To check out the website for this project, click HERE.

My grammar school used pesticides on the dandelions in our school field every year to beautify the grass. At recess we were not allowed near the field, so that we wouldn’t make wishes on their seeds and thwart the extermination attempts. It never worked. We’d play in the poison covered field after school, pick poison covered dandelions and blow their seeds all around. They couldn’t have exterminated them anyway; dandelions are a hearty plant that seeds easily and grows everywhere. Though the average person doesn’t know how to use them as a medicine or food, every babysitter until the end of time will show kids the fun in making wishes on them, and every kid is going to keep passing that on.

For many who will never need an abortion, for those with knowledge or preference for herbal abortions, or for people having other out-of-hospital abortion methods, whether abortion is legal or illegal might feel irrelevant. For those in cities where everything is easy to find regardless of legality it might seem like a distant and sensationalized argument. People have been performing abortions for thousands of years and legal or not, they always will. Anything legal can be manipulated by adjacent laws and controlled by money. So why does it matter? Because making abortion illegal doesn’t help anyone, it only makes lives hard. When abortion is illegal it doesn’t end unwanted pregnancy, it results in unskilled people performing them without health standards. To make abortion illegal when the procedure can help people is a sign of severe disrespect. As things are now, it seems more appropriate to say abortion is ‘not illegal’ than it is to call it ‘legal.’

Popular opinion assumes that people of the past were rigid, primarily concerned with being morally upright, and prone to damning someone’s entire character at the slightest infraction. We think they must have viewed something as controversial as abortion in harsh terms. It is falsely assumed that morals stemming from religion and stuffy old world customs were why abortion became illegal to begin with, or that abortion was just illegal forever until the 1970s. Plants, devices, and preventative techniques have always been used to regulate pregnancy. There is evidence of this in texts from many ancient cultures including Egypt, Greece, and Rome. There have always been knowledgeable practitioners to assist. In times of persecution information was passed on in coded language. There have been public killings, shaming, prohibitive laws, and guilt media. But though all these centuries and despite these tactics, the knowledge is still here. Abortion continues because it is important.

Though abortion is currently more affordable, reliable, and safer than it was before Roe v Wade, it is actually less accessible because of laws limiting abortion information and access. One example was just passed on June 19, 2012 in Arizona. The Senate passed a bill that prohibits parents from filing medical malpractice lawsuits against doctors who withhold health information if they believe that knowledge would influence the patients to seek an abortion! The last 40 years in the United States have also marked an extreme culture shift which was deliberately engineered by the anti-abortion movement. While a vast majority of people in the early 1970’s thought abortion should be legal and that it was nobody’s business but the woman’s, now more than 90% of the counties in the nation do not even have abortion services.

Recently I had the pleasure of interviewing Judith Arcana who has written about abortion, motherhood, and teaching. She was involved with the notable pre-Roe v Wade, women run abortion service in Chicago called “The Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation,” nowadays referred to as “The Service” or “Jane.” For more history and personal accounts on that project read Jane Zine: Documents from Chicago’s Clandestine Abortion Service, The Story of Jane or other documents.

From 1969-1973 The Service performed nearly 11,000 safe abortions. This was at a time when abortions were generally performed by men who were not doctors, often working for the mafia. Their interest was not in the well being of women but to make as much money as possible. It was common for a woman’s experience to be terrifying and dehumanizing, which sometimes included sexual assault. To protect the abortionist’s identity many women were taken to an anonymous location and were made to wear a blindfold throughout the procedure. Although unwanted pregnancy came with issues then as it does now, the problem most often expressed for patients at The Service was not shame or self-hatred, but money. Judith Arcana explains, “Most abortionists wanted $500-$1,000 or $2000, and listen, honey, we are talking 1970 dollars. So think about some 16 year old, some 20 year old college student, or some 25 year old who’s already got 3 kids and her husband’s a truck driver. $1,000 in 1970? Not possible.” Other underground services existed including a pregnancy testing service and a network of various religious leaders who recommended abortionists around the country. However, The Service was unique. Jane became the only service available of its kind in the US run completely by women and offering counseling services before and after the procedure. Abortions were priced at $100 or whatever the patient could afford, and also offered no-interest loans. The Service operated until the success of Roe v Wade when they disbanded so as to not be practicing medicine without a license. I spoke with Judith about the culture and work that Jane provided. Here are some stories from our talk.

“When you’re working with somebody – in the Service- your thinking is: this woman has decided to have an abortion and you’re going to help her get it because you have the connections and the skill to do that. The fact that she voted for somebody different than you did, or she goes to a Church every Sunday that tells her that she shouldn’t have an abortion and she’s doing it anyway – that is not what’s at issue. For Janes, the goal was to be good to the women, work with them to help them get what they needed and follow up after the procedure. One of the things we learned is how to be supportive and useful even in an alliance between people with different world views, which is an extremely useful skill in itself.

So many different kinds of women came to the service, because one of the things that almost all women are capable of is conceiving. Regardless of whether a woman is heterosexual, partnered, or desires to have sex, most are capable of becoming pregnant. While in the Service, I encountered people I would not have met otherwise. I was grateful then and I’m grateful still for the opportunity to work with people who were teaching me even though that’s not what their goal was when they called me or showed up. The Service changed the way I thought about being a person and a woman. It even changed the way I thought about being a person and a woman. It even changed the way I thought about being a mother and a teacher. It changed everything that was really important to me because of how deep it was to be doing this major league work.”

Judith tells the story of a father who brought his daughter through the Service.

“This is a perfect example of how the emotional content of that anger would be relatively different today, given the success of the anti-abortion movement. He thought (in 1970’s terms) that she messed up, and he was angry at her. Of course he was probably also burned that his daughter was having sex. She was not a teenager but she was young, and so he was totally dragged. He was also clearly someone for whom $100 was no big deal. I remember that he literally gave her a $100 bill. There were people who came to us with handkerchiefs knotted around change. He and his daughter were people for whom the money was not the problem. He was a good example of one way of looking at a young woman’s sexuality in that time: ‘she had an accident.’ People used phrases in those days such as ‘she got caught,’ or ‘she got herself in trouble,’ or ‘some guy got her in trouble.’ These were ordinary expressions of the time and I’m sure he was thinking in those terms. It’s interesting now to think about the fact that he didn’t say, ‘I’m not helping you.’ He didn’t say, ‘You are a bad person.’ He didn’t say, ‘You are a sinner.’ He didn’t say, ‘You have to have this baby.’ He knew abortion was the right thing to do even though he thought what she’d already done was a bad thing. He came with her and he paid for it and didn’t say to her, ‘You have to earn that money,’ or ‘You have to give up your stereo.’ Many women sold their stuff to afford an abortion- that’s still true even now. That aspect may be worse now because it’s so much more expensive than the Service was. There is no underground service and abortion costs a chunk of money and not a lot of people have $300, $400, $500 (or more) to easily spend. So women sold their stuff, some turned tricks. Women have always done what needs to be done to get the money to do what they need to do. But that dad, he covered it even though he was pissed off- which was an amazing thing.”

“People would say things like, ‘My husband doesn’t want me to do this; he doesn’t know I’m here.’ Or, ‘My boyfriend won’t help me pay.’ Or, ‘I can’t let my family know about this, they would think I was bad for having had sex.’ That was more common than personal guilt feelings. They would talk about whatever it was that was trouble for them, but they did not talk about it in the way that women talk about it now.”

“In the year 2000, twenty five years after the anti-abortion movement had taken over the minds and the emotions of the American population, I visited a clinic here in Portland Oregon. I was working on my book of poems and monologues that was published in 2005 called What if your Mother. I thought I should see how people experience abortion in a legal clinic- under duress, possibly with protesters outside. I visited and talked to a variety of people. The clinic workers would say to the women, ‘There’s a researcher here doing some work, is it alright with you if she joins us?’ I think everybody said yes and I was there the whole afternoon for about a half dozen abortions. I realize this is not what you would call scientific sampling: but all but one of the women I talked to expressed feelings which were far more negative than the women I talked to in The Service when we were working underground. This is a clinic where everybody’s wearing scrubs and they can even use drugs to put them to sleep. They’ve got everything, state of the art! These women were filled, and this is the important thing, filled, with shame and guilt. Several of them said they hadn’t told anybody they were going through this experience. It was so shocking to me that at one point I almost had to leave the room because I thought, ‘Oh my god I’m going to start to cry right here.’ I really had to get a grip on myself because I wasn’t expecting it.”

“Being in the room, talking with them and holding their hands the way that we did in The Service and hearing them speak of themselves in this dreadful way really hit me on a visceral level- the terrible damage done by the anti-abortion movement over these past several decades. A women having an abortion considering herself a murderer would have been unheard of in those years (1968 – 1973). Nobody thought such a thing. They were sometimes unhappy or frightened, but they never thought themselves murderers. Where there was shame, it was shame about having sex, or shame about having messed up- not shame about having an abortion!”

“After the Roe decision, some women became part of a group that started a free people’s clinic called the Emma Goldman Women’s Health Center in Chicago, which lasted at least half a dozen years and then morphed into the Chicago Women’s Health Center, which still exists. That place was essentially founded by a group that included some Janes and is quite wonderful. These people have even trained themselves to be able to deal with patients who are transgendered folks, and they are seriously committed to doing healthcare in the true meaning of the word ‘care.’ Over time the project morphed as people grew more politically and emotionally needful of straight arrow legal work. In the 1970’s, you could have a community clinic staffed by people who were not MDs. But by the 1980’s people would be afraid. Of course the Jane folks had a very different feeling about what healthcare and even medicine could be. Some Janes became nurses, and I knew of one going to medical school after she was done with her Jane work.”

“Decades ago Bernice Johnson Reagon wrote something like this: If you’re working in an alliance across serious identity and political differences and it feels good, it’s not succeeding. When I read that I thought, yeah, that’s right. Because if you’re comfortable that means you’re not addressing the differences among the people struggling to create an alliance. The goal of the Service was not “political” in the sense that we weren’t working together to create a movement. When women showed up we were working together to get an abortion, which is of course a very political thing to do, but the goal is that one relatively simple action, and that was one of the things about Janework that was very satisfying. We were not theoretical or academic in the practice.”

“There was a long time when I was busy with other things and didn’t think about abortion every day the way as I did when I was ‘Janeing,’ (as we used to say). But in 1998 I started to write about The Service in poems, monologues and stories. I did that research I mentioned, and now I’m back on the case in a way- as a writer, rather than as an operator, so to speak. At some point in the not too distant future I’m pretty sure abortion will be illegal again- in fact, though technically legal now, it’s widely unavailable already- so I think we have to do the necessary work.”

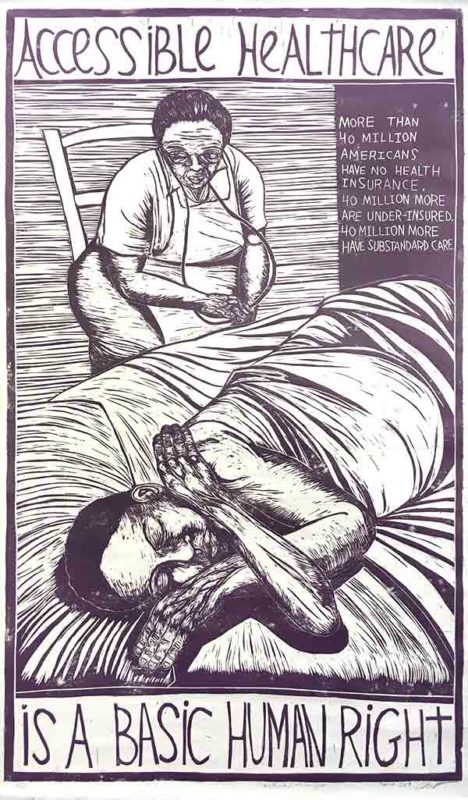

For me, one strangely comforting reminder in that growing possibility is that the mainstream medical industry is not concerned with helping women or healing patients. It’s to make as much money as possible. As the anti-abortion movement has succeeded in shifting the feelings around abortions, the medical industry has done an excellent job of pushing time tested medical practices out of consideration. Most treatment is literally unaffordable without health insurance, and insurance itself is often prohibitively expensive without a certain kind of employment. Prescribed medicines are constantly changing, one medicine to counter the side effects of another. Even commonly prescribed drugs have addictive properties, and many of these expensive treatments are not cure-oriented but only meant to suppress a particular symptom, and only for the duration of the dose. Herbal and other methods that are impossible to patent are ridiculed or intentionally not researched. The notion of useful alternatives is considered laughable, immature, or up for debate rather than a collection of honed, proven and practical techniques.

The result is that many people in the United States feel disempowered and incapable of controlling their own health while dependent on a fickle system that views each person as a dollar sign. Laws are passed that reject medical/scientific data and don’t put patient care first. Despite the monopoly the mainstream healthcare industry has on treatment for even the simplest ailments, most people feel wary and extremely skeptical about looking elsewhere.

Dandelions were brought here from Europe because they were considered impossible to live without. They were called a cure-all, edible and medicinal, every part useful. Today, practices like midwifery, apothecary, acupuncture and any medical techniques conducted independently are considered quackery suited for wealthy eccentrics or impractical hippies with fringe interests; not accepted by the general population. But if abortion becomes illegal, the ones who depend on hospitals and aren’t wealthy or connected enough to access abortion will be the ones hit hardest and will be looking for alternative choices.

It’s important to create a culture in which people feel capable of making the decision that’s right for them, and have enough trust in themselves to see it through. We can be prepared and empowered by educating ourselves about maintaining our bodies ourselves. Educating, healing and teaching one another bonds people in a way laws cannot nullify. What people learn from one another when they offer themselves with openness becomes permanent and huge, informing the being of a person rather than establishing some rule that can be rescinded. Amidst that kind of growth restrictive, harmful laws become small.

Judith also told me this: “Several years ago I was talking with one of my dearest friends who was also a Jane. I said something about being a Jane in the past tense and she said to me, ‘No past tense- once a Jane, always a Jane.’ She’s right, this is part of who I am and that will always be true. Given the politics and misery of what I call the horror show of the anti-abortion movement’s success in these times, it’s not possible to deal in past tense, really. When you win one of the battles in a struggle for radical change in society you can be -of course you should be- happy, even jubilant that you’ve been able to prevail to make the forces of good move ahead. However, you can never think it’s over now, and you’ve won.”

And in the meantime the dandelions will continue to travel, grow, wait, as plants can. Dodging pesticides, enticing new messengers to spread their seeds, until, perhaps, we find a use for them again.

-Sam Merritt