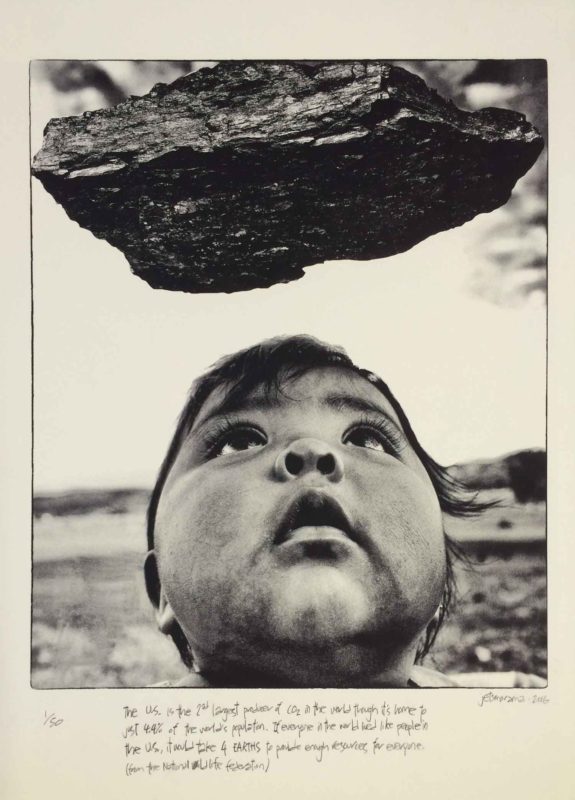

Humanist and documentary photographer Dan Budnik is best known for his black and white photography from the civil rights era. It was Dan’s photo of Dr. King that appeared on the cover of Time magazine when Dr. King was assassinated. After covering the civil rights movement from 1964 – 66 Dan gradually made his way to northern Arizona where he’d heard of a longstanding land dispute between Navajo + Hopi tribes. In 1984 the dispute resulted in approximately 9000 of 180,000 Navajo tribal members being forcibly relocated from ancestral land where they were primarily sheep and cattle herders in exchange for life in prefabricated homes. Sadly, many of the people relocated didn’t have the income to cover utilities as they’d formerly made their livelihood from their animals. Many found themselves homeless. However, a group of elders refused to leave their ancestral homeland and to this day continue to protest forced relocation.

Dan’s images of the land dispute generated interest in a documentary film on the subject titled “Broken Rainbow” which won an Academy Award in 1985 for best documentary. As noted on the promo poster for the film “There is no word for relocation in the Navajo language; to relocate is to disappear and never been seen again.”

I was asked recently by curator Erin Elder to consider submitting work for a pop up show critically evaluating land use in a capitalist economy (for the Museum of Capitalism in Oakland). She says of her portion of the show titled American Domain “…Under capitalism, land is measured, marked, bounded, guarded, and owned; it is a commodity, a site of production, and oftentimes, capitalism’s dumping ground. Though land ownership is not an inherently American phenomenon, the United States was founded on a land grab and its identity has been consistently wrapped up with the economics of territory. Through artists’ work about fences and walls, boundaries and their trespass, American Domain examines notions of property and ownership.”

Dan’s images from his time at Big Mountain immediately came to mind. I approached him about using one of his images for an installation and found him to be excited by the idea. Next I sought out a part time resident of Big Mountain whose mother was active in the relocation resistance. We agreed that in light of the ongoing struggles of First Nations people to maintain sovereignty over their land this image is as timely now as it was when it was taken circa 1984 and he consented to its use.

The United States Flag Code

Title 4, Chapter 1

The flag should never be displayed with the union down, except as a signal of dire distress in instances of extreme danger to life or property.

Installing the image over a week in Oakland led to several insightful moments such as the police officer who pointed out the flag was upside down as he passed in his cruiser or the fireman who stopped his firetruck, got out and engaged me in conversation about the photo. The most compelling interaction was with a vet who vehemently proclaimed one evening while I was on the lift that he fought for that flag and didn’t appreciate seeing it upside down. He concluded by saying “Trump 2017!” Two days later he returned and shared that after 8 years of combat in Afghanistan seeing things no one should ever see he now suffers from PTSD, sleeps poorly and can’t hold a job. Things set him off easily and he has trouble controlling his emotions. He said he’d gone into service believing in this country and it’s promise of democracy both here and abroad only to realize he’d wasted 8 years of his life and is a changed man. He apologized for his aggressive tone 2 days earlier and cried as he recounted some of his life experiences. I thanked him for returning and providing an opportunity for discussion. We shook hands and embraced before he headed on his way.

man carrying items to recycling center at dawn

photo by claudia escobar

Brooklyn Street Art article is here.

For more information on this ongoing struggle, check www.supportblackmesa.org.