While I’ve been working on the redesign and expansion of the exhibits at the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, I’ve been thinking a lot about how to bring coal, as a material, into the space. In doing so, I want to put the Mine Wars era into a global and geological context for visitors. We hadn’t done this previously, in the first iteration of our museum, and it feels important to ground our story in time.

Consider the formation of the rock we call coal, the violent tragedy of our search for and extraction of it, and our modern binge on burning the last of it. Imagine vast prehistoric wetlands, where coal is first formed from the sediment of dead plants and animals. Draw a line from forests of giant, sporulating trees to highways built on exhausted strip mines and waste slurry impoundment lakes which burst to drown whole human communities.

The coal-company-funded preachers that reigned in the privatized mining settlements early in the last century in Appalachia have a lineage in pockets of cultish fealty to contemporary murderers like Don Blankenship and insipid industrial propaganda organizations like Friends of Coal. Coal can become a religion.

This is the Fuel chapter in the foundational text of our modern culture of death, and it’s a fantastically bizarre tale. One through line is the continuous struggle for justice, dignity, and the health of the human communities which live within the global coalfields and are often employed in the mining of the underground seams of it. That’s where our museum comes onto the stage.

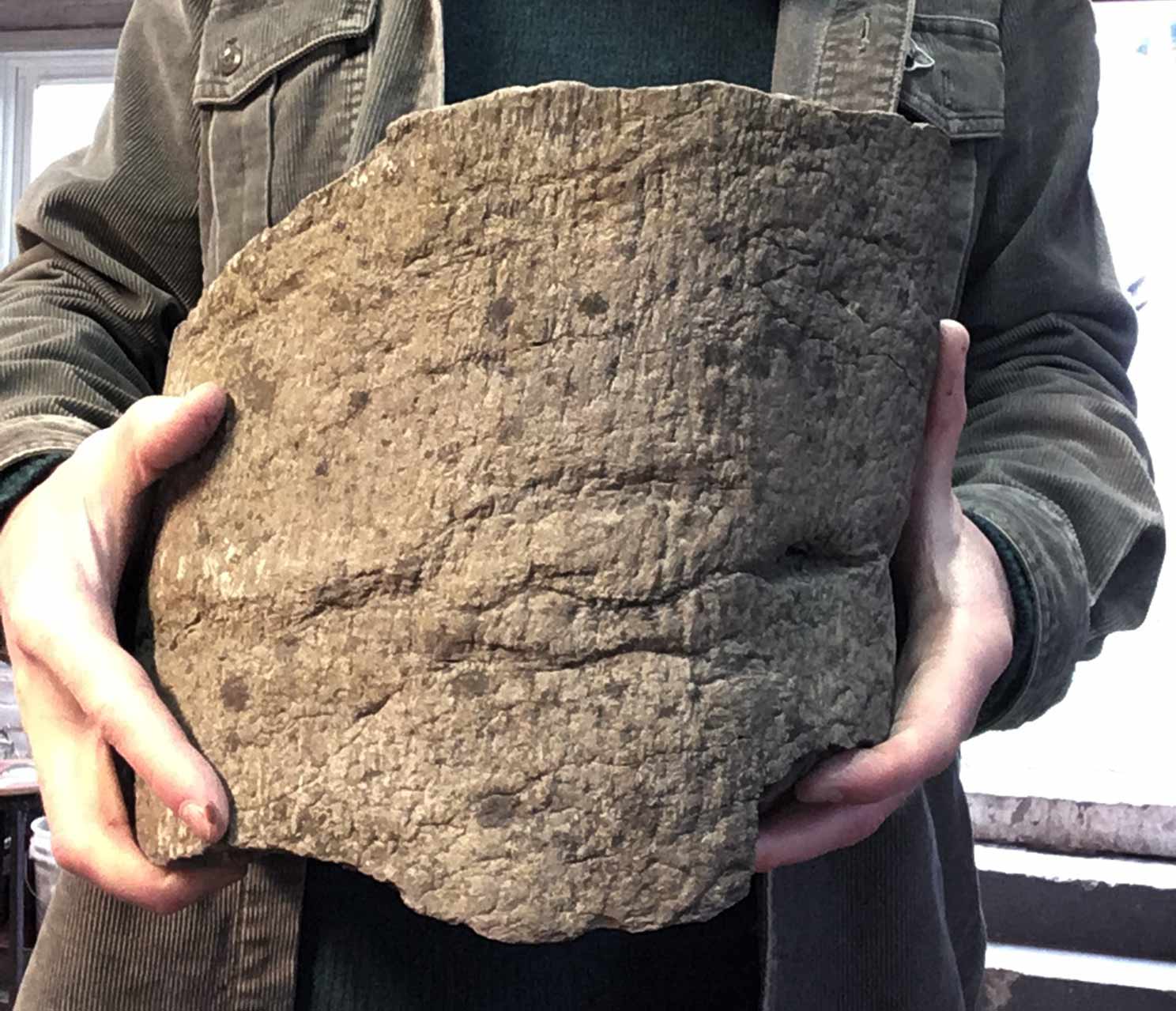

Here are a couple of paleontological artifacts that are new to the museum, and I’m excited to be working with them.

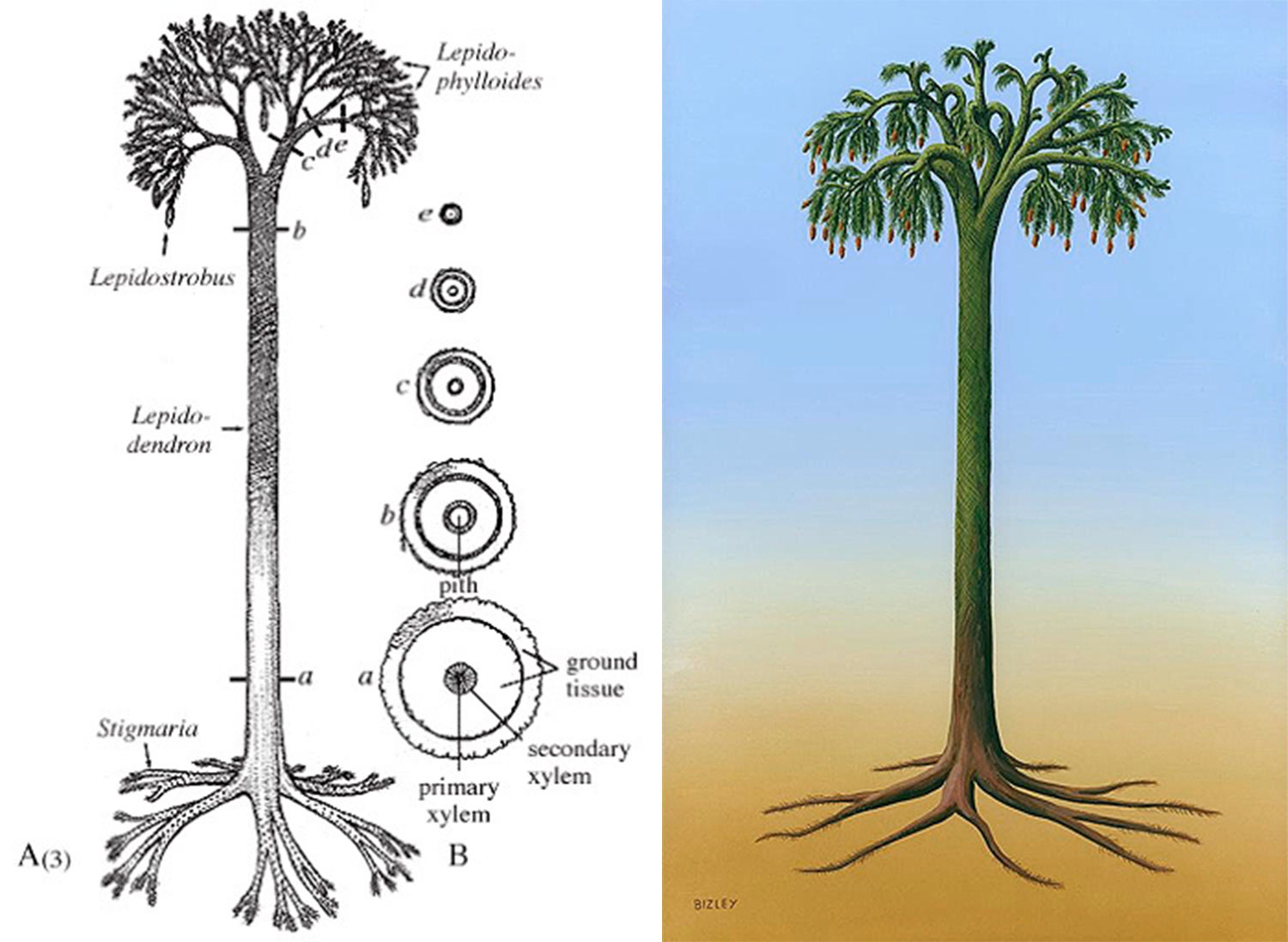

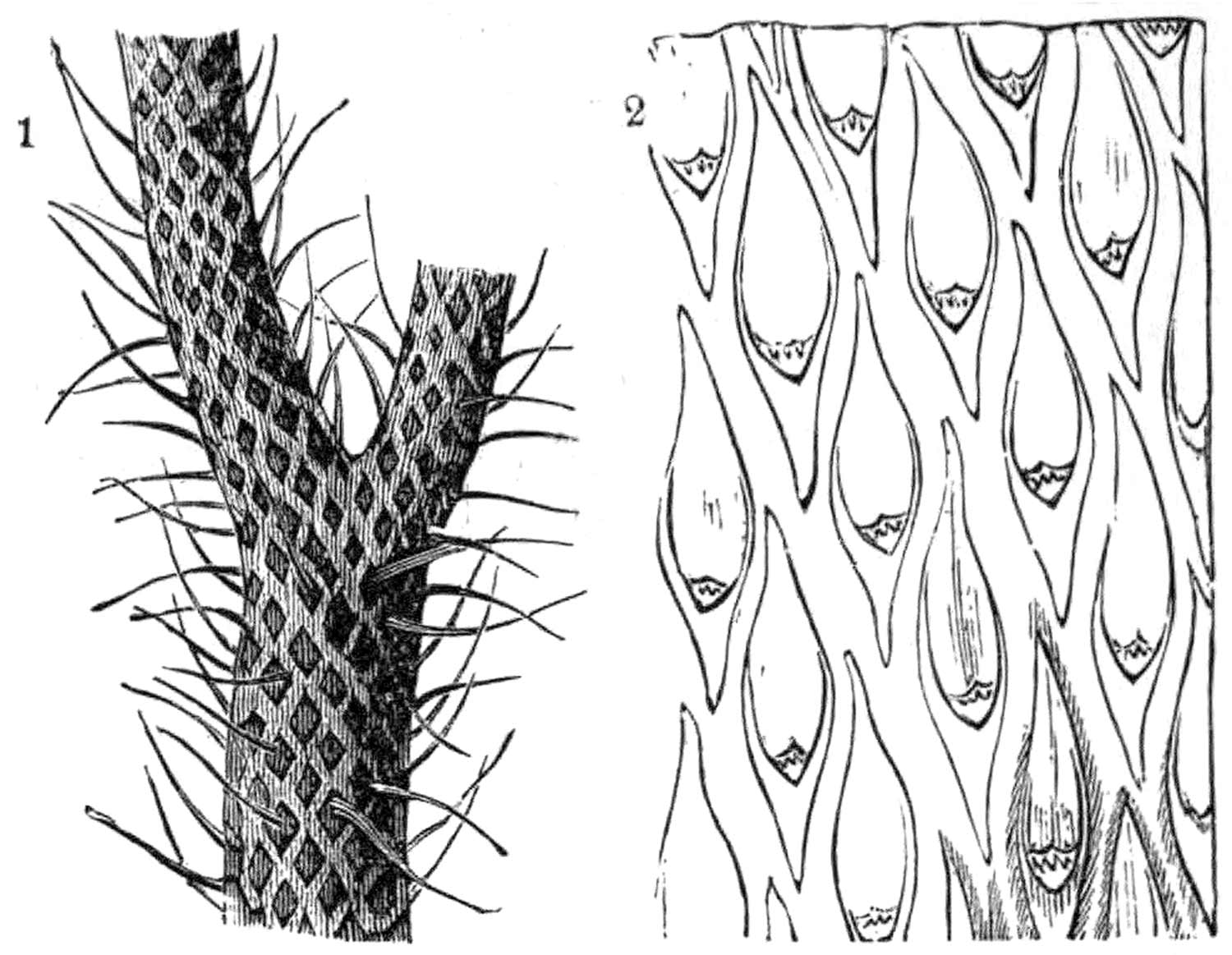

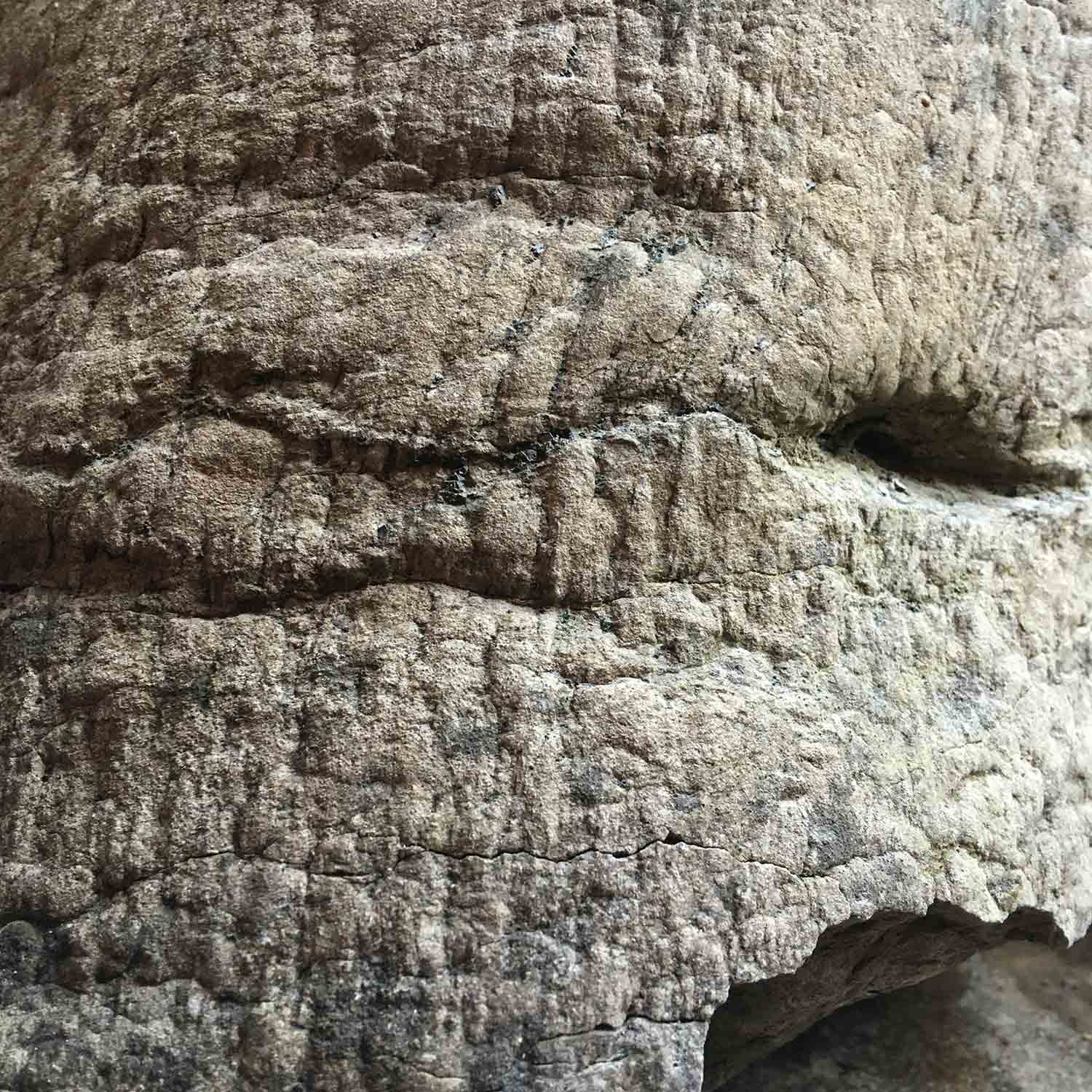

What you’re seeing are fossil impressions of the texture of a Lepidodendron “scale tree” in both a large hunk of bituminous coal and a piece of mudstone. They were not found together, but both are from deep underground in what is currently Mingo County, southern West Virginia.

This is prehistoric tree bark, of a sort, and we’re only seeing it because people pulled it out of coal mines. A friend who mined underground in the 1970s and 80s told me he once worked in a “room” where he was completely surrounded by ferns and “small snail-like things”. I’ve thought often lately about how that must have felt, to be the first to see these shadows of a fern grove in the dark, illuminated only by harsh electric bulbs or, in another era, tiny acetylene flames bouncing just above your eyes from a tin lantern.

Below is a “Kettlebottom”, a fossilized tree trunk. Usually found in mine roofs, kettlebottoms are lethally dangerous to miners: they can drop unexpectedly, are often difficult to locate, they’re soaked wet when buried underground (adding to their weight when they fall) and are quite dense. The one I’m holding is heavier than you might expect.

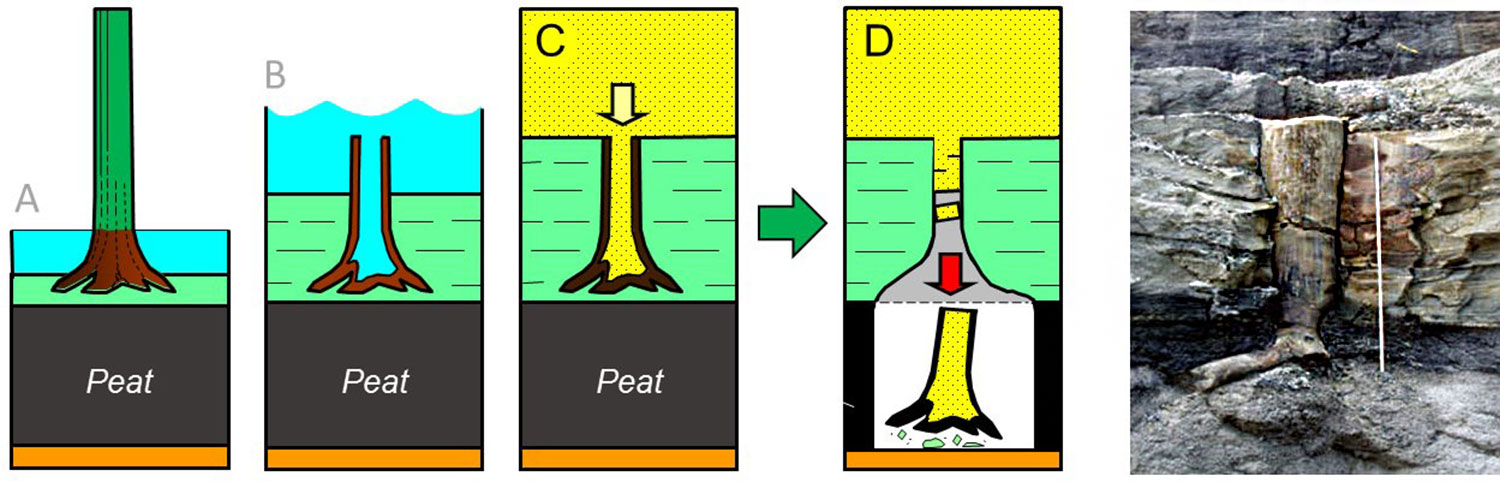

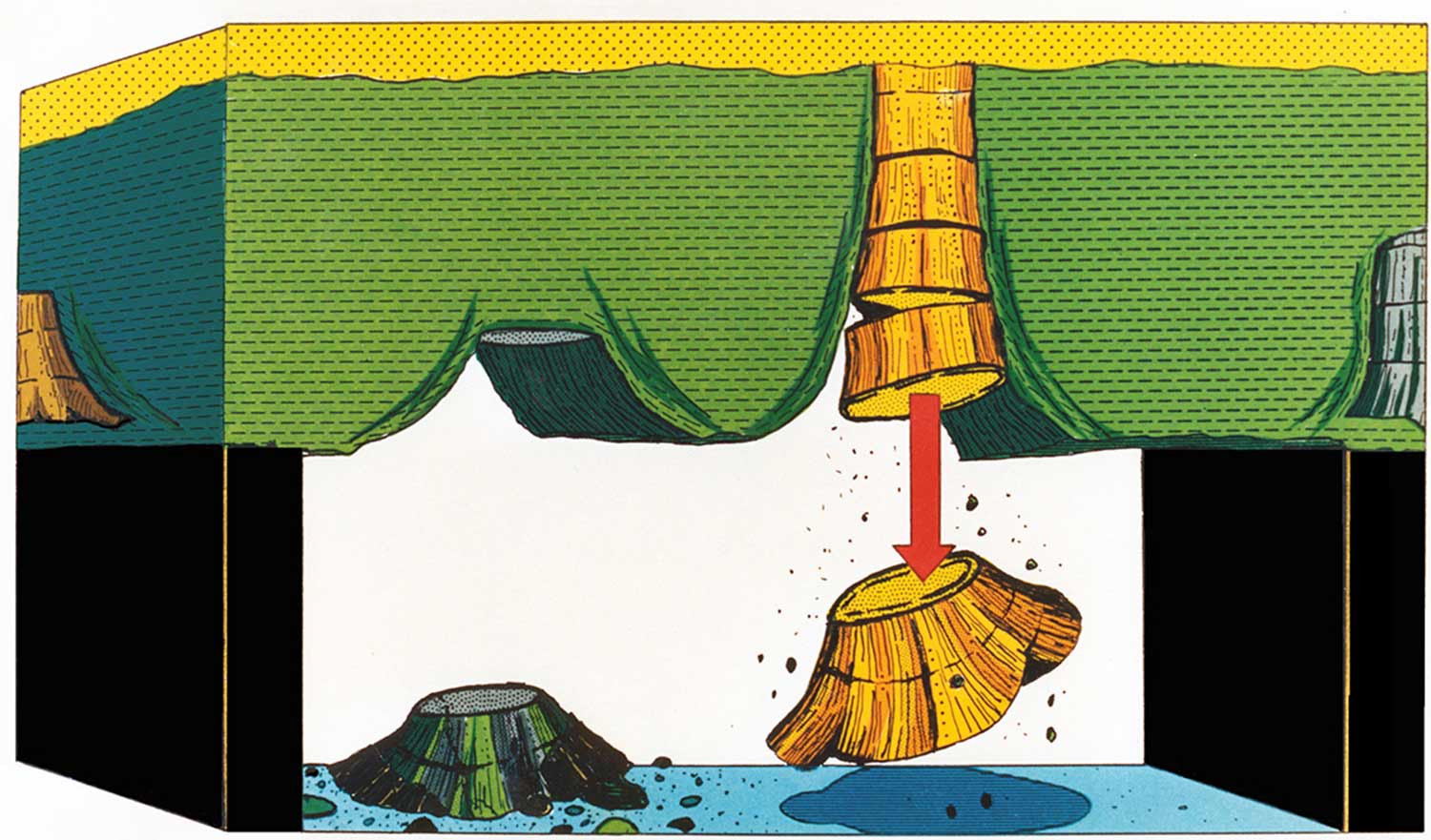

The fossil stumps found in the central Appalachian coalfields are the remnants of wetland trees from +300 million years ago. If you’ve ever seen a tree sticking out of a lake after a flood, or growing in a swamp or wetland, these are them.

Depending on where and how the particular tree in question decomposed, a kettlebottom can be either an interior or exterior cast of the stump. The one we’re putting on display at the Mine Wars Museum is an external cast, so you can see the patterns of the bark and some ripples in the surface which look just like a tree you might find today.

These illustrations are from the University of Kentucky’s Geological Survey, which is a fascinating and accessible wormhole which you might enjoy shooting right down into if you’re curious about more paleontology and mining in Appalachia.

Although every current timeline is now up in the air, I’m still plugging away at design and fabrication work for our museum. I had originally planned to write most of the posts on this channel later this year, as points of reflection, but it looks like I might have more time for reflection this spring. So, stay tuned!

Bonus: spend a little time with artist Justin Berry’s subtle animations of the original woodcut illustrations form Georgius Agricola’s De Re Metallica (1556). “By making the original subject of these drawings—the human intervention—vanish, Justin Berry creates a new illustration, which focuses on the landscape itself.”