A review of “Remaking the Exceptional” at the DePaul Art Museum by Brian Holmes

Chicago is notorious for police violence against people of color – including arbitrary executions on the street and confessions exacted under torture. For decades, inhabitants from across the city have pushed back, winning a substantial, first-of-its-kind municipal reparations law for torture survivors in 2015 and continuing since then to advance cultural, educational and legislative projects that aim to redefine power and its legitimacy at the local level. Large and diverse groups of artists have played an active role in these movements for justice, alongside family members of the victims, grassroots advocacy groups, journalists and lawyers. The exhibition “Remaking the Exceptional: Tea, Torture, & Reparations,” on view at the DePaul Art Museum March 10 through August 7, 2022, bears witness to these engagements. The show includes core contributions from Chicago Torture Justice Memorials and the Prison+Neighborhood Arts/Education Project, as well as many associated local artists, all collaborating with their communities. Such a movement periodically needs to express what it’s all about, and to listen again. At the opening, the testimony of three survivors made the moment, reawakening emotions and renewing long-held commitments.

Carl Williams speaking at a Chicago Torture Justice Memorials and Prison+Neighborhood Arts/Education Project gathering at Remaking the Exceptional, 2022.

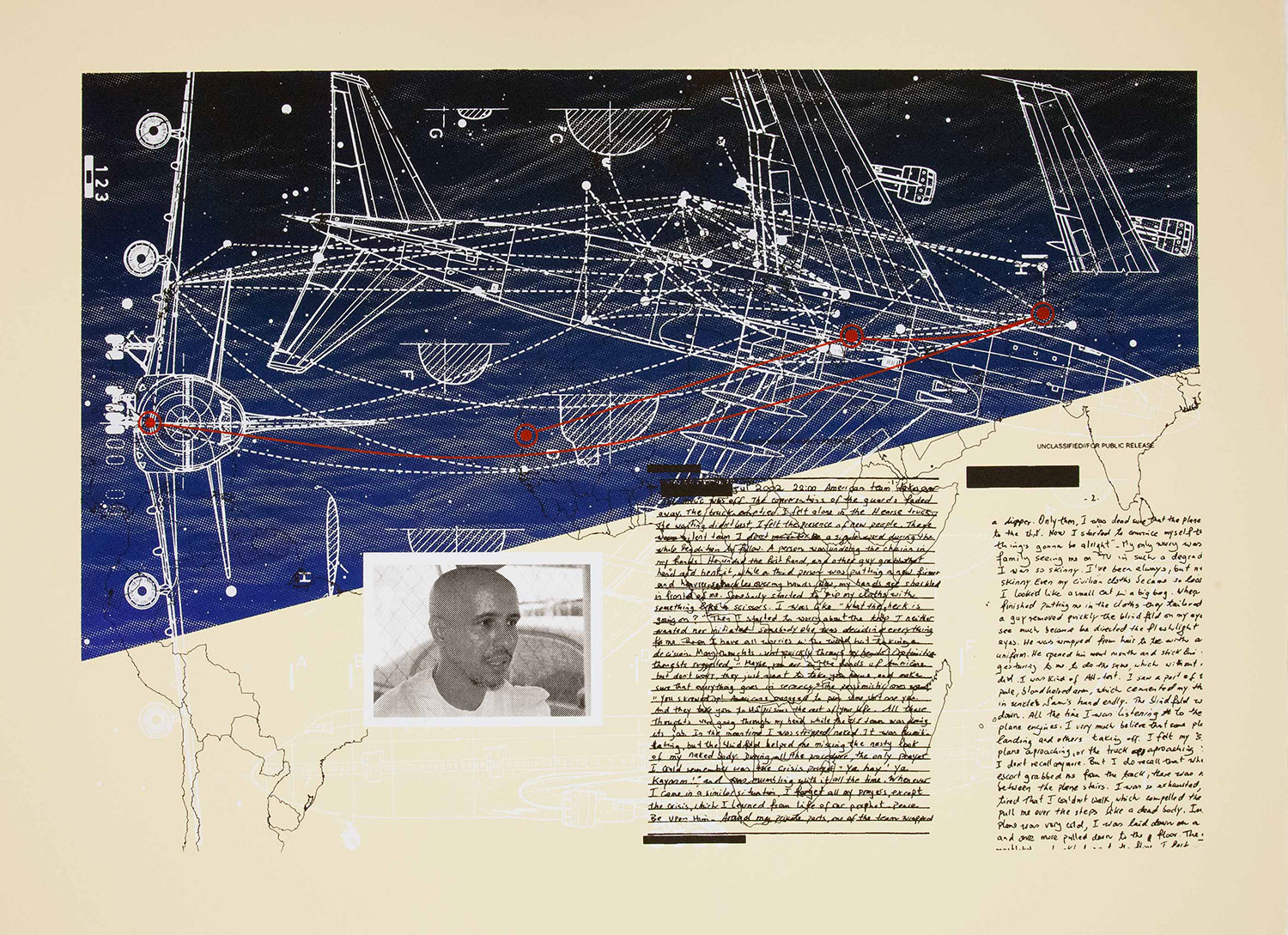

Amber Ginsburg and Aaron Hughes are the artist-curators of “Remaking the Exceptional.” What they have done, within the wider constellation of the torture justice and prison abolition movements, is to follow a direct line from the Chicago PD to Guantánamo Bay, in order to start a conversation about injustice and incarceration on a scale that is both global and disturbingly local. The direct line was drawn by the career of Richard Zuley, a Chicago detective remembered for his uncanny ability to wring out a confession. Zuley also happened to work occasional contracts for the Navy, and he mobilized in 2002 when the “Global War on Terror” began. He is known to have carried out particularly ignominious acts of torture on the person of Mohamedou Ould Slahi, who survived to tell the story in his Guantánamo Diary. Only because of a single slip by the military censor who redacted the document would anyone on the outside learn the identity of Slahi’s torturer.

Left: Tea Project (Amber Ginsburg and Aaron Hughes), Extraordinary Rendition of Mohamedou Ould Slahi, 2022

Right: Tea Project (Amber Ginsburg and Aaron Hughes), People Rise Like the Water, 2022

That’s exceptionally important knowledge: but the heart of the conversation is elsewhere. What Amber and Aaron have brought to visibility, on the 20th anniversary of Guantánamo’s reopening as an “enhanced interrogation center,” are a large number of artistic expressions made by the imprisoned: paintings and drawings that only escaped the offshore military base through attorney-client privilege. That escape hatch was shut by the Trump administration and has remained closed under Biden, in a display of repressive paranoia that proves the political relevance and radicality of what are often simple depictions of flowers. Alongside these evocative works, the visitor encounters delicate ceramic reproductions of styrofoam tea cups that the men would habitually decorate with inscribed lines, tracing abstract patterns and flower motifs into the soft material, usually with just their fingernails. The human warmth of a shared cup of tea and the spiritual release of painting and drawing define the horizons of this project, which also includes pictorial works and sculptural forms by the two artists, as well as fascinating podcasts in which torture survivors mingle their reflections on what it takes to live through situations that most of us can barely imagine. Ultimately the Tea Project seeks to reach out to all the Guantánamo survivors, not forgetting those who still languish in captivity, in order to offer a ritual ceramic cup and engage further conversations toward the goal of ending domination, war and torture, wherever they may occur.

Liberation

The exhibition opens with a “Wall of Names,” roughly two hundred of them, representing all those who are known to have undergone torture at the hands of the Chicago police detective and Vietnam war veteran Jon Burge, from 1971 to 1991. Survivors are invited to sign their own names on this wall, marking their liberation – or at least, the first steps toward it, because as one of them insisted during the opening event, the after-effects of decades in prison do not simply vanish when a key is turned in a door. Directly opposite the wall are five large-format photographs by artist Debi Cornwall, each portraying a Guantánamo survivor from behind as they look out on the civilian world (not always their country of origin) to which they have been summarily released without recompense for long and unjustified confinement, and without any form of assistance in putting together the pieces of shattered lives. A quote on the wall from Mansoor Adayfih reads “Guantánamo is not exceptional. Injustice can be anywhere, in the family, in the country, as a system, or even within individuals.”

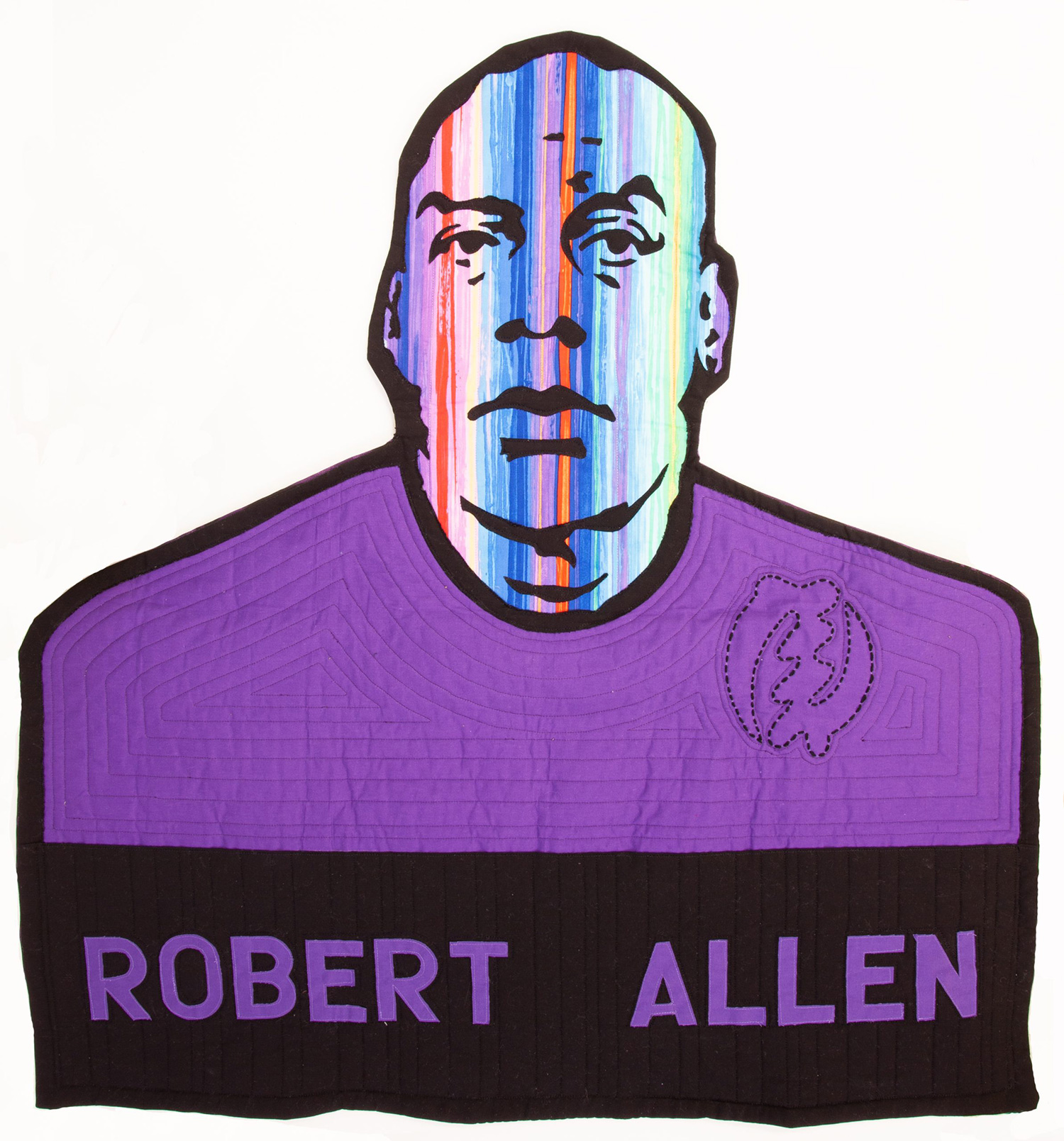

Dorothy Burge, Free Robert Allen from the series Won’t You Help to Sing These Songs of Freedom, 2021. Quilted fabric.

Above the exhibits, hanging in the air like glowing guardians, are quilted portraits by artist and community activist Dorothy Burge (no relation to the aforementioned cop). Dorothy is a “quiltivist” who carries on a long-held family tradition, now imbued with contemporary concerns. Her brightly colored portraits bear the names of torture survivors who are still in prison and, on the upper floor, of youthful relatives who have stepped up to join the Black Lives Matter movement. Throughout the exhibition they exhale the spirit of a new political generation, full of energy and courage, but without a drop of naivete concerning the world with which they must grapple.

Open Seas

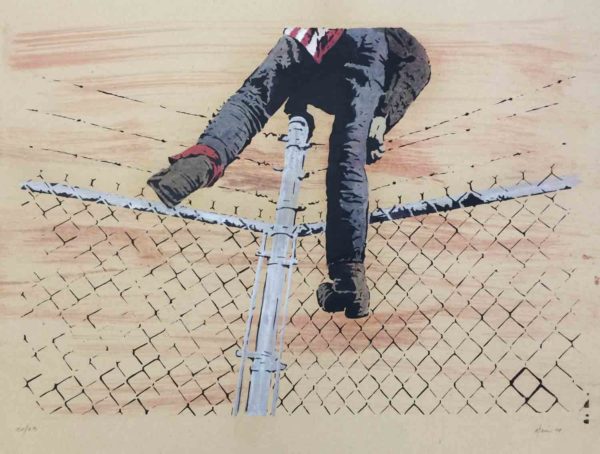

Move on to the adjoining gallery, where a plethora of detail captures the eye. Here are hundreds of ceramic cups on narrow shelves, surmounted by dozens of flower paintings born in Caribbean captivity. But there is more: a wheeled wooden cart with kettle, tea and spices at the ready, and behind it, an incongruous wooden dock that seems to float in some uncertain historical space. Both the dock and the tea cart are marked with orange paint at the base, up to what would seem to be a waterline. A low speaker looking like an air vent emits a sound of lapping waves, while a vertical “ear horn” of the kind that used to feature on a gramophone plays the podcast interviews with survivors. Wooden stanchions support silkscreened collages alluding to war technologies and military deployments, in a visual language that evokes old-fashioned circuit diagrams. On one of them, a conventional map of the US is bisected by a dark diagram of flight plans, connected by sinuous white lines to the names of individuals who alternately served as policemen or prison guards in the US, and as service members in America’s brutal overseas wars.

Tea Project (Amber Ginsburg and Aaron Hughes), Ode to the Sea [installation], 2022.

Behind all of this rises a tapering upright box like the housing of a grandfather clock, decorated with what seem to be burnt inscriptions, pierced at the base by a polished tree trunk and topped by an old bakelite telephone handset, whose dangling cord disappears into a small circular hole. Inevitably you make your way toward this object, pausing just as inevitably to gaze at the painted flowers and incised tea cups. When you reach the other side of the tapering monolith, you see that it contains an army field telephone on a shelf, complete with circuit diagram. A dark tea cup on a higher shelf bears the effigy of a machine gun. The tree trunk, visible within the lower part of the housing, has become the generator coil of this army field telephone – which, as you will learn in the exhibition or perhaps already know, can be used as a banal torture device, delivering a wavering, hand-cranked shock, whether in a local Chicago precinct office or on a distant naval base. Exiting from the wooden phone booth, the horizontal tree trunk splits into many branches, each of them pierced by rusty iron nails. The memory of ancient trade routes and colonial expropriations seems to wash around the whole wooden dock, evoking the vast space of historical encounters between civilizations, whether warm and welcoming, or violent and traumatic.

For sure, anyone who has read Guantánamo Diary will also recall the day when Richard Zuley sent a blindfolded Mohamedou Ould Slahi on a long sea voyage, putatively to a new and threatening location, in a perverse psychological effort to “soften him up” with fear and disorientation before yet another interrogation session. Anyone familiar with the history of counter-insurgency will recognize the sinister role of the field telephone in Algeria, Vietnam, Argentina and many other conflict zones. As for the polished branches pierced by rusty nails, they speak of the “torture tree” described by anthropologist Laurence Ralph, whose work has been another fundamental influence on this show. As Ralph has observed, the abuse that continues to happen in Chicago is no mere “boil” or minor disfigurement that can easily be wiped away. Instead it is “deeply rooted in the culture of the Chicago police force.” As he continues: “Police torture is a tree—a hideous and disfigured tree, a tree that blooms death rather than life, a tree that casts a long and dark shadow.”

Look upward from the torture tree to three brightly painted seascapes, each of them depicting sailing ships from another era, tossed on tumultuous waves. One of the painters, Djamel Ameziane, is quoted on the title card: “I overcame the conditions of imprisonment all these past years by always maintaining hope that one day I would be freed, because I am innocent… The past years were all the worst moments. I would describe them as a boat out at sea, battered by successive storms during its trip towards an unknown destination, benefiting only from very short periods of respite between two storms. These respites were the best moments.“

Ghaleb Al-Bihani, Untitled, 2015.

Futures

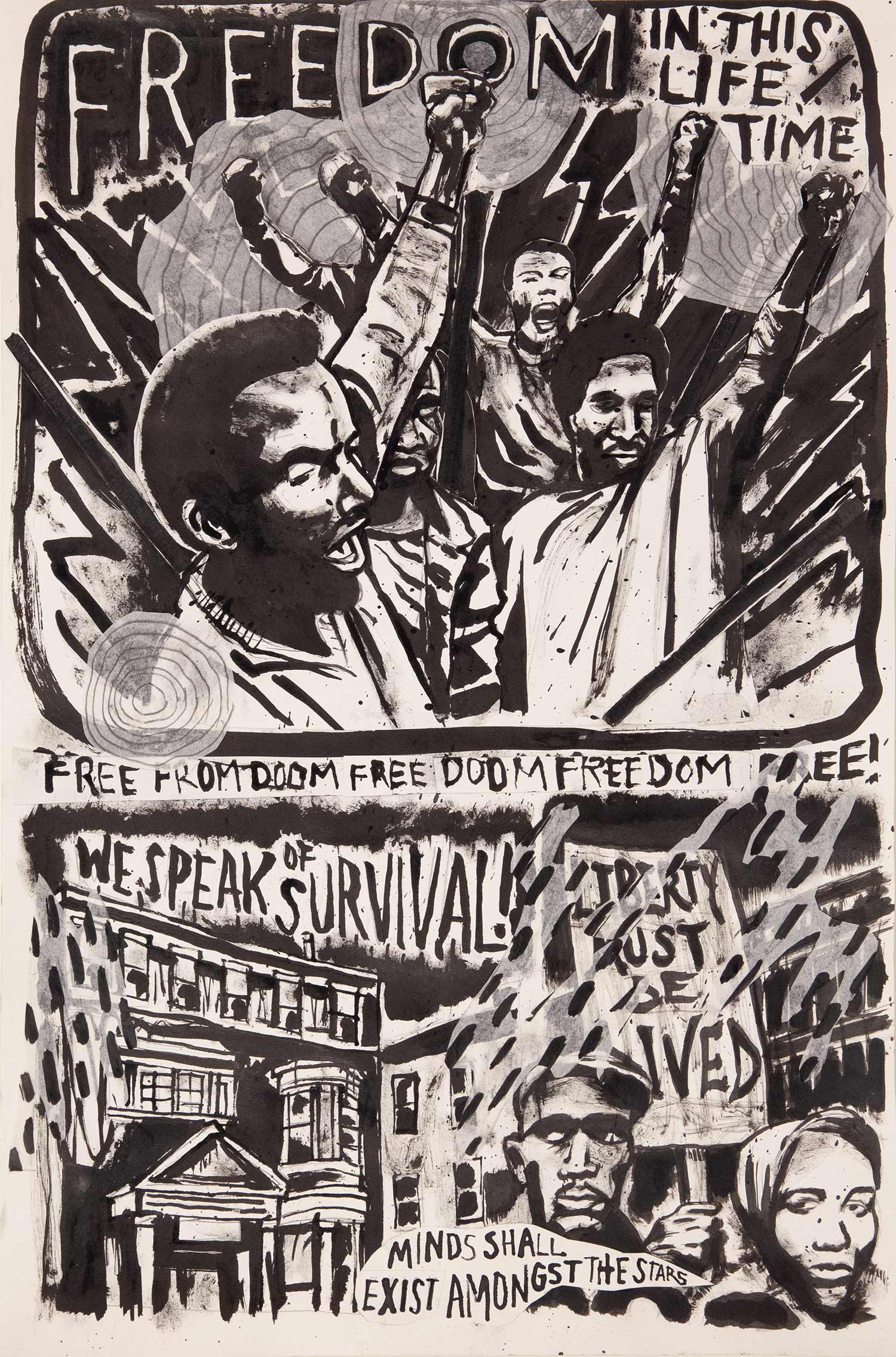

The show continues on the ground floor of the De Paul museum with an electronic storymap detailing the links between local and global scales of officially sanctioned violence, prepared by the Invisible Institute, whose research on police abuse in Chicago has been foundational. After absorbing many pieces of that deadly puzzle, one takes the stairs to the upper level, where an outpouring of works by local artists and communities envisions futures beyond mass incarceration. “This is our list of demands,” writes artist Damon Locks on a handmade print: “Beauty, Form, Destiny, Love, Time, Future and Light.” On the opposite wall, photographer Sarah-Ji Rhee documents recent abolitionist protests in Chicago after the murder of George Floyd. Her work reveals vast and remarkable collective actions: living testimonies to popular resolve in the present. Nestled into the corner of this gallery are a large number of pieces created in classes organized by the Prison+Neighborhood Arts/Education Project at Stateville Prison. These works depict the emblems, customs and watchwords of an imaginary 51st (Free) State, populated by millions of currently imprisoned people. The makers of the works, though still inside, have already taken their first steps toward liberation by reenvisioning the existing carceral society.

Damon Locks, Keep Your Mind Free, 2021.

The final room contains photographs of Bagram Air Force Base in Afghanistan, produced by artist Trevor Paglen, which serve as bookends to a series of drawings where both Chicago and Guantánamo torture survivors depict the outrages to which they were subjected. On a cloth banner hanging from the wall is the text of the reparations ordinance from 2015 – originally drafted by movement lawyer Joey Mogul as a speculative monument, and now enacted as municipal law. It faces the text of a similar, not-yet-enacted law of “Reparations for Guantánamo Torture Survivors,” which gestures forward to justice on a far larger scale. Yet this is not really the end of the show. Instead you exit through a corridor-like space with an entire wall taken up by an annotated and modified reproduction of House Resolution 194, “Apologizing for the enslavement and racial segregation of African-Americans.” On the other wall, left almost blank, a series of questions invite answers from the public: “Are white people healed from enslaving? If not, what is needed to heal?” “Are black people healed from being enslaved? If not, what is needed to heal?” “To you, what does accountability for enslavement and segregation look like?” and so forth.

Anyone doubting whether the ideas and demands of the prison abolition movement have made their mark on the wider Chicago public had only to return to that blank wall a month later. The entire thing is now covered with profound and detailed statements of the steps yet to be taken toward healing, accountability and liberation. The public has clearly spoken.

To close this brief review, I’d like to repeat what this show makes devastatingly obvious: the fact that torture and the abuse of power are anything but exceptional. It is not to these banal and all-too ordinary acts of violence that the title of the exhibition refers. What the show does instead, through the delicately inscribed tea cups and all the exhibited artworks and documents, and indeed, through the living gestures and speech of its many participants, is to restage the exceptional acts of resistance and visionary expressions of love that alone are capable of remaking a damaged world.

Brian Holmes is an essayist, artist, and activist working on political ecology.

For more information on the “Remaking the Exceptional: Tea, Torture, & Reparations,” exhibition at DePaul Art Museum visit: artmuseum.depaul.edu