April 11, 2017

Chip Thomas

Dr. Chip Thomas, also known by his artist name Jetsonorama, lives in Tuba City, Arizona, on Navajo land. For thirty years, he’s worked as a doctor in the Painted Desert region, treating patients with common health issues as well as older patients suffering from mining exposure during uranium extraction.

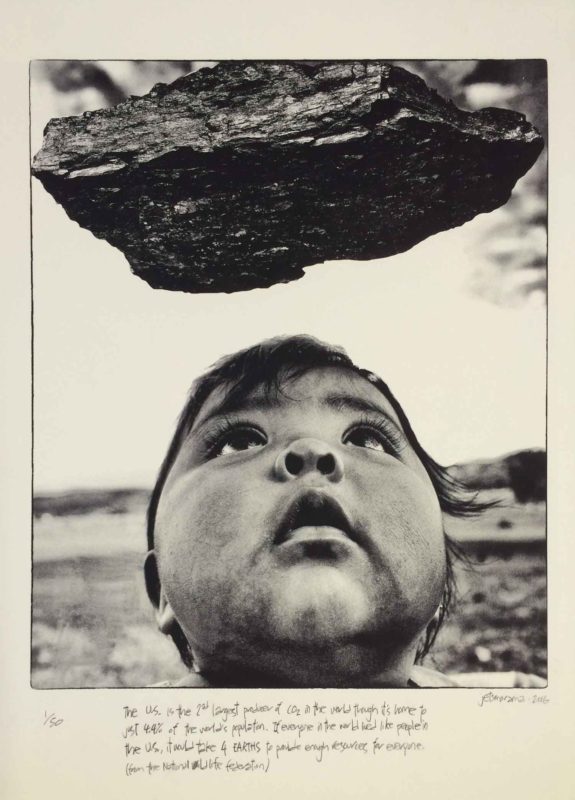

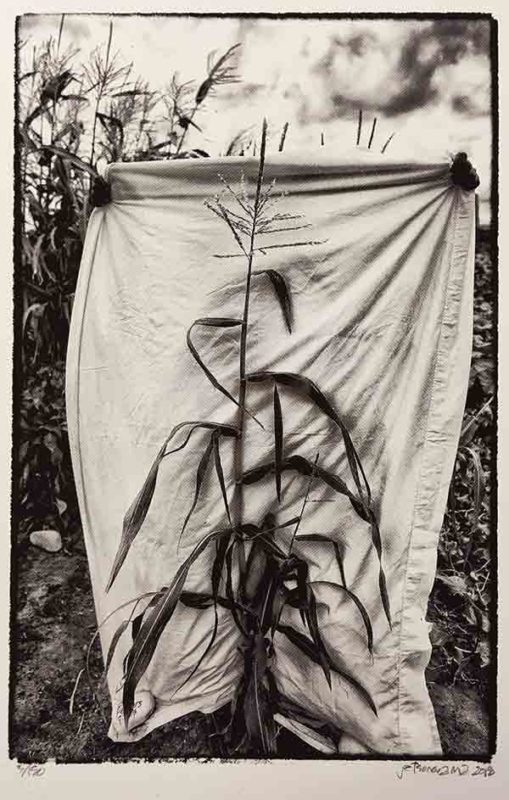

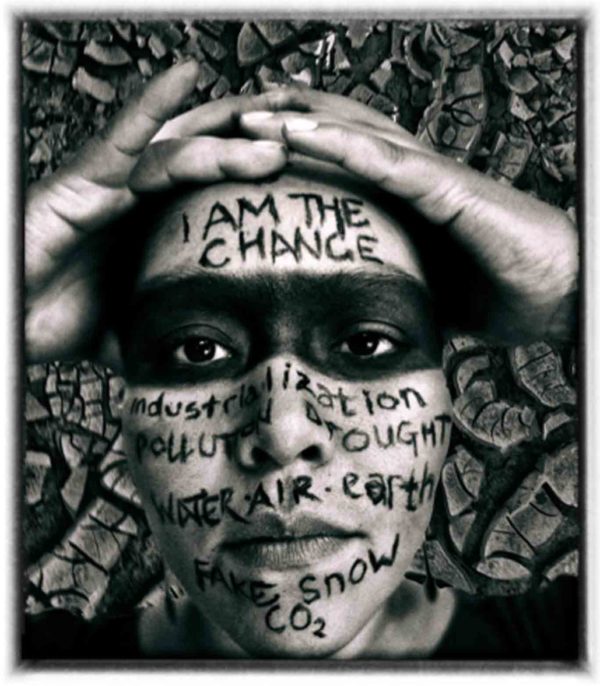

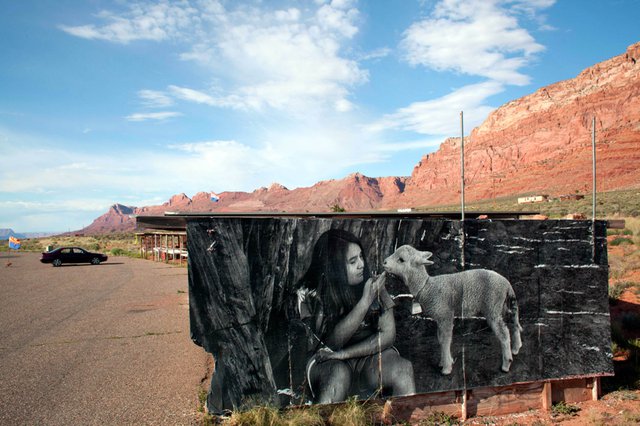

Seeking to bring awareness to the issues faced by people in this region, Thomas began using a lifelong photographic hobby to create “wheatpaste” posters—large photos of Navajo residents glued with a water-flour mixture to water tanks, grain silos, and roadside art stands. I spoke with him recently in Joshua Tree, California, where he was working on a new installation.

Q: What led you to take your photography of Navajo residents and wrap it around issues such as global warming and social justice?

Chip Thomas: I started photographing in black and white in a photo documentary style in 1987, when I first moved to the Navajo nation. From the beginning, I enjoyed spending time with people as they went about their day-to-day chores such as hauling wood, coal, and water, or just being with family. I attempted to tell stories of community members I photographed.

As a person of color raised in the South, my concern for social justice comes easy. I’ve always been interested in cultures from around the world. Social studies was my favorite subject in primary school. Photographing and storytelling in the context of the reservation was an organic evolution.

As a person of color raised in the South, my concern for social justice comes easy. Photographing and storytelling in the context of the reservation was an organic evolution.

Courtesy of Chip Thomas

Chip Thomas and one of his many installations on the Navajo reservation.

Q: Explain how your art connects with issues of health and the environment.

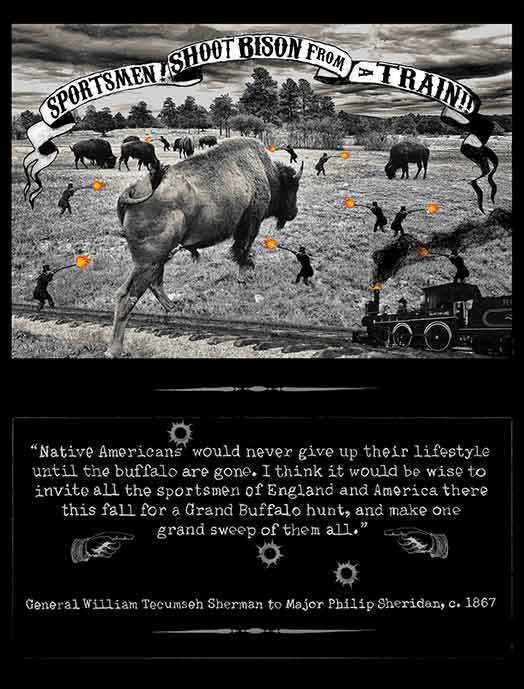

Thomas: As a physician, I see a lot of older men with chronic lung problems who use supplementary oxygen in order to perform activities of daily living. The majority worked in the uranium mines on the Navajo nation in the WWII and Cold War era and are suffering health consequences from the lack of protection and information afforded to them at that time. When companies started mining uranium here in the 1950s and studying the Navajo miners (without telling them of the health consequences of their work), it was thought initially that the Diné, or Navajo, had a gene that prevented them from getting cancer because the rates were so low. However, various cancer rates in the Diné exceed the national average.

In light of multinational mining companies wanting to mine the north and south rims of the Grand Canyon for uranium, which will be transported across the western part of the Navajo nation to mill sites in Utah, and the detrimental effect this has on the environment and human health, I most definitely plan to do more public art work around this issue.

The uranium issue is multifaceted in that there’s the concern regarding cleaning up the 523 abandoned mines that haven’t been sealed from the Cold War period which are contaminating the land, water, animals, and people to fighting new efforts at mining and milling in and around the reservation.

Chip Thomas

Q: You were the son of a doctor, am I correct? Do you think that made a difference in your racial outlook, versus say a factory worker in Detroit or a farmer in Mississippi?

Thomas: My desire to commit to an underserved community came from three years at an alternative Quaker junior high school in the mountains of North Carolina, where the emphasis was on building community. There’s a tradition within Quakerism of witnessing or holding presence, which involves going to areas of conflict, engaging with people affected such that what is learned and witnessed can be shared with a larger audience. I see my art project of pasting large black and white images of people from the community along the roadside as a form storytelling or witnessing.

There’s a tradition within Quakerism of witnessing or holding presence, which involves going to areas of conflict, engaging with people in order to share with a larger audience. I see my art project of pasting large black and white images of people from the community along the roadside as a form storytelling or witnessing.

Chip Thomas

Q: I grew up in a community with a largely Mexican population, and it was romanticized in my house as a culture full of good food, people that laugh a lot, hard workers—but my mother always locked her purse in the trunk. I often think the same about tribal cultures around the world. The photos out of Standing Rock come to mind—young people heavily vested in Burning Man wearing braids and feathers in support of a culture and people they learned about in movies. Do you see this . . . misguided romanticism?

Thomas: For the past thirty years, I’ve lived and worked in a small, isolated community on the Navajo nation. Though we’re close to the Grand Canyon, Lake Powell, Monument Valley, and Canyon de Chelly, which get lots of tourists, I don’t see a lot of tourists in my immediate community and don’t really have to engage the question of misguided romanticism.

Having said that, I give those who are getting out of their comfort zones and exploring new and different cultures credit for doing that. They’re not sitting at home watching Fox News believing alternative facts. Instead, they’re on the front lines raising money and awareness about resource exploitation while getting tear-gassed, concussion-bombed, and water cannon-blasted in below-freezing temperatures with our indigenous sister and brothers. I’ve got no issue with those folks standing up for what they believe in. Quite the opposite. Respect to them.

Q: How do you feel watching social media concentrate on #blacklivesmatter when you’re surrounded by people in poverty, smack dab in the middle of the most developed nation maybe in the world?

Thomas: Well, it’s about working for social justice where you are. The Diné nation is 27,500 square miles in size and is home to approximately 180,000 people. The land is rich with water in aquifers, coal, oil, natural gas, and uranium. With these resources, the Diné should be the materially wealthiest community living in the Western hemisphere. But because the reservation is treated as a colony, the contracts for exploiting these resources were written to benefit multinational corporations and not the Diné.

Instead, the unemployment rate here is over 50 percent. Twenty five percent of the people here don’t have running water or electricity, yet I live thirty miles from the Peabody Coal Mine and fifty-five miles from the Navajo Generating Station (a coal burning power plant), and Glen Canyon Dam (a hydroelectric dam). There are grassroots organizations across the reservation addressing these issues locally and at the state and national levels. But, sadly, change is slow.

If your question is why is it that I as an African-American man am not advocating for social justice in the Black Lives Matter movement, I’ll share with you something I shared with a friend twenty-two years ago. In a sense, I feel like a modern-day slave in that in my day-to-day life on the reservation I don’t have to deal with institutional racism or racially based abuse outside the work environment, as many of my brothers and sisters do in their interactions in urban areas. Just as escaped slaves found solace in indigenous communities back in the day, I have found that here where I feel that the work I do makes a difference.

Just as escaped slaves found solace in indigenous communities back in the day, I have found that here where I feel that the work I do makes a difference.

Q: Tell me about the Painted Desert Project.

Thomas: The Painted Desert Project grew out of a conversation with a fellow street artist in 2012. I see it as a case study in building community while sharing the tools of muralism with interested members of the community. I’ve taught a few youth on the reservation my process who have expressed interest and have conducted workshops at universities across the country. I’ve done some pieces with my fellow Justseeds member, Jess X. Snow.

Q: What does your artist name—Jetsonorama—stand for?

Thomas: My birth name is James Edward Thomas Jr. My initials are JET. As a kid in the 1960s, I used to love the Jetsons. In 2009, when I created my gmail account, I wanted jetson@gmail.com as my email address, but Mr. Google said that name was taken and suggested three other names. One of the three names was Jetsonorama. Loving mid-century modernism and being a child of the atomic age, I loved the “orama” reference and went with it.

Chip Thomas

Free downloadable copy available here. Courtesy Chip Thomas.