I wrote this piece to accompany the second edition of this print.

If you’re like me, and sorry in advance, you have spent a lot of your life wondering exactly how best to relate to technology; specifically the kinds of technology that are difficult to avoid. You know what I’m talking about; cars, phones, email, etcetera. This means all the tool-forms that we have managed to make almost indispensable to how we navigate the world, and which, since they’re almost entirely built and operated by entities with a profit margin in mind, are aggressively sold to us as such.

It’s only reasonable to expect people who find themselves caught up in periods of whirlwind technological change to find themselves questioning the logic of whatever it is that they’re being asked to use, especially if the tool in question is presented as the only way forward to some better future, or even the only reliable way to maintain oneself and one’s livelihood in an increasingly uncertain present. In general, however, our individual resistances to the adoption of certain novel technological forms are only personally meaningful, as a way of defining ourselves in opposition to a world over which we have little control.

A lot of these ways of manipulating matter and energy are developed and promoted by forces beyond our influence, although not beyond our comprehension. When we notice them approaching, transforming the ways we’ve previously lived or communicated or sustained ourselves, it is usually too late to push back against their momentum. We live today in a world almost completely dominated by technologies that none of us asked for, that few of us have full and effective access to, and which order our lives in ways we hardly understand.

The recent explosion of the phenomenon of the NFT, the Non-Fungible Token, across the metascape of the internet has been almost impossible to ignore. It’s been very like those YouTube channels featuring compilations of Russian dash-cam videos, where you find yourself watching endlessly surprising forms of complex technological disaster, each unfolding one after another before you as you cycle from nervous laughter to real laughter to silent horror and then, in synergy, to nervous, horrified laughter. If you haven’t really been paying attention to this sort of thing, an NFT is basically a digital artifact whose ownership is encoded on the blockchain: a form of digital record-keeping, where each block or record contains information about the one preceding it, forming a kind of interlinked digital receipt that can’t be altered without changing every single entry. Different blockchains are associated with different kinds of cryptocurrency, and their resistance to falsification and alteration is what cryptocurrencies use instead of what ordinary money encodes in the phrase “full faith and credit”: basically a guarantee issued by the government that the money will retain its value. In cryptocurrency the blockchain is the guarantee.

Now that I’ve lost your attention, I’ll keep talking about NFTs.

What people seem to really like about NFTs is that they are new and nifty and associated with the new, nifty qualities of cryptocurrency in general and the endless, heady possibilities of libertarian fiscal flim-flam that the blockchain represents. They are composed, mostly, of digital artworks; meaning any kind of digital image, stored somewhere on a server and visible on some sort of screen. The thing that makes NFTs exciting, and which makes each one ostensibly unique, is that the token in question isn’t actually the artwork- it’s a sort of receipt, located on the blockchain, that points to the artwork. The fact that the location of the token on the blockchain can be legally owned by an individual means that the digital image itself has suddenly been transformed from an object infinitely reproducible and copyable into something that can be identified solely by this one location on this one big receipt. So instead of being something you can just screenshot or right-click and save to your desktop, the digital image becomes unique. And most importantly- it can be sold.

Of course, this is total horseshit; you can still just screenshot the image. But, the enthusiasts say, the only way to prove that it’s the real image is to see if it’s the one that the blockchain receipt points to.

Who cares, I hear you cry.

Well, people are making a lot of money out of this crap.

It’s been a little disheartening to watch people whose art I respect get involved in the hubbub surrounding NFTs. I’ve had to unfollow a few people. But hey, artists need to make a living and if this is a way to grow an audience, who am I to complain? Go right ahead, I say, just don’t make me look at it.

What the whole thing has revealed is something that wasn’t exactly hidden in the first place: that the function of the art market is to produce objects of value; and that those objects are really only useful if their value can be said to appreciate.

This is why art is such a popular way to launder money- huge sums of cash can be used to purchase small physical objects in which that money suddenly becomes stored, and can presumably be released again at a later date if it should prove necessary. The fact that rare artworks appreciate in value according to certain arcane factors related to history, politics and taste, means that you might even get more money out of the deal further down the road whenever you sell it. This is easier to deal with than real estate, another historically reliable method of laundering money: Art you can just pick up and move around. This is what is now happening with NFTs.

The real power and benefit of the NFT becomes immediately visible: even art objects have to be stored somewhere, they have to be kept clean, they have to be maintained in climate controlled environments, that sort of thing. They have to be carefully packed for shipping. A digital artwork is simply a precisely coded series of numbers: it can’t get rained on, and it can be transferred instantly to anywhere in the world at zero cost.

One other awkward thing about artworks is that they have to be kept safe. The black market for stolen artworks is around eight billion dollars per year, and you might expect that since NFTs are essentially just little pieces of cryptography stored on computers, they would be difficult to steal as well. Of course this is not the case. This is where it starts to get funny, if you were wondering.

Just as NFT popularity has exploded, so has their theft. Perhaps the most amusing instance is the case of the New York art dealer Todd Kramer, who posted on Twitter on December 30th 2021 the immortal phrase “I been hacked. All my apes gone. This just sold please help me.” Kramer was referring to the numerous NFTs that he owned from the “Bored Ape Yacht Club” NFT series, a collection of shitty cartoon drawings of simians that follow a theme that many NFT-farmers (ranchers?) have used as the craze has taken off: use an algorithm to generate a digital composite image based on a cartoon template and adjust randomly certain factors like hair color, sunglasses, and teeth. Then sell it.

Thieves accessed Kramer’s digital “wallet” where the tokens or receipts that point to his purchases reside, and absconded with the entire suite of various numbers that refer to other numbers encoding a variety of crap doodles of cartoon apes. He tweeted later that he had found a few of them on the OpenSea NFT market, an online service where NFTs are bought and sold, and that several of them had already been sold before he convinced the operators to freeze the sale of the rest of them.

The thing about selling NFTs though is this: once a transaction has occurred in the blockchain, it can’t be reversed. You can’t cut that transaction out of the endless chain of receipts and reverse it without destroying the entire system. So selling stolen NFTs might just be the perfect crime.

This is true of all cryptocurrency, and perhaps best illustrated by what happened when thieves stole $60 million worth of the Ethereum cryptocurrency in 2016: to get the money back, operators had to split the blockchain into two segments and destroy the one where the theft had occurred. Since this required destroying every transaction that happened after the theft, it made a lot of people angry and showed just how difficult it is to deal with theft in these ridiculous contexts.

So why do people like these things? What’s the point, outside of being able to hide massive amounts of money that you made from your sales of drugs or guns or whatever to assorted national governments or the people who are trying to depose them? Most people aren’t sitting on huge piles of cash that they made from selling fentanyl, so what is it that they are getting out of all of this?

Apart from the cool factor, which is of course a major motivator, the thing that a lot of people like about NFTs and about cryptocurrency in general is its independence from centralized authorities; things like central banks and national police forces. The activities that take place on the blockchain are administered outside of the normative systems of monetary control that most societies use to buy and sell; and they are also not really subject to the authority of established forces of order. So they have an appeal to people who distrust such entities; people interested in avoiding taxes and other libertarian bugbears. The blockchain is a manifestation of the trust that people need to have in a currency in order for it to retain its value. Instead of that value being backed, as in the time before NIxon, by big piles of gold bars in Fort Knox, or in the post-Nixon era by simply the obvious imperial power and global domination of the United States Empire and its more than 800 international military bases, it is now backed by the uncrackable certainty of this kind of ironclad ledger, recording all transactions in the most unbreakable code imaginable.

Except, as previously observed, for when it isn’t. So if it’s so easy to steal this shit and the guarantee of authenticity is only a guarantee for the wealthiest participants, what makes it worth the pixels it’s typed on? You may well ask. The answer might lie in the scam itself- Cryptocurrency and NFTs are designed with crime in mind: the crime, in this circumstance, is the point. You might say that the essence of capitalism is crime, and I wouldn’t argue with you. It’s always been that way. The process of forcing people to pay you for things that they either need desperately to live or alternately don’t need at all, things that keep them barely alive or actually kill them, is the basic and most fundamental definition of an anti-social activity.

The key to any currency is how it maintains its value, and how effectively the value is stored inside it. How does it get in there? How do you calculate it? A currency is a symbol that people use to determine the equivalency of the value of disparate goods or services, with each good or service being rated according to the number of units of the currency that it is equivalent to. The currency can then be used to acquire other goods and services that are rated at the same number of units. Equally importantly, the currency can be used to exchange for other currencies that can be used in different locations around the world; for the purposes of paying for the goods and services that are available in those locations.

The rise of global capitalism was in large part a struggle to create systems wherein those understandings of value could be standardized, and the value understood to be encoded in one currency could be transferred effectively and with minimal trickery and loss to other currencies. This was very important in the context of expanding networks of global trade, where the value of objects and the labor required to produce them might pass into and out of four or five or ten different currency systems before it made its way from, for example, the Spice Islands of the Moluccas to the trading desk of an import company in Amsterdam.

The dominance of these mechanisms of exchange was taken up, over the course of the history of capitalism, by four successive imperiums: the Genoese, the Dutch, the British, and the Americans. Giovanni Arrighi’s amazing book The Long Twentieth Century describes in great detail how these successive mercantile empires rose, dominated, and then fell- each first by taking firm control over massive sections of the world’s markets, the sites of exchange of goods, services and – crucially – currency. As the successive empires of mercantile capitalism extended themselves across the world in spasms of spectacular savagery and rapaciousness, they strove at all times to make the process smoother and more quantifiable.

Each system followed a similar circular path to the others as they succeeded each other, cycling through history from the 13th century to the present day and each overlapping with the next as they passed through a set of surprisingly consistent and perhaps at this point predictable stages: advancing their own mechanisms of market capture and control, dominating both the world’s demand and supply for an overwhelming variety of goods and services, and then passing beyond the everyday brutality of their manipulation of real-world objects and the people that manipulate them into a realm of pure financialization, where each empire lost itself in turn in the manipulations of raw numbers and the value caught up within them. As each of these empires passed further into the realms of total financialization, their stars began to fade from the firmament and they withdrew, slowly, into a deepening shadow, as the upstart empires which had been waiting in that shadow burst suddenly into the light.

It happened like clockwork: the Genoese city states establishing the first cycle only to be supplanted by the Dutch as they moved to convert the riches they’d made from the earliest colonial adventures into speculative investments. The Dutch in turn dominated the world through the East India Company only to withdraw later into abstract financializations of the money it had brought them. The British rose next, and built the widest ranging empire yet, enfolding properties on every continent into their market dominance until, after the second World War, the Americans finally strode forth to create the broadest empire that the world had ever seen, even if it was hardly as visible as the others; even all those military bases remain still more or less imperially deniable. But during the 1970’s the American empire began to dematerialize; beginning in New York, the forces of American finance began to consume themselves, vaporizing into realms of purely digital money whose totality became evident during the stock market crash of 2008- where suddenly it was revealed that all there was out there was money, and there was no reason to believe that any of it was real.

The world of American finance clawed its way back from that brink within massive investments of actual liquid capital, but the process of financialization continued, with the arrival on the scene of cryptocurrency perhaps the strangest denouement of the old story imaginable. As the new forms of blockchain-based currencies proliferate through the internet, each coin with a stupider name and more bogus fiscal premise than the last, the end-empire game of financial disincorporation has finally reached the stage of farce.

The irony of the history of capitalism as seen through this lens is that even though it started out as a way to make currencies legible to each other, and thus create larger, more powerful currencies that could dominate the weaker ones, we now see a strange inversion of the process taking shape: the new currencies are isolates, each written on their own forks of the larger blockchain, branching out like a tree into their own weird, darkend silos, unexchangeable, unalterable, and locked into an unstoppable forward motion, which from one direction might look like progress but with the head turned in another direction looks like a headlong plunge into nothingness.

We live in the ashes of this fire, surrounded by the swirl of monetary particles tearing themselves to pieces and vanishing down the drain. As this current cycle ends, we can see the American empire struggling to not go quietly into the same transporter-beam that dematerialized its predecessors. Maybe cryptocurrency is the last gasp of that system, the antagonist atomizing themselves just like at the end of so many movies, a swirl of motes caught up in whatever passes for wind these days, scattering across the landscape like so much dust. It is clear which empire is rising to replace the one we currently inhabit- what isn’t certain is if this transition will involve, as each of the preceding ones has, an increasingly global and devastating war.

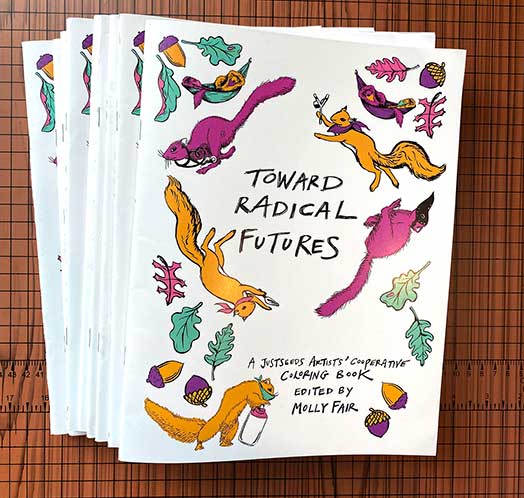

None of this has to be this way, however, although our means of escaping it are increasingly uncertain. If the profuse and glorious diversity of human culture is any example, then we can surely make whatever world we want to live in- the problem is that we are always trying to make it within the world that is already here. Simply creating a little snow-globe version of the world that we imagine we want and pretending that it can prefigure a larger version of itself is just fantasy, and each of those little worlds will always seem to be getting further and further away from us, and getting smaller as they go. A larger vision of a world entire that serves all its people, and all its non-people too, is something that will only emerge from the struggles we wage against the world as it is.