Echoes of colonialism and dispossession, enacted in the daily rituals of eviction and speculation.

In her eviction notice to us, Tatiana Omran writes that she has been saving to buy her own house, her dream to live in our neighborhood. The evictors speak of how they enter our house, “fall in love with its San Francisco charm,” its sunny windows, the little room where they can see themselves doing yoga. They speak as though it is an empty house, vacant, open and receptive for their use. Where have we heard that before? Vague echoes of a “land without a people” for those who want land. Somewhere in this city, I’m sure, I can count 418 homes, forcibly depopulated and occupied. Many more.

Tatiana and her parents are landlords of our home. Her parents, Peter Omran and Tanya Omran, run a nonprofit aid organization, Heart of Mercy International.

I want to give them the benefit of the doubt. I want to think these people are not evil in the way serial evictors who buy buildings full of seniors to clear them out and flip the buildings at a profit are evil. The Omrans’ actions are perhaps more the banal sort of evil, caught up in the ways capitalism and colonialism molds all of us, everyday injustices ingrained into a system that tells them it’s all right to do this, even if they are religious people, even if they think of themselves as socially responsible, even if they have their own historic ties to the impacts of colonial dispossession and displacement. The system tells them that it’s all right to buy our homes and move us out just because they want them for themselves or for profit, because their money make it all right.

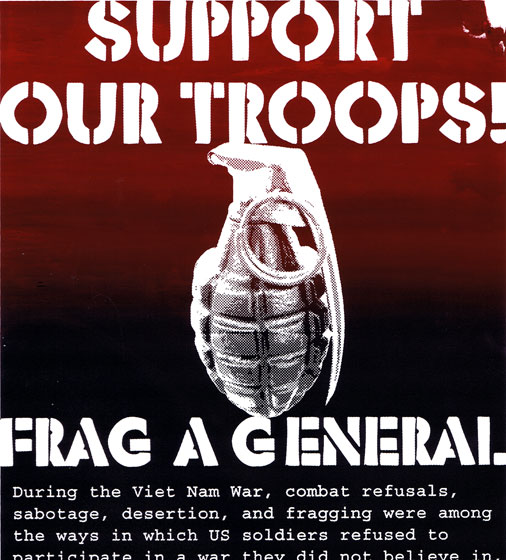

They’re probably confused by us. They are probably thinking, “Why won’t they just take our money?” To them, our fight is simply a negotiation for a buyout, a line item in their financial calculations. In this system, the landlord expects the passive tenant, “Pay your rent and stay quiet.” We fight to make our living, and the rentier class extracts more and more of our lives. Who made those rules? The speculators expect that no one fights an eviction: a hint of harassment, a threat of not having the proper papers, is enough for the tenant to self-evict. In the best of cases, they give an “offer” of money coupled with the threat of eviction.

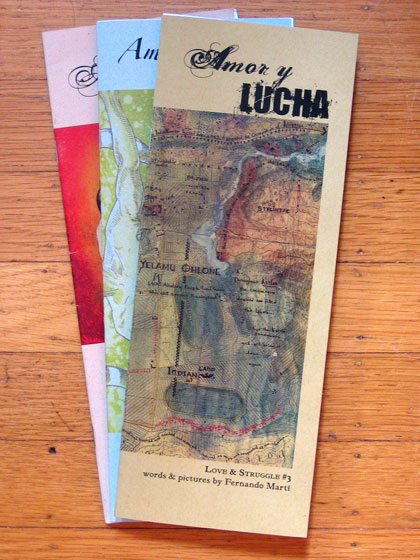

We adapt, we can change, we can move. Can I find another home for our family, that we can afford, that retains those connections to our community, to our child’s school, to the roots we’ve laid in this city, without having to resort to evicting another family? Perhaps. It will take time. We might never find it. A “buyout” in these conditions is never a gift, not an offer given freely. It is either the lie of $24 in gaudy beads and trinkets, or it is the cover for the threat that backs it up: harassment, eviction, trial, and ultimately the weapons of the sheriff’s deputies standing at your door. We are very aware of our own privilege in this fight, our location in this system as non-native people residing on these lands: Yelamu, traditional unceded Ramaytush Ohlone lands, people still fighting for access to their ancestral homelands, for sovereign recognition and rights.

I would hope as people of faith, as people who have suffered under colonialism and displacement, that they would do the right thing and call off the eviction before we end up in court. I think of the words of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish:

I have learned the words of blood-stained courts in order to break the rules.

I have learned and dismantled all the words to construct a single one:

Home.

Even if these particular people ultimately do the right thing, the system will continue to condone this behavior, one after another, in workplaces or home places, treating people as money. A system built on greed, built on displacement and dispossession. Our fight is for all of us, tenants, who believe we have our own right to the city, not dependent on how much wealth we have. The fight is to change the system, to build a more ethical structure, where this kind of banal evil, where money, power, and claims of “ownership” trump humanity and empathy, is no longer a pillar of the system.

If we are indeed evicted, we will not end up homeless – we will be able to land on our feet, even if perhaps no longer able to afford to stay in the city we call home.

But the through-lines are painfully visible, from colonial occupation writ large to the small individual acts of eviction and dispossession that re-enact colonialism on a daily basis, here and abroad. We are all implicated in this system built on greed, built on displacement and dispossession. From Palestine to Ohlone lands, colonialism follows us.

In a system that tells the owners of property that they have all the rights, we have to organize, we have to fight back, in the streets and in courts, to remind them of what’s right.