This past week my daughter and I visited fellow Justseeds artist Chip Thomas on the Navajo Reservation. We traveled there for multiple reasons: to spend time with Chip, to see his community, to see the Navajo Nation, to meet others, to see all the Painted Desert Projects in person, and to put up our art under Chips lead and curatorial decisions.

Chip and I have known each other for about five years and I told Chip before traveling that there would be two artists visiting: myself and my nine-year old. There was no way the younger artist could just be an assistant.

We both ran our ideas by Chip months ahead of the visit. I designed three or four options for a project and Chip immediately gravitated towards the Decolonize street sign idea. He then put me in touch with his friends in the community to get more critique and feedback. You can never please all with ones work and never should, but it is all essential as a visitor to a community that you have a host from the community who knows the place well, and knows what type of art will be appropriate or not. That is what makes the Painted Desert Project a community art project: Chip and the majority of artists who visit engage with the local community.

I have always viewed the Painted Desert Project as a bridge between street art and community art. I also wanted to follow the lead of Chip’s past and present work and put up a piece that was positive, respectful, and empowering to Native peoples and history. I wanted the piece to be challenging to all who viewed it, but especially to the non-Native community: something that would make the non-Native tourists who travel across the Navajo Nation to Antelope Canyon, The Navajo National Monument, Monument Valley, and the Grand Canyon think more critically about the landscape and the history.

photo by Chip Thomas

From the start I knew I wanted to do a piece that centered around the word decolonize. The dictionary definition for decolonize is:

verb (used with object), de·col·o·nized, de·col·o·niz·ing.

To release from the status of a colony.

To allow (a colony) to become self-governing or independent.

The focal point on the word decolonize was primarily for non-Native people (including myself) to think more critically about past and present histories of colonization, land use/theft, and systemic racism. With that concept in mind, I designed the signs to look similar to brown roadside signs located across Arizona with the symbol of either a “viewpoint site” or the symbol of a “hiking trail.” I chose the same symbols, font, and colors. The sign with the two hikers suggests that hikers and nature lovers are not left off the hook and that places such as national and state parks are part of the history of colonization and are on stolen lands. I liked the idea that hikers or tourists stopping at a roadside viewpoint would see the signs and would stop and think about what the word decolonize meant to them. They also might think more critically about their own relationship to colonization/decolonization. The fact that the signs looked “official” suggested that confronting colonization was being put forth by the same force that had colonized the land in the first place (the State) which suggests that it was attempting to make amends. Or perhaps, and more realistically, people would see the signs as a culture jam – a critique on the State, systemic racism, and the forces of colonization.

From the start I viewed the project as a collaboration. I designed the image, but Chip would decide upon the locations for the signs. I made seven Decolonize sign, but also one basketball sign with the phrase “Eat, Sleep, Hoop.” I knew the game was very important to Chip’s son who plays college basketball and I wanted to arrive with a gift to the family. This sign celebrates the game and it celebrates basketball courts everywhere, including those on the Navajo Reservation.

During our visit, the process of collaboration unfolded. Chip had thought of sites prior to the visit and I deferred to him on where they should go. At one stage, Chip moved a discarded old couch that had been dumped near a chosen location closer to the sign as to make his own statement: part installation, part staged-photograph.

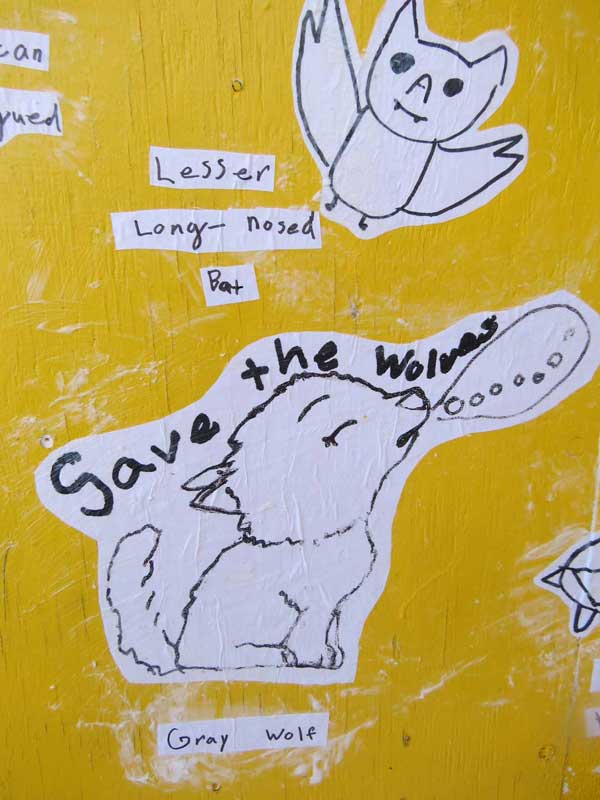

The second artist to put up a piece was my 9-year old daughter. Chip was gracious to include her as an artist in the Painted Desert Project making her the youngest artist to participate in this world-renowned street art/community art project. Her primary interests are animals and art and this was very much expressed in her project.

Prior to the trip she researched endangered animals in Arizona and did drawings that she then photocopied. On the Navajo Reservation, Chip took us to a roadside stand south of Tuba City where Diné women sell jewelry as a possible location for her piece. The roadside stands have featured many previous works by Chip and other invited artists and are such a key part of the community aspect of the Painted Desert Project. Art on the side of the roadside jewelry stands encourages more tourists to stop, pull over, check out the art, and most significantly, conversate with the Native women selling jewelry and to purchase their work. Chip, who has lived on the Navajo Reservation for 30-plus years, has long standing relationship with many of the vendors and he runs by the image ideas by the vendors prior to installing.

During our visit he showed my daughters drawings to Darlene Endischee who immediately requested that the art be put up in her stand. Darlene said she liked her drawings and that they would be good conversation starters for when tourists stopped by her stand. Once permission was received (and after my daughter bought some amazing jewelry from her) she went to work pasting up her art. From the start she wanted to cut out her images and she took joy in collaging them up in an order that appealed to her eye. She also pasted the names of each animal or fish so that viewers would be more informed about the threatened species. When she was done she was proud of her work and I was forever thankful to Chip Thomas and Darlene Endischee for their kindness and support to such a young artist.

This post would not be complete without showing the many other art works from the Painted Desert Project that we passed on our visit. And of course, photos of our amazing host.

art by Alexis Diaz. All other art works by Chip Thomas.