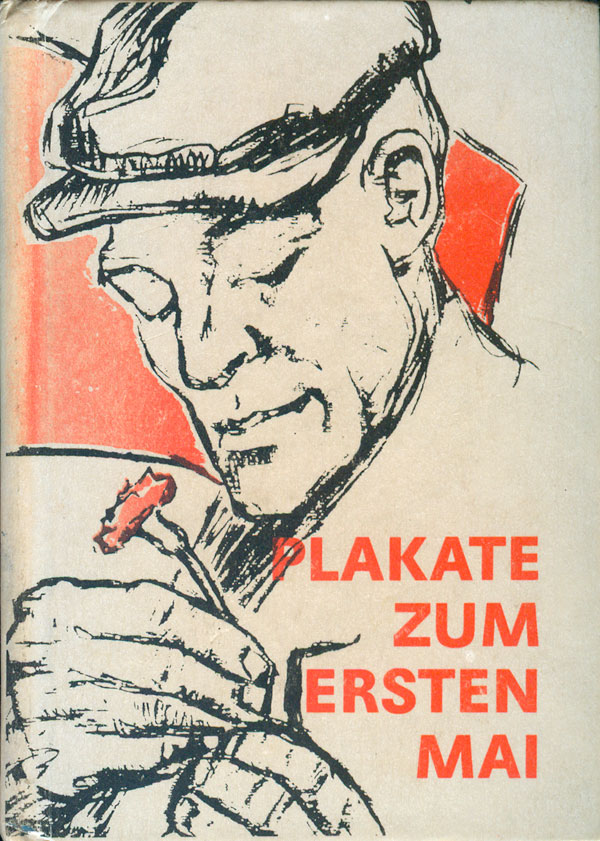

This week is the final in a series of posts about mini-East German poster books (see HERE and HERE). This week’s book, Plakate zum Ersten Mai (Posters for May Day) was quite literaly one of the last gasps of the DDR, published in November 1989, after the Berlin Wall had already started coming down. The book is about an inch wider and taller than the other two, but is still considerably smaller than most other books—about half the size of a mass market paperback. It’s also put out by a different publisher, Verlag Tribüne Berlin, and has an ISBN number.

I’m unsure of the history, but Tribüne Berlin was the name of the main political/expressionist theatre in Berlin beginning in 1920, and was a popular hang out for Dadaists like George Grösz and John Heartfield. It’s possible that this little book was produced by the publishing wing of the theatre. Unlike the other books, this one is only in German, so it’s a bit harder to suss out.

The full title of the book is Plakate zum Ersten Mai aus der Geshichte der Arbeiterbewegung (May Day Posters from the History of the Labor Movement), with posters from six Eastern Bloc countries: Bulgaria, Czecholslovakia, East Germany, Poland, the Soviet Union, and Hungary. The book contains 169 posters produced over almost one hundred years, 1890-1988. It’s an impressive collection.

The cover is quite strange. It’s a detail of a 1946 German poster by Arno Mohr. It’s clear in the actual poster that it’s a rough drawing of a working class man putting a carnation through a buttonhole on his shirt on May Day, a big red flag waving behind him. But with the cropped image on the cover, the flag is gone, the red has turned to an almost neon pink, and the flower could just as easily be a little Vienna sausage on a cocktail fork. A sad out of work dude with nothing to eat but a mini hot dog. This, of course, hardly seems appropriate for the great workers’ holiday!

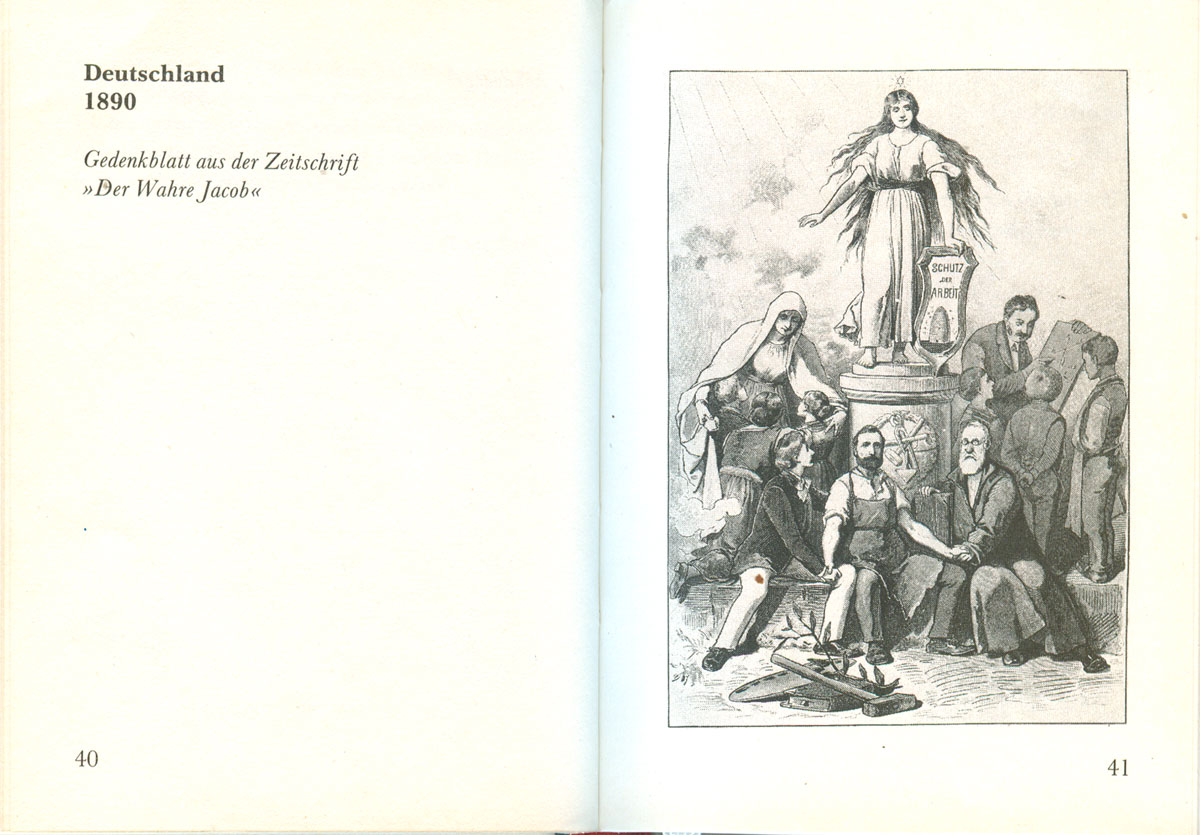

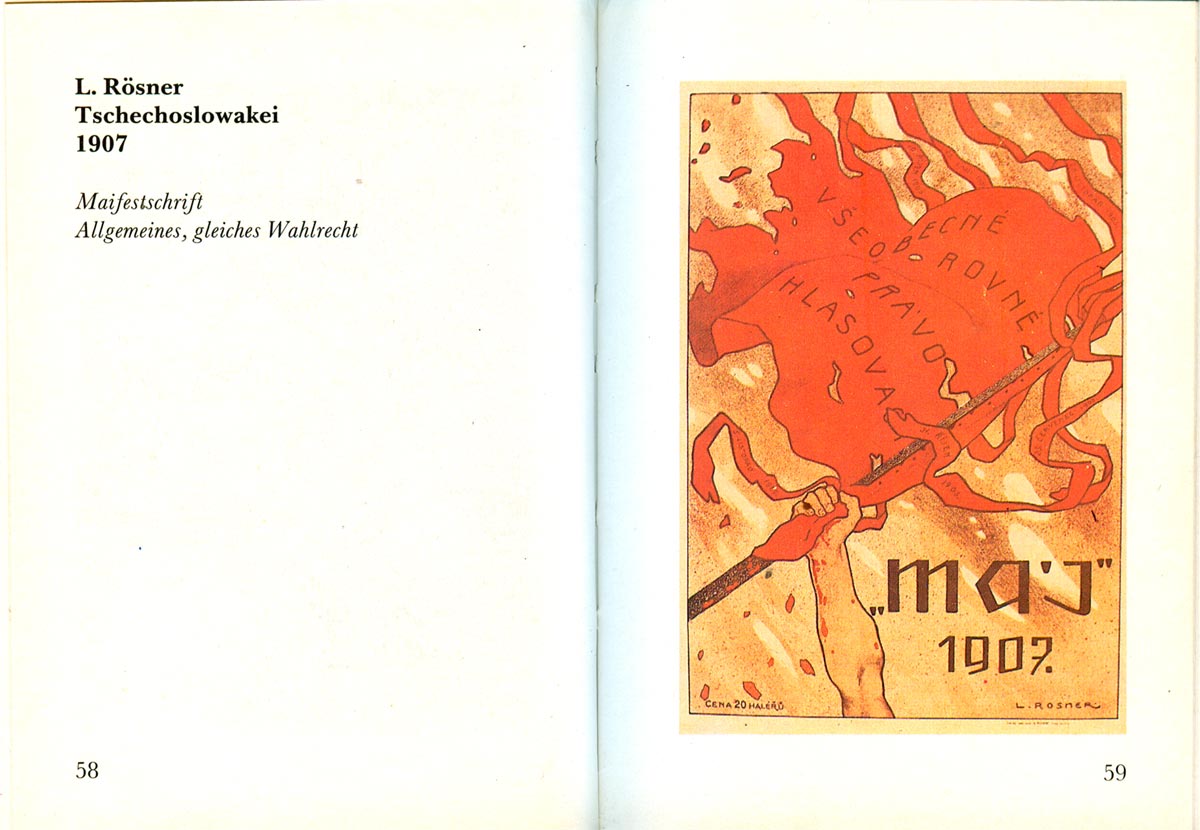

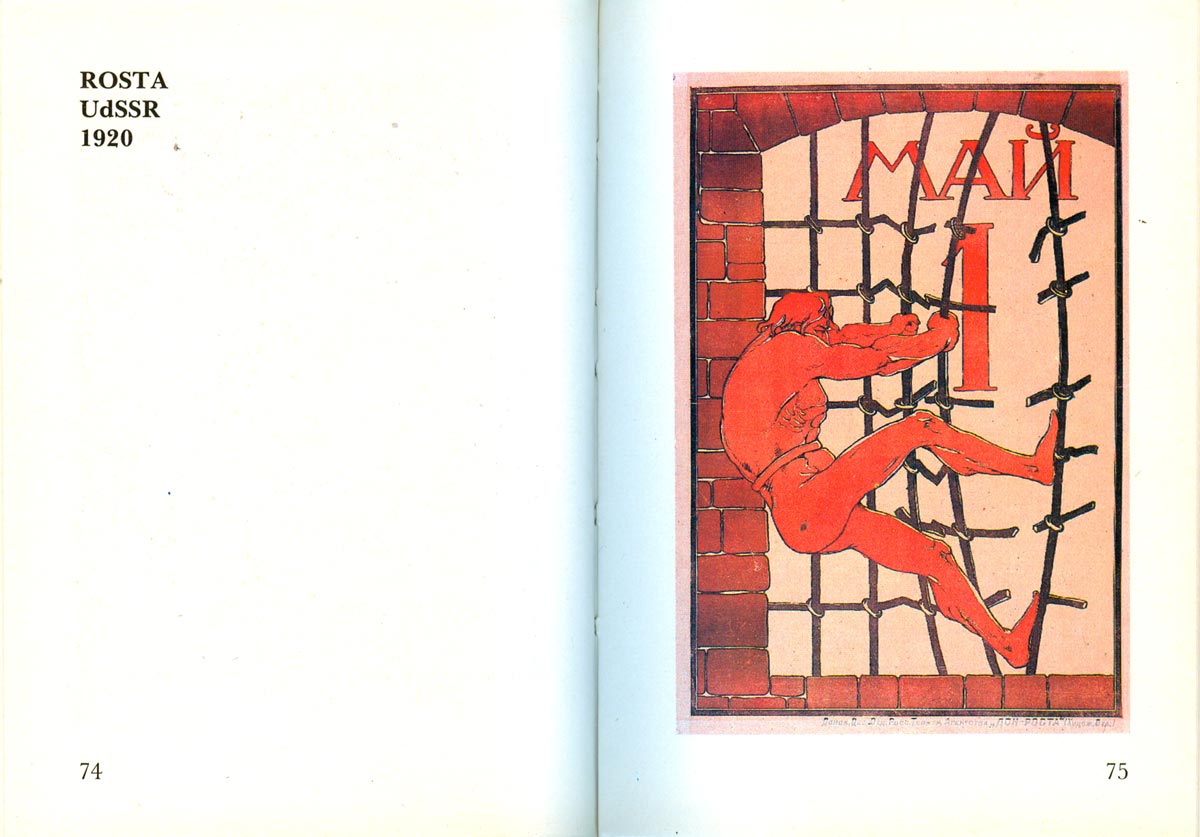

This book is designed much like the others, with poster image on the recto and credits on the verso. The artist is listed, then country, then date. The text on the poster is also translated into German if it is written in a different language. The book is chronological, with two or three posters from most years, excepting ten posters in 1920 from the Soviet Union alone, and a big gap during World War II.

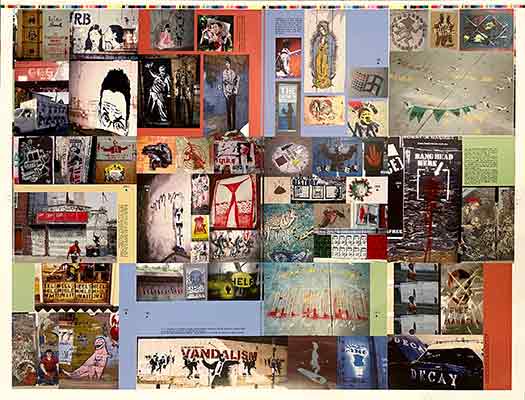

So many of these posters are just awash in red and flags. The symbolism is heavy-handed, but it’s not hard to see why it worked. There is a compelling emotionalism in many of these design.

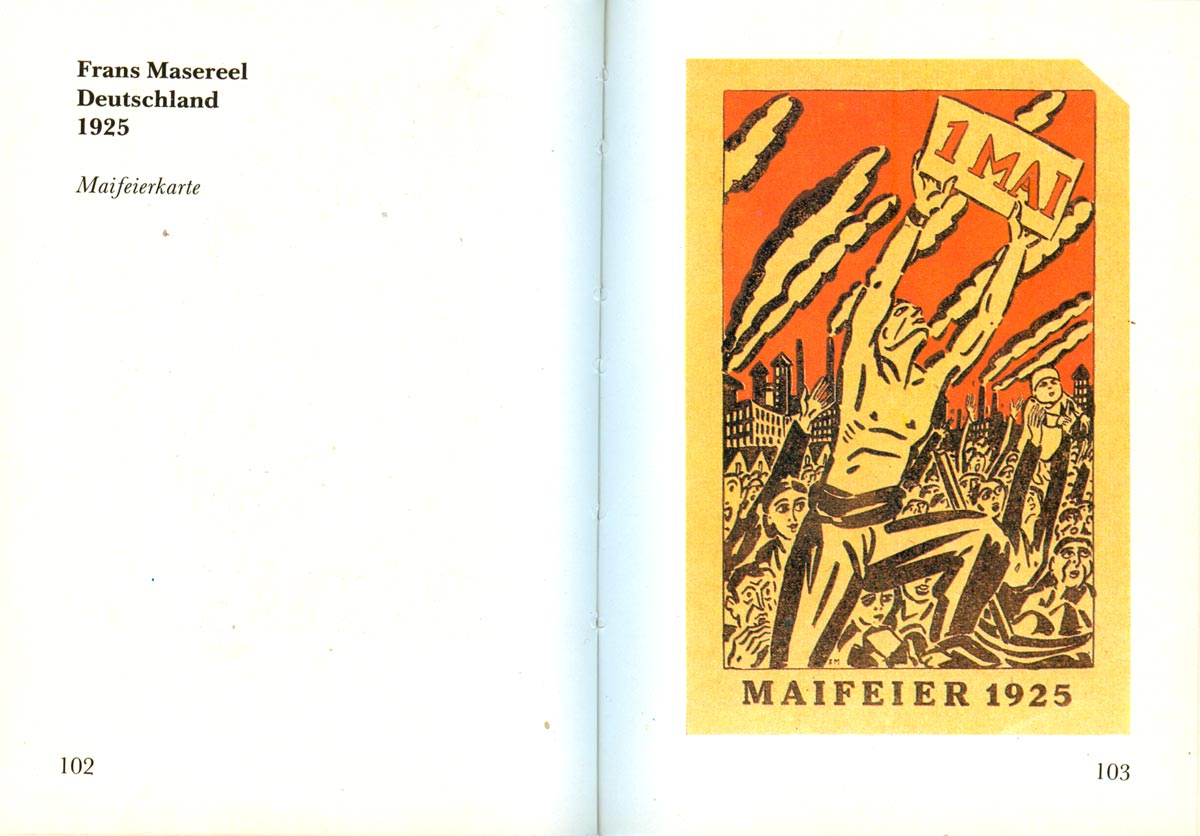

A rare poster by Frans Masereel, the father of the wordless novel.

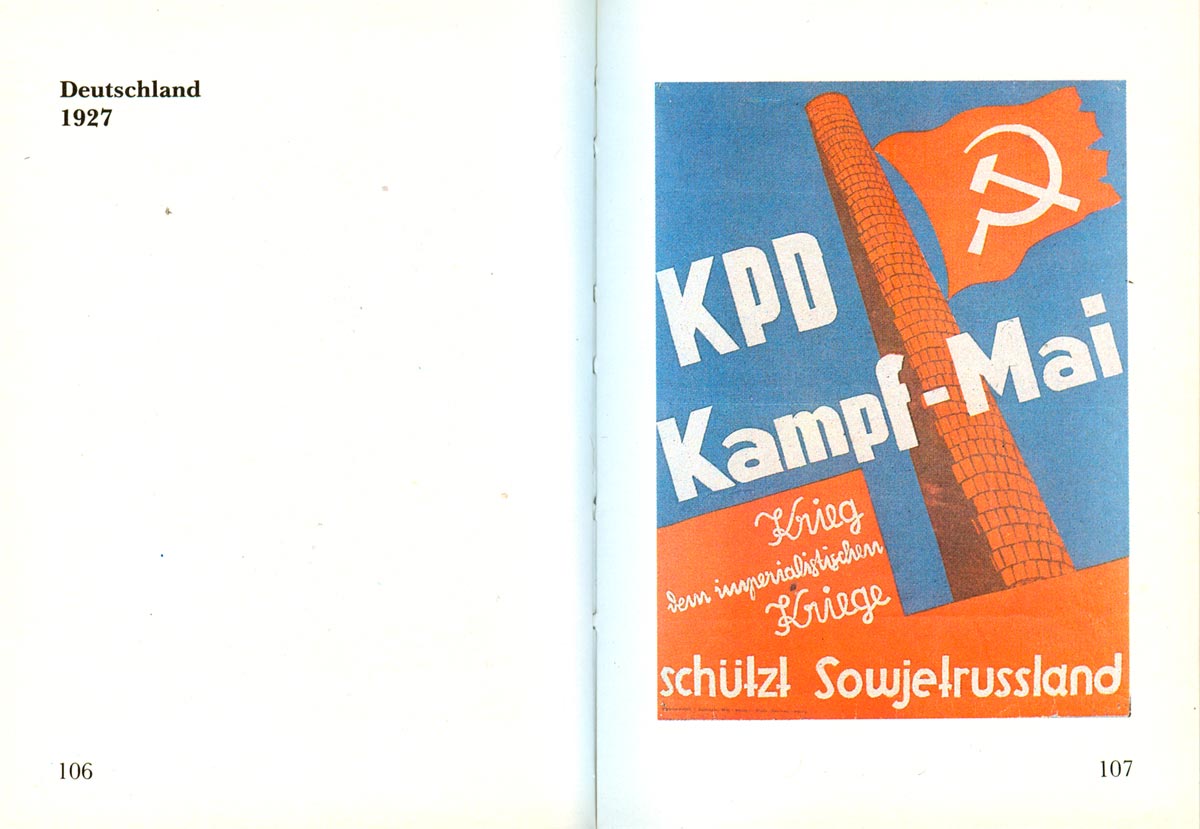

You just can’t go wrong with flags, smokestacks, and hand drawn type. Well, at least design-wise.

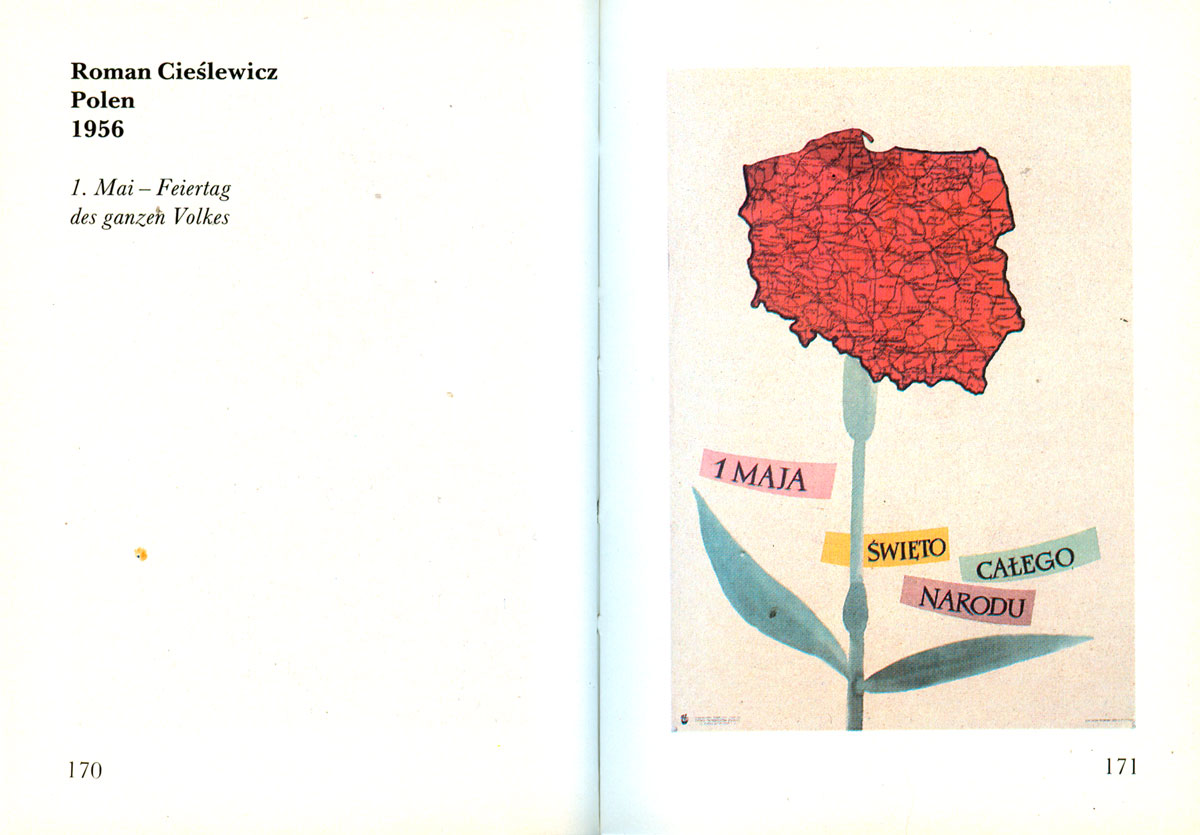

An early poster by Polish designer Roman Cieslewicz. The carnation returns here, taking the form of the map of Poland. The collage is jarring, with the stark red map carrying a different intensity than the lightly painted stem and banners. But it does appear to presage his later, much more powerful work. I featured Cieslewicz in the early days of the JBBTC blog, you can read those posts HERE.

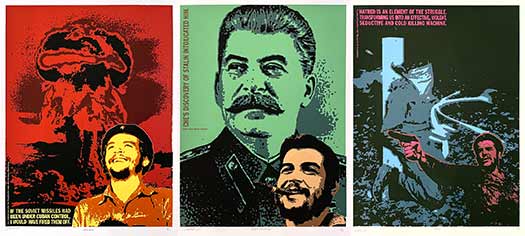

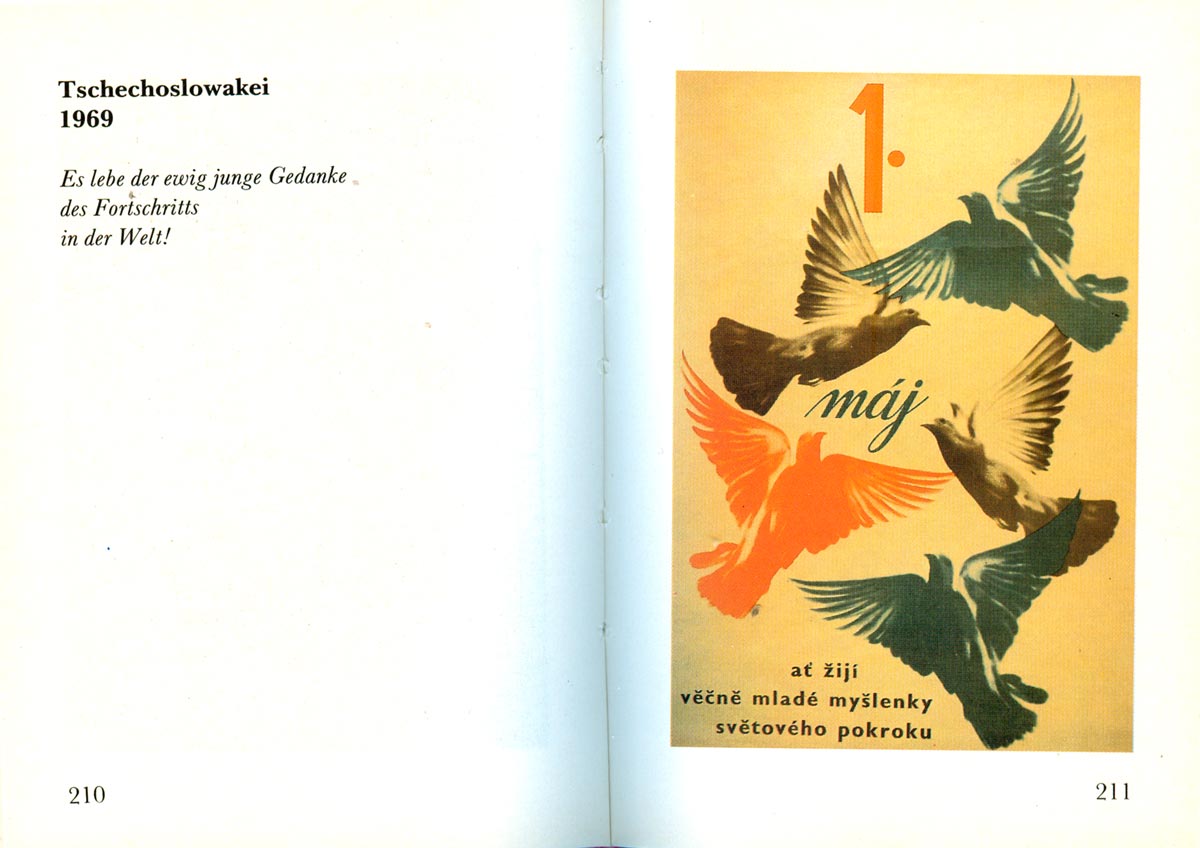

I wanted to show this example because I find it fascinating, and almost impossible to believe, that this is what was being produced for political posters in Czecholslovakia in 1969. While movements in the U.S., Western Europe, and even Cuba were absorbing the styles of pop art and increasingly eclectic commercial design for their posters, this is a straight throwback to the early 50s.

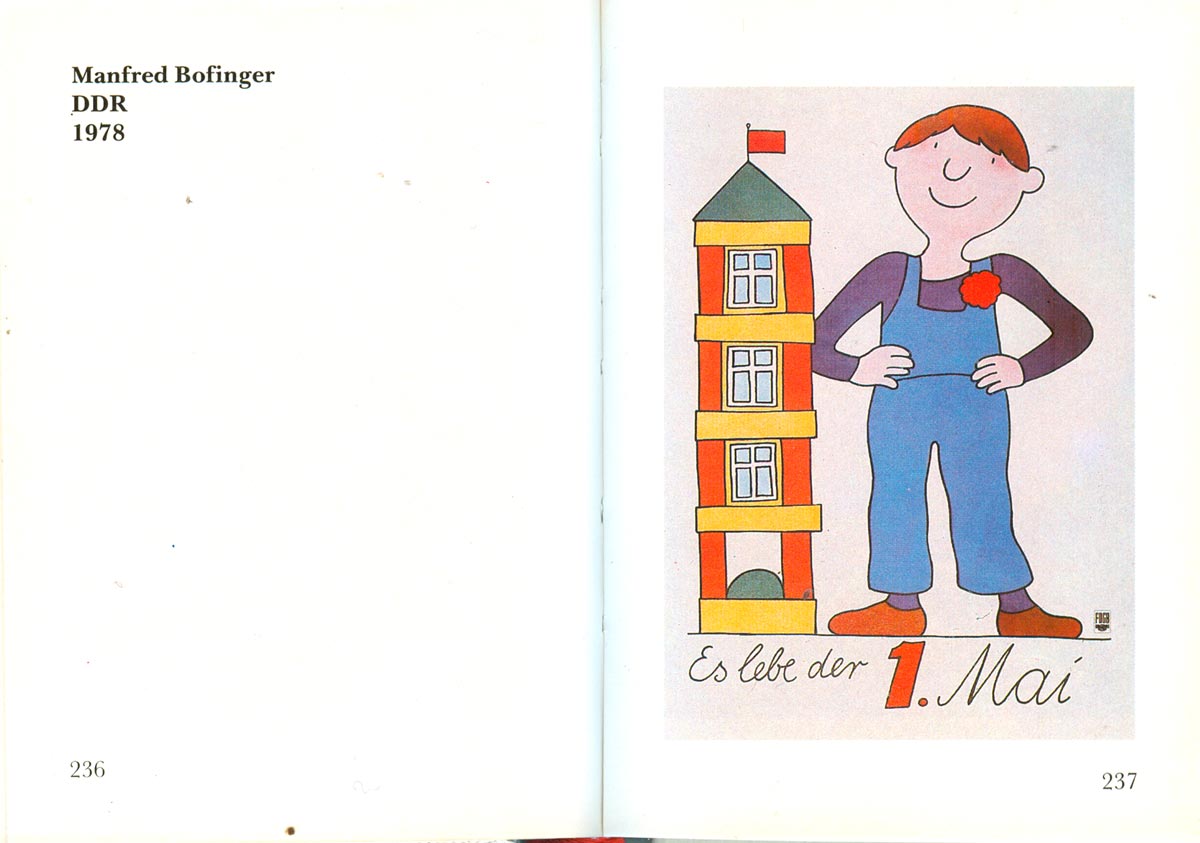

Ugh, another inscrutable example of East German design. May Day or advertisement for kindergarten?

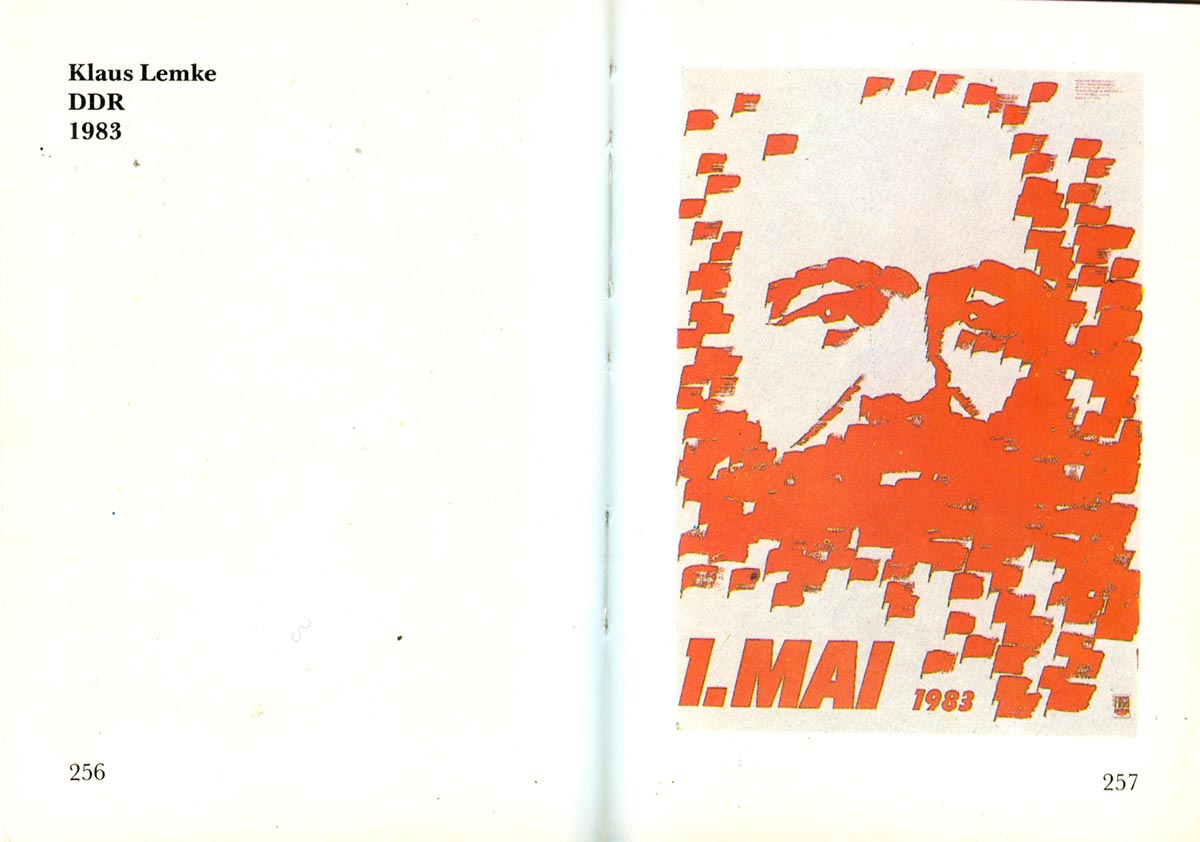

Red flags, flags, and more flags! Here a dozens of flags march together to merge into the visage of ol’ Papa Karl. North Korean choreographed events have got nothing on this East German poster, although the thought that the DDR state apparatus could mobilize this kind of support for Communism in 1983 is clearly wishful thinking.

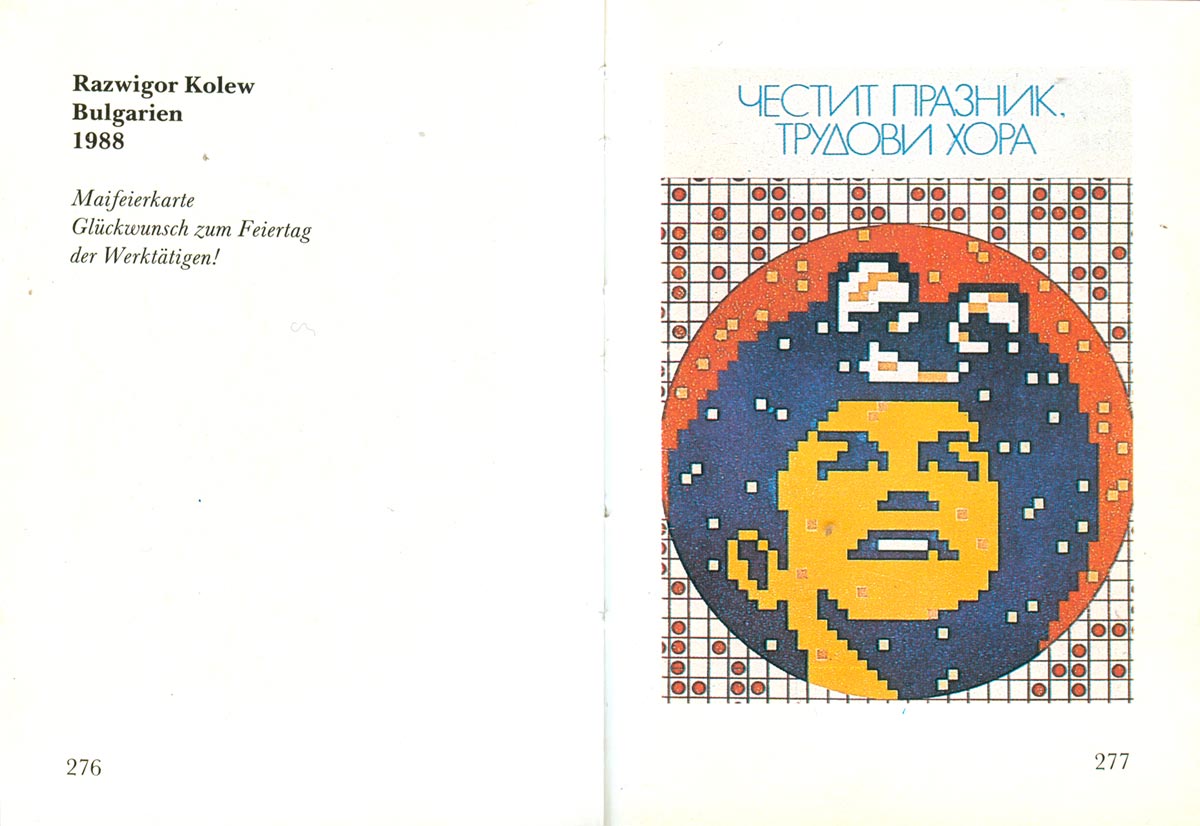

And finally, back to the future of the working class. I must admit a soft spot for 80s and 90s graphics that render images in pixels as a way to show progress or the future, since even then it already looked out of date!

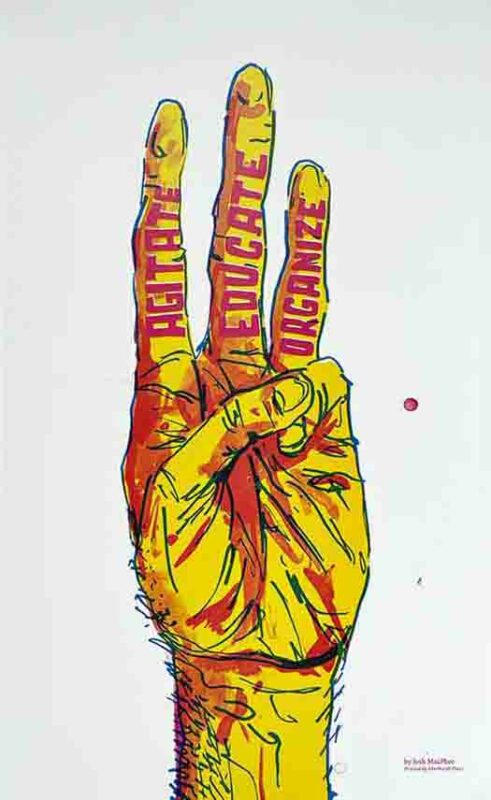

However silly some of the specific examples are, I’m still impressed with the sheer amount of effort mobilized to celebrate the birth of the labor movement and working people across the globe. I’m not naive, and know that in many of these contexts these posters likely functioned more as a bludgeon against the working class than a tool of liberation. But at the same time, now we exist in a context where not only is organized labor practically invisible, but the nature of labor itself has evolved to the point of often being unrecognizable. We work all the time, pumping our ideas and emotions onto social media and blogs like this one, without a thought about the fact that we are working. Working without a wage, or benefits, or safety net. Working for some sort of social recognition while the owners of the media platforms extract our clicks and likes into profit.