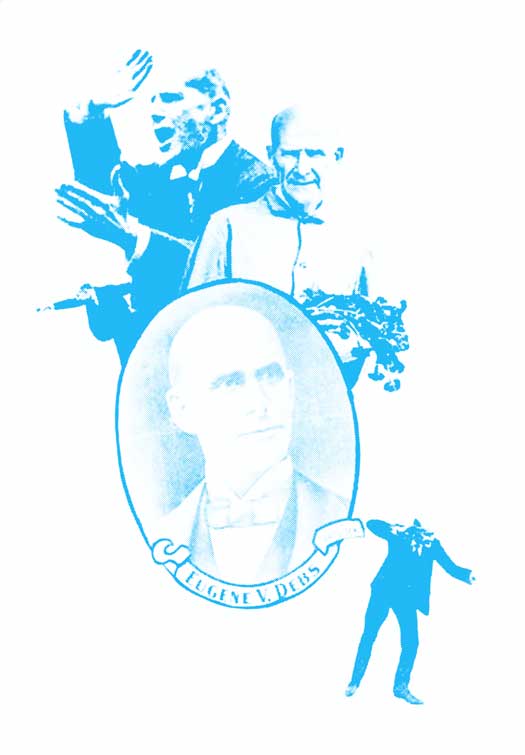

A critical view on monuments and whose history is presented and whose is omitted is crucial in the aftermath of Charlotteville. Here is a link to a PDF of an essay that I wrote on the struggle over public memory as public space as it relates to the Haymarket Tragedy. The essay has appeared in Realizing the Impossible: Art Against Authority (edited by Josh MacPhee and Erik Reuland, AK Press, 2007) and the book that I authored A People’s Art History of the United States: 250 Years of Activist Art and Artists Working in Social Justice Movements (Nicolas Lampert, The New Press, 2013) The introductory paragraph leads to a link to the full PDF.

Haymarket: An Embattled History of Static Monuments and Public Interventions

On May 4, 1927, a Chicago streetcar driver rumbled down Randolph Street. The driver had routinely passed by the Police Monument, the daunting statue of a policeman that commemorated the 1886 Haymarket Riot solely from the perspective of the police. The monument had originally stood in Haymarket Square, the site of the riot, but due to congested traffic, the city moved it to Union Park, between Randolph and Ogden. Its new location did not calm the discontent that much of the city, with a strong working-class identity, felt toward the statue. It had been vandalized before, but this anger was about to be taken to a new level. Veering from his normal route, the driver suddenly jumped the tracks and directed his streetcar full speed ahead into the base of the monument, knocking the statue to the ground. The driver, whose name is only referenced in historical accounts as O’Neil, gave a simple reason: he was sick of seeing that policeman with his arm raised.

In 1927, the memory of Haymarket still registered with much of the U.S. public, yet as the decades passed, it had begun to fade, even within Chicago. The distance of time, the failure of schools to teach its history, and a concerted effort by the city of Chicago and the federal government to erase its presence from public space all added to the steady disappearance of the memory, with consequences for future generations — primarily keeping the public uninformed about its own labor history.