Lake-Effect, an exhibition at (scene) metrospace, is the first public event in an ongoing series of projects that interrogates the history, culture, and life of the Great Lakes. Lake-Effect is about the place I call home. It opens tonight in East Lansing, Michigan.

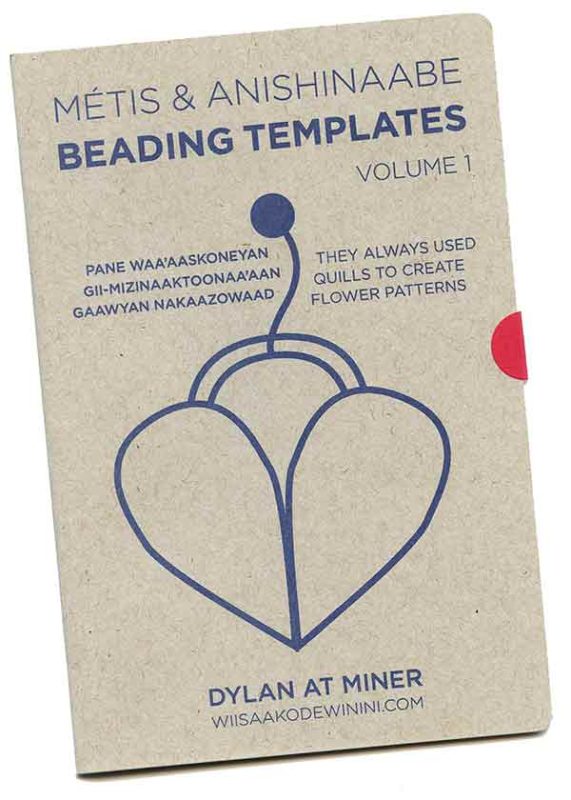

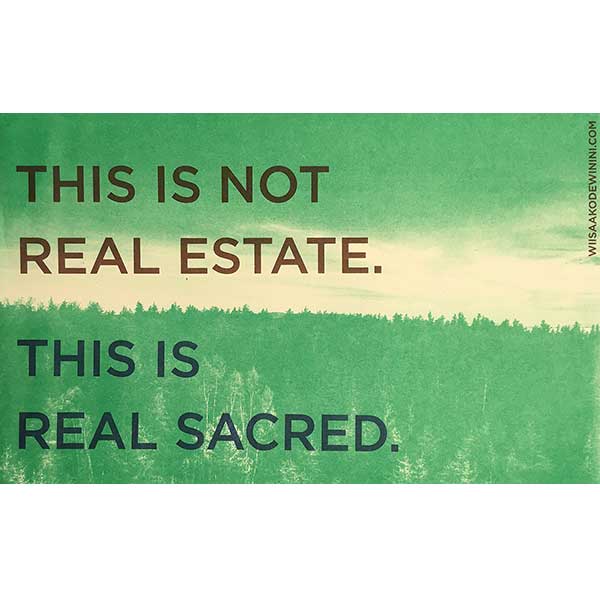

The project first emerged during my (very) marginal participation in initiatives, such as as the Midwest Radical Culture Corridor (MRCC) and its affiliated Compass Collaborators. In these and other projects, artists and cultural workers from across the Midwest began to investigate the Midwest and what it means to call this place home. As someone who explores regionalisms in my own artistic practice and scholarly writing, these initiatives resonated with me. I began to ask: what do the Great Lakes look like culturally? Like many in the region, especially my indigenous cousins, the lakes speak to me, as do the people and its spirits. This is a place that we should properly call Anishinaabewaki.

Beginning in 2005, critic Brian Holmes and artist Claire Pentecost, among others, investigated the notion of a continental drift, ‘an exploration in collective autodidacticism’, via a series of workshops at 16 Beaver in New York City. Since both Holmes and Pentecost live in Chicago, at least part of the year, they also employed the notion of a continental drift through the Midwest in 2008. As artist Sarah Kanouse (a participant in Lake-Effect) writes in a book on the drift: ‘from June 4 to 14, 2008, a group of people traveled through Illinois and Wisconsin in search of a Radical Midwest. Starting in Urbana, Illinois and winding our way through Chicago, Milwaukee, rural Wisconsin, and Madison, we visited places where alternate pasts and futures sprout up and grow roots in the stress-fractures of a society built on violence, exploitation, and environmental destruction.’ Drifting through a geography recognized as the ‘Radical Midwest’, participants dissected the particularities of place. In a similar vein, Lake-Effect is about this place, as well.

Accordingly, this project expands the issues commenced by other artists and activists, but re-conceptualizes this region toward one that uses the Great Lakes Watershed (although I take liberties with what fits into the watershed) as the primary way of relating to place. While, I have always seen Michigan as participating in the Midwest, I have never fully appreciated the way that the Great Lakes’ unique geography gets dismissed for the sake of simplicity. Michigan and Ontario have more in common than do Michigan and Nebraska. The US-Canada border is a fallacity, one built on settler-colonial boundaries.

Michigan, for instance, is a peninsula surrounded by freshwater. It has the longest coastline in the lower 48 states and the world’s longest freshwater shoreline. In addition to our close access to freshwater, the Great Lakes also shares a unique history, one that includes Indigenous and settler populations; urban and rural ecologies; industrial, agricultural, and undeveloped economies; old-growth forests and dunes; decrepit cities and forgotten villages, to name only a few of the binaries that exist in the region. Lake-Effect, as an ongoing project, will explore each of these issues, as well as many others, that are important for humans and their non-human relations in the Great Lakes.

Beginning in 1787 in the United States, the region surrounding the Great Lakes became known as The Northwest Territory and included what today are Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and parts of Minnesota. Thinking about the Great Lakes watershed lets us link these states with two Canadian provinces, Ontario and Quebec. If you follow the riverways that flow into the Great Lakes, as my ancestors did, you can travel to Lakes Winnipeg and Manitoba. So for the sake of this project, maybe we should also include Manitoba. The Great Lakes Cultural Watershed, as I call the networks that exist here, has a relationship with people and place that goes beyond what we can easily identify as the Midwest. The lakes are the center, becoming an epistemological axis mundi.

With this in mind, Lake-Effect returns to the importance of the lakes and the people who live around them. While this isn’t a project about water, per se, it is an ongoing investigation of what happens here. If you live here, you probably know that the project’s name, Lake-Effect, is taken from a particular form of precipitation that occurs around the lakes when winter storms accrue moisture over the lakes before dumping large snowfalls once they reach the shore. This is a unique meteorological phenomenon that occurs in a few places around the world. Western Michigan and the Upper Peninsula, and Buffalo, New York, in particular, are well-known for lake-effect snowfalls. I evoke the concept as a metaphor to explore and document existing artistic and cultural practices in the Great Lakes Cultural Watershed, before ‘precipitating’ that information in the form of exhibitions, publications, dialogues, and other projects.