Artist Garrick Imatani has been working on a series of powerful projects related to culture and power in the context of colonial and Indigenous relationships to land, and to the expropriation of Indigenous tools and artifacts by the museum. His recent work has at its heart one of the most powerful objects in all of North America- Tomanowas, the Willamette Valley Meteorite. Garrick is Assistant Professor of Sculpture and 3D Fabrication at Southern Oregon University with dual appointments in the department of Art and Emerging Media & Digital Arts, and was gracious enough to answer some questions about his work and thinking.

You’re working on a to-scale reproduction of Tomanowas, the Willamette valley meteorite. Can you tell me how the project got started and what it consists of, who it involves?

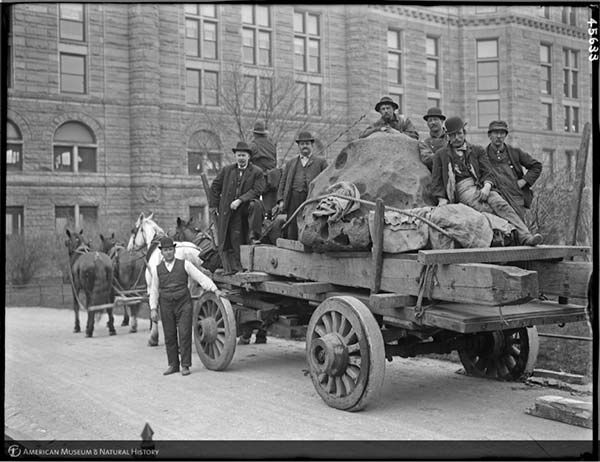

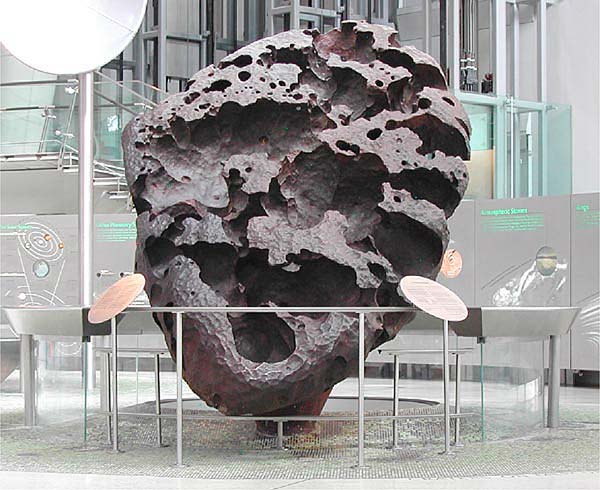

Sure. The project came about through researching a public art commission I got at the University of Oregon. As it’s my first permanent installation, I started thinking about the history of public sculpture and how its tied to the history of the public monument, which holds out the promise that an object can commemorate group values, or memorialize a specific event, etc. However, this approach just doesn’t make any sense within the context of a 21st century college campus or any public work for that matter, because the public is too diverse to coalesce around something so unstable as shared cultural value. So I started by thinking on a timescale that was beyond an academic context, and in looking into the geologic formation of the area, I came across the story of Tomanowas, or the Willamette Meteorite. The meteorite landed in either Montana or British Columbia and floated down on a massive glacier during the Missoula Floods about 13,000-15,000 years ago. This glacier dredged through the landscape, carving out the same valley in which Oregon’s largest cities are now situated, Portland and Eugene. Once the glacier melted and the water receded, it created an incredibly mineral-rich land, which in turn drove western expansionism and the forced removal of tribes off their ancestral land by the mid-1850s. In 1902, the meteorite was rediscovered by settlers and it became an instant sensation as it remains the largest meteorite ever found in North America. By 1906, the meteorite was sold to a NY socialite who donated it to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) where it still sits to this day.

However, the Clackamas tribe (now part of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde) regard the meteorite as a sacred cultural object and had sought to get it back through repatriation efforts for years. In the early 2000s, they abandoned this effort after the AMNH signed an agreement to let the tribe conduct private ceremonies with Tomanowas each year inside the museum. Plus, the museum had anchored the meteorite into its foundation and built walls around the meteorite. Last year, I accompanied the tribe on their annual visit to the museum, worked with their students to shoot hundreds of photos of the meteorite, and then used photogrammetry software to stich the images together and make an exact 3d model of the meteorite. Then, this summer the model was 3D printed (after I passed it through a tessellation algorithm) and these 3d prints were then slurried and cast in aluminum.

This aluminum sculpture will be chromed and hung in a building on the university campus, alongside a series of photographs and a wall work that was made with data from a GIS cartographer that used LIDAR (laser infrared scans) of the Willamette Valley from an airplane to show what the region would have looked like during the time of the Missoula Floods. For example, Portland and Eugene would have been completely submerged under water. The photo series was shot in conjunction with the tribe and serve as visual responses to the many archival images that document the historicization of the meteorite within a western model of scientific discovery, inquiry and novelty. For the photos, I had an exact to scale replica of the meteorite CNC-milled out of foam for us to restage images and in many ways the process was part documentary as I was more interested in asking: how do these historical images of the meteorite make you feel and how do you want to respond?

You have another project involving scanning and printing artifacts, can you say something about that? Who are some of the key people and groups that you’re working with?

Travis Stewart, who is also an artist and staff member at the Chachalu Museum at the Grand Ronde, has been instrumental in making the current project I just described happen. I was telling him about how there was a tribe from southeastern Alaska, the Tlingit, that worked with the Smithsonian Museum a few years ago to use 3D fabrication technologies to replicate a ceremonial hat. After having the hat repatriated back to the tribe, they wanted it replicated so that it could be on display in lieu of the original. Within the last few years, the Smithsonian has been better than many museums in terms of repatriation efforts but it made me think how one could use these technologies to force museums to confront their colonialist policies when they refuse to repatriate objects. For example, the British Museum is the worst. Even outside the context of tribes, the Greek government hasn’t even been able to get the Elgin Marbles back from them over the course of decades so getting back a basket is a longshot. The Grand Ronde not only have their belongings in the British Museum and dispersed all over the world, but they also have their belongings in the holdings of local museums. I’m working with tribes to access collections, document objects, then generate 3d models and replicate them so that they can then be used as proxy objects, or stand-ins for the original object so that museums will have little excuse to return what rightfully belongs back to tribes.

What’s the ultimate goal with these efforts? Is there a limited scope or are you hoping this expands?

I think the ultimate goal is that I’d take a back seat to this work. I think this should already be part and parcel with the best practices of museums today. It seems obvious, but we’ve seen time and again that it’s too hard to relinquish that colonial power. I think my desire to take a back seat is also in relation to your other question about whether I’ve faced any pushback or resistance to the project. I haven’t. At least not from the university or the Grand Ronde. In terms of the tribe, before I began working on the project, I approached them and asked for their permission to work with their story and research its history, and then presented my ideas to them along the way. But even with their approval, I’ve had to deal with my own internal critic. As an artist of color, I’m pretty sensitive to cultural appropriation and so I’ve had to both ask and then trust that I’m not co-opting narratives for my own ends or in a way that’s not helpful within a larger context of social justice struggles or even just representation itself. I do want to continue to explore the idea of the copy or replica with future work too. I’m interested in the ways a copy might be imbued with value rather than framed in terms of loss or a lack of authenticity, and for that value to come outside the context of a formalist art aesthetic or history.