I just received some great documentation by Mark Williams of my ¡Graphic Liberation! exhibition and workshop at Colgate University. I’m going to use his photos to walk everyone through the project, which has been really important to me as it collects decades of research and work.

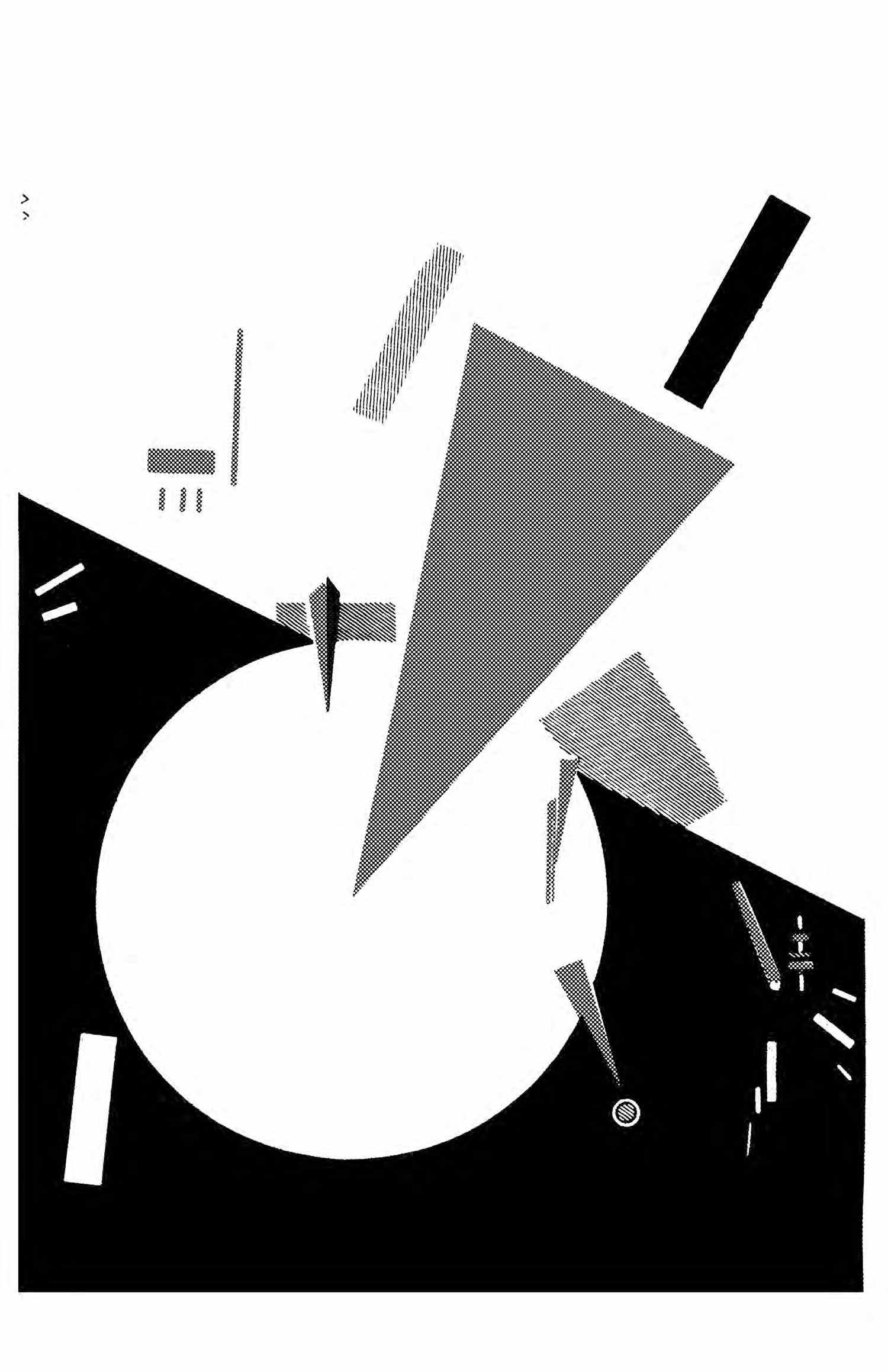

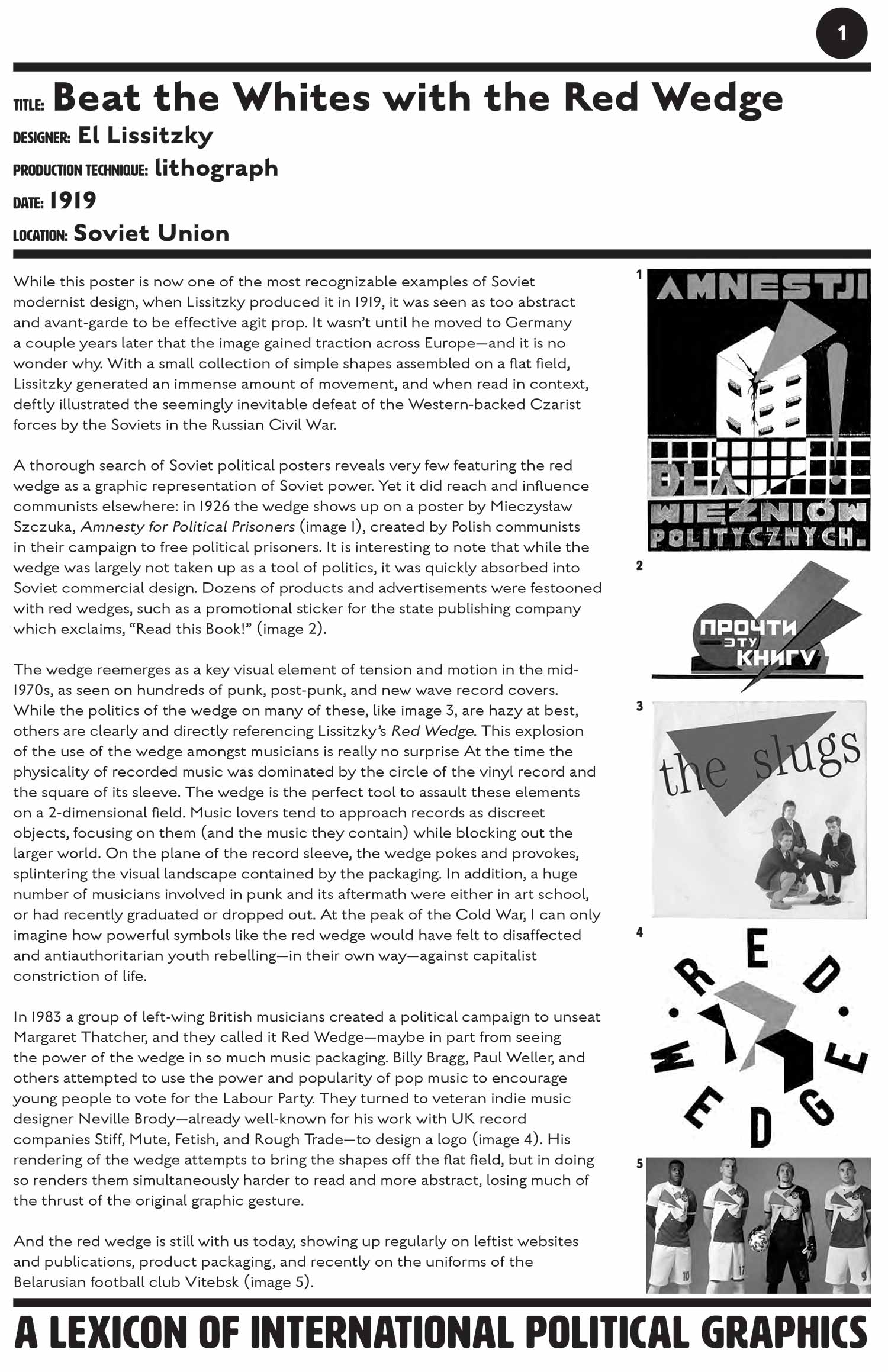

One of the main anchors of the exhibition is the project A Lexicon of International Political Graphics. This consists of one hundred 11″x17″ 2-sided vinyl panels. Each panel features a black and white political graphic on its face, with a visual history and the social context of the image on the back. For example, here is the panel for El Lissitzky’s Beat the Whites With the Red Wedge:

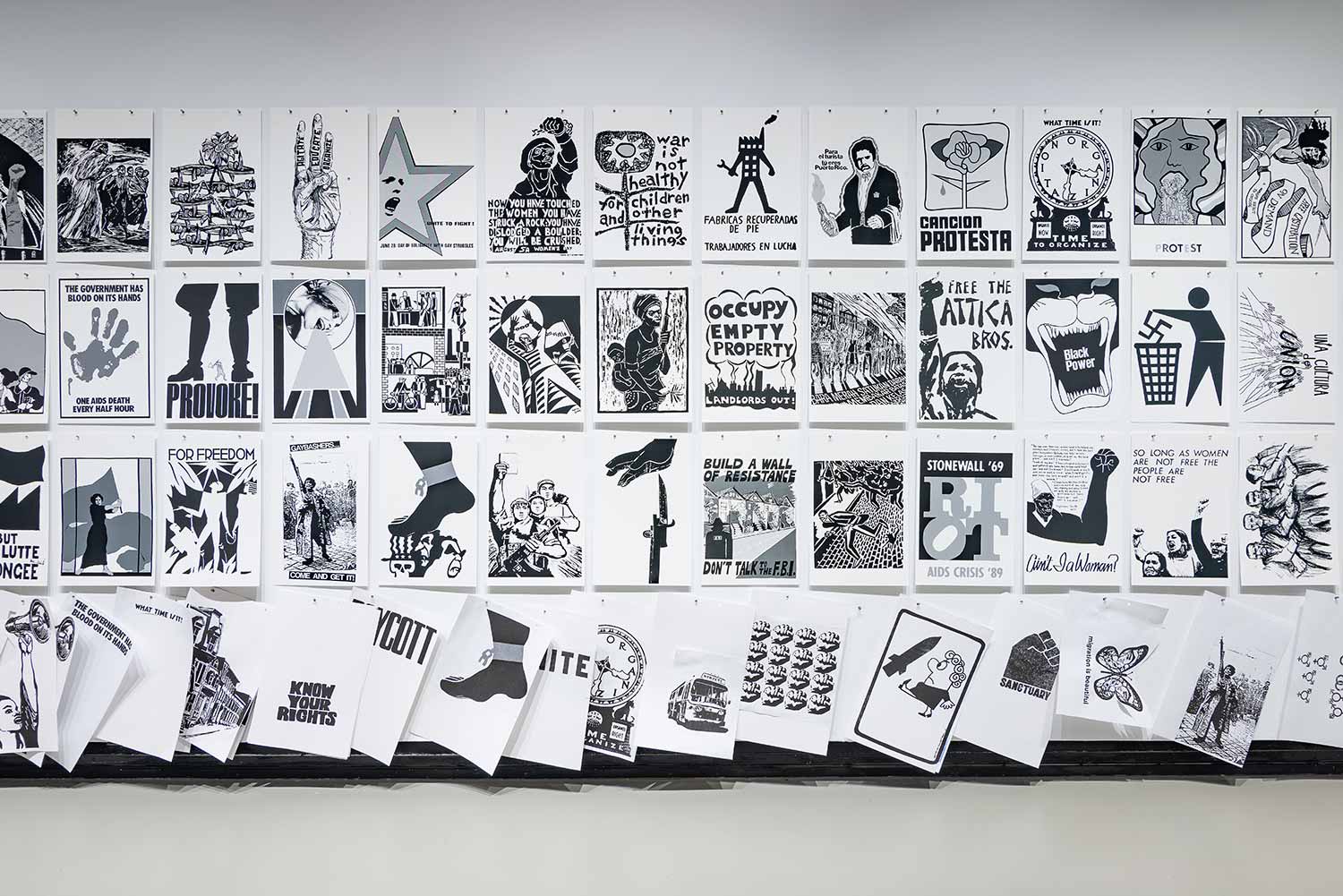

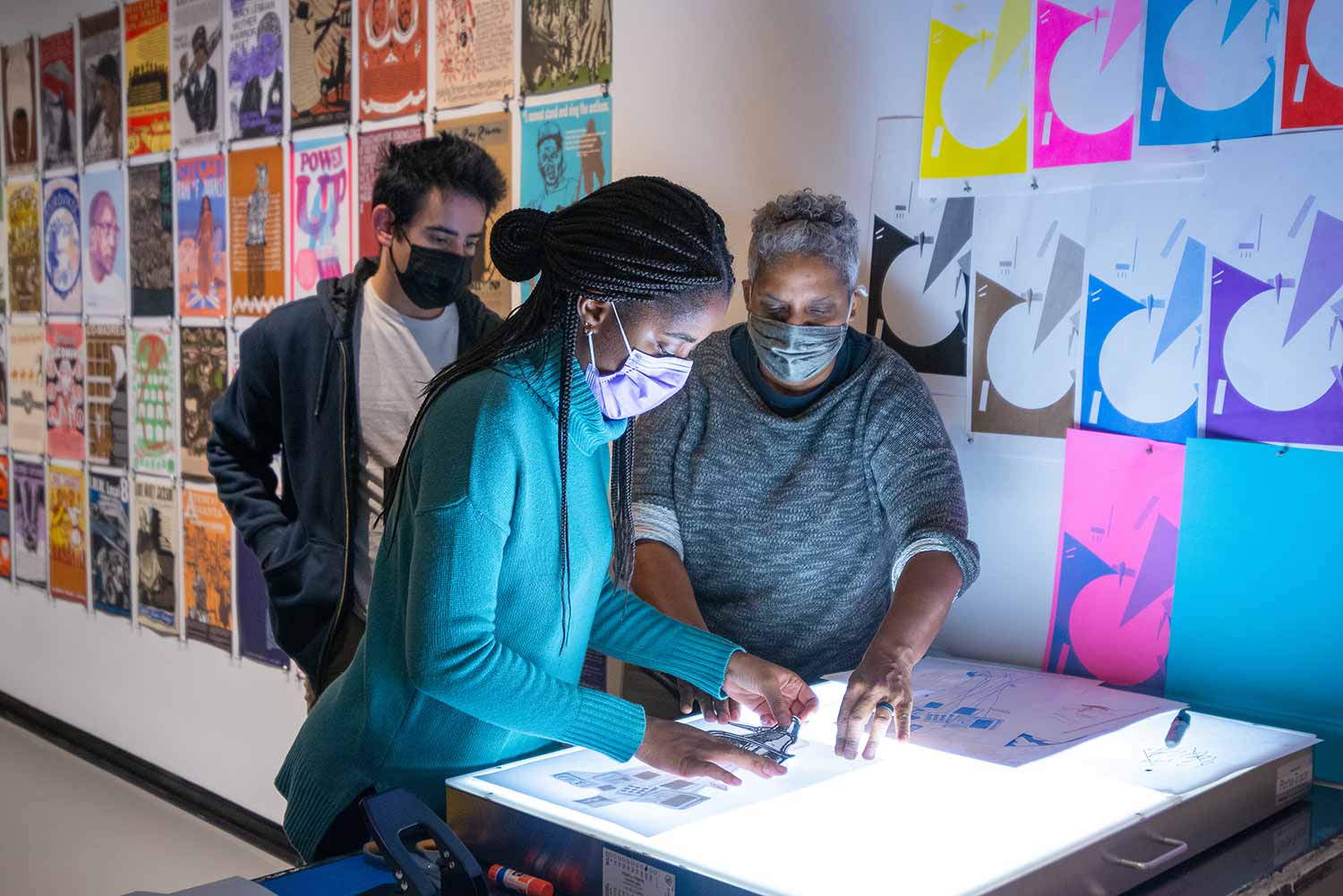

These panels all hang in a giant grid, each easy to take down, turn over, read, and most importantly, use as a master to make copies of at the risograph printer stationed by the Lexicon:

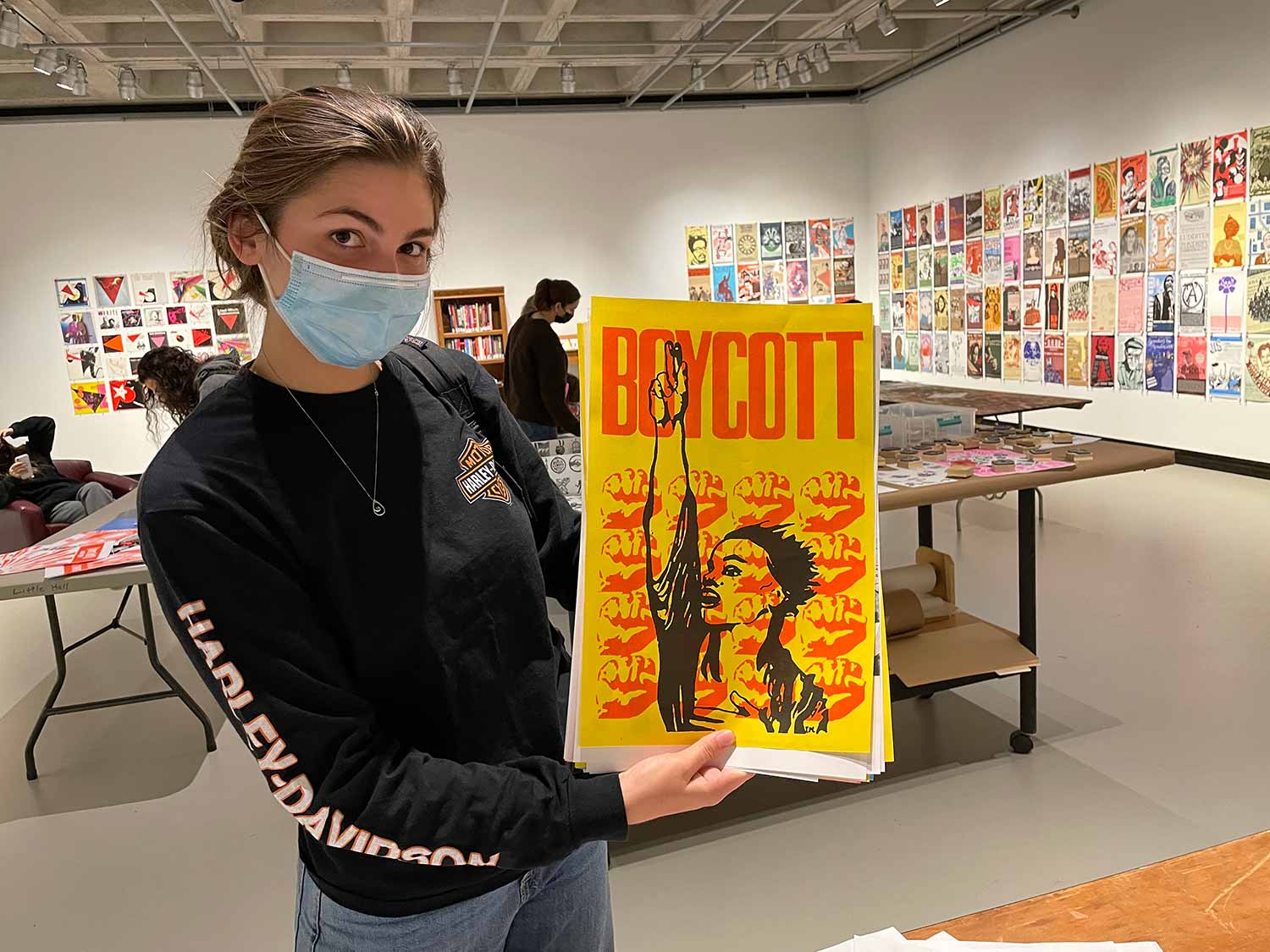

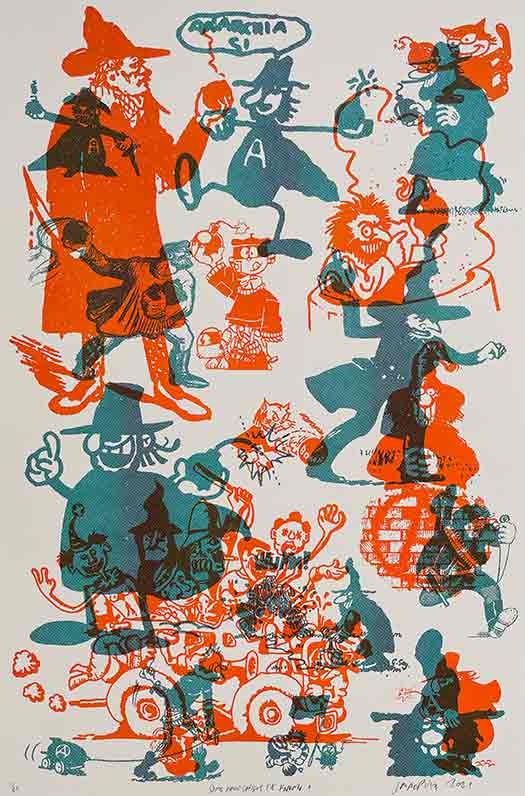

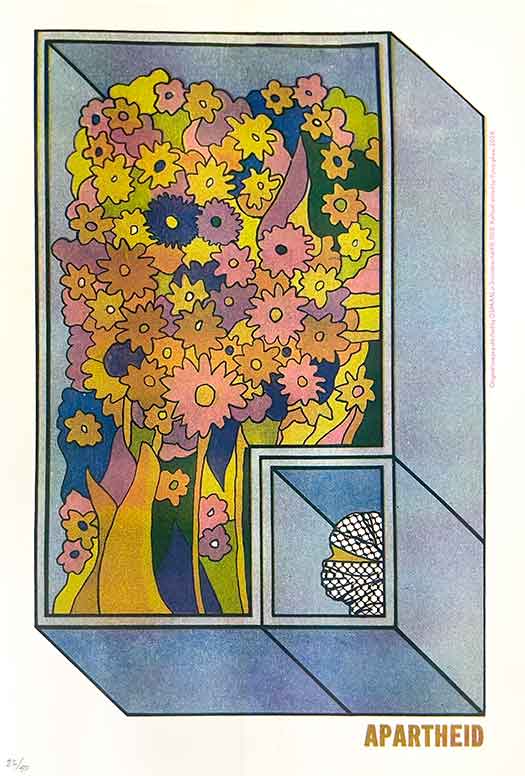

The imagary on the panels are drawn from over 200 years of political graphics, from well known socially-engaged image creators such as Käthe Kollwitz and Jose Posada to ad-hoc protest groups like the Atelier Popular (France, May ’68) to movement collectives Medu Arts Ensemble (anti-apartheid cultural group in the early 1980s) and Taller Popular de Serigrafia (Argentina, early 2000s). I’ve assembled these 100 images—by almost as many makers and from two dozen countries—for a number of reasons. One, to begin to map out a visual language of solidarity, human liberation, and dignity which has evolved and been built across the borders of time, nation state, and spoken/written language. When looking at this image history we quickly see that a number of visual gestures, icons, and techniques are repeated over and over again, whether it is a raised fist, a red wedge, or bars being bent or broken. I like to think of this history on the terrain of language rather than art because unlike traditional art practices, it is not authorship, newness, or scarcity that gives the images value or power, but instead repetition, iteration, and use. Collectively they form a tradition and a lineage born out of working class solidarity and embracing anticolonialism and anti-imperialism, feminism and gender justice, racial equality, and all movements of human and planetary liberation.

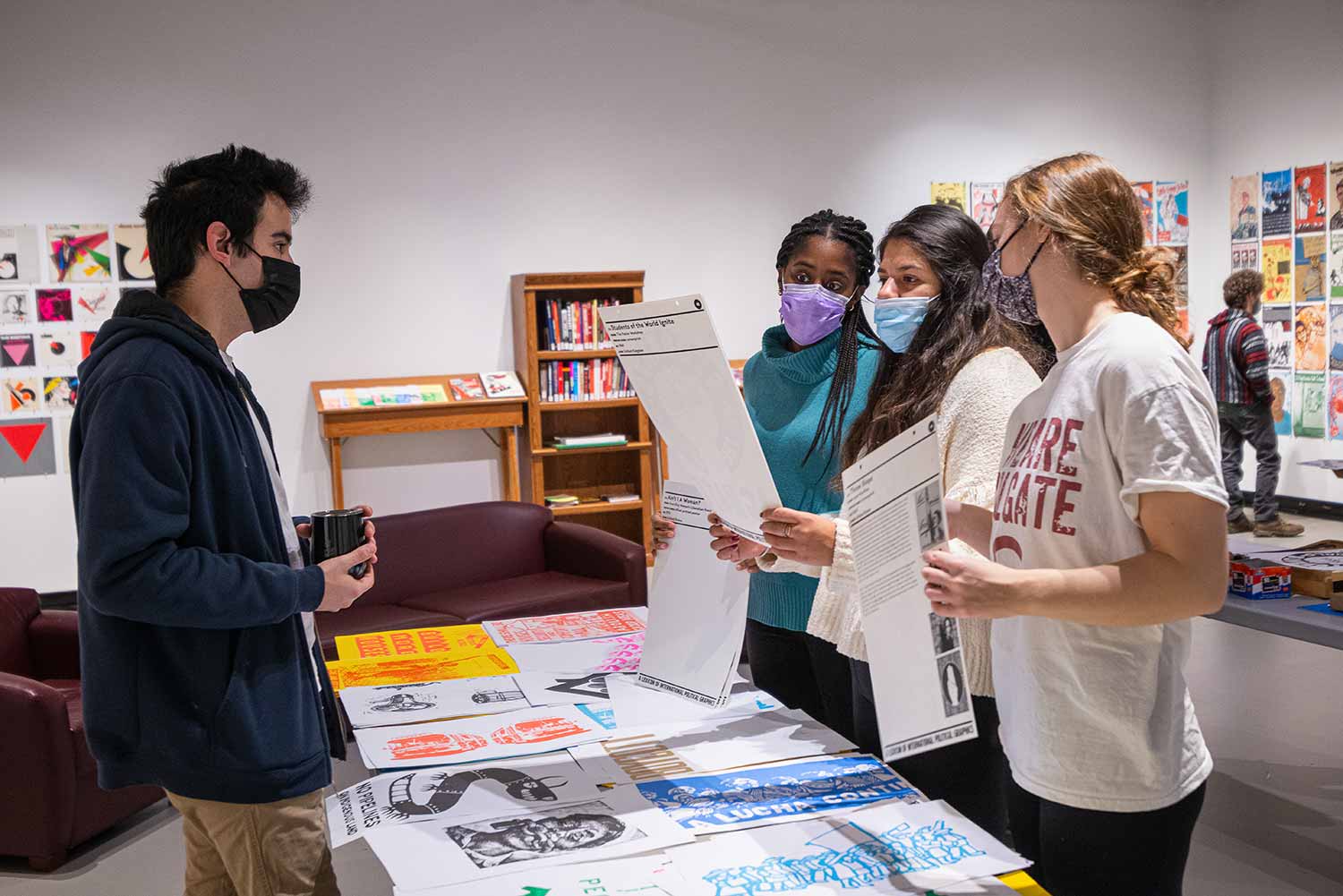

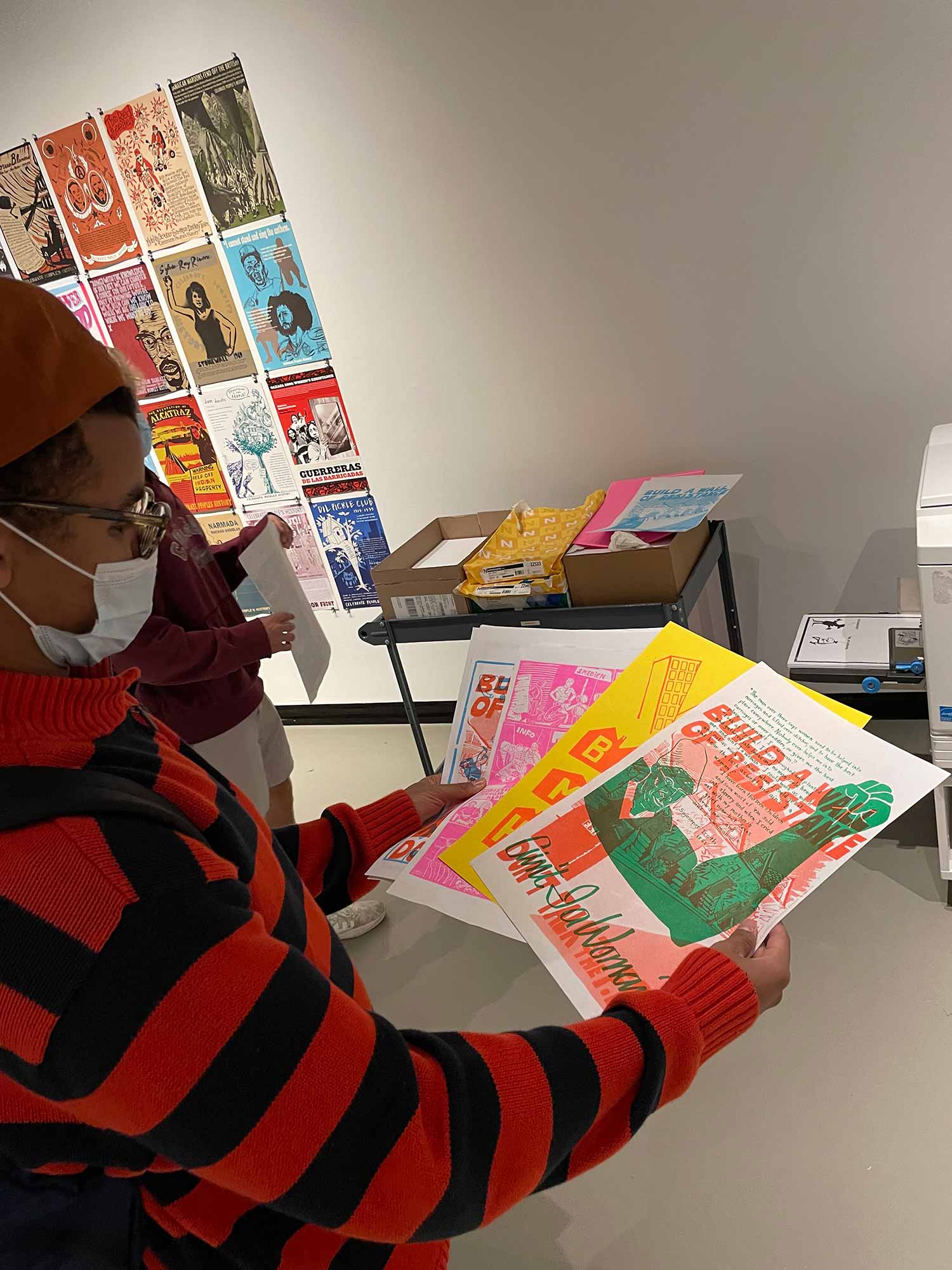

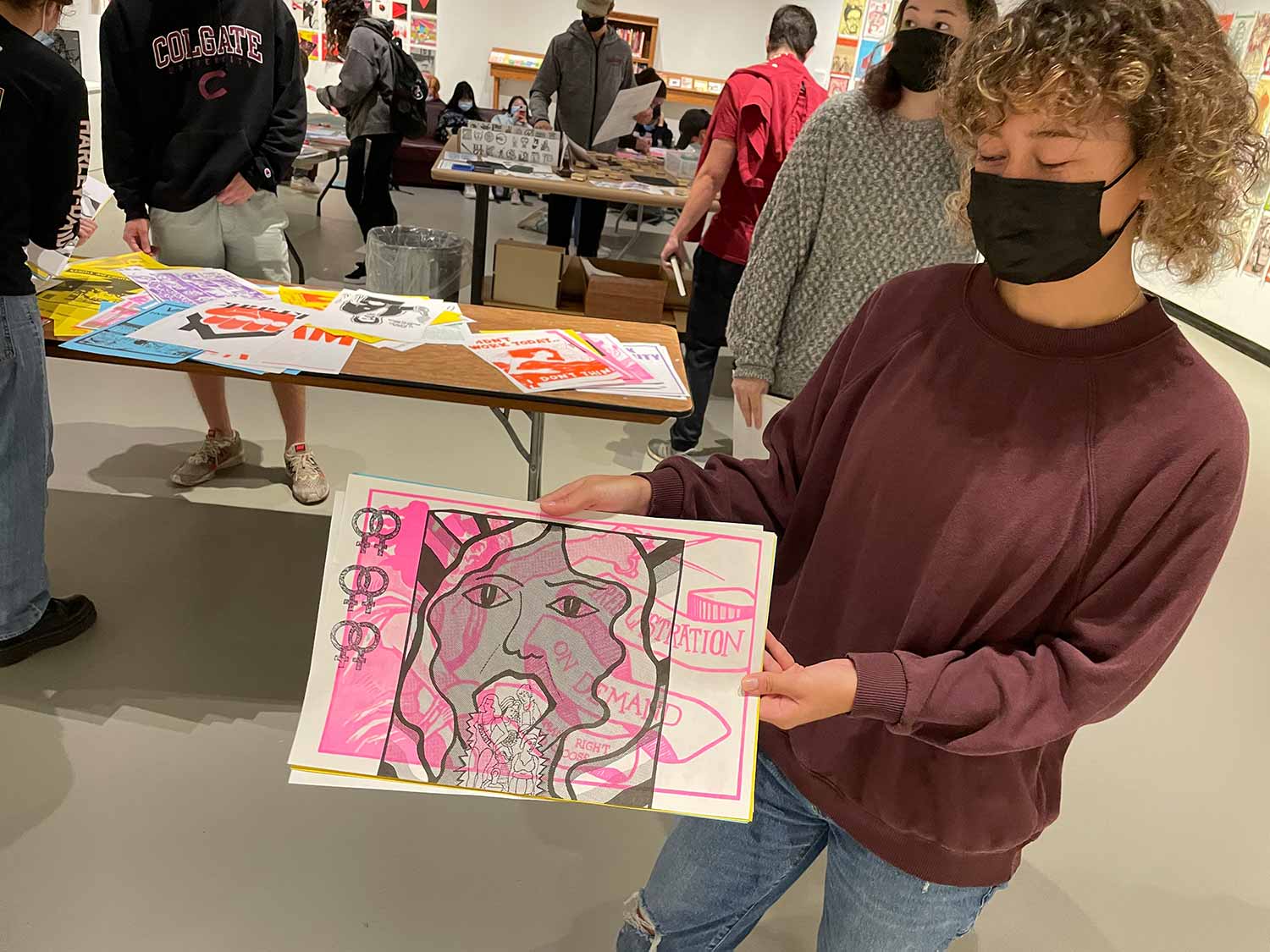

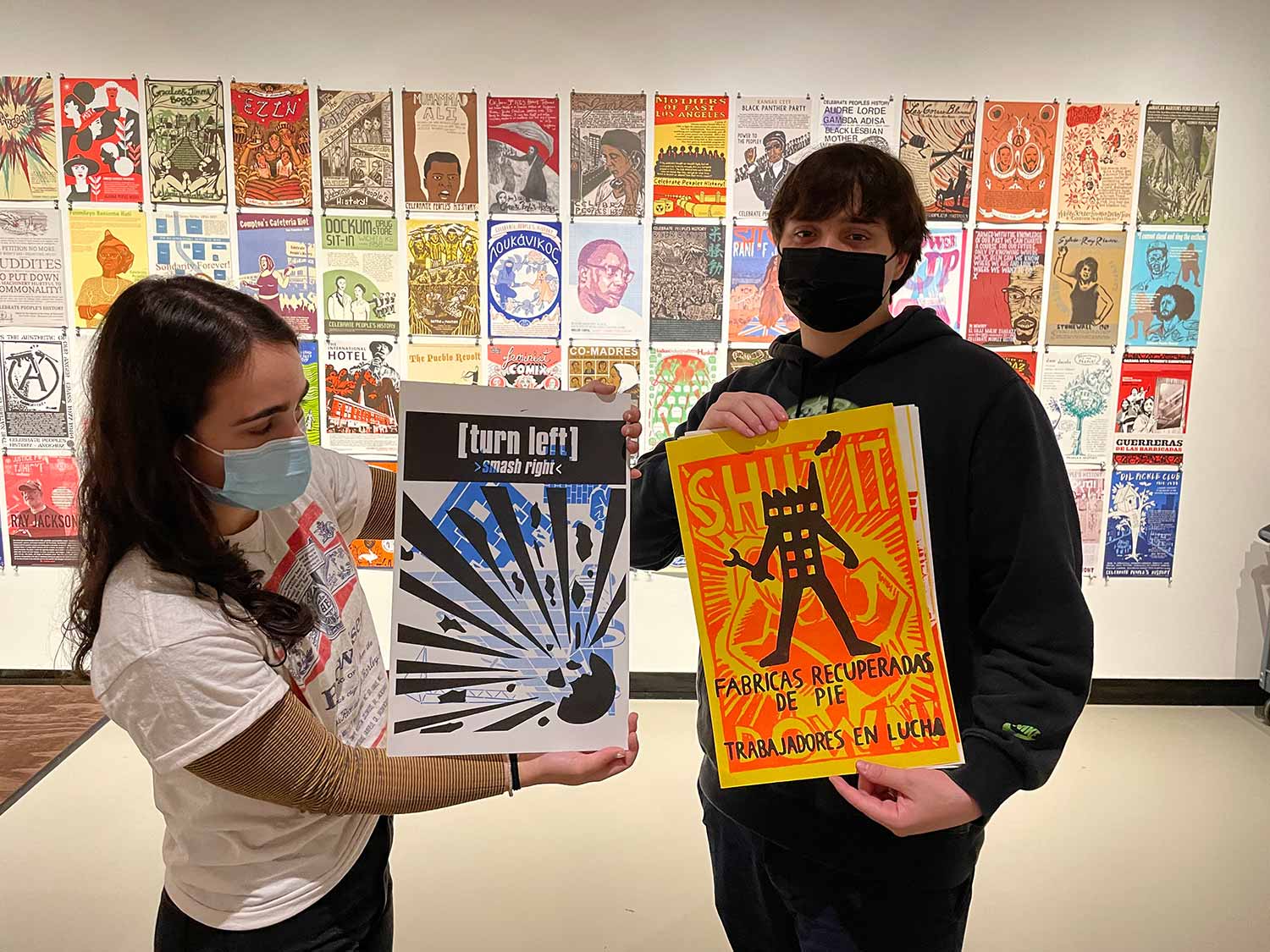

Each of these panels is a “sentence” or “paragraph” in the visual language of solidarity and resistance. And like other languages, these phrases and slogans take on different valences and evolving meanings in different times, places, and contexts. Most importantly, these graphics were created with the intent to be used, they circulated initially within social and political movements, and elements in almost all of them were picked up and repurposed by other movements. To that end, anyone coming to the exhibition is encouraged to use this Lexicon, to remix the imagery and create new posters about issues that are meaningful to them. To that end, hundreds of students at Colgate did just that:

As an extension of the Lexicon I installed another project, Icons of Resistance. If the Lexicon is, as I said above, sentences from this visual language, the Icons are letters and simple phrases. Each Icon is a 2″x2″ rubber stamp, of which I’ve made over 150. Anyone in the gallery is encouraged to play with the stamps and integrate them into the poster making being down with the risograph.

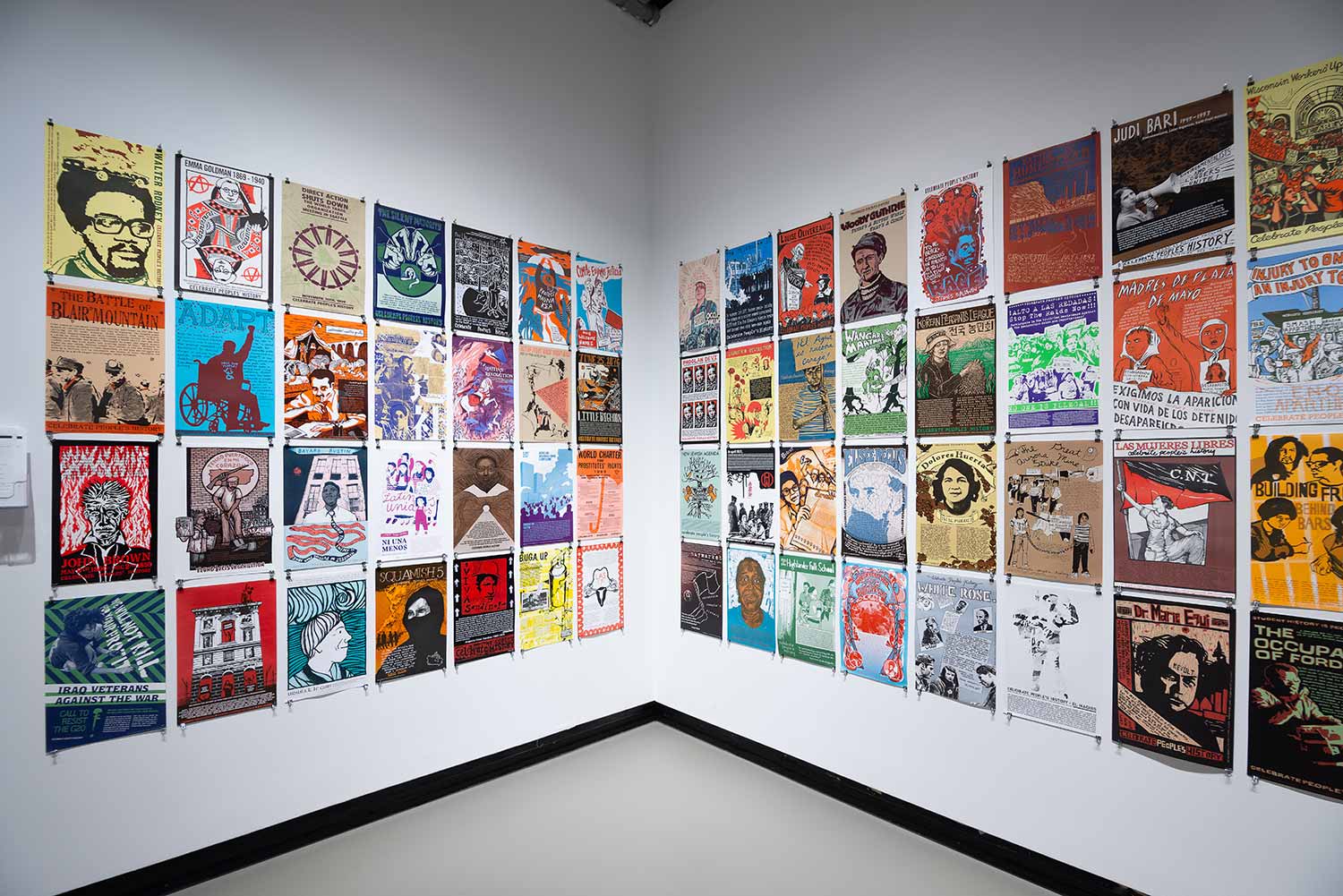

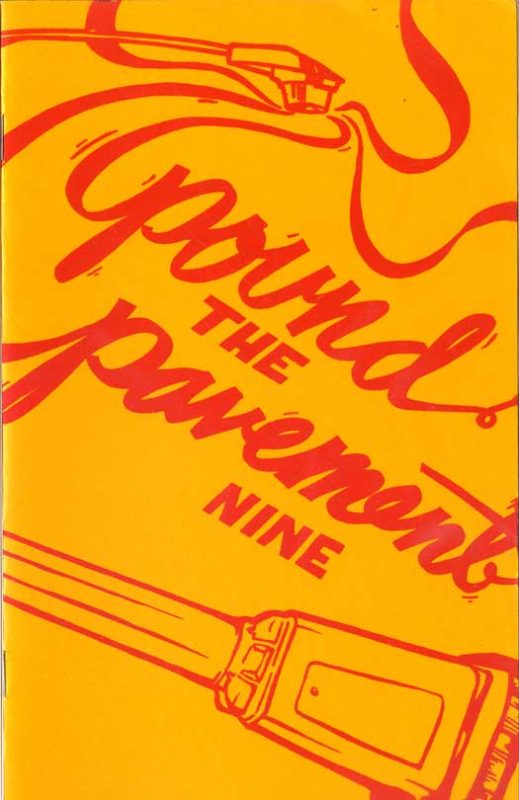

Spreading along two walls across from Lexicon is installed 150 posters from the Celebrate People’s History series. This grid of 11″ x 17″ posters mirrors the Lexicon grid, but is a riot of color. Like its counterpart, these posters were created by over 100 artists, writers, and designers, and in addition include many bits and pieces of the visual language of protest I’m highlighting in the exhibition. The People’s History posters function as an object lesson in the myriad ways this language is used.

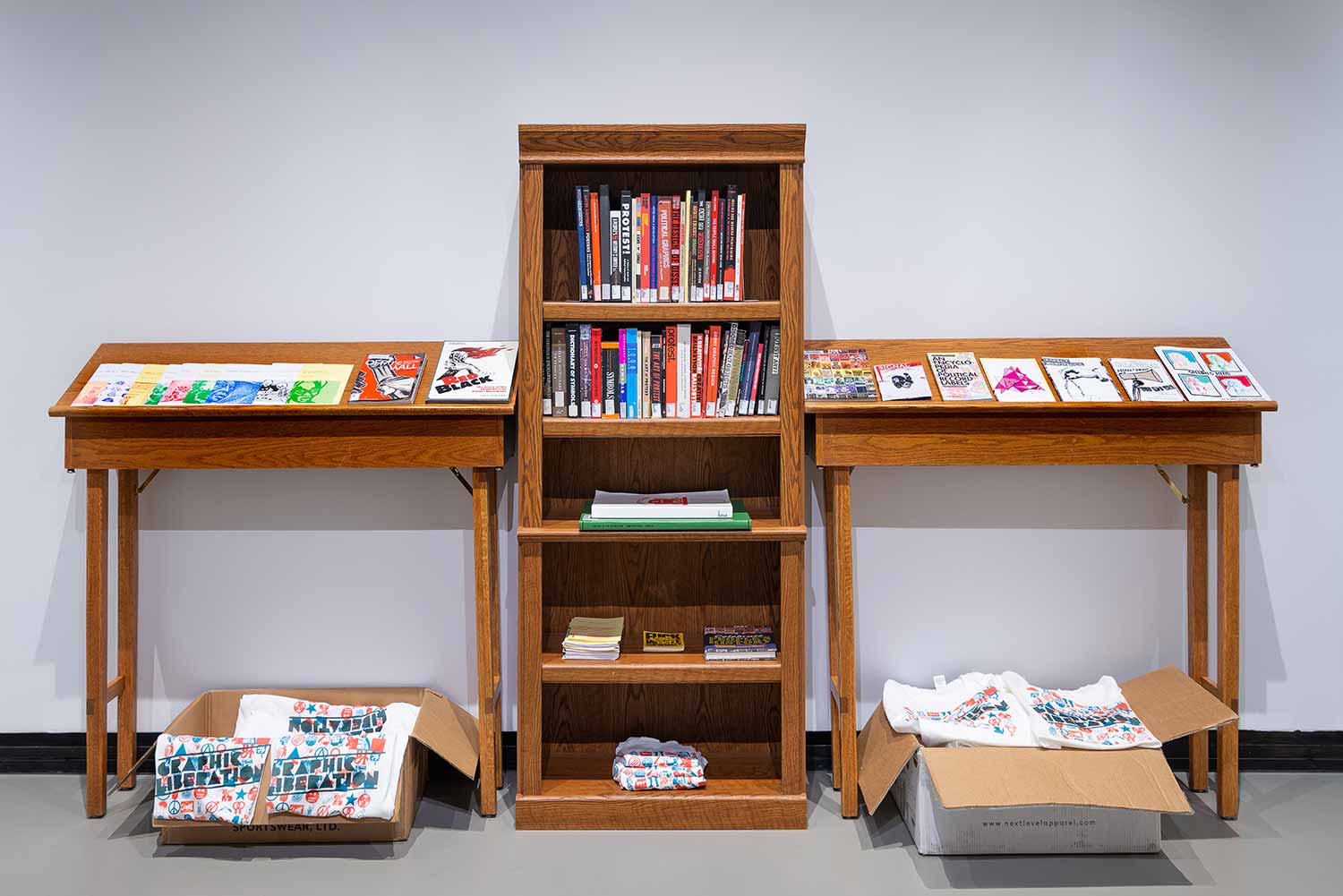

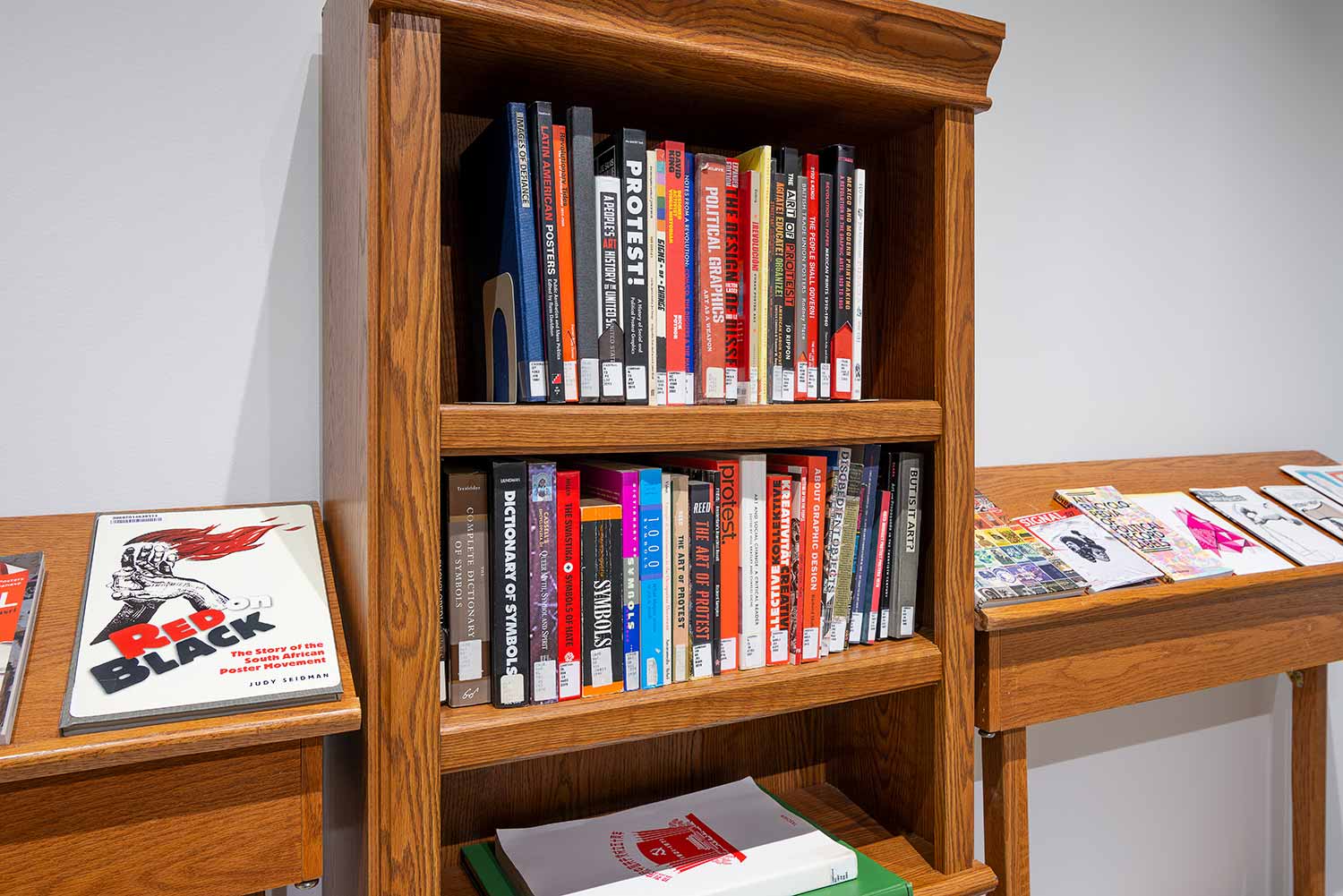

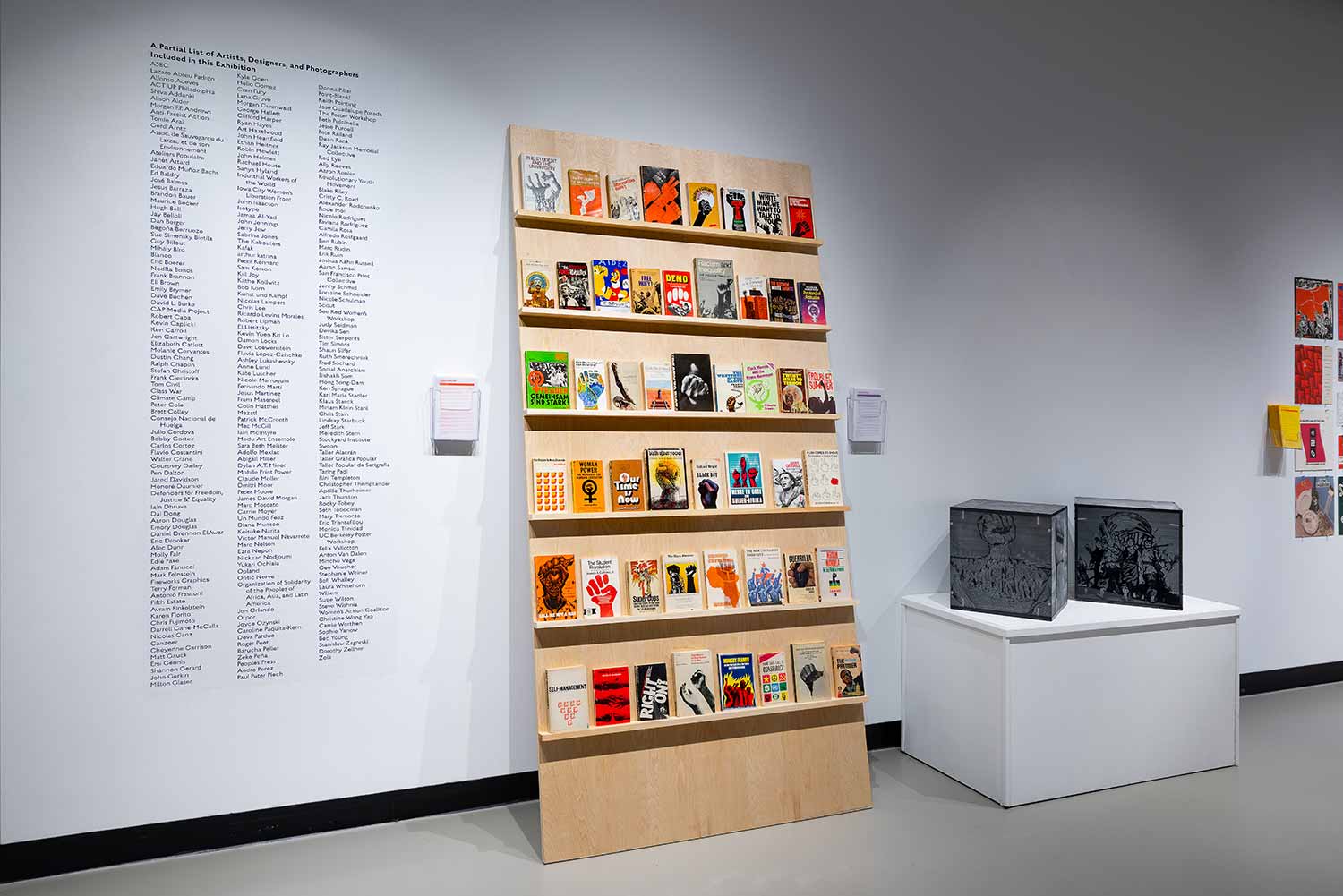

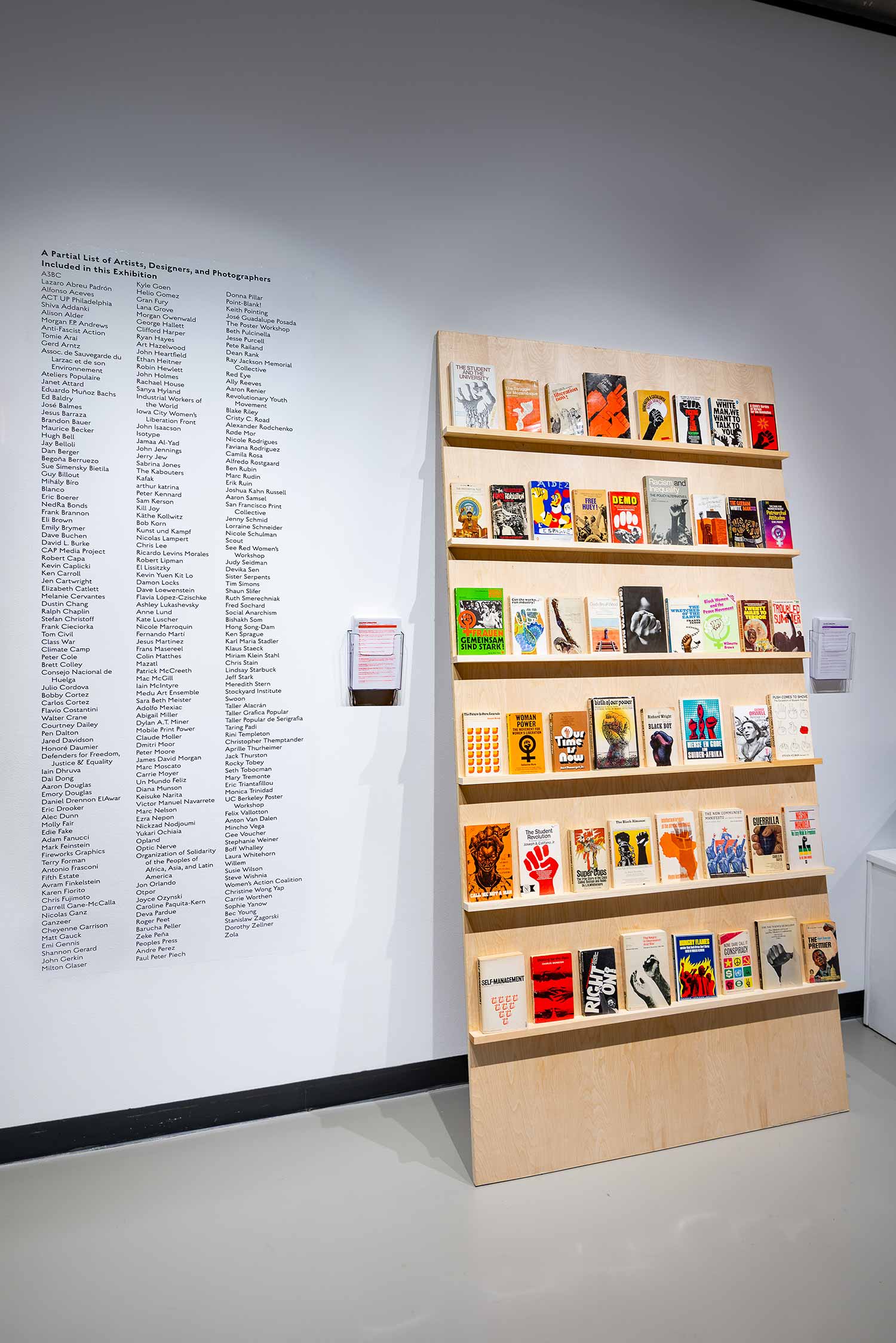

Next to the People’s History posters is a set of shelves which contain a selection of books about political graphics, posters, and the culture of social movements, all part of the Colgate University library permanent collection. This mini-library, or reading area, allows for further research into the history of image making and political movements.

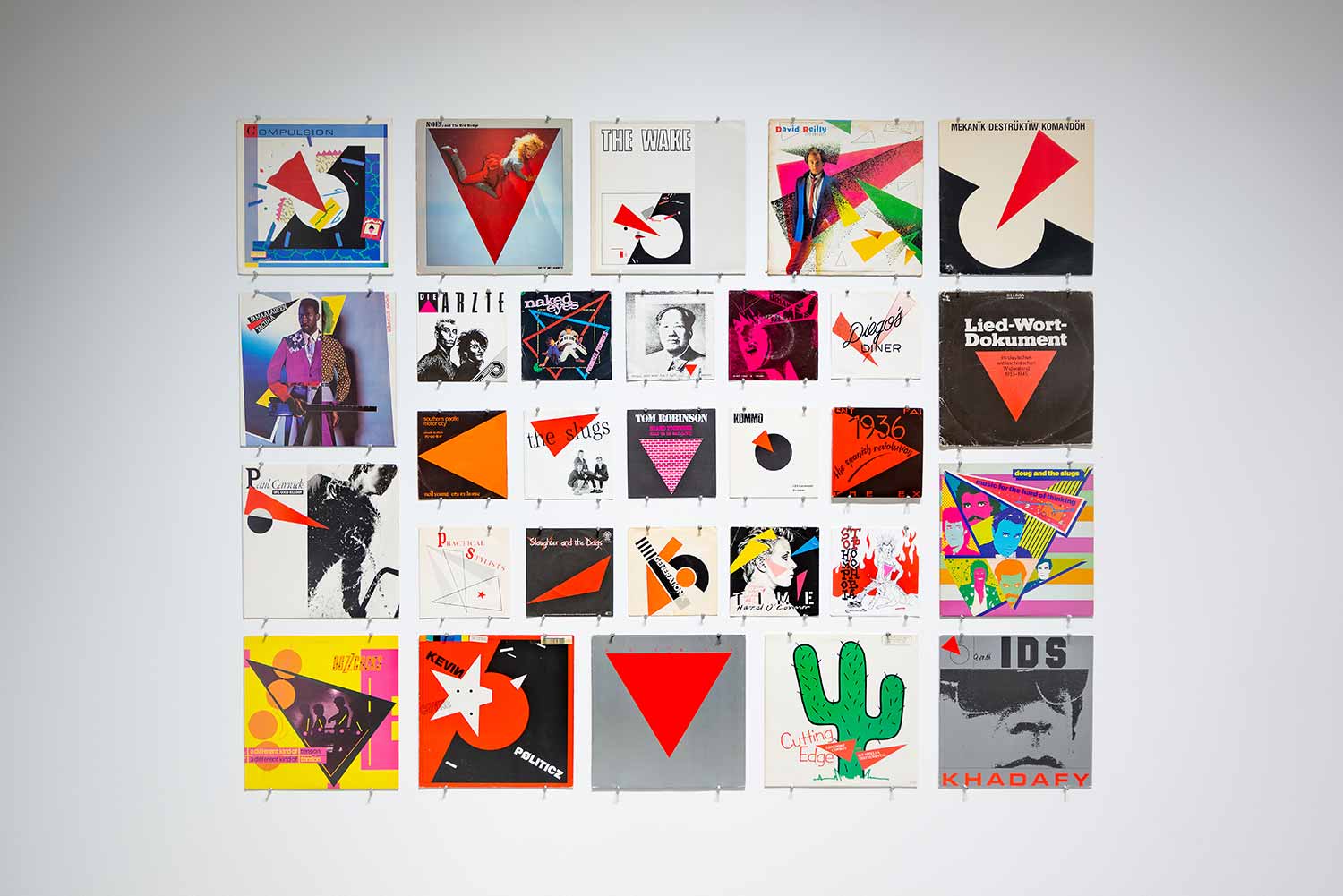

The final sections of the exhibition are all explorations of the ways the visual language of liberation weaves in and out of different spheres, in particular popular culture. I’ve assembled two different sets of vinyl record covers, together titled Flags, Wedges, and Triangles. These fifty-eight record sleeves range from being explicit and didactic parts of political movements (such as records released by labor unions and solidarity organizations) to punk, new wave, and dance music, some of which is politicized, others simply borrowing the “edginess” of a protest aesthetic. Next to the records is a collection of fifty books, all of which feature raised fists. The books range from Black Power mass market paperbacks to feminist classics, student organizing manuals to African novels. One of the reasons I find these collections of mass produced objects interesting (beyond my own admittedly obsessive collecting tendencies) is that they show how these politicized gestures and images can be recuperated to sell products, but rather than neutralizing their use and meaning for political movements, this arguably has little effect, or even makes them more powerful. A red flag on a pop record cover (or a grocery store logo, for that matter) is not going to make any difference to the millions of communist farmers and workers from India to South Africa flying them everyday.

At the time of the install, one last project, a set of 6 16″ x 16″ plexiglass cubes, wasn’t yet completed. When finished, the thirty-six sides of these cubes will tell a story of the raised fist, from a 13th century BCE Mayan dagger hilt to Honoré Daumier’s The Uprising to the Spanish Civil War to Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the Mexico 68 Olympics to the fist emoji on all our phones. Here are two of the cubes. Ultimately these cubes will both function as art object but also printing plates. Each side can be inked and printed from just like you would print a wood block:

In addition, I compiled a soundtrack of over fifty political and social movement songs which ran on a loop throughout the gallery (the playlist can be downloaded HERE), and the conversations I’ve been holding with other graphics producers as part of an ongoing zoom discussion series were playing on a loop in a small black box viewing room attached to the gallery.

While I spent months assembling all this material—and arguably most of the last 25 years!—this exhibition clearly collected the work of hundreds of other people. For the Lexicon and Icons projects, I contacted many of the artists I know or knew how to get in touch with, explained the project, and paid them a small stipend for using their work. For the CPH poster series, I also pay artists for their poster designs. But in reality in both cases this is just a token, a gesture, and the hope is that artists will recognize that what I am trying to do here is extend the life of the work, bring it to new audiences, and continue to make it socially relevant in the world. I also generated a list of all of the artists and designers I could identify whose work is included, and filled a portion of a wall with their names. I wanted to make it clear that while I believe authorship in a capitalist society can be harmful to the political potency of cultural work, I also have no interest in stripping it from anyone or anything, and it can be quite useful for accountability, context, and historicization:

More photos can be seen HERE. This exhibition could never have happened without an immense amount of support from Colgate University, and in particular DeWitt Godfrey, Angela Kowalski, Lois Wilcox, Lynn Schwarzer, Brynn Hatton, Mark Williams, Duane Martinez, Heidi Eakin, Sarah Curtis, Kevin Donlin, Lara Scott, and all of the students and gallery goers who used the workshop.

I’m very excited that a new iteration of Graphic Liberation! will be traveling to George Mason University in January, and a number of the projects included in it will also be featured in my upcoming exhibition We Want Everything, opening at the Cleveland Institute of Art on April 1st, 2022. More on those soon!