This is the first in a series of posts about a visit to the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Eastern Washington state, and the fate of the uranium ores found in the Shinkolobwe mine of Katanga Province, DR Congo. Say tuned for upcoming installments- I was originally going to post this all at once but it’s become too lengthy for one post so I’m going to break it up and parcel it out as I get it done. All photos taken by Erica Thomas.

The Hanford Nuclear Reservation is the name given to a sprawling reach of grassland in Eastern Washington state, north of the Tri-Cities and gripped in a crook of the Columbia River. You can see it on Google maps, a dun lozenge of desert surrounded by the varied green dots of center-pivot desert irrigation, but for fifty years it was one of the most secret and isolated locations in the continental US, the site of numerous massive reactors and processing plants that produced the radioactive element plutonium. The reservation is still off-limits to the general public, but you can visit the site on a couple of different tours- one which visits the site of the Manhattan B Reactor, the first large-scale nuclear reactor in the world and source of the plutonium in the bomb that flattened Nagasaki, and another which surveys the vast site in general and the ongoing efforts to clean up and remediate the pollution and waste left behind by a half-century of highly radioactive heavy industry. I signed up for both of these in March of this year, and in early June packed up the car and drove east from Portland with my partner, Erica Thomas, into the browning high-desert landscape beyond the Cascades.

Why visit this place? Because it’s possible, and because it offers a rare insight into a part of history that knit together much of the world in a skein of terror and apocalyptic violence, as well as to hear the story of how the work was done, who did it, and what it was done with. All that power and madness was made possible by the technical manipulation of a variety of rocks- uranium ores- and 75% of those rocks came from a single mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Additional supplies were sourced in Canada and from the Navajo Reservation in Arizona, but the vast majority of the power and poison that made Hanford a node in the great wars of the Twentieth Century, and which raised up the precipice of utter annihilation that the nuclear nations came to, arrived in this vast treeless expanse from beneath the soil of what was once a village in Central Africa.

The drive was surprisingly short, and we set up camp in a county park full of migrant workers, eating some of the first greens from the home garden under the swooping forms of nightjars at dusk. The park was impossibly lush and well groomed, and all around it the desert browned deeply in the coming dark. There were unfamiliar flowers in the dusty scrubland beyond the park boundary, and meadowlarks singing a dwindling song.

At dawn we were up drinking coffee, but not before the entire campground had cleared out, leaving only cheap tents and tentative early birds. We drove into Richland, about ten miles across dry low hills toward the bluffs of the Columbia River, and pulled into a small and unassuming strip of stores and entered the one marked Manhattan B Reactor Tours. The B Reactor has recently been added to the national park system, along with two other sites related to US nuclear history; the Oak Ridge reactor complex in Tennessee, and the Los Alamos research facility in New Mexico. Thus we were greeted in the clean, newish building by Park Service docents in neat uniforms and ushered in to a room full of folding chairs for an introductory slideshow.

The presentation impressed on us that the work that was done here happened fast. After the approval of the Manhattan Project to build an atomic bomb, the process of engineering the means to create the weapon moved at a lightning speed, and with a totalizing state power that is unfamiliar to us now. After a pilot surveying the interior west for empty expanses had identified this region as suitably empty, and with access to the cold water of the Columbia and some train lines, the US government moved in and evicted several small towns composed of up to 1500 white settlers, and imported 50,000 workers who took the B reactor from bare dirt to an unprecedented production of plutonium in 11 months. The work was contracted to the DuPont company, who were initially reticent to take the bid after (according to the docents here) having experinced some blowback from their massive arms production during the first World War. To prove their moral bona fides and commitment to peacable industry, they agreed to build the infrastructure for the most powerful system of personnel annihilation in history for the token sum of $1. They finished construction so early that they only earned 67 cents, and apparently a local Kiwanis club chipped in the last 23 so they wouldn’t feel shorted. This sort of homespun pabulum glossed the whole narrative experience of this tour, coaxing moments of aw-shucks can-do American spirit from the overarching themes of global thermonuclear war. The docents noted that at least 30 indigenous nations had used the landscape prior to their eviction by settlers and the subsequent mutilation of the atom by the whites, with 6 maintaining permanent or seasonal residence: the Umatilla, Walla Walla, Cayuse, Colville, Yakima, Wanapum and Nez Perce.

We loaded onto a bus and rode north. The highway skirts the reservation which is enveloped by the lands of the Hanford Reach National Monument, bordered on the northeast by the enormous tawny flank of Rattlesnake Mountain, a smooth fingernail of stone and soil. The ground cover was cheatgrass, almost exclusively- small hummocks of sagebrush appeared here and there on the taupe expanse but most every surface bore the early-brown nutritionless and tiny seedheads of this exotic plant that has been colonising the Great Basin lands of the interior west for almost as long as the whites have. Its name comes from its propensity to green-up, fruit, and dry early, hogging water and soil from native plants and presenting poor forage for grazing animals later in the season. It is also extremely prone to fire, burning hot and quick to make soils it inhabits unhospitable for much but more of the same.

The bus pulled off the highway to descend a low rise and off to the northeast loomed the hulk of B Reactor, a tetris-shape of angular forms abutting an enormous chimney. The entombed ruin of C reactor squatted just to the south. We pulled up into the gravel lot and filed out of the bus into the main reactor building, past a plaque marking this as the site of the first major nuclear reactor ever built.

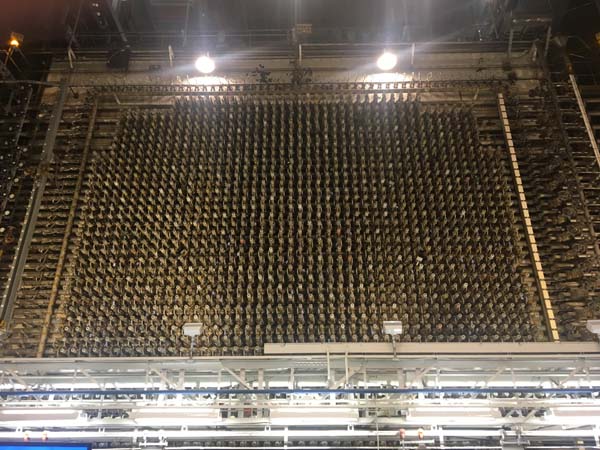

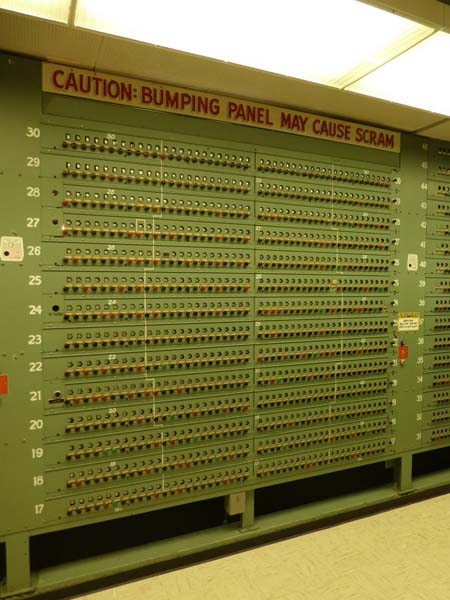

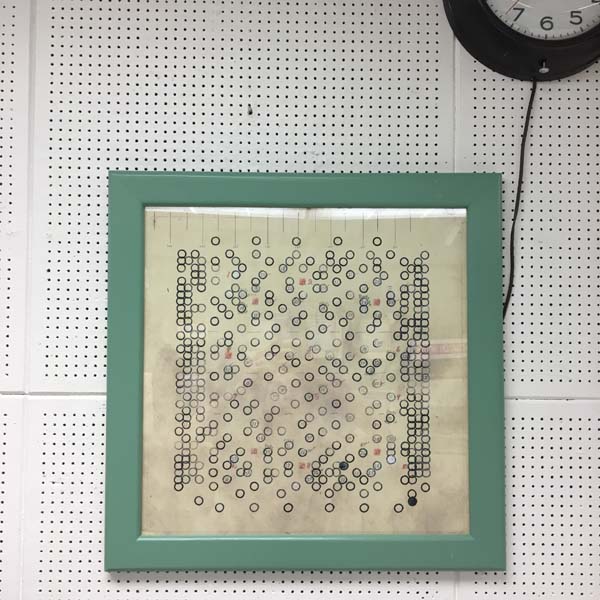

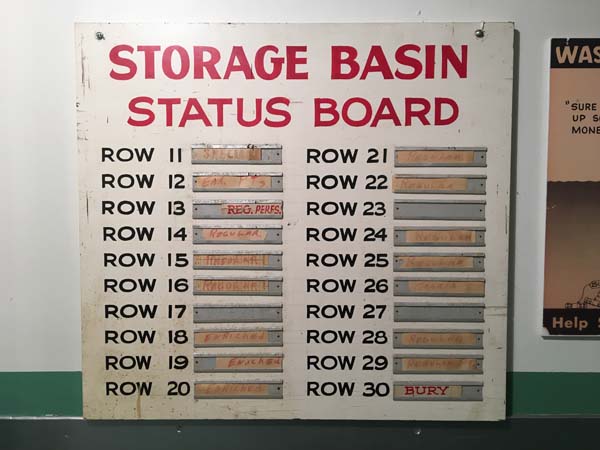

The face of a fission reactor is a bewildering mass of components writhing over each other in a complex symmetry. It is huge and imposing, and it also has an intimate quality like a jigsaw puzzle, giving the sense of having been assembled painstakingly by hand. A fission reactor of the sort represented by Manhattan B is also an astonishingly mechanical object. The reactor is composed of a mound of precisely machined graphite blocks drilled through with a series of holes, each capped and linked to a cooling system that flushes the interior with water. Into the holes are inserted aluminum-coated uranium slugs, which pass from front to back and are in the process enriched by a nuclear fission reaction into a form of uranium from which plutonium can be refined. The process is controlled by the insertion of vertical rods made of boron-enriched steel into the reactor- the boron absorbs neutrons and slows the reaction process, so pushing in or pulling out the rods modulates the rate of reaction. Emergency mechanisms to prevent runaway reactions include a system of enormous hoppers filled with boron-steel balls that could be released to cascade throughout the holes and tubes of the reactor. The room that holds this mass is like an aircraft hangar, supervised by a large American flag. The guts of the machine lie behind the complex face that we sat down in front of to listen to the docent, hiding the enormous room full of water into which the enriched fuel rods tumble and splash after their passage through the core.

B reactor produced its first enriched uranium fuel in September of 1944, made from refined uranium ore that came from the Shinkolobwe mine in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo. The nearby D and F reactors came online soon after and other reactors were developed in following years. The project was totally shuttered in the 80’s after producing a total of 64 tons of plutonium. It takes one ton of uranium to produce a half-pound of plutonium, which means that during the life of these reactors they consumed 256 million pounds of refined uranium ore.

We wandered the facility for an hour, taking in the displays of period infrastructure and signage, noting that the plant was a proud union-staffed facility. While staring into the locked chamber where the fuel rods had once cooled, an older man with a surprising mustache came up behind us and muttered “yeah they were going to open that up for the tour groups last year so you could walk out on those wood platforms and see how they used to fish up the rods from the water but it’s still too hot to let people go in.”

We returned in the early afternoon to the campground and walked over the sand hills to the river. Wooden tribal fishing platforms extended out from the concrete abutments of a small dam with water spilling over it in a smooth half-arc. In the eddy at the base of the fall a row of enormous white pelicans bobbed placidly in the foam. We walked upstream to the shade of a small catalpa and waded out to where the sun hit the surface of the water to swim and watch the evening swallows skimming the insects from the surface of the water. In the evening the campground was full of groups of men barbecuing, and the nightjars returned as well to dip and whine.

Next installment: the central sacrifice zone and the cleanup operation underway.

Interesting. I first got to go there in the early 70s. My grade school in Walla Walla Wa took our class thier.

This is amazing, a piece of history being collected