“To Change the World: This traveling exhibit of works by radical artists has a refreshingly old-fashioned air”

by Margaret Regan

Tucson Weekly

03 September 2009

Fabian Garcia Rios was the last known migrant to die in Arizona in the month of July.

The 24-year-old perished in the furnace known as the Tohono O’odham nation on July 31. His cause of death: environmental heat exposure. The young man was one of nine migrants whose bodies were found over six days during the last week of July, and one of 37 who died and were found in Southern Arizona during the whole month.

Fabian is no. 162 on the annual death list compiled by Kat Rodriguez of Tucson’s Coalición de Derechos Humanos. He’s the last one named on her count at the moment, but Kat will soon be adding more. During sweltering August, in the weeks since Fabian suffered in the ghastly heat, 21 more bodies have been found.

The August dead put Kat’s total for fiscal 2009 at 183. With five weeks still to go until the fiscal year ends on Sept. 30, those 183 corpses already equal the number of migrant dead for all of fiscal 2008. And those are only the bodies that have been found.

Young Fabian could easily have served as the model for a poignant work on view in a show of political art at the UA’s Joseph Gross Gallery.

Colored in the sands, blues and greens of the Sonoran Desert, the print by Artemio Rodriguez pictures a desert as flat as the deadly corridor west of the Baboquivari Peak area on the O’odham nation. Gray rocks are scattered over the copper-colored ground. A Gila monster thrusts out its poisonous fangs. A couple of sentinel saguaros rise up under old devil sun, which bears the face of a pointy-bearded Uncle Sam.

One migrant has already collapsed against a rock, while another stumbles along front and center. This one is walking, but he won’t last much longer. He’s already stripped off his shirt in a vain attempt to cool off, and he trudges along bare-chested in blue jeans and sneakers. The toe of one of his shoes has been shorn off by a fierce cactus. His head is bent down—he’s on his way to tumbling over—and beads of sweat jump off his face.

In his mind, he’s in the arms of his beloved. In a thought bubble over his head, colored the black and white of a faded photograph, he and his true love embrace and kiss.

He won’t be seeing her again in this life.

Rodriguez, a member of Justseeds, described in gallery materials as a “radical art cooperative,” has cleverly drawn on traditional Mexican art. His piece wonderfully mimics a traditional woodcut, with rough black cuts and bold outlines throughout. And this being a show called Confronting the Capitalist Crisis, Rodriguez also includes an explanatory text in English and Spanish. Below the title—”Going to Where Globalization Takes Jobs”—he elaborates, “U.S. policy sends hundreds of migrants to their deaths every year as they cross the border.” Pushed from their homes by poverty, they come north to work, to where the jobs are.

This engaging traveling show gathers together 95 graphic prints from the co-op’s artists, who live variously in Brooklyn, Detroit, Pittsburgh and other epicenters of industrial decline. Their work carries on the radical art of the 1930s, when Depression-era artists chronicled the nation’s despair and poverty in vivid woodcuts, linocuts and silkscreens. These contemporary radical artists add offset lithos and stencils to the repertoire of printmaking media, and they use bright colors and bold lines. Even so, their pieces have an old-fashioned air, refreshingly so.

At a time when other contemporary artists are concerned primarily with breaking media boundaries and redefining art, no small thing, the Justseeds folks have an even bigger concern: saving the world. They enlist their art to fight not only against catastrophic U.S. immigration policies, but also against the war in Iraq, environmental destruction, the loss of animal species, the oppression of the Palestinians and the harsh U.S. prison system, among other evils.

“Abolish the Prison Industrial Complex,” cries one work, targeting the for-profit prisons that too often escape legal scrutiny. The words accompany a simple milk carton in white and gray. “Missing,” says the legend over the silhouette of a man’s head, “2.3 million Americans from their family, friends and community.” (The artists who made the 21 pieces in the section on prisons are unidentified.)

“Prisons: Slave Ships on Dry Land,” rages another, pointing up the racial imbalance among the imprisoned in the United States. This artist cleverly imposes architectural drawings of contemporary prison blocks over sketches of the crowded hold of an old slave ship.

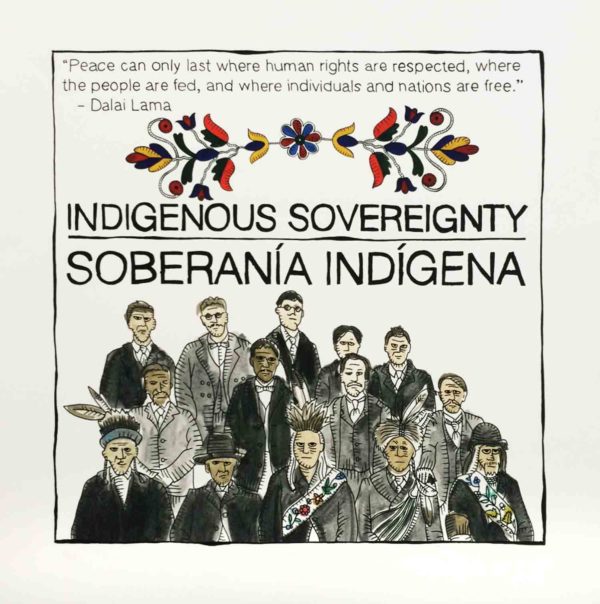

A special section called People’s History has 43 pieces. Heavily weighted with text, these educational works cover everything from “The Battle of Blair Mountain,” a 1921 landmark in the history of mining and labor, to the struggles of the Korean Peasants League, ACT UP Philadelphia and the Mothers of East Los Angeles, who in 1985 successfully fought the construction of a prison in their neighborhood. They make for interesting viewing—the Justseeds artistic standards are high, with varied compositions and creative use of media—and interesting reading. Any one of them could serve as the basis of a dissertation.

In the general section, where the works are signed, an effective anti-war piece uses a screened photo of a city street-corner demonstration. The urban skyscrapers—they could be in lower Manhattan—loom over a solitary woman who’s middle-aged to elderly. She stands alone with her sign, which also serves as the title: “How Many Dead Are Too Many?” Artist Josh MacPhee uses color to emphasize her lonely heroism. She’s been converted into a pink line drawing that makes her stand out sharply against the blue-gray of the photographed streetscape.

Roger Peet laments the possible loss of the endangered hammerhead shark in his vivid “Down the Drain.” Two dense schools of the fish swirl downward into a black hole. The denim-blue fish swim in two spirals of sea-green, separated by a curl of sand-colored yellow.

Occasionally, a work fails in its mission to inform. MacPhee’s “Huelga” (Spanish for strike) has a series of cloudlike circles hovering over what looks like a tipping skyscraper. It’s a startling image, but MacPhee’s meaning is unclear. Could it be an explosion? Capitalism blowing up? In this kind of quick-synopsis art, if you have to ask, the piece doesn’t work.

Quite a few of the prints deal with the unresolved tragedy of illegal immigration. Given current Arizona’s status as the nation’s migrant killing field, they carry special weight here.

Nicolas Lampert recalls past immigration embarrassments in “Welcome Not Welcome.” He’s screened a historic photo of Chinese workers, whose hard labor helped build the West but whose presence was reviled. Melanie Cervantes, in a vivid companion piece to Rodriguez’s picture of the death in the desert, brings up the issue of gay families split apart by archaic immigration laws. She’s made portraits of two loving families with children, one headed by two women, the other by two men. Pictured in bright, flat color, the two groups are separated by a banner trumpeting the slogan “Keep Our Families Together.”

Erik Ruin zeroes in on Arizona’s deadly migrant trail. In an arresting black-and-white woodcut, divided into three verticals that suggest the journey’s length and difficulty, he pictures the relentless surge of the Earth’s dispossessed toward the Promised Land. Mothers, fathers and children walk up and down his panels, down through desert arroyos and up over the border wall.

They’re bowed and strained, laboring to push on, suffering from the exertion. And any one of them could be the next Fabian Garcia Rios