Chinese Posters, Stefan R. Landsberger & Marien van der Heijden (Prestel, 2009)

Soviet Posters: The Sergo Grigorian Collection, Maria Lafont (Prestel, 2007)

North Korean Posters: The David Heather Collection, David Heather & Koen De Ceuster (Prestel, 2008)

Vietnam Posters: The David Heather Collection, David Heather & Sherry Buchanan (Prestel, 2009)

These are first and foremost picture books. Each one contains a basic introduction to the history of political and propaganda poster production in each country, but no more than a dozen pages of overview. This series is aimed at a general audience, appealing to the novelty of posters from “strange and totalitarian regimes.” That said, each one has its unique benefits and value, and for the most part these are worthwhile books for people interested in the production of culture under political regimes that in their prime attempted to challenge capitalist hegemony (for better or for worse).

In a state-run economy like China, where the state controls the means of information production, a poster can move from design to printed page in ten hours, creating near instantaneous mass distribution of printed propaganda supporting state policy. In the 1950s, when television had barely cracked the country, this was the direct lever of ideological control. On top of it all, many of the posters were actually sold, so the Chinese government created a self-financing propaganda machine! I would have liked to have seen more info about this (and more info can be found, esp. in Lincoln Cushing and Ann Tompkins’ Chinese Posters: Art from the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution).

OK, on to the Soviet Union. This book is surprisingly interesting, in large part because the curation is so haphazard. Rather than a cleanly manicured collection of the “‘best” constructivist and socialist realist posters from the 1920s through the 50s, pulled together by a art historian with a Soviet specialization, this is a somewhat random archive of posters collected by a former-Soviet businessman. This less groomed approach somewhat problematizes the simple and assumed version of Soviet aesthetic development with pre-modern/traditional image making (1910s-20s) giving way to constructivism (20s-30s) giving way to socialist realism (1930s-50s). It’s not so simple a progression, which this books shows clearly. Walter Crane-like craft style shows up in the late 30s, Toulouse-Lautrec-like film posters show up in the early 30s, 60’s-esque pop cartoons show up in the 50s, and constructivism is generally scarce. After the early 30s, there is certainly no full conversion to socialist realism, it’s a hodge podge of styles.

The Korean book is the least interesting to me. There is almost no information about how the posters were produced, and the posters are organized by theme instead of date, with little to no information about how, when or why the posters were produced. In general most of the posters appear to be rough copies of Chinese posters, with thick-armed, heroic workers, peasants, and soldiers. Without additional information, it’s hard to glean much insight from the images, and the book comes off like a sub-level version of the China book. There are some pretty fun and innovative representations of the evil USA, but they are in the minority.

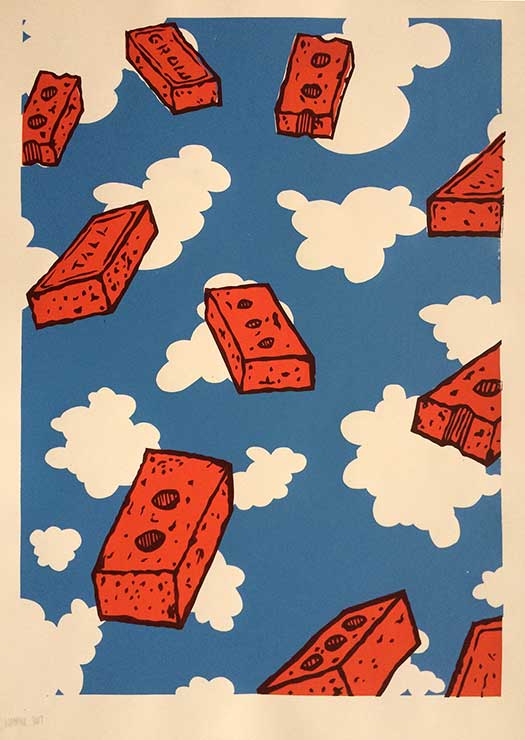

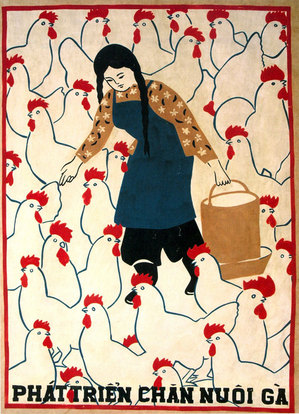

And finally, Vietnam. This is definitely the most interesting of the books, the real catch of the collection, because the material is less known and the styles more unique. The posters here are quite diverse, in part probably because they were produced under extremely varied conditions. Some were likely hand-painted during the heat of the Vietnam War, others are multi-color block prints, some are offset, some screen printed, and others are clearly contemporary digital inkjet prints, but it is unclear if the book is reprinting digital reprints of originals, or if they are current pieces made to look like they are from the 1970s. Here is where the best and worst aspects of this book serious crash into each other, we are presented with an explosion of fascinating images, but we are given so little information to make sense of them. We don’t know how they were produced, by whom, when, where, or why…

The posters are not presented chronologically or dated, yet we can see dates on some of the actual posters, including lots of posters dated in the 1990s and even 2000s, yet they look almost identical in style to some that appear much older. There are a number of posters signed “H. Chãt” which are dated in the 80s and 90s but are stylistically no different than War-era posters. Was Chãt a poster maker during the War that is now making a living recreating his/her original posters? Are most of the posters in this book created in order to fulfill American and European expectations of the use of propaganda posters in Vietnam long after there native usefulness? Were these posters hung in people’s homes like those in China?

A couple years back a friend brought back posters for me from Vietnam, and they were some of the very same inkjet reproductions reprinted in this book. At the time I assumed these 10″x16″ or so prints were copies of original posters, but now I’m not sure, maybe these are contemporary posters made for the tourist market, and this is their original mode of production? Unfortunately Vietnam Posters does little to clear this up.

In general all the books are nicely produced and well designed, with nice size reproductions of good quality. There are surprising treasures in each. Unfortunately most of the images are poorly labeled and credited across all four books, with little detail about the artists (and no indexes), and in the N. Korea and Vietnam books, no dates of production for any of the posters. Like I said, these are intended as coffee table picture books, not material for researchers or archivists (although unfortunately in the case of Vietnam and N. Korea, there isn’t much else in the way of English-language source material to turn to).