This autumn I was invited to exhibit two projects that I’ve made in the past decade as part of “Checks & Balances”, curated by Murray Horne at SPACE in downtown Pittsburgh. Both of these projects were created at different times, and both focus on Coyotes. I keep coming back to Coyote in my work for a myriad of reasons: biological, mythological, personal. In simple terms, Canis latrans has been evolving and expanding across this continent faster and with more success than any other large predatory mammal — despite our contemporary place at the top of the food chain, there’s basically nothing we can do to change this fact. This is a wholly different scenario than, say, the colonial history of wolves. I believe there’s much to that, and I’ve been poking at this history through several projects over the years.

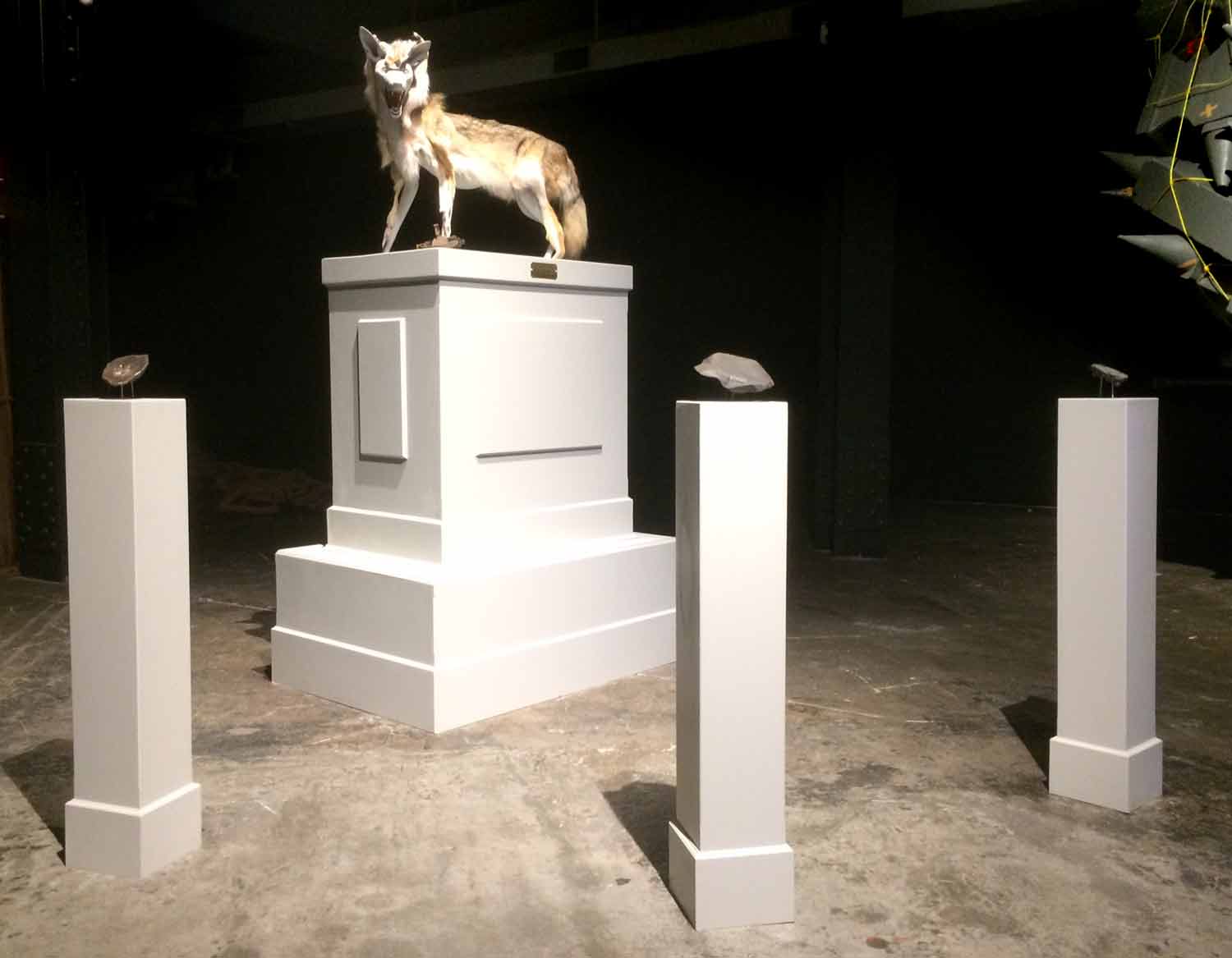

Shaun Slifer: Shapeshifter, Canis latrans, coyote pelt, leghold trap, taxidermy mannequin by John Schmidt (2012)

I wrote up this text about the work, although it never made it into the exhibit itself:

Imaginary, human versions of wildlife stand both in parallel and in contrast with actual animals through our cultural vehicles of media, myth, and anthropomorphism. The contemporary American understanding of our cohabitation with Coyote is a polyglot of various Indigenous stories, resonant settler-colonial misunderstandings of “prairie wolves”, and news media scare-stories buttressed by state-led bounty programs and federal eradication missions. Fundamentally we may often overlook the biological reality that coyotes will continue to adapt and spread regardless of our efforts at elimination, but a shift in this paradigm is unfolding.

Akin to the stoic memorial architecture of cemeteries and hero monuments, Shapeshifter is a statue in flux, a human-made effigy of Coyote incapable of maintaining a static relationship to the reality of evolutionary biology. Shapeshifter is a monument to an actual presence in continual, fluid transformation.

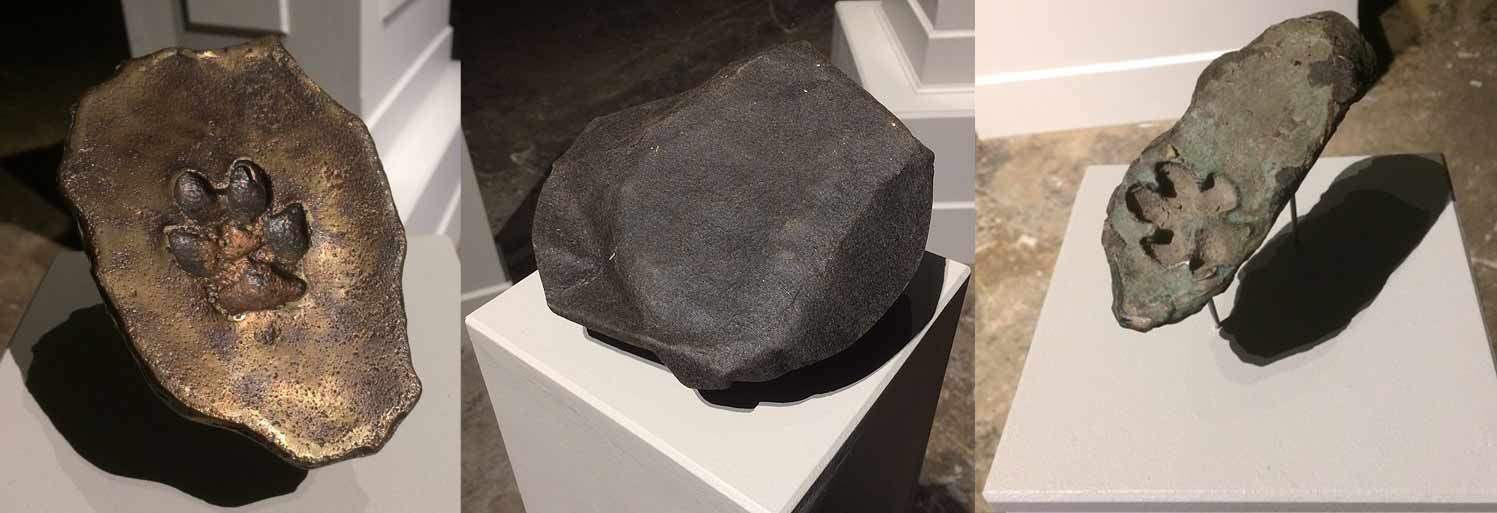

In 2007, I cast several dozen bronze coyote tracks in “puddles”, a series called Between Dog & Wolf. For several years I installed these in small potholes in asphalt city streets – primarily in Pittsburgh, but also in several other US cities as I traveled. On installation, the embedded bronze is initially hidden by tar paper, and becomes exposed after the covering is worn away by the continual grind of motorized traffic. Asphalt crack filler serves as the bonding agent, so that by the time the tracks become visible they have already become a part of the street. Exhibited are three samples from this project: a finished piece, a tarred piece ready to install, and a piece I unexpectedly managed to find, dislodged from it’s pothole, several years after it was installed.

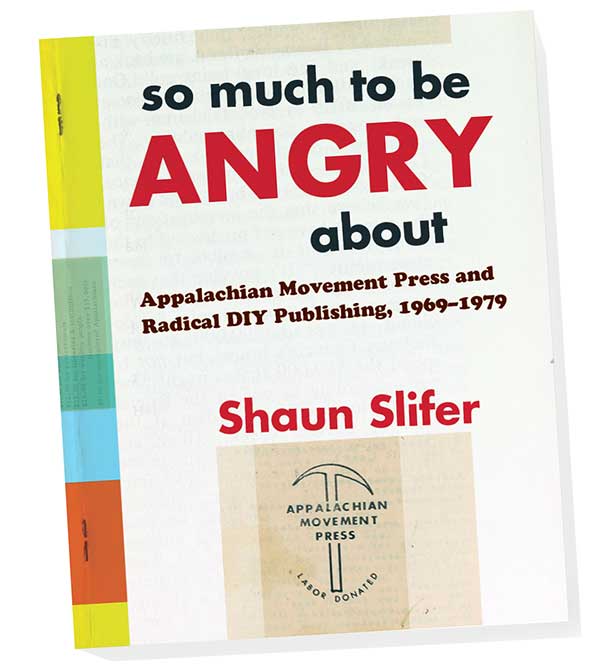

Recommended Reading:

Coyote America: A Natural and Supernatural History, Dan Flores, Basic Books, 2016

The Voice of the Coyote, J. Frank Dobie, Curtis Piblishing, 1947

Where the Wild Things Were, William Stolzenburg, Bloomsbury, 2008

Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, and Art, Lewis Hyde, North Point Press, 1998

More information about the exhibit can be found here.

Update 11.9.16: Lissa Brennan at the Pittsburgh City Paper wrote a nice review of the show!

Below are some shots I took of the other work in the exhibition, all by regionally-based sculptors.

Sarika Goulatia: The Trivial Pursuit of the Superfluous, found objects (including car hood, television and radio, household objects, individual white sculptures, mini Roman chapel, bird cages, wrapped figures) juxtaposed with pinned shirt collaboration with Rita Malik, Maanya Goulatia, and Eshaan Goulatia. (2016)

Paul Bowden: Two Figures, Front to Front, gypsum cement, spray primer (2008)

Jill Larson: Bittersweet, bed frame, 1, 715 nails and 1,715 Hershey’s Kisses (2016)

Jasen Berthisel: This is Revolting, mixed media (2016)

Brandon Boan: TER.RA.ROAM, Iron oxide clay, polished chrome wheel (2016)