Here is an essay by Jesse about the piece and Clare’s lament about the destruction of the commons.:

Ah cruel foes with plenty blest

So ankering after more

To lay the greens and pastures waste

Which profited before

(John Clare, The Lamentations of Round Oak Waters)

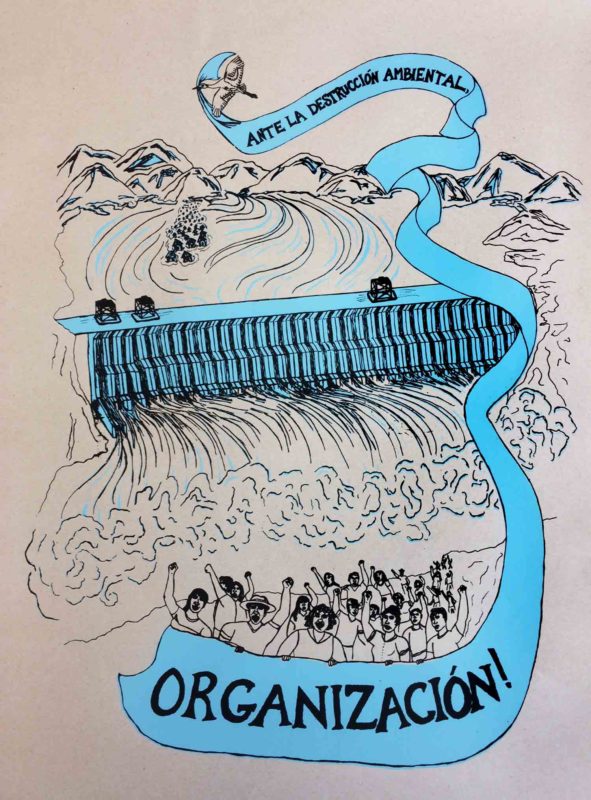

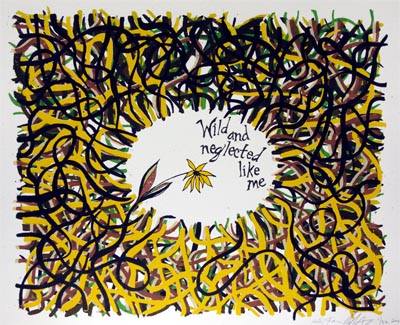

Recently, Molly and I made a print based on a line from John Clare’s poetry: a love poem written to a weed. The poem offers some interesting insights into commoning as a way of life, and in particular how unused, unnoticed, and untamed natures – which capitalists saw as wasted resources, were a source of value to the commoners that lived on them. Commoning was an entirely different way of relating to the world, than what comes to be naturalized through our capital-infused culture. There’s so much interest in the idea of commons today – whether digital commons, cultural commons, political commons – but less attention is spent on understanding commoning and private property as qualitatively different relationships to the world.

So, I thought it could be a good idea to use Clare’s poem as an entry point, to go back to the history of English commons and reflect on this way of life, especially some of the different sorts of ‘values’ and ‘wastes’ that it entailed. These are values and wastes that are still with us today, and appreciating them in a new light might help us find some of the radical possibilities that lurk in the most mundane and overlooked corners of our social lives and landscapes.

Clare was a peasant who lived in Northamptonshire during the first half of the 19th century. His poetry bares witness to the destruction of the vibrant common field communities that had defined the English countryside for centuries. Enclosure was a central part of this transformation. It was a legal process that changed the property status of common lands, making them available to be partitioned into individual plots of land that could be used in profit maximizing ways.

In the common field community, there was no conception of natural resources like the concept that prevails today. Instead, there was an understanding that nature, and the people using nature, were resourceful. No one individual ever had complete control over a discrete part of common lands; all uses of the land were mediated by customary and common right relationships that determined who could use what parts of the common lands, when they could use them, how they could use them, and who they could use them for. So for instance, one customary restriction on the gathering of dead branches from the waste lands would be to only allow branches to be collected “by hook or by crook.” This meant that one must use either a weed hook or a sheep crook to pull off branches, therefore disallowing any more efficient alternatives, as well as preventing anyone whose primary work did not necessitate one of these two implements from collecting wood.

Here I just introduced a new concept: waste lands. The wastes were an essential portion of the common lands. Fens, furze, heath, woodlands, etc., each waste provided important resources to local inhabitants, depending on the specificities of local ecology. The waste might serve as a quarry for stone or minerals or a storehouse for charcoal. It might provide peasants with bark for tanning, bees to collect honey and wax, grasses to cut as hay, and even small game. When wooded, waste land provided both a source of timber and kindling as well allowed for pannage, which was the practice of allowing the village swine to forage on acorns and other nuts that fell from the trees. But the waste lands were much more than a source of necessary provisions, they were also a lived space, a terrain of everyday life.

The waste lands were both a space for shared activities (including dissent) and a place for solitude. Most work on the waste was done by women and children. Children grew up not only working and foraging, but as well playing in the waste. These activities were often inseperable; what the geographer Cindi Katz has called the ‘workful play and playful work’ of child labor in a self-provisioning economy.

Dennis Potter recounts his childhood in the Forest of Dean, “This is the children’s Forest too. A place to collect birds’ eggs and build secret cabins in the thickest parts of the Wood, to climb trees and search out and occupy abandoned quarries or old, disused pits, smelling with stale, silvery mud caked over rested rails. Adults, too, have always had this background… surprise still revolves through the year – the myriad greens, the walks down an old stony road to the rapids, the bracken turning and crumbling into a dusty and universal golden brown, and, even in winter, the stark black trunks and icy stubble has its own bitter loveliness.” (quoted in Janet Neeson, Commoners)

In his reflections on village life, Michael Bourne romanticizes the common right community of his past, and explains how it had an almost ritualized existence, where value emerged through the customs of everyday life. He writes, “in this parish, when, on an auspiscious evening of spring, a man and wife went out far across the common to get rushes for the wife’s hop-tying, of course it was a consideration of thrift that sent them off; but an idea of doing the right piece of country routine at the right time gave value to the little expedition.” (Bourne, 122) There was value to common right that could not be reduced to any calculation of its ‘economic’ or ‘market’ worth. Janet Neeson, in her book on Commoners, writes, “Evidently critics did not know that a waste might provide much more than fuel. Sauntering after a grazing cow, snaring rabbits and birds, fishing, looking for wood, watercress, nuts or spring flowers, gathering teazles, rushes, mushrooms or berries, and cutting peat and turves were all part of a commoning economy and a commoning way of life invisible to outsiders.” (40) This invisible life of the waste lands, teaming with values that are qualitatively different than the values associated with profit, are where Clare’s love poem enters into the picture:

TO AN INSIGNIFICANT FLOWER,

OBSCURELY BLOOMING IN A LONELY WILD.

-John Clare

And though thou seem’st a weedling wild,

Wild and neglected like me,

Thou still art dear to Nature’s child,

And I will stop to notice thee.

For oft, like thee, in wild retreat,

Array’d in humble garb like thee,

There’s many a seeming weed proves sweet,

As sweet as garden-flowers can be.

And, like to thee, each seeming weed

Flowers unregarded; like to thee,

Without improvement, runs to seed,

Wild and neglected like me.

And like to thee, when Beauty’s cloth’d

In lowly raiment like to thee,

Disdainful Pride, by Beauty loath’d,

No beauties there can ever see.

For, like to thee, my Emma blows,

A flower like thee I dearly prize;

And, like to thee, her humble clothes

Hide every charm from prouder eyes.

But though, like thee, a lowly flower,

If fancied by a polish’d eye,

She soon would bloom beyond my power,

The finest flower beneath the sky.

And, like to thee, lives many a swain

With genious blest; but, like to thee,

So humble, lowly, mean, and plain,

No one will notice them, – or me.

So, like to thee, they live unknown,

Wild weeds obscure; and, like to thee,

Their sweets are sweet to them alone:

The only pleasure known to me.

Yet when I’m dead, let’s hope I have

Some friends in store, as I’m to thee,

That will find out my lowly grave,

And heave a sigh to notice me.

In many ways the poem speaks for itself, but I will point out a few things:

1. During the struggles against enclosure, the “weed” was a forceful metaphor for both common land and commoners. For those advocating improvement and enclosure, the weed was a persistent nuisance that needed to be weeded out of the landscape. For those resisting enclosure, the weed symbolized endurance, strength, and the ability to persevere in harsh conditions. The weed was the sturdy commoner, who once noticed, would “bloom beyond my power.”

2. The strength of the weed was in its untamed state: “Without improvement, runs to seed, Wild and neglected like me.” As you may have already gathered, “improvement” was the term used for profit maximizing agriculture. An improved farm was one that no longer operated according to customary values, but instead according to the dictates of the market. Hence, the justification for enclosure was inseperable from the faith in improvement. Clare’s weed refers to the power of the unimproved common lands, and the commoners who remained “wild and neglected” through their resistance to enclosure.

At initial glance, the ending to the poem seems rather somber, with a sigh heaved in remembrance of a deceased commoner. But I think there is a more inspiring way to interpret this ending – one that implicates all of us who choose to befriend the lost commons, to find their lowly grave, and in training upon them with our “polish’d eye,” help them to bloom again. So what does it mean to train our eyes upon these lowly wastes? I think this is an important question to ask – and I think it has everything to do with how we value the world around us – both human and non human alike – and whether, when we see “wastes” whether wasted time or wasted places or wasted things, we are able to find and respect the values that they provide… without first translating them into money or its equivalence.