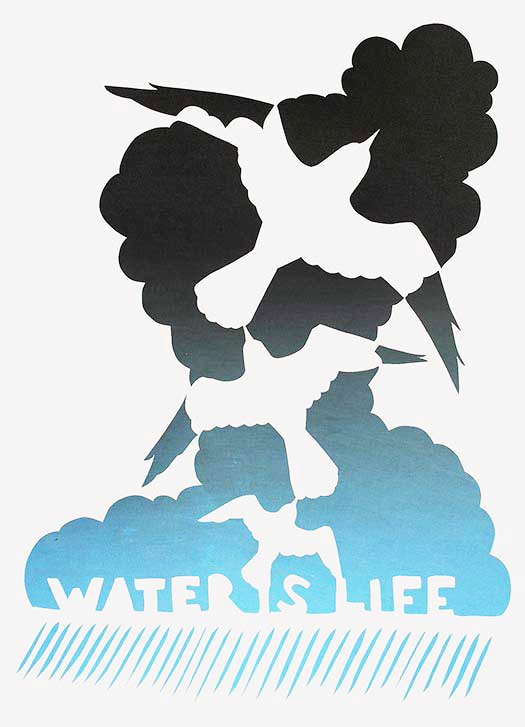

In the print, for instance, ‘Los Chorros de Wall Street’, several elements are at play, and somehow, unintentionally, come together.

What helped spark the making of this print was an article I read by Chris Hedges, ‘The Age of Social Murder’. In this article, he lays out the same argument Friedrich Engels did in his book, The Condition of the Working-Class in England published in 1845. Both Hedges and Engels agree that the ruling elites are murderers. I’m not gonna go into the details of why they say the elites are murderers because if anyone is interested they can go directly to the source, i.e. the article or the book.

That was the springboard.

The reason I choose to use the word chorro for the people working on Wall Street is that the word ‘chorro’ in Argentine slang means petty criminal, but it also has the same social and racial connotations as the word thug does here in the States. I was being a little tongue in cheek while trying to open up a dialogue, like Hedges, about the criminals we should be concerned about. After all, I don’t think a small-time drug dealer setting on some neighborhood corner has impoverished the community the same way Jeff Bezos has. Right? Yet, no one says this seriously on CNN or the New York Times. In fact, Bezos is celebrated. It’s an upside-down world we live in, and no matter how much we believe in reason, science, or technology, it won’t fix our backwardness.

The third part of the print was inspired by the Yaqui, Huastica, and Mayan cultural symbols of the deer. For these indigenous groups of Mexico, before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors, the deer motif represented the vivacity and dynamism that animates life. I choose to use the deer for this reason, and, of course, the ravenous wolves represent the antonym of life—death.

This is my way of extracting Hedges’s concept of Social Murder from the abstract and putting it into a visual context.

As for the untitled print of the man riding a horse with the letter CNT and FAI to the side of him, it is far less convoluted and much more straightforward.

I’m currently reading my third book concerning the Spanish Civil War of 1936 to 1939. This singular moment in Spanish history has occupied my imagination.

The print is a simple homage of the people, people like you and I, bus drivers, factory workers, teachers, cooks, and so on, who took up arms against their exploiters. They understood the fluidity of revolution and organized it appropriately. They created a functioning society in the middle of the statehood wastelands of Europe. I don’t want to romanticize the war, but it’s almost impossible not to do. So, I couldn’t think of a better motif to confiscate than the Catholic iconograph of Saint George which is meant to depict the triumph of the virtuous over the wicked. You’ve got to have a sense of humor in life, even if it is a bit morose.

Are you working on any projects right now that you are excited about and want to share?

I don’t function on that level. My brain doesn’t work that way. For better or worst I’m operating on a different wavelength. I don’t see my prints or myself in those terms. I’m not a professional artist, I guess. Honestly, I find professionalism repulsive. It killed local and work-oriented journalism, radical unionism, and has rendered art–castrated. It is a part of the vanilla envelope colored technocratic dictatorship Kafka warned us about. Hahaha. So, the short answer to your question is no. I’m just doing my thing. I’m more closely related to the folk artists, artisans, and craftsmen I’ve come across in both North and Southern Latin America. Fuck the business card mentality.

Who are some artists (living or dead) that have inspired you, that everyone should know about?

As for printmakers or propagandist works I like, well, you can’t go wrong with John Fleissner’s (@johnfleissner) prints, and from across the pond I like what @blacklodgepress is doing. I also enjoy what @fabricadeestampas, they just published a book in Spanish, La Anarquía Explicada a los Niños which I highly recommend.

Anything else you want to add?

I think I’ve said enough, no?

Where can people find your work?

For those who don’t live in the central valley, you can check my stuff on Instagram @https://www.instagram.com/ave_cosmica_prints/

Signal: A Journal of International Political Graphics & Culture is the collective project of Josh MacPhee and Alec Dunn. All copies of Signal are available for sale here on Justseeds.

Interview conducted via email in January, 2022.

Ysidro Pergamino’s instagram is no longer active. I wonder if he had too many requests? I am one of them, a high school art teacher in East Los Angeles. I would love to purchase a Corozon Rebelde print to hang in my classroom if they are for sale.

Looks like he’s relocated to here: https://www.instagram.com/ave_cosmica_prints/