The sixth installment of Dispatches, an ongoing short interview series with political artists working around the world. This time we feature Junk Comix aka Edmund Trueman, an itinerant artist who produces political comics about squatting, migration, imperialism, and anti-colonialism.

Will you tell us a little about yourself? Who are you? Where do you live?

My name is Edmund Trueman and I often publish my work under the alias of Junk Comix. I live in a small truck which is almost always parked in or around some squatted building or terrain in Western Europe. I’ve been involved in the squatting movement for the last 8 years or so, and I’ve been drawing, making comics, and generally telling stories with images for as long as I can remember.

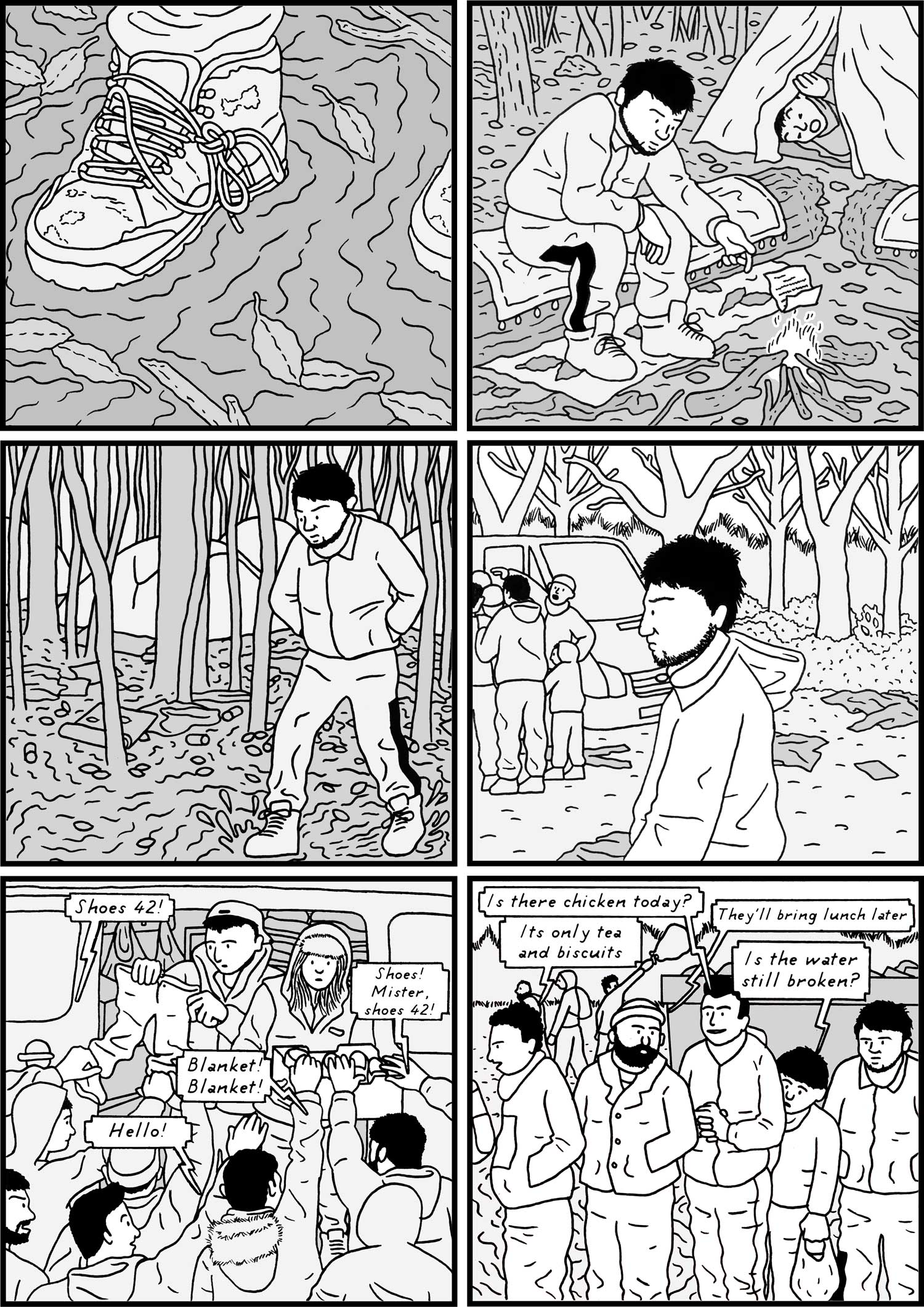

Can you talk to us about your project Postcards from Congo? I’ve seen images covering many different timeframes and multiple historical and cultural reference points. What is the scope of the project and how did it come to be?

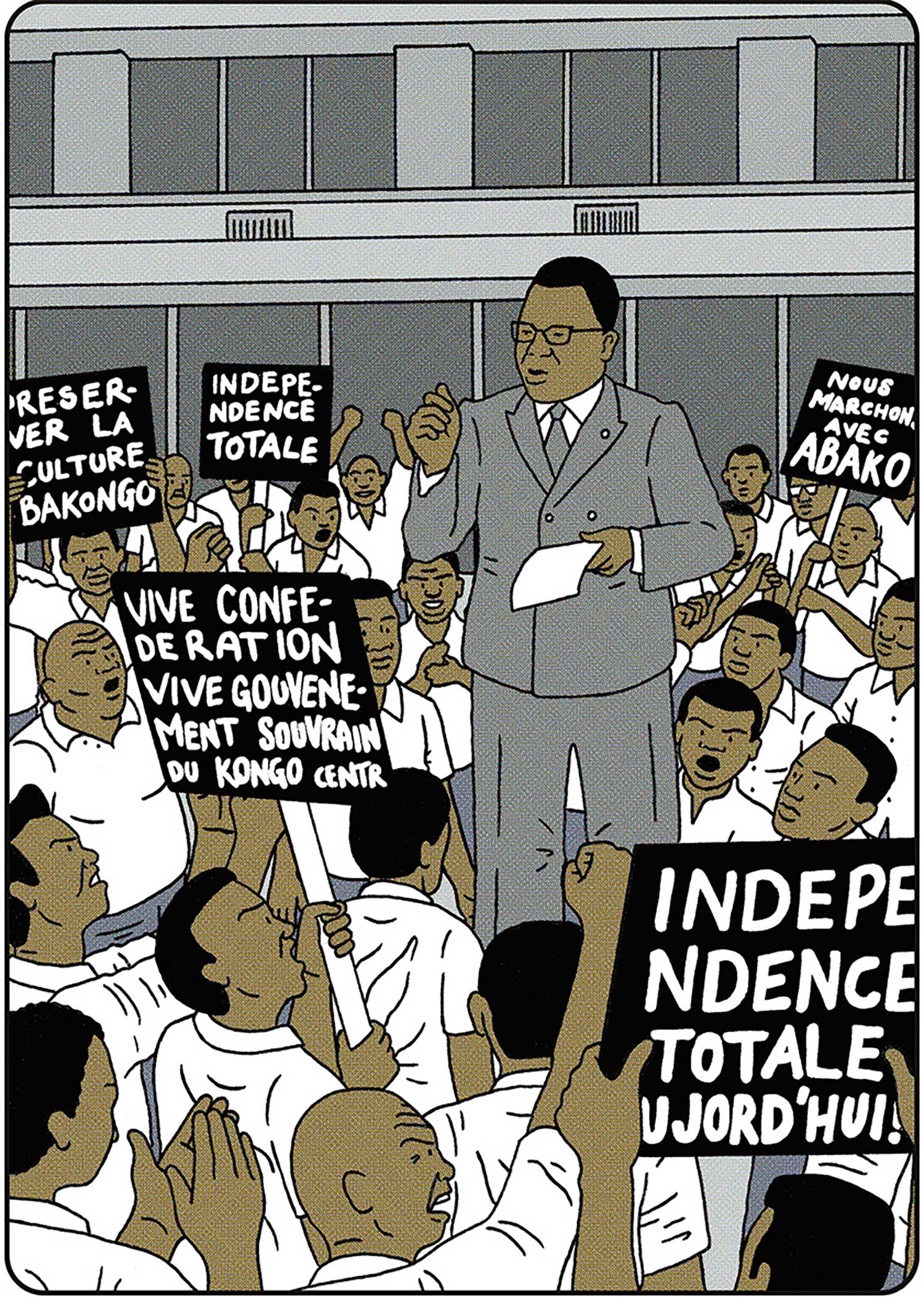

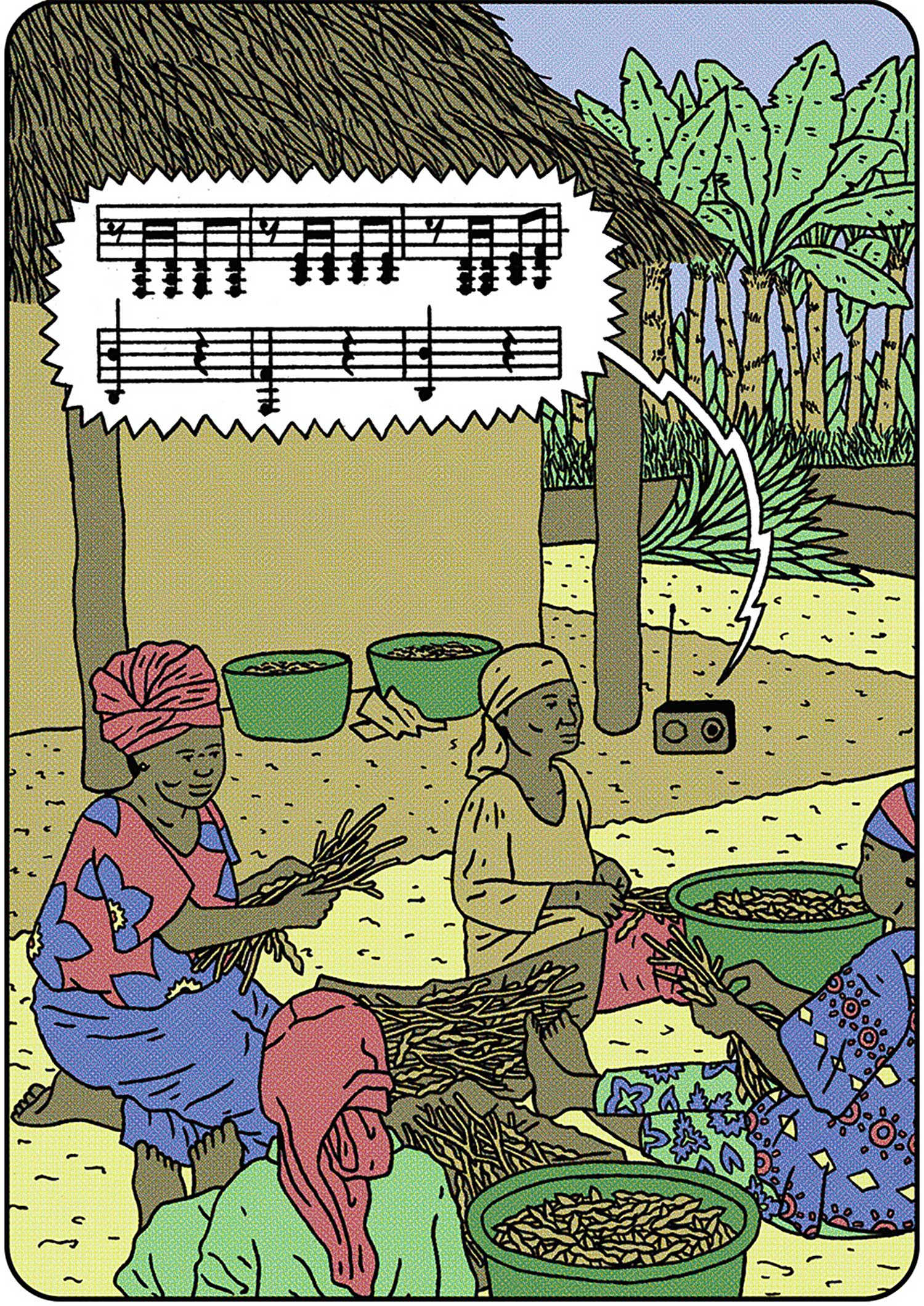

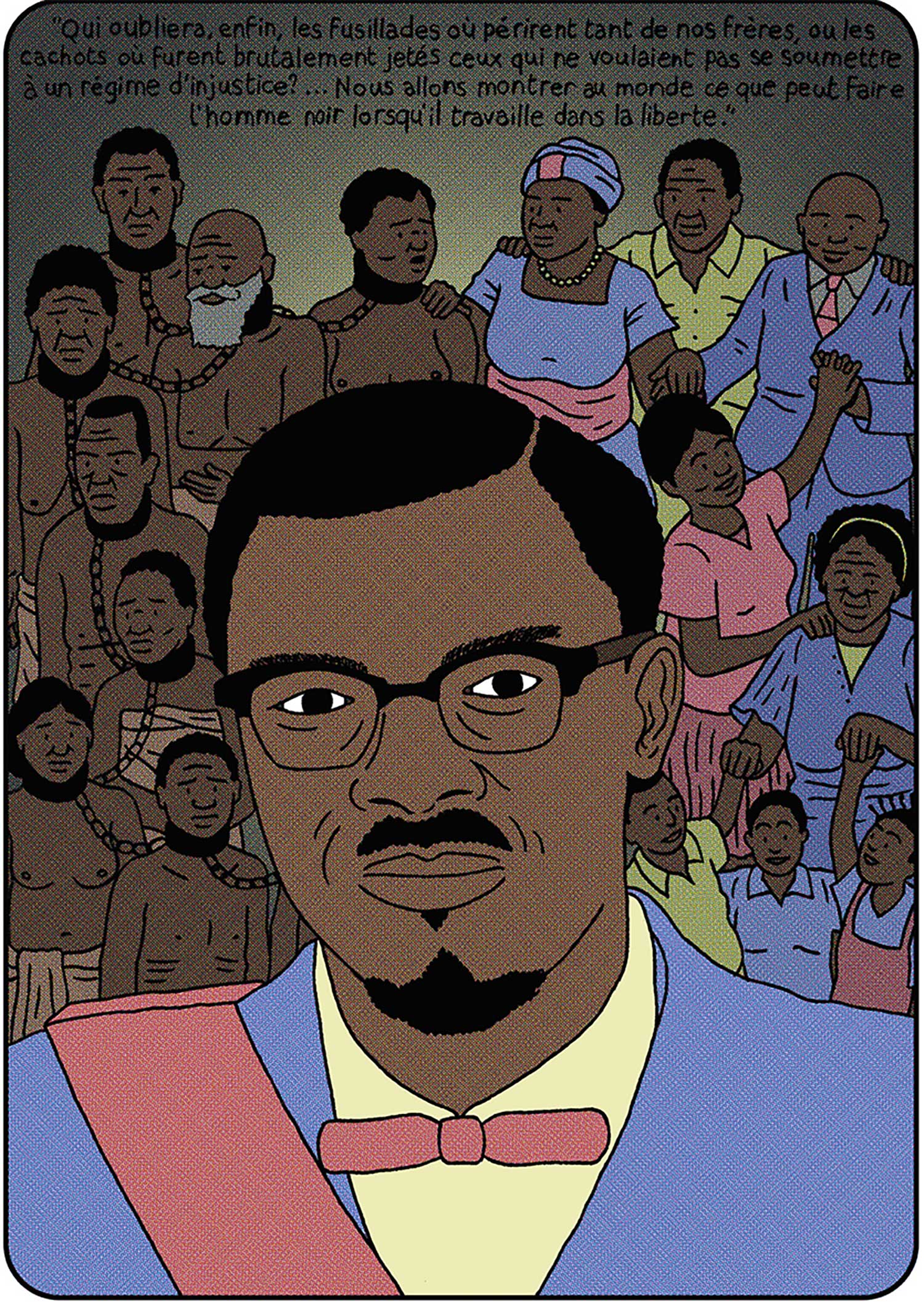

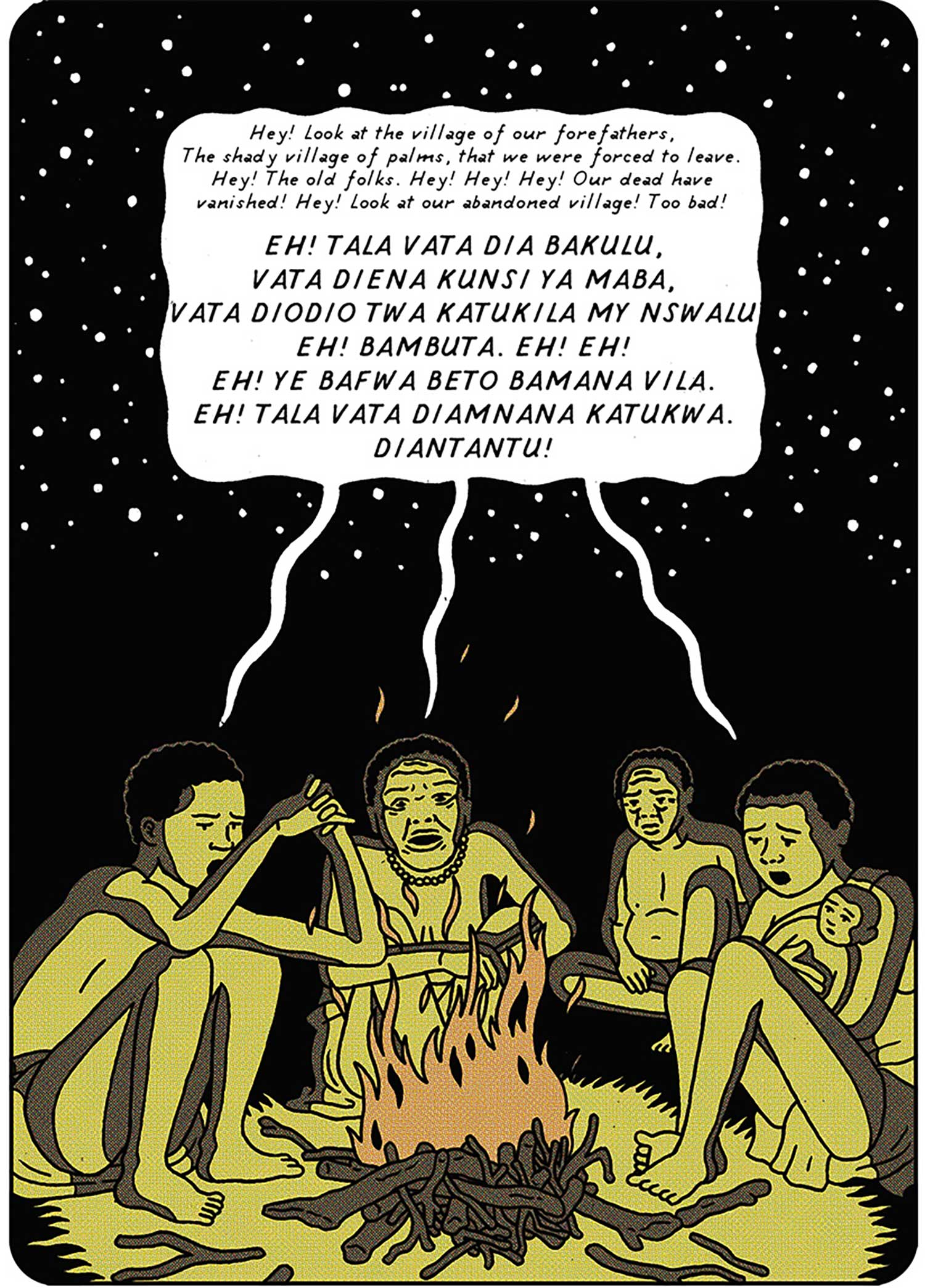

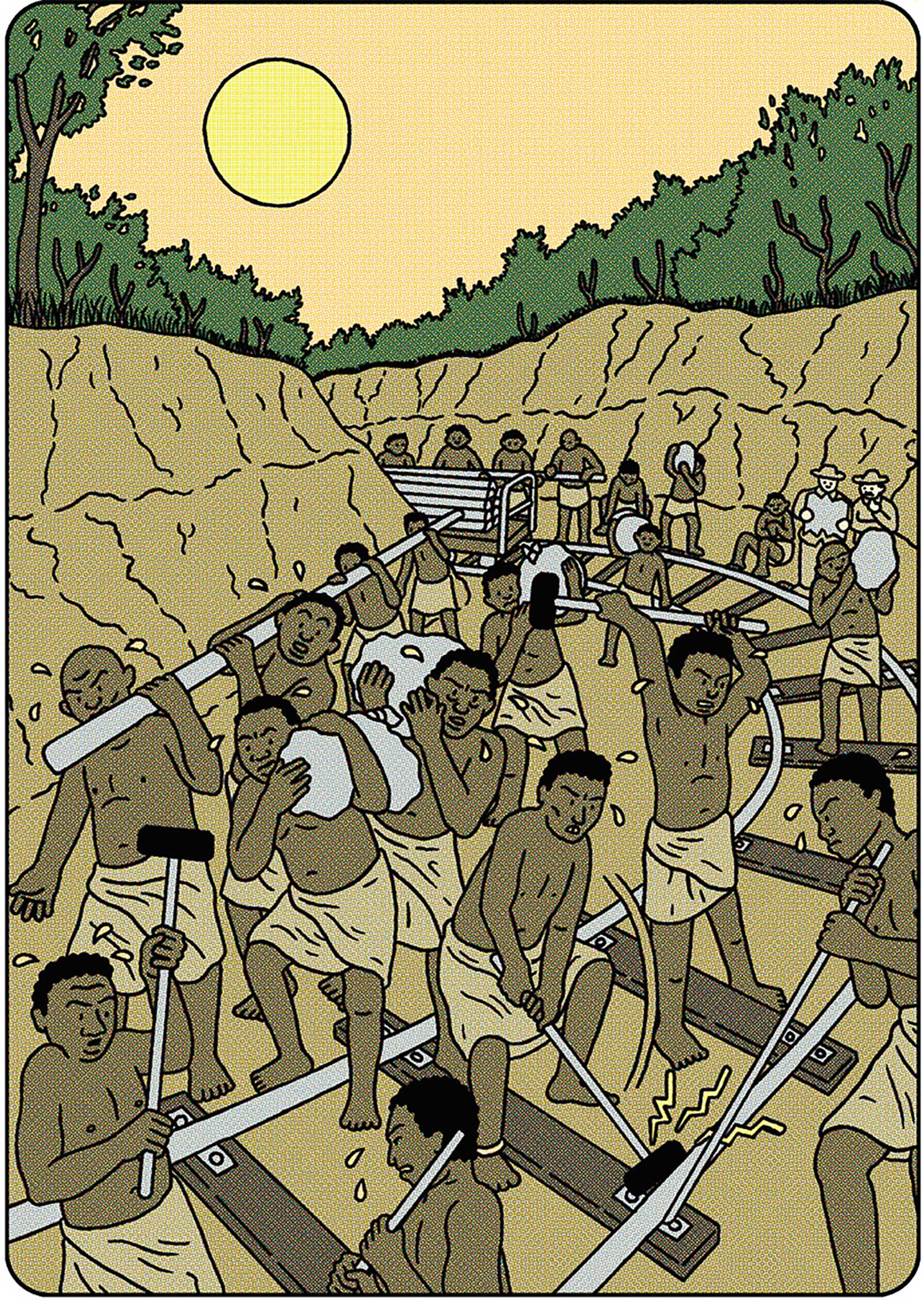

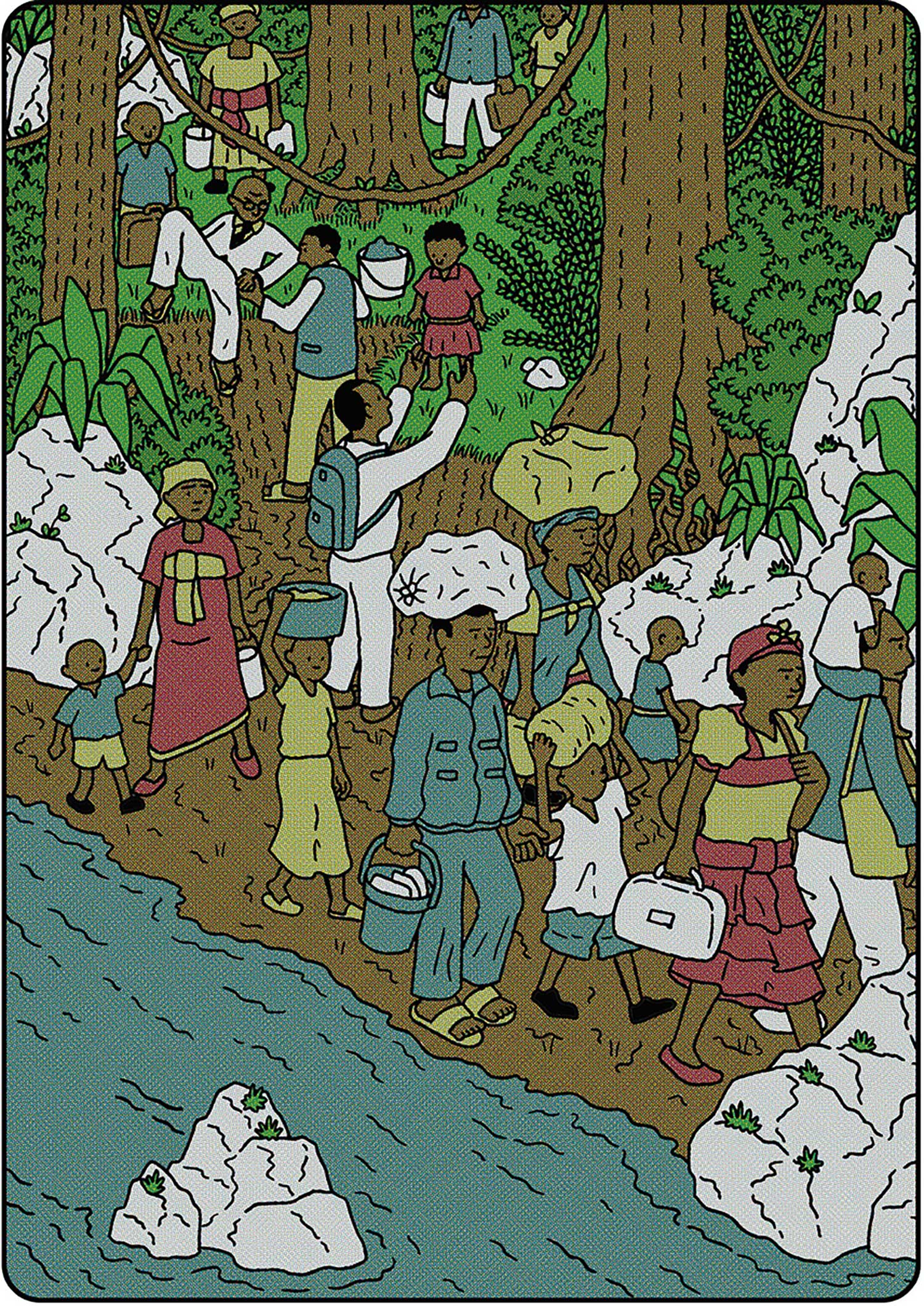

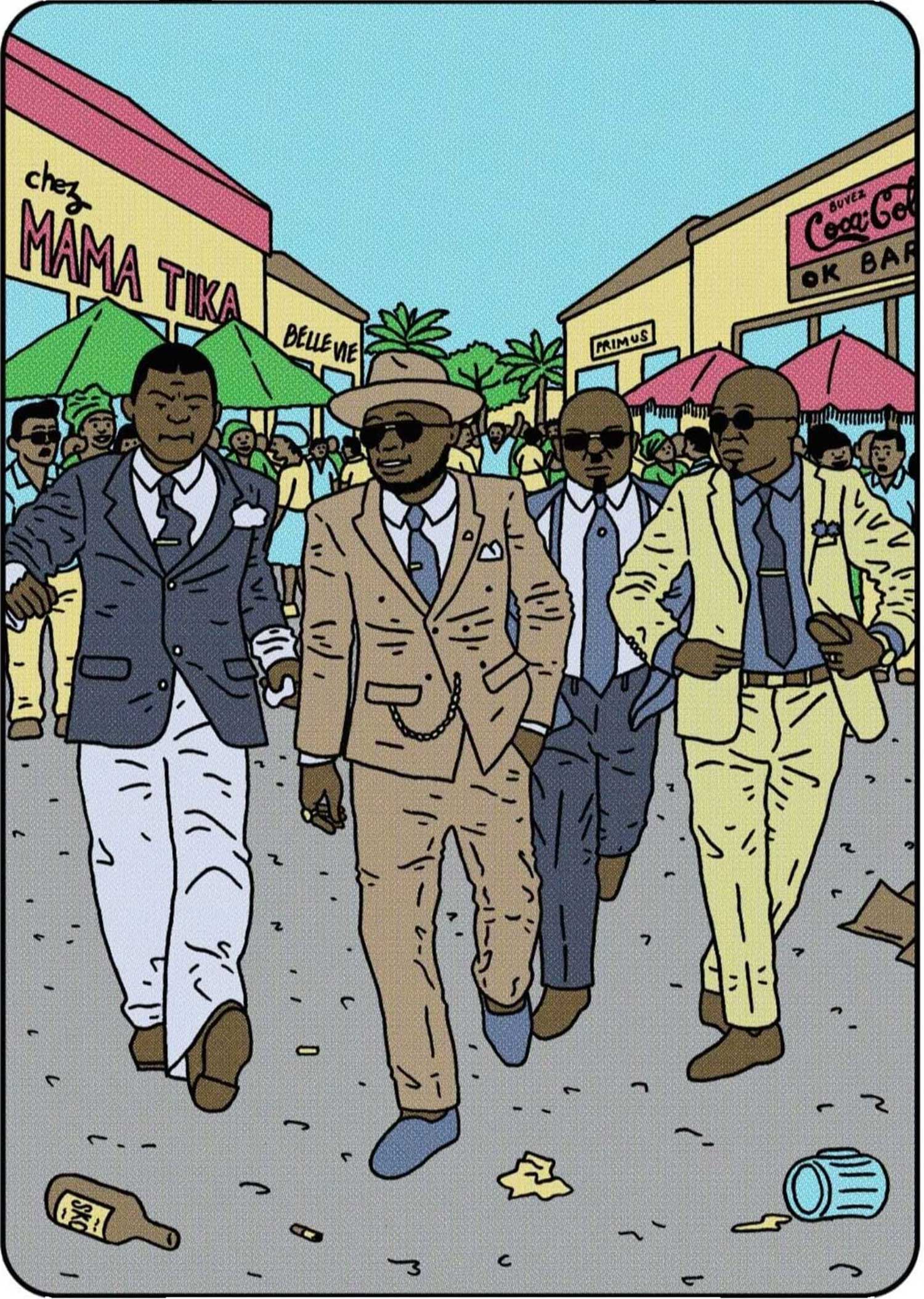

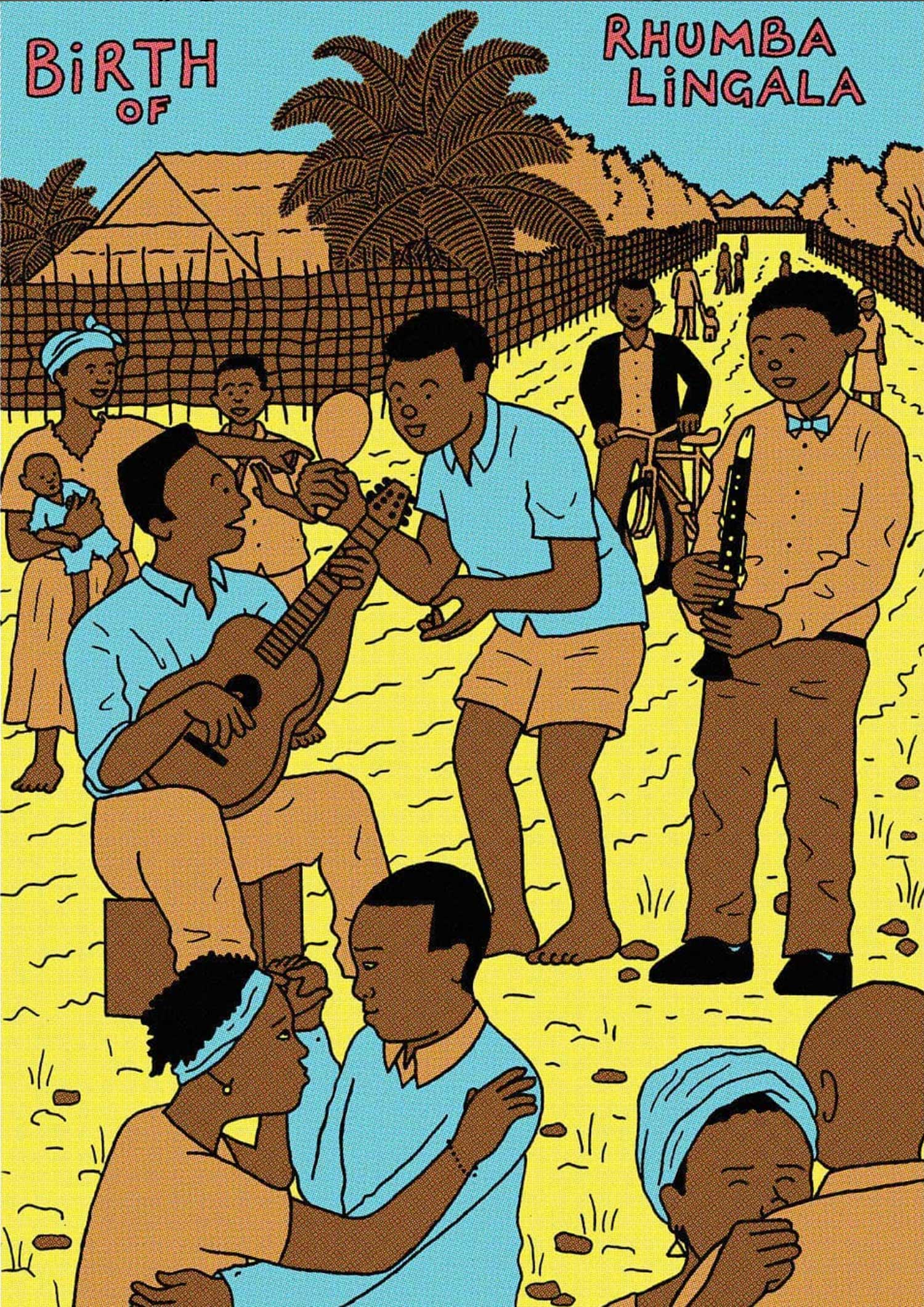

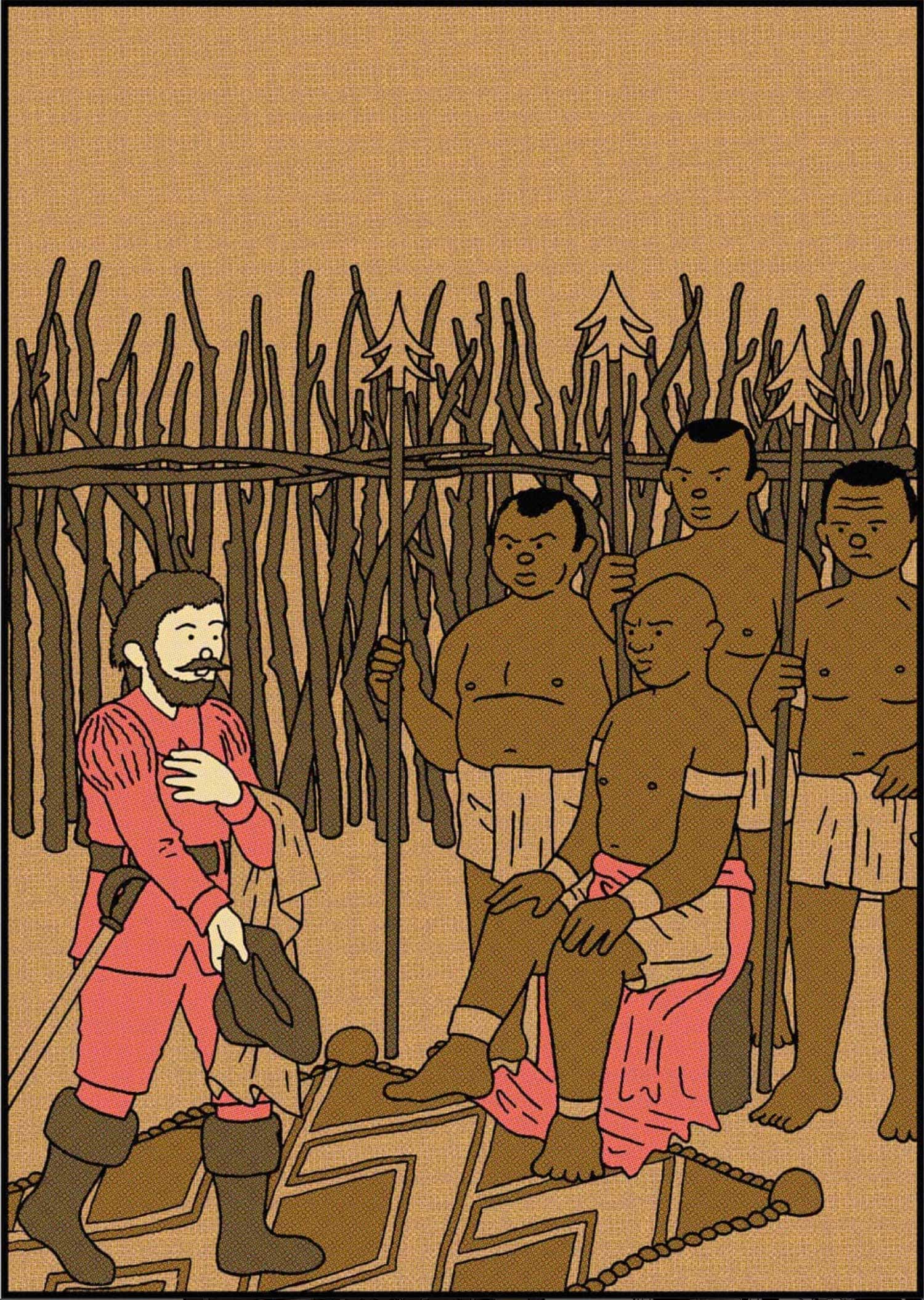

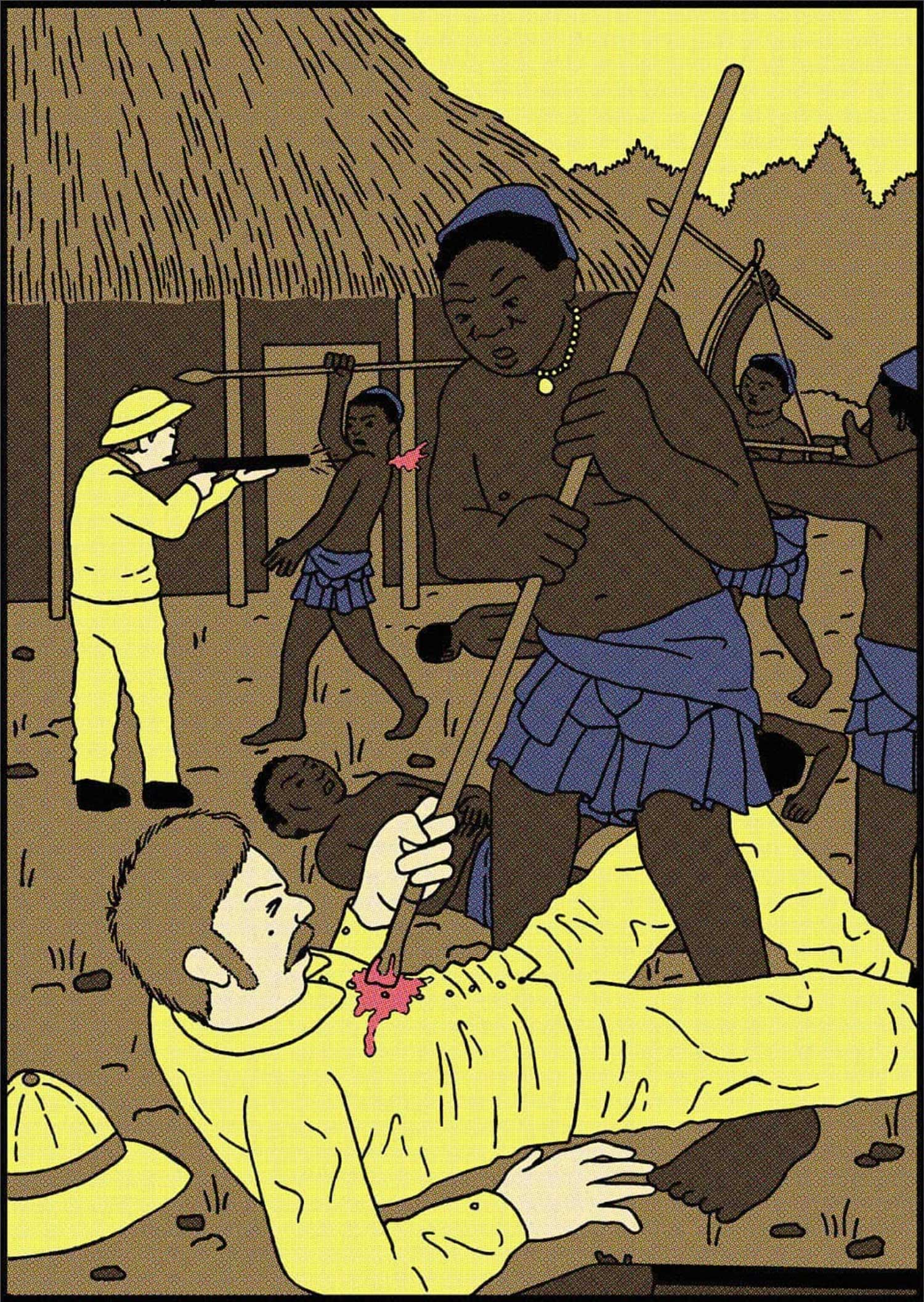

Postcards from Congo is an introduction to the history of Congo, told through a series of colorful, illustrated snapshots (or, postcards) – individual events or moments in time.

The idea is to present the story in an appealing and accessible way, which can introduce the story to new audiences but also adds a new level to those who are already familiar. I think works like this are especially important to reach out to young people, as well as those who are just less likely to pick up large bodies of text. The book doesn’t only focus on the history of political development, but also on social movements, cultural development and the lived daily experience of regular folks. I hope there’s some things in there that will be new even to people who are already familiar with this history.

How did this book come about? Here in Europe there’s generally a pretty dim awareness of what is going on at the moment in Africa. A few years ago I started trying to combat my own part in this ignorance by educating myself a little about the modern history there. I don’t claim to be any kind of expert, but somehow I got really stuck on the story of Congo. Its a very gripping story, a story with a lot of hope and determination in the face of adversity, but also with a lot of tragedy. I think its an especially relevant story to tell to audiences in the West as its such a clear example of how Western politics and business have meddled with Africa, and how the economic growth of the west has come about as a direct result of that. I think its really important for all of us to learn about the people upon whom suffering has been inflicted for the West to become so affluent. Spreading awareness about things like that is a key step to making a change – just look at the success of the global effort to raise awareness about apartheid and the boycott of South Africa.

A while after I had started research for this project, George Floyd was murdered in the United States. In the mass movement which followed his death, I saw a huge re-assessment of colonial history – people like Winston Churchill who were once celebrated as heroes in their own countries were being put on trial for the atrocities they committed elsewhere. I knew then that my own motivation to engage with the history of Congo was not isolated, but had come about as a part of a global change in attitude. I think its a really good time for a book like this, which is aimed at a mass audience, as I think that the general public are currently much more perceptive to this kind of narrative than before.

Another major development during my research for this project was the coronavirus pandemic. Originally, I had planned to go to the Congo and write something based on the current environment. Obviously, with all the travel restrictions which came, I had to change that plan. The result was a book which does not present any new research, but rather aims to collect existing research and present it in a new and attractive format, which hopefully speaks to a wide audience.

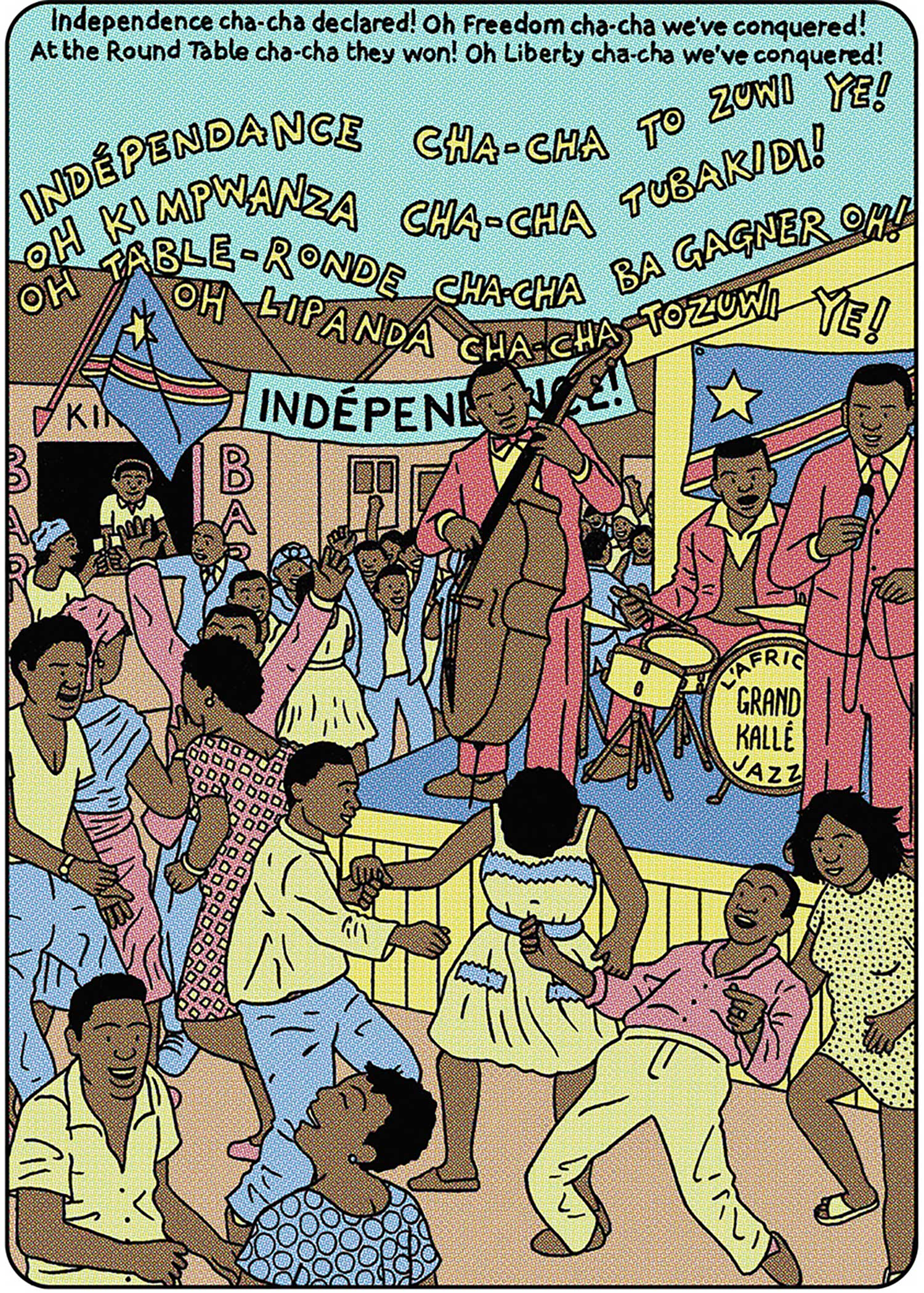

As well as highlighting inequalities, its equally important to celebrate the lives and achievements of the Congolese people, everything they’ve been through, and everything they’ve created from that. Time and again the Congolese have stood up en mass to defy the corrupt systems which have ruled them. Congolese women have bypassed sexist legislation to become leaders in local business, and Congolese musicians have changed the face of popular music across the continent. Basically they’ve got a culture every bit as rich as any other, and learning about it is a great exercise in celebrating the beauty and variety of human existence.

I like to tell stories which I would love to read, and in many ways my target audience is always people like myself – those are the people who’s experience I’m most familiar with. In this case, that’s Western audiences who are pretty oblivious to whats going on in Africa, but might like to learn a bit more – which I think is a hell of a lot of people. Up to now I’ve mostly answered your question by explaining how relevant this story is to that audience. It’s important to say that I would love for this book to bring something to audiences within Congo and the diaspora as well, and I think that it has the potential to do that. I wrote the book in English as it’s my native language, but I’d really love to see it translated to reach more Congolese audiences as well. That’s obviously a next step once the English version is already on the shelves, which will be in Autumn of 2022.

Your work is informed by the ligne claire style of comix- and I suppose I want to ask about Hergé’s early comic Tintin in the Congo and how that informed your thoughts about this project. Do you feel any push or pull against that work and the politics of that work with this project?

My thoughts towards Hergé are very conflicting, as I think they are for many of his fans. I’m sorry but I can’t really give a short answer to this question.

As you might guess, Tintin was one of the main comics which inspired me as a youngster, and made me want to go into comics myself. Hergé’s art style, far more than any of the other artists I was reading at that age, stuck in my head as the perfection of the comic style – the unnatainable goal which must always be aimed for. Scott Brown said that comics art is the art of simplification, and for me Hergé developed a style which arrived at that perfect level of simplification – easy to follow but beautiful in its depth. And after Hergé there was a whole movement of people like Jacobs and Swaarte who continued and even improved the style.

The problem of course is that Hergé’s works contain racist caricatures. It’s a bit of a weird one because he obviously loved Chinese culture and did a great job of celebrating it in Blue Lotus, but his depiction of black people was pretty disgusting throughout his career. Tintin Au Congo wasn’t reprinted in a lot of countries for a long time because it was so offensive. People often excuse Hergé by pointing out that he very young when he made that book, and that he wrote it under instruction from the publisher of the newspaper. It may be true that such a young man, who had been brought up in a country which celebrated colonisation, didn’t know any better, and I think we could empathize a little with Hergé for that, as it takes time in anybody’s life to re-examine the mainstream viewpoints which surround us culturally. But that argument doesn’t hold up very strongly when you read a book like The Red Sea Sharks, which he produced much later in his life, when his career was already well established. The African characters in The Red Sea Sharks aren’t drawn in such a grotesque caricature as those in Tintin Au Congo, but he still depicts them as simple, irrational and basically savage. And that book was never banned or taken out of publication. It’s especially dangerous because these books are mostly read by kids, many of whom will just accept the characters at face value, and those characters will go on to formulate their view on the types of people they depict.

Tintin Au Congo wasn’t actually printed in the UK until I was about 15, so I’d already fallen in love with the series by the time this bizzarre relic came to the surface for me. When I read it at that age I could understand that the sort of Gollywog-style depictions of the Congolese characters were incredibly offensive racist steriotypes, but the finer details of how wrong the whole thing was were quite lost on me. We hadn’t been taught anything about colonial history in school and I was, like most of my contemporaries, still incredibly ignorant to what had actually happened during the colonial period. But I had some dim sense that behind this comic lay a dark story, and a curiosity was sparked in me which lay quite dormant within me for many years, but I suppose that curiosity was the very beginning of my journey towards making Postcards From Congo fifteen years later. It was the curiosity to find out what was the true reality which lay behind this obviously vastly misrepresented reality, which was Tintin Au Congo. I think one of the things which spurred me on to write this book was that I had a feeling that the Congolese had been given a really unfair write-up by European comics, and that I sort of feel like they deserve more of a fair and balanced depiction. I really hope that this book can play a small part in counter-acting that ignorance which I and so many others have held towards colonial history, as well as modern African history.

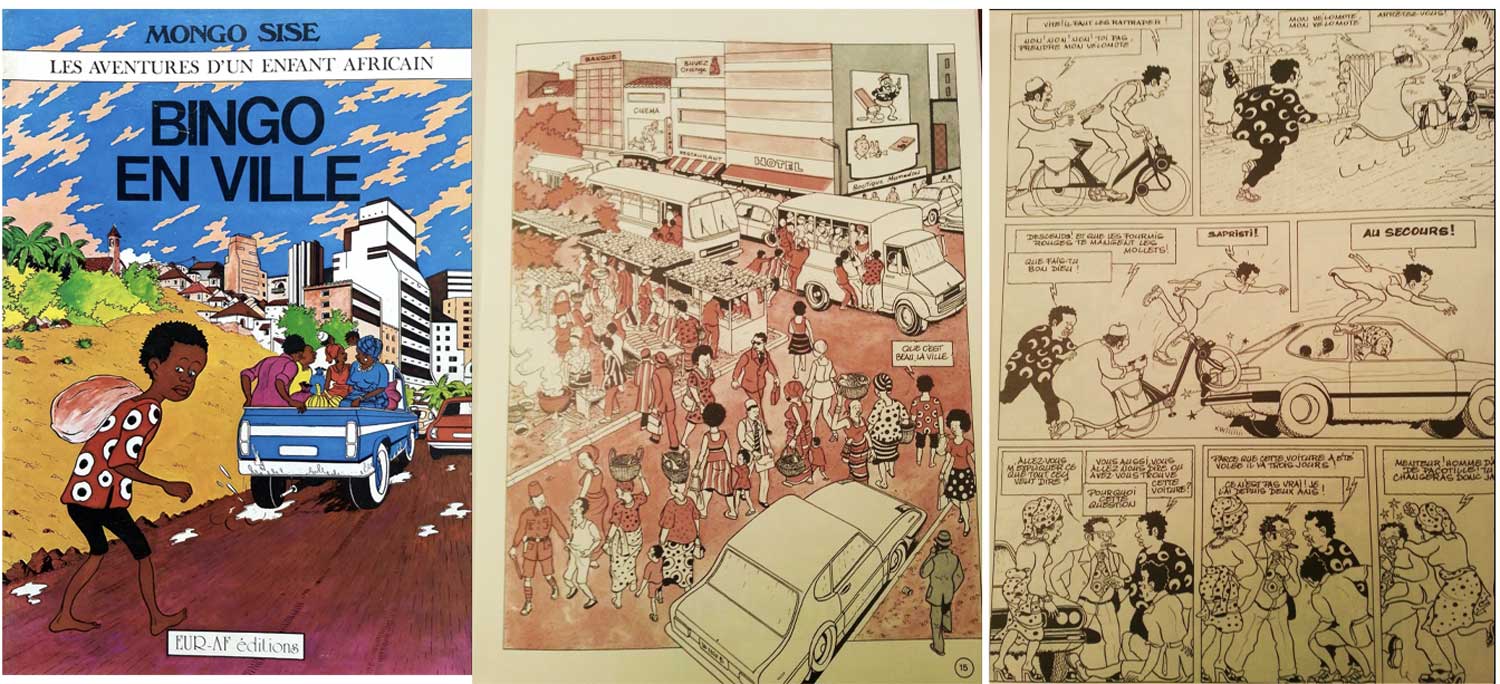

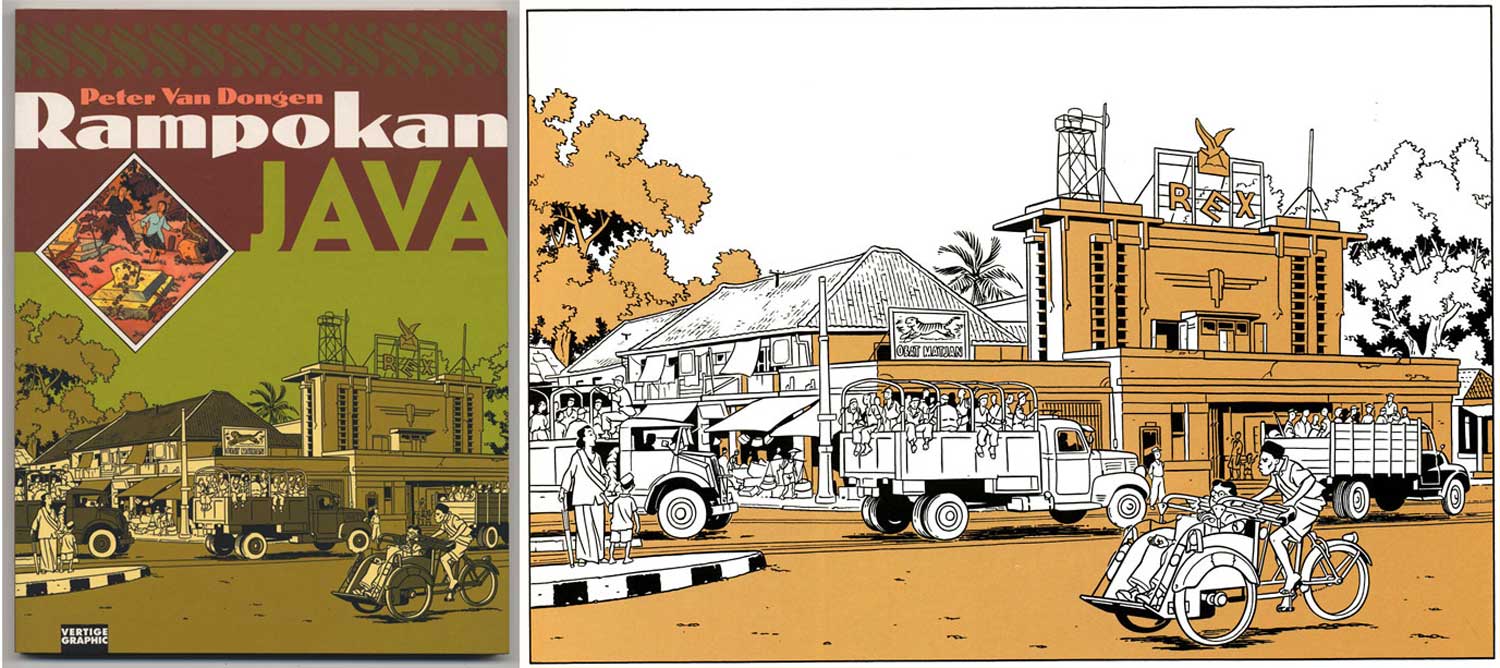

Its also worth stating that I’m totally not the first person to re-visit the Congo in the context of a Ligne Claire style. There’s a great Congolese comic artist called Mongo Sisé who was active in the 70s and 80s who was also heavily influenced by Hergé, and he actually went to Hergé’s studio to study under him for a while. He’s got a series about a boy called Bingo which could definitely be interpreted as a Congolese cousin of Tintin. Sisé totally flipped Tintin’s African voyage on its head and sent Bingo to Belgium in Bingo En Belgique. I’m also not the first person to provide a critical view of colonial history in the context of Ligne Claire. Peter Van Dongen probably does a much better job of it in his masterpiece Rampokan, which looks at the Dutch colonization of Indonesia

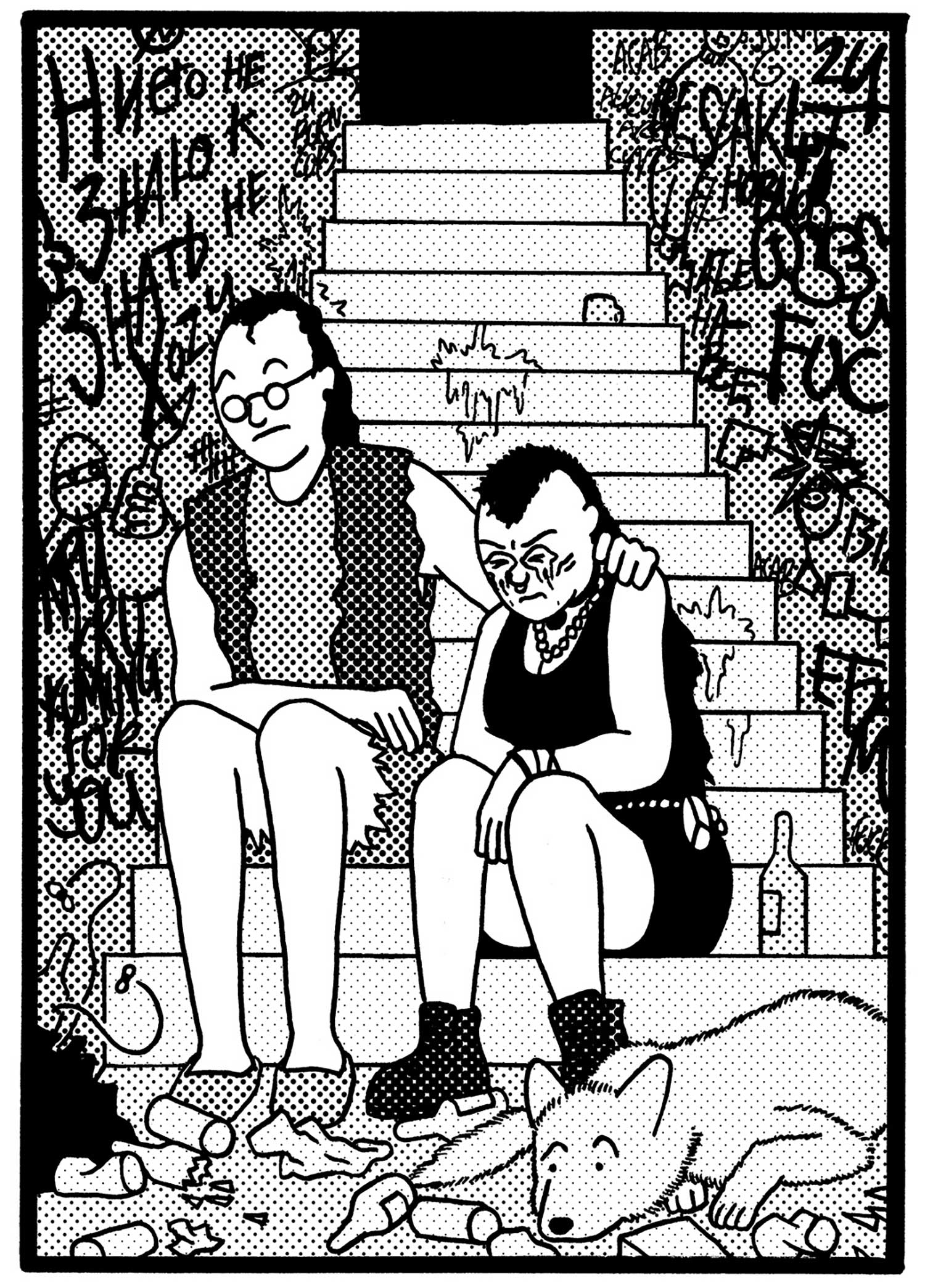

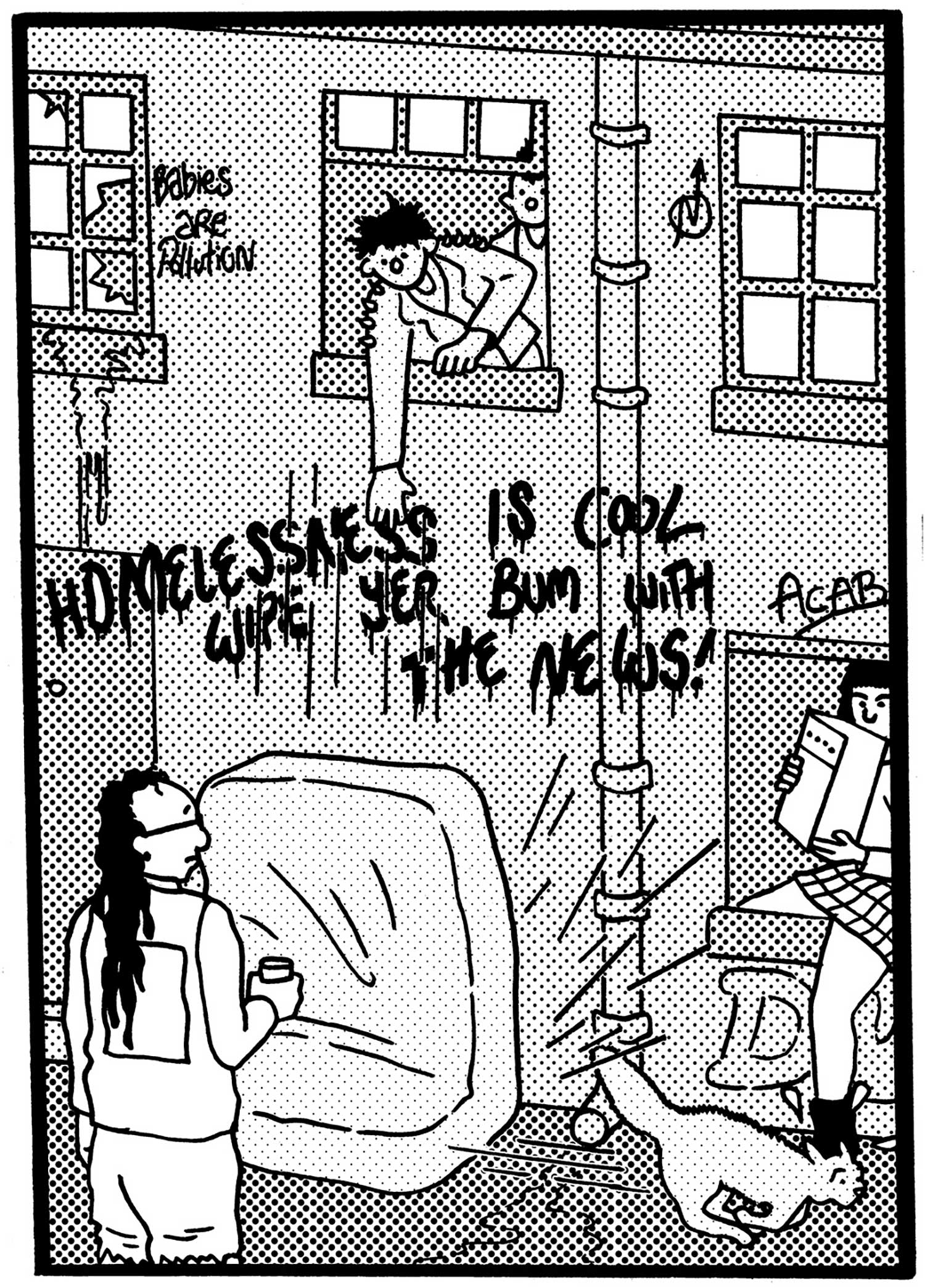

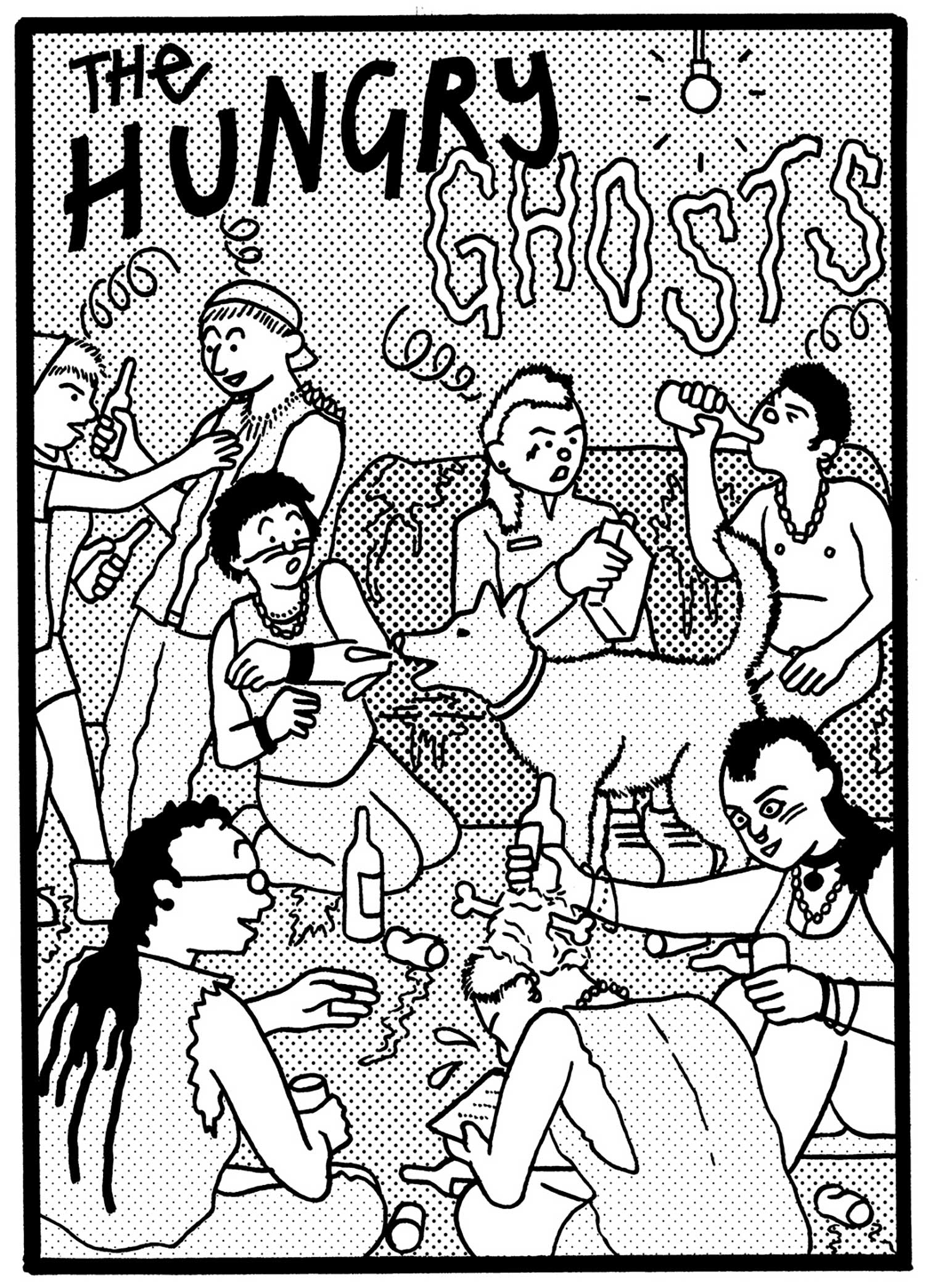

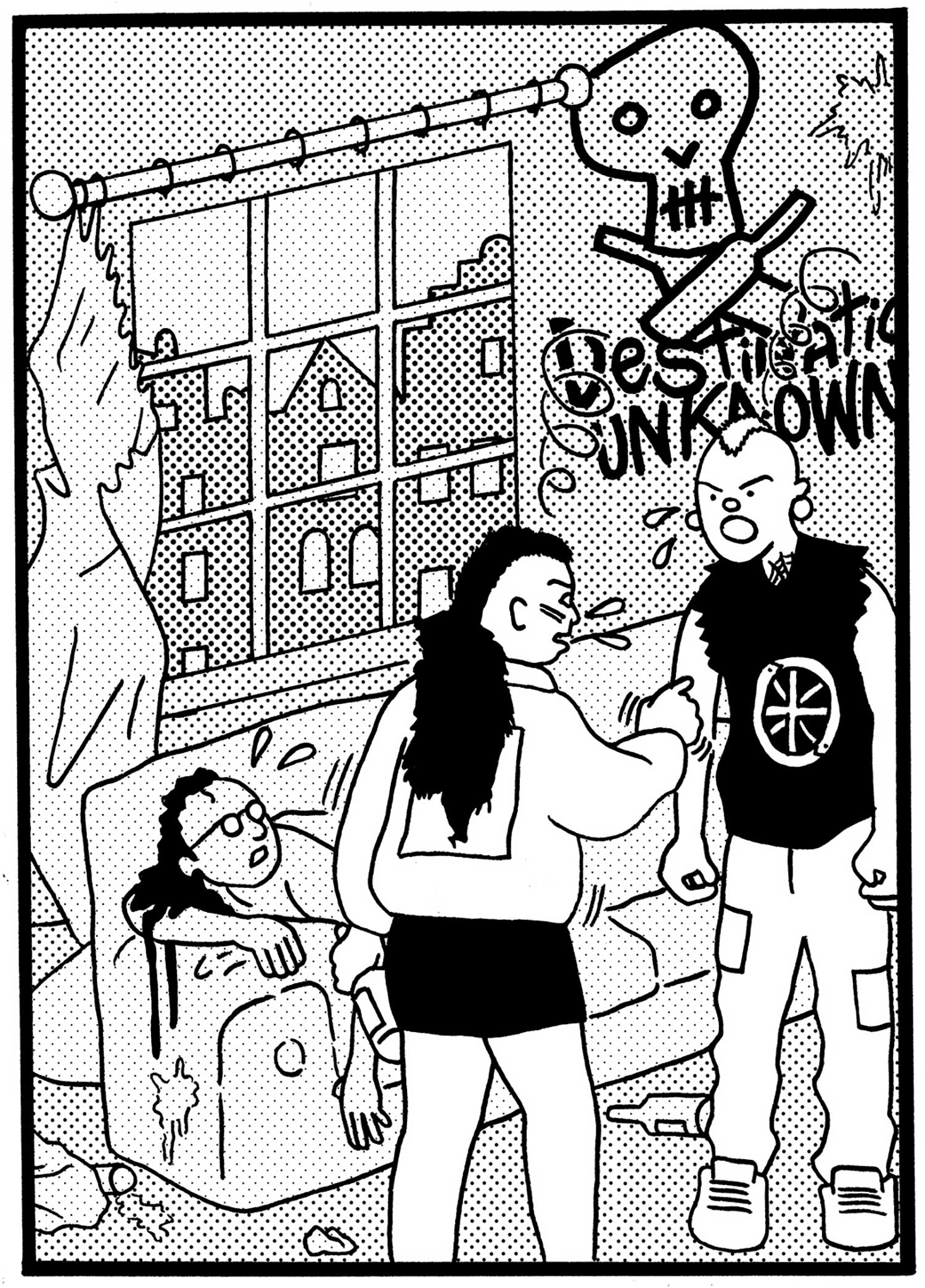

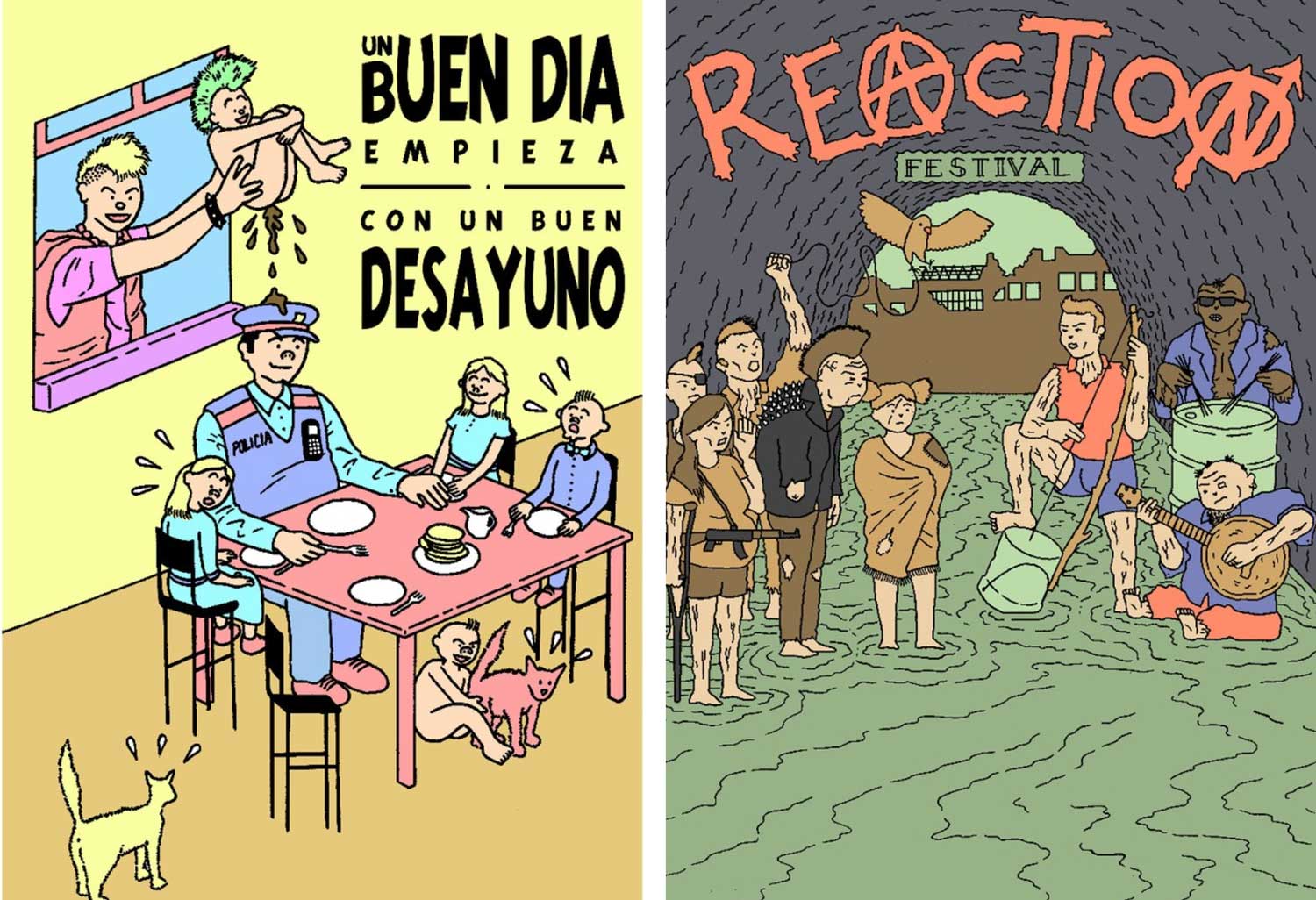

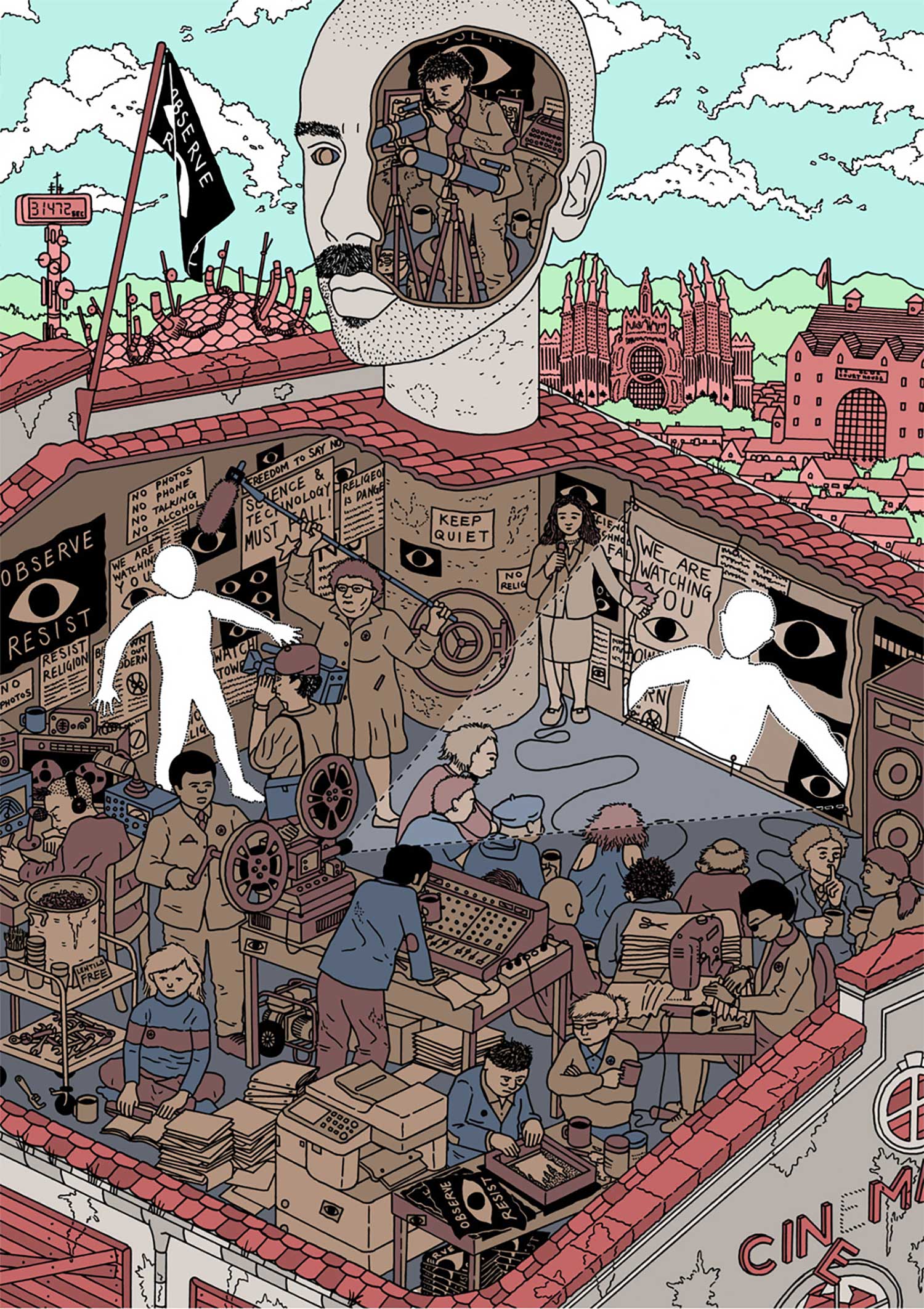

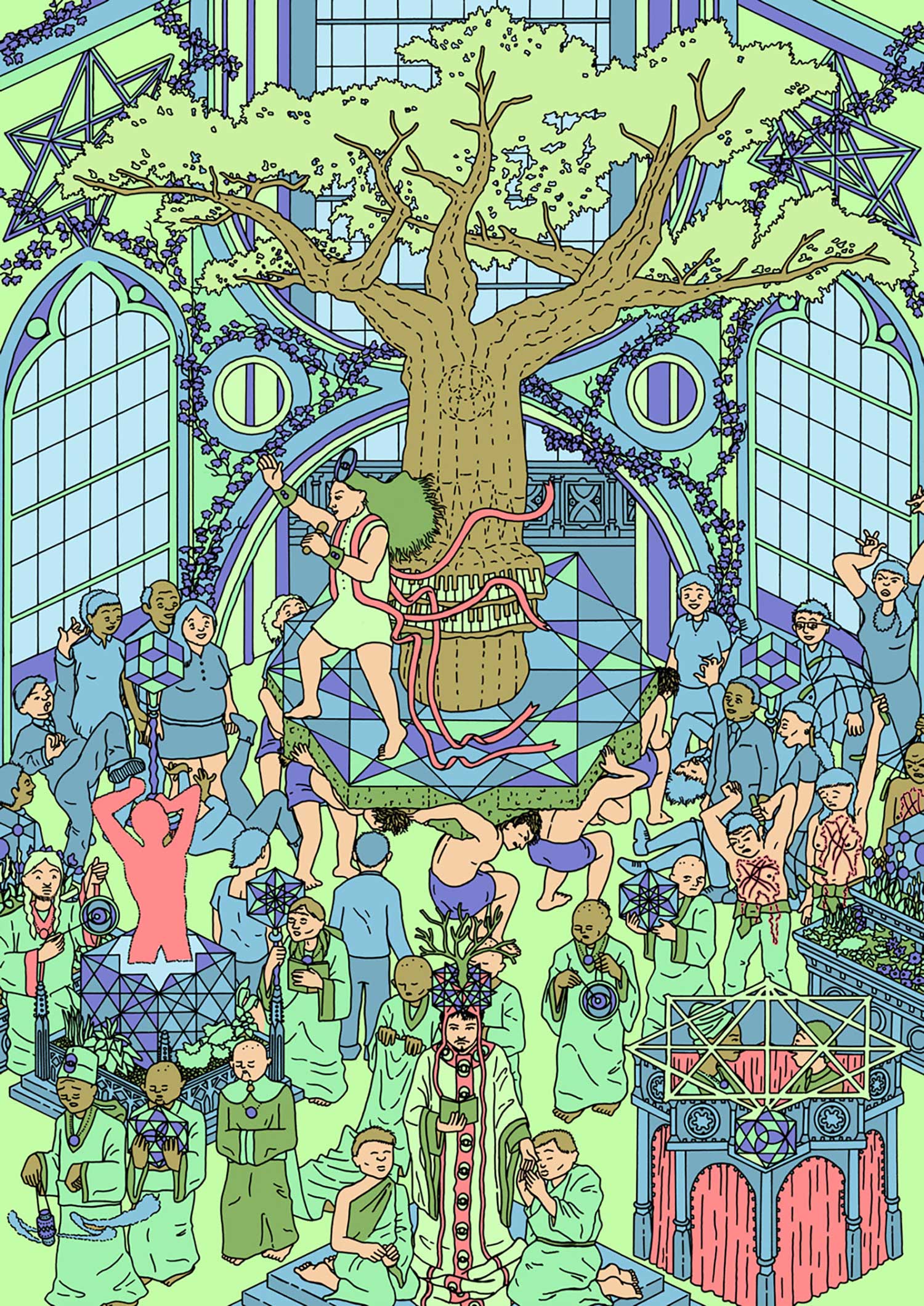

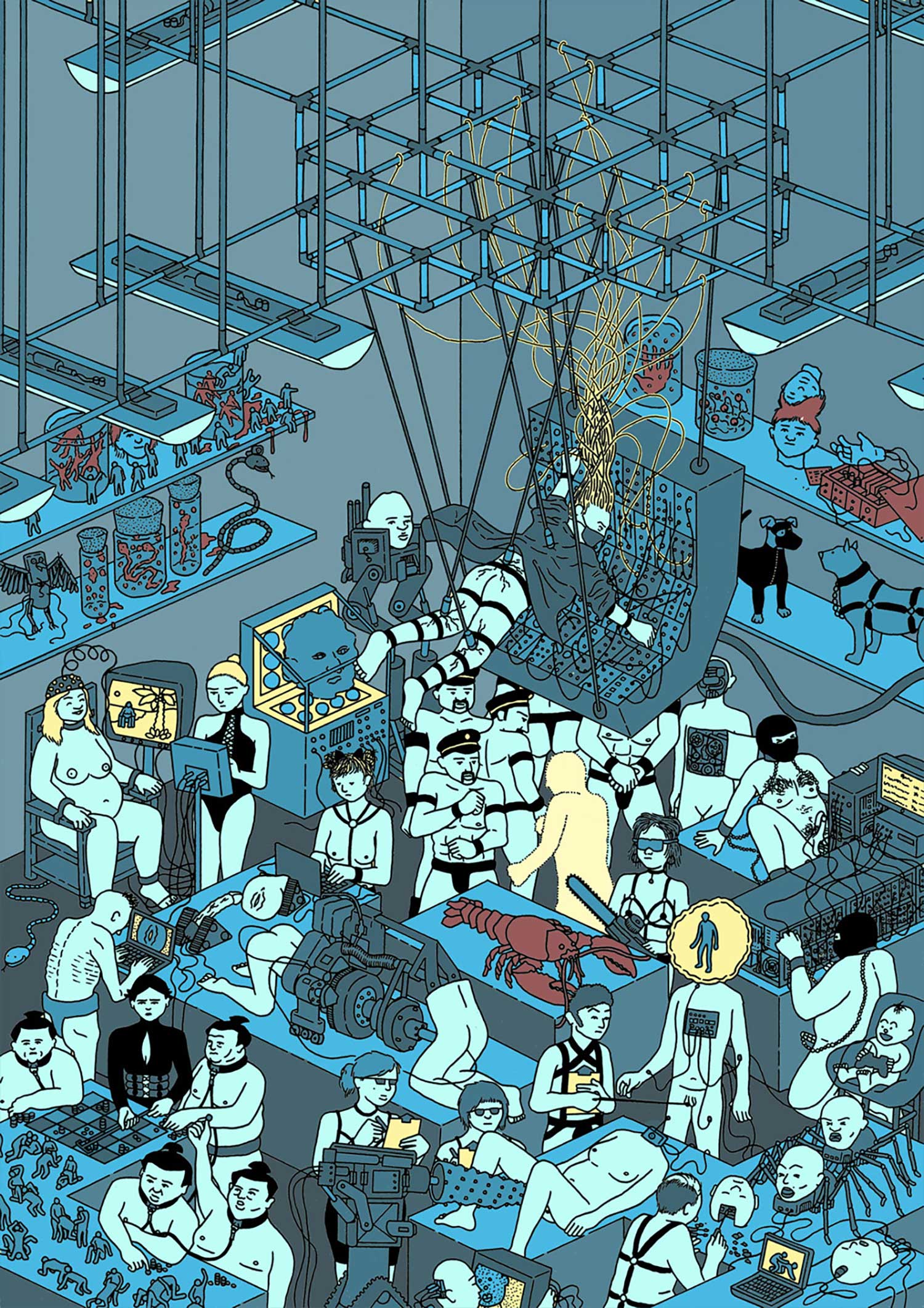

Obviously one of the reasons that I like to draw in Ligne Claire is that I grew up reading comics drawn in that style, and I think it’s a really beautiful style. But I think the reason that I’m really stuck on that style, and that I think that style works really well for the kinds of stories I drawn, is that it’s a style which has a lot of connotations attached to in, and I love to illustrate scenes which have a great juxtaposition to those connotations. For example I think a lot of people associate Ligne Claire with an earlier, more innocent and family friendly period of comics, so I love to use that style but draw images which show a grittier side of life. I made some illustrations to accompany a great book called Good Times In Dystopia, which include scenes of the protagonist having drunken arguments with his girlfriend, breaking in to buildings, and even masturbating. I think that those images have so much more punch to them because we expect this familiar drawing style to show us something which is innocent and playful, so we drop our guard for it, but the image we find is anything but innocent- it’s a re-appropriation of a classic style!

Because of Tintin Au Congo, one of the association’s which a lot of people would have with Ligne Claire is colonialism, specifically Belgian colonialism. What Peter Van Dongen was doing in Rampokan, whether he intended it or not, was using this style which we associate with a celebration of colonization and turning it on its head to present a critical and more realistic view of colonization. And I hope that Postcards From Congo can have a similar effect. That’s basically why I chose to continue using that style for this project.

Hergé is still a huge influence on me, and I still love to revisit Tintin books, but as with many of our favourite artists we have to accept that he was a flawed person who did some things we strongly disagree with. Rather than ignore all of their work on the basis of those flaws, I think we should use them as a platform to discuss those issues and learn from the mistakes of those artists.

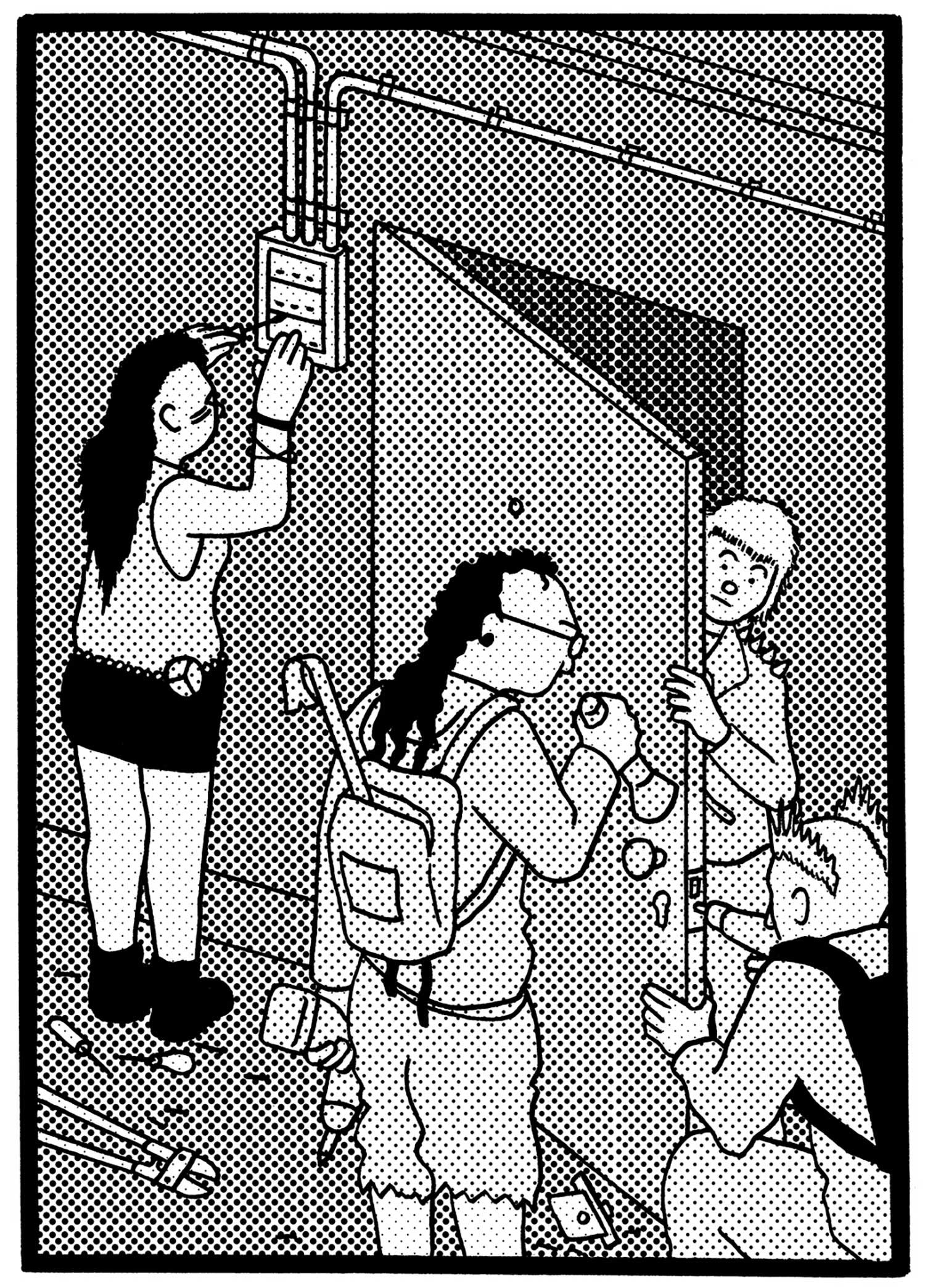

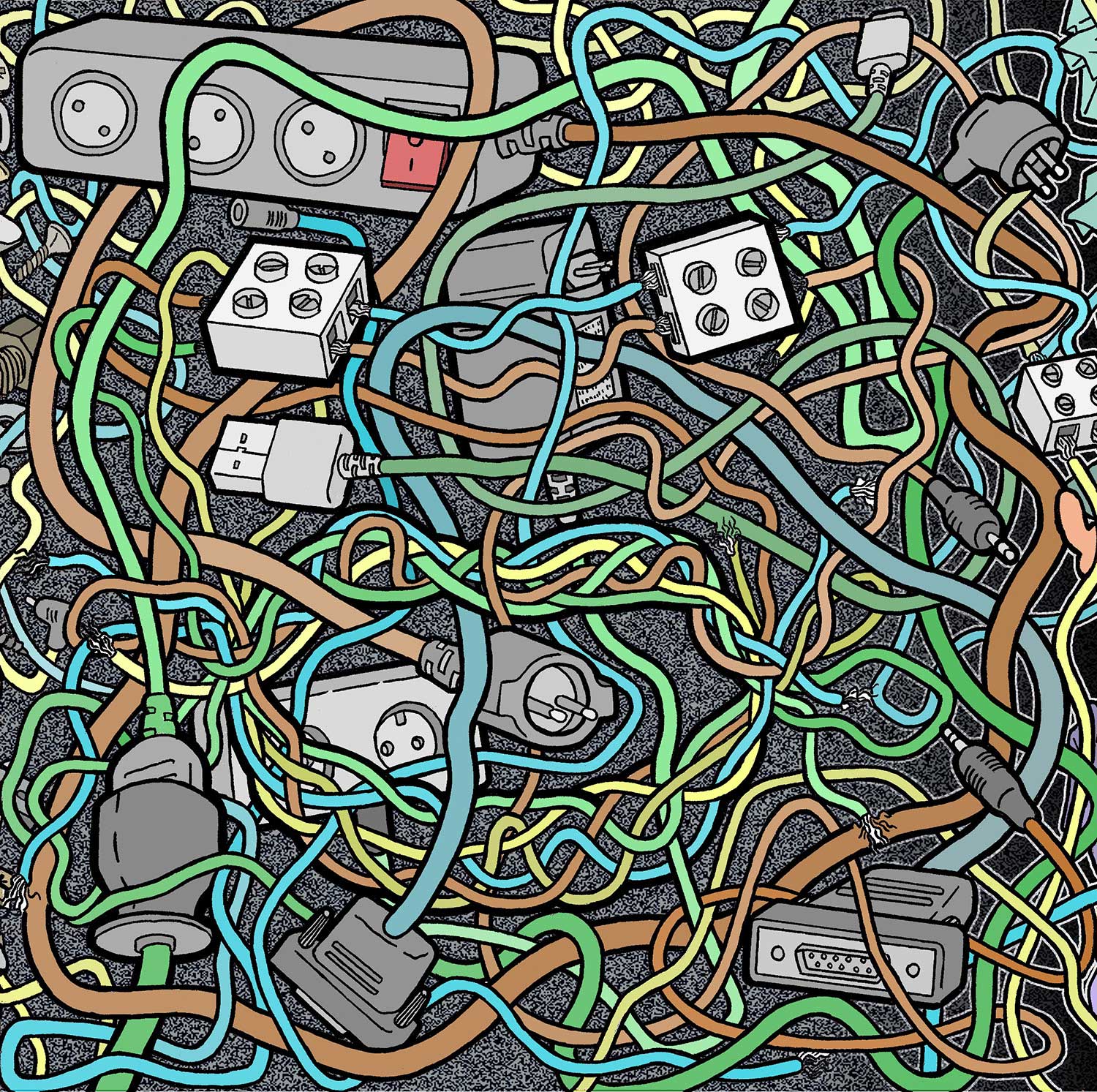

Can we walk through one or two images- I’m hoping to find two pieces with very different approaches- so let’s say the image from Postcards From Congo of the Grand Kallé Jazz band playing and one of your more abstract works- like the one of all the cables and electrical cords . How did you go about composing these works? What is your process like? Does your process differ from the more documentary work of one and the more playful nature of the other?

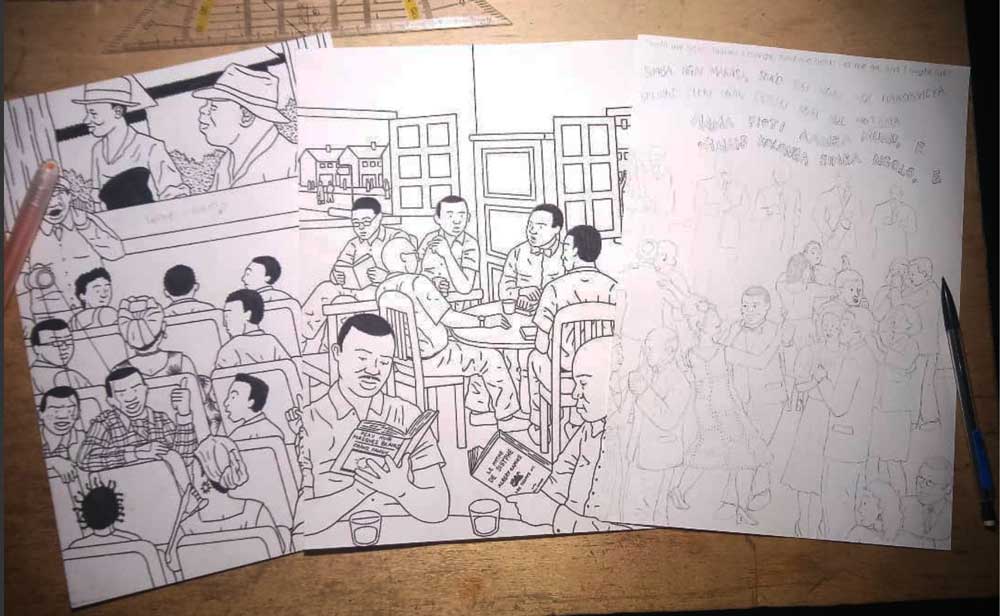

I always start my drawings by sketching out what i call the ‘skeleton’. Basically i use a pencil to do a rough outline of everything which will be on the page, and i keep erasing and re-arranging things until i get a composition which I’m happy with. The ‘skeleton’ is just a really rough sketch of outlines and stick-figures, but its enough for my imagination to fill in the rest and make sure that I’m happy with the composition before i put in all the hours of filling in the fine details. Sometimes I get the right composition on the first try and I don’t have to rub anything out, sometimes I’ll sit with the page for more than an hour trying out different possibilities until I get something I’m happy with. Making sure that I’m happy with the skeleton before I go any further means that I’m pretty much always happy with the end result when I get there.

Once I’m happy with the skeleton, I just move through the drawing, feature by feature and draw it out in more depth and detail. I use a lot of photos as a reference to make sure things look how they should do, especially with the historical stuff where small details like clothes or hairstyles or posters on the wall make a huge difference in the atmosphere of the final product. I draw it all out in pencil until all the details are filled in, and when I’m happy with it then I go over it all with ink. It’s a bit of a slow technique but when I rub away all the pencil I get a really clean and clear finished drawing, which is what I like.

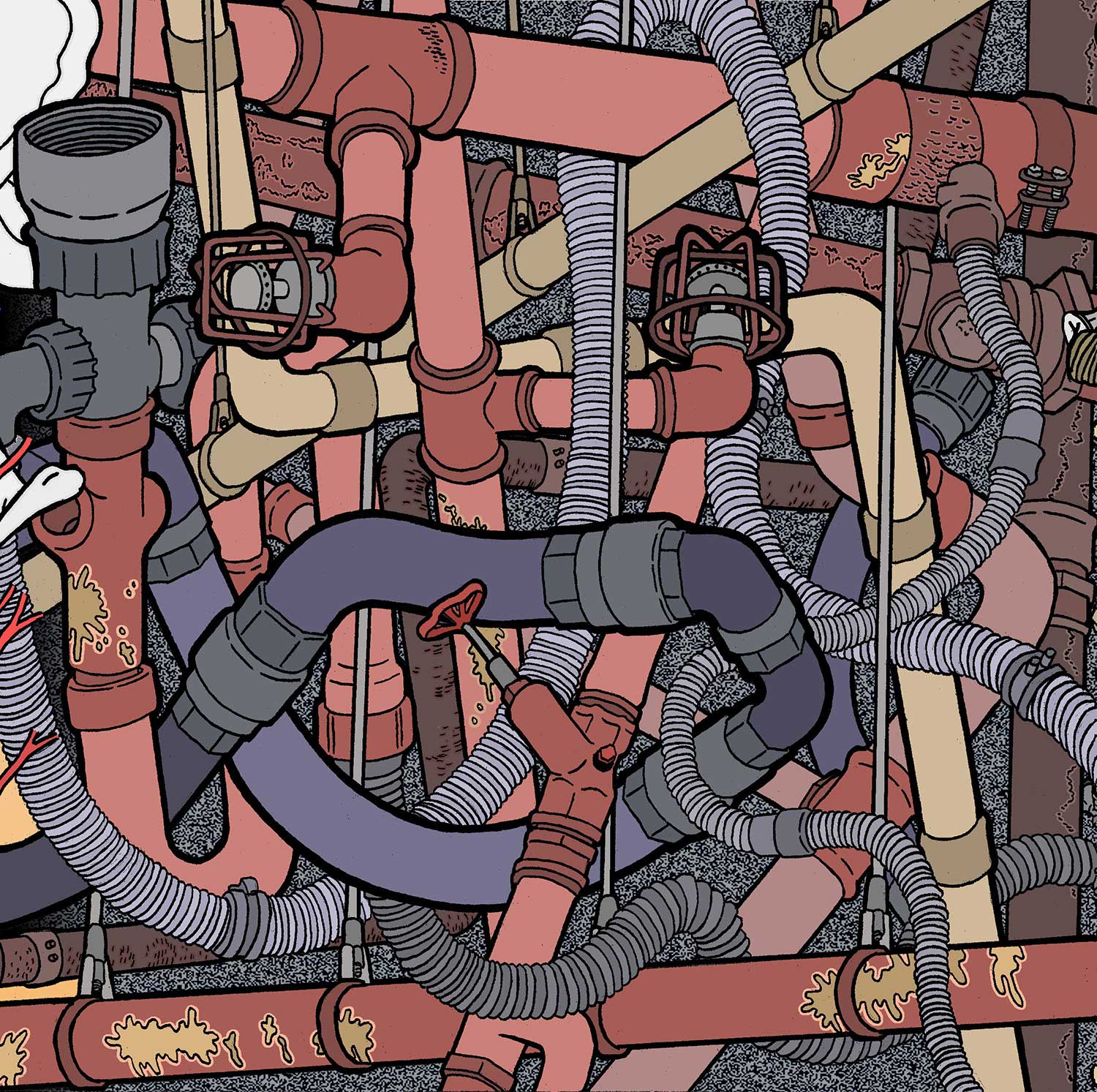

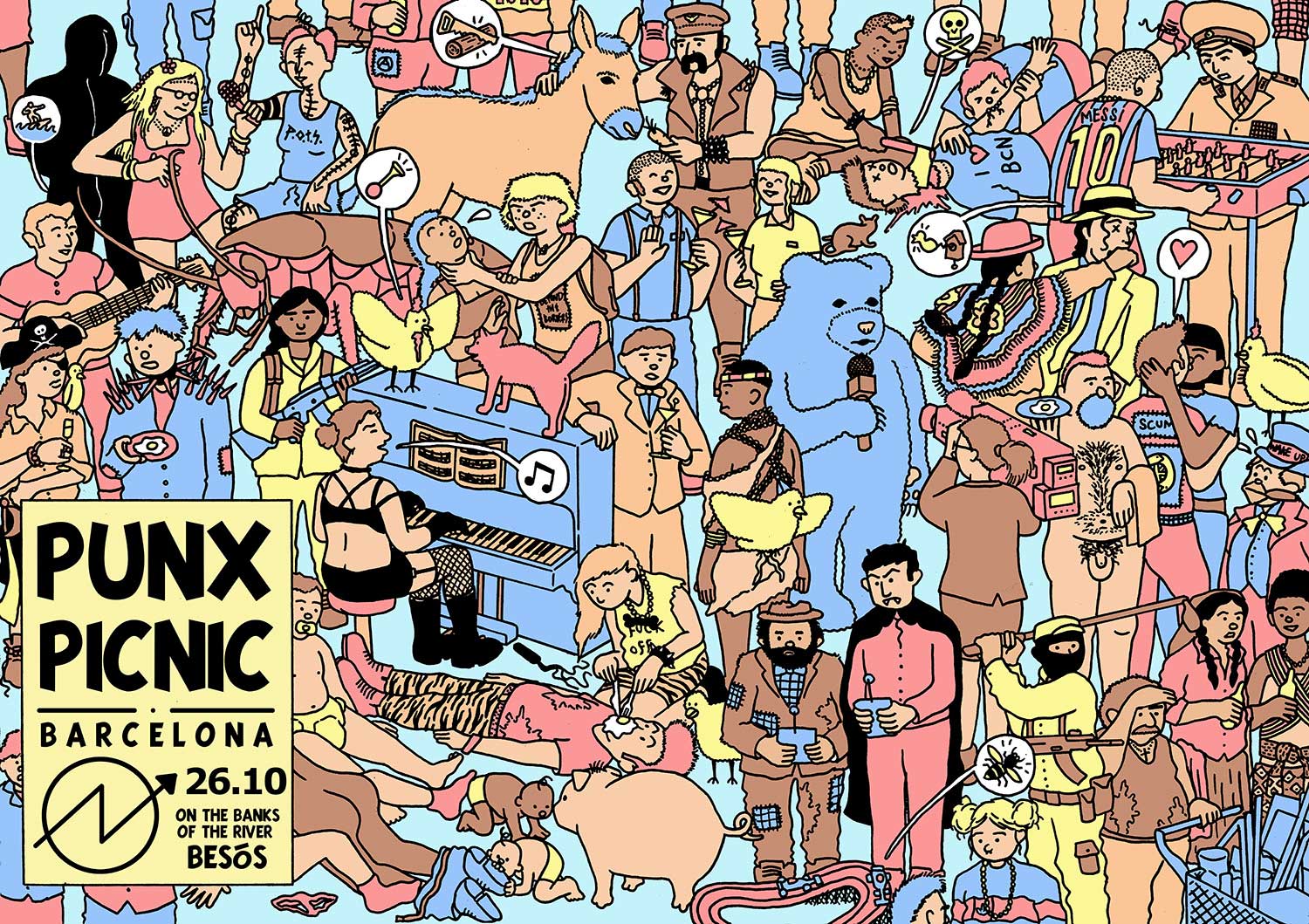

The two drawings you mentioned in your question come from about seven years apart, so the difference in style comes mostly from a difference in what I’ve been interested in drawing as time has gone on. But they are both examples of a common visual theme which has always been in my work, which is that I just love chaotic images of jumbled up stuff. So that used to be big knotted piles of cable, or plastic bags, or organs… now its busy images of crowds with lots of things happening. I call them my ‘Where’s Wally’ images, because they’re quite inspired by those books – there were always so many funny things to find in those images.

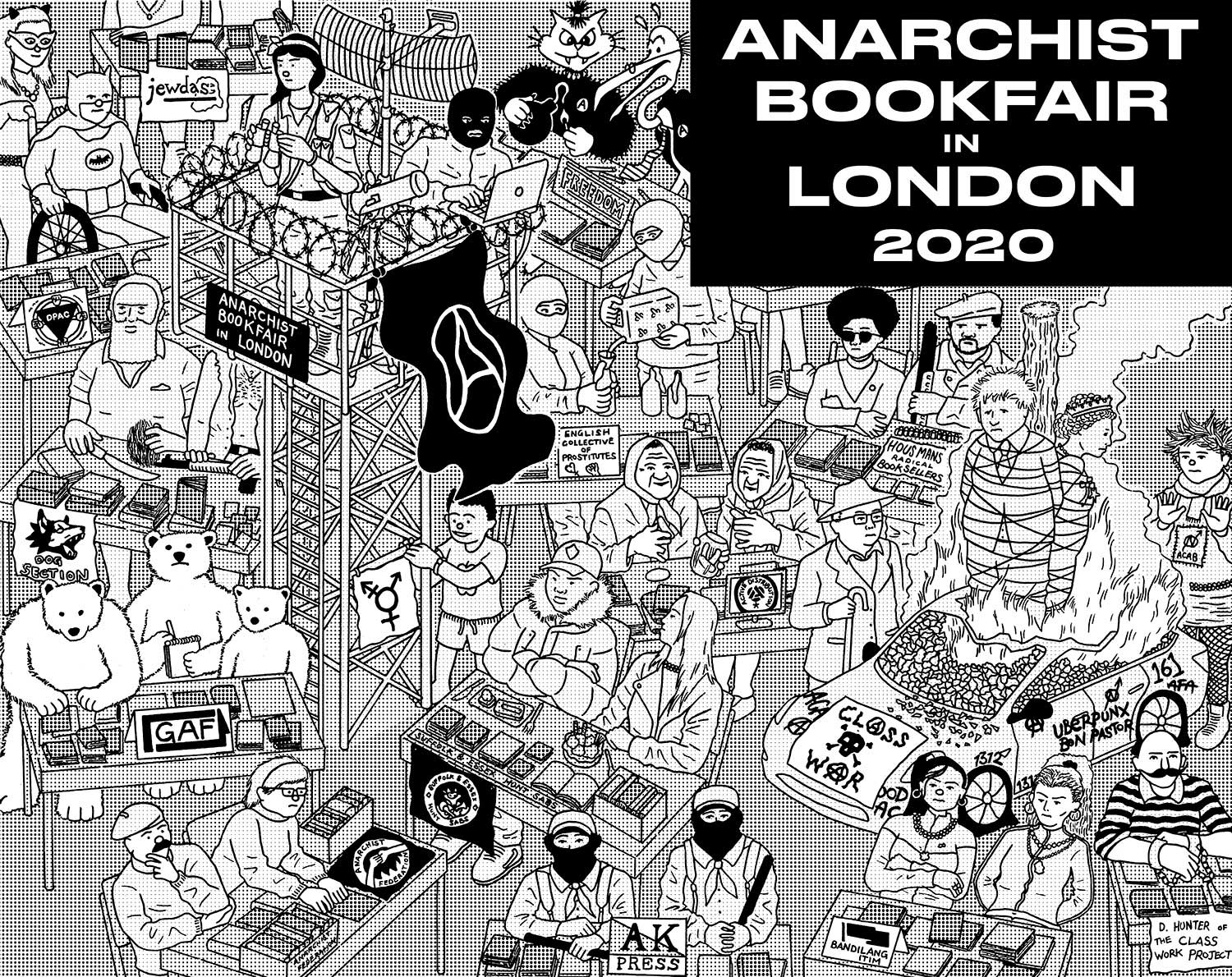

I love all of your detail and all of the small bits of humor in your work, especially in some of the bigger busier pieces (the punx picnic graphics, the anarchist bookfair, etc). How much of that work is deliberate and planned out ahead of time, and how much is improvisational?

Usually for those ‘Where’s Wally’ images I just write down a big list of ideas for things that could be going on in the scene before i start drawing. Sometimes I talk with whoever’s around me and brainstorm some ideas. Then I put all of those ideas into place when I sketch out the ‘skeleton’ of the drawing. Usually a few new ideas come into my head as I’m sketching everything out, and I’ll try and rearrange things to work them in there. Usually those spontaneous ideas are some of the best ones because they appear out of nowhere, straight from your subconscious – direct from the source!

Aside from instagram- how do you get your work out there? Do you have published comics that people can find?

I used to do everything ‘In Real Life’; i.e. self-publishing the comics and selling them at concerts and festivals, basically because I felt like we all spend too much time looking at screens anyways, and it’s nice to enjoy things which we can touch and smell and put on our shelves to show to friends when they come over. I’ve slowly had to come to terms with the fact that I was born a few decades too late, and that’s considered a pretty old school technique these days. A lot of people aren’t really receptive to it, so at the moment I’m trying to get to grips with promotion via social media.

I don’t have an online shop, but if anyone wants to buy any of my comics or prints then they can send me a message on my Instagram (@junk_comix) and we can work something out. The main thing I’m promoting at the moment, which is currently in print, is Dunkirk Jungle which was a collaborative work between a few of us who were on an aid mission in the Dunkirk refugee camp last year. You can read a bit of it on my Instagram, and if you want to buy a hard copy then all the proceeds go to future aid missions to that camp.

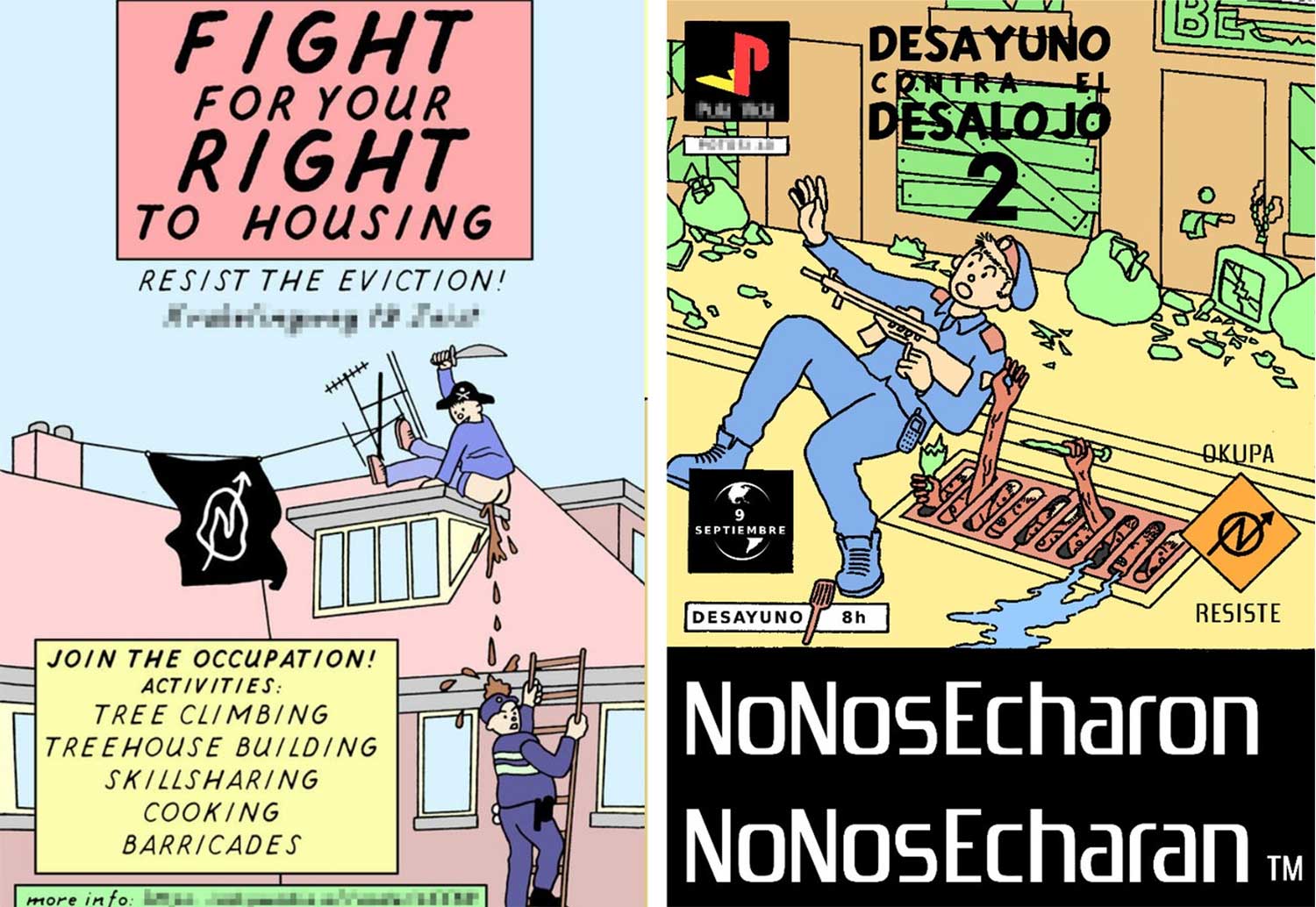

Comix and squatting have a long relationship with each other- in informational guides, graphics, and in stories… I’m not sure if I have a question here! But I see a long shared history that is mostly uncelebrated. You use humor and images for information, inspiration, celebration, and critique about squatting and liberatory spaces, and I suppose that there’s a history to this. Does this ring true to you? Did you find squatting and comix together?

Squatting can be a really great thing to do if you’re an artist because it does mean that you don’t have to worry too much about making money. I’ve been able to spend years creating work which was interesting to me, and not having to worry about making a living from it. I didn’t go to an art college so that was basically my development process. Starting out by spending years making shit is just a necessary thing to go through as an aspiring artist. So as a result of that a lot of artists are drawn to squatting and the movement has always had a really strong creative and visual aspect to it.

In terms of what you said about humour, I’m a big fan of Gilbert Shelton’s Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. I think one of the best ways you can celebrate your own subculture is by taking the piss out of it. It’s important not to take yourself too seriously or nobody on the outside will be interested. So that’s something I try and incorporate into my work.

To be honest, I don’t see that many comic artists around in squats at the moment. When I started squatting I had this utopian dream of finding the crew of squatter comic artists and opening a place all together, but so far that hasn’t materialized. If you’re reading this and you’re a comic artist who squats or is interested in squatting, then send me a DM!

Will you tell us about some of your comics reportage work concerning migrants and migrant camps in Europe?

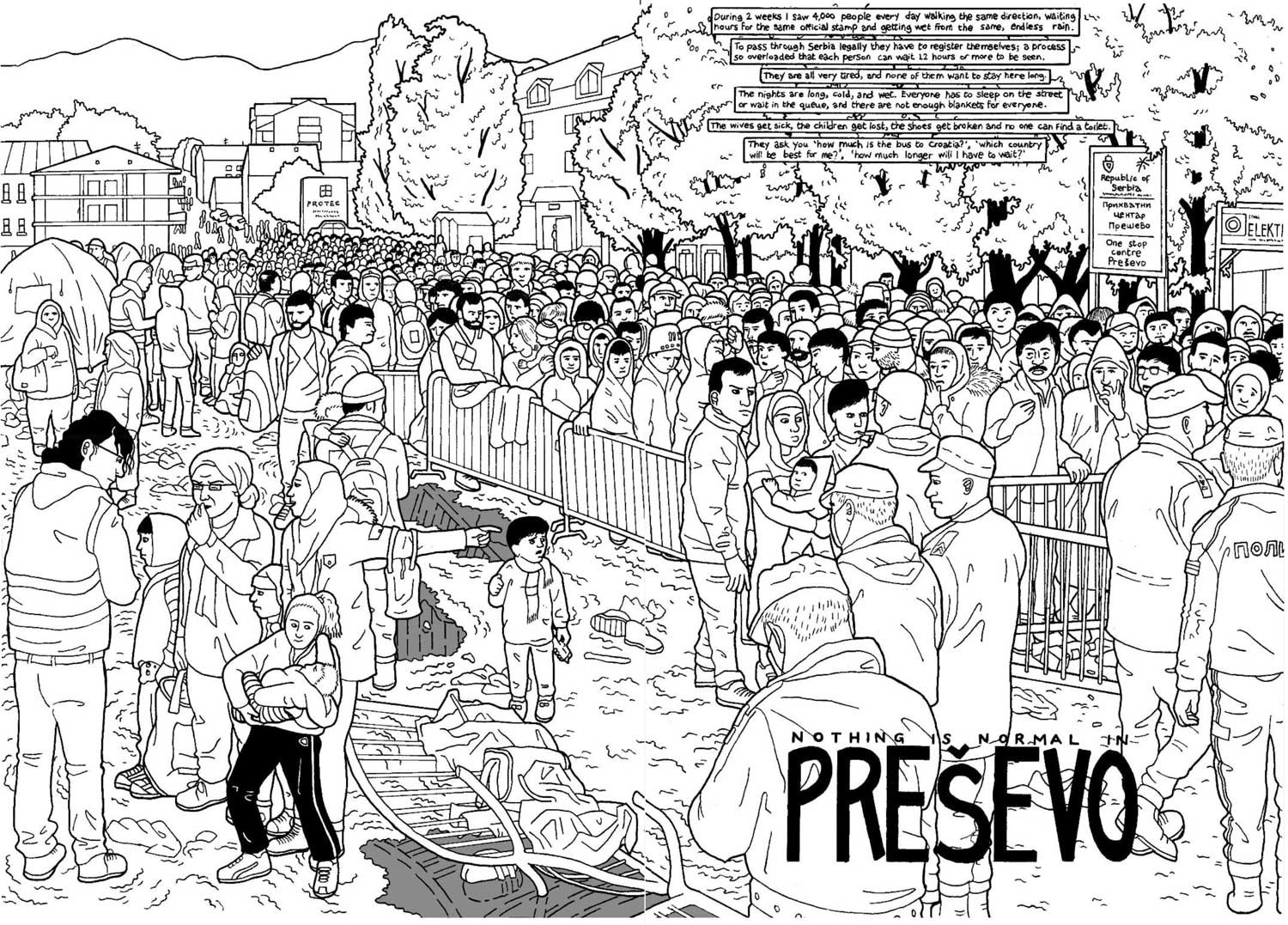

I’ve made two comics based on my experiences in migrant camps in Europe. The first one, Nothing is Normal in Presevo, was written during the big wave of migrants coming from the Middle East in 2015. It’s a non-fiction work and it explores the background of three of the ethnic groups who were present at that camp in southern Serbian, two of the migrating groups as well as the locals.

The more recent comic is Dunkirk Jungle which I mentioned above. Basically we were on an aid mission in Dunkirk, and while we were there Alejandra (@knopfabriek) started inviting some of the migrants who we were friendly with to do interviews about their stories. Together we wrote a fictional story from a composition of each of their experiences.

Who are some comic artists (living or dead) that have inspired you?

Chester Brown’s Louis Riel really showed me how well history can be dramatized within comics. Brown’s work also showed me how a comic can have a very regular panel structure without sacrificing any of its charm, and in fact making it easier to follow. All his panels are the same size, and every page has the same layout. It allows the artist to edit like a film-maker would – cutting out or inserting panels.

Joe Sacco was a huge influence. Everything about his work is amazing – the research, the artwork, the storytelling, I love his gonzo style! He showed to the English-speaking world that comics could be a really serious art form and a great medium to share information. I wish that process could continue a little and English language readers could all just wake up from this surreal superhero-obsessed world and see the true potential of comics, which has already been unlocked in so many other languages, especially French and Japanese!

Li Kunwu and Philippe Otié’s A Chinese Life (2012) was another work that really opened up for me how well comics could be used to record history. Like Sacco’s work, it has a really personal spin on it – the perspective of the narrator plays a big part in how the history is told. Basically it’s just an autobiography, but it’s an autobiography of a guy who’s life was intertwined with the development of communism in China, so it tells that story from a really personal perspective. And it’s so refreshing to hear a Chinese voice giving their take on China. There’s so much in the media at the moment about China, but almost none of it is coming from Chinese people! He’s got a really interesting take which in neither fully anti-CCCP, nor fully pro-CCCP – he presents the good and the bad together, as he perceives it.

Visually, I love the work of Vittorio Giardino. Giardino drew in a kind of Ligne Claire style, but with much more detail than Hergé. His narratives had much more depth than Tintin stories, and were aimed at an adult audience. Still, they were obviously inspired by stuff like Tintin and the Blue Lotus, as they use the medium of detective-adventure stories to tell the reader something about a certain moment in history.

Anything else you want us to know?

Postcards from Congo is coming out this Autumn, and will be published by Arsenal Pulp Press, and it will be available in bookshops and online. If you want to keep updated about it or if you have any questions then follow me on Instagram!

Also… I’m planning to visit Congo later this year. I want to learn Lingala and continue on my journey of exploring Congolese culture and history. If anybody reading this is Congolese, or has friends or family in Congo, and would like to meet me to have a chat while I’m there, then please send me a DM on my Instagram!

Signal: A Journal of International Political Graphics & Culture is the collective project of Josh MacPhee and Alec Dunn. All copies of Signal are available for sale here on Justseeds.

Interview conducted via email in January, 2022.