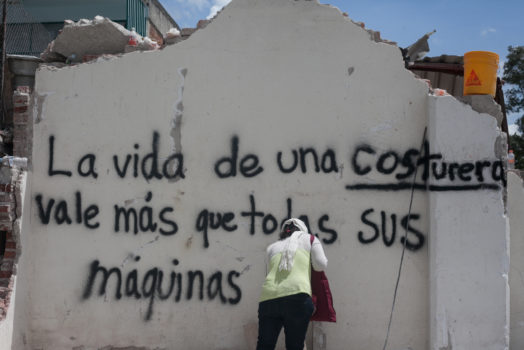

–Photo by Hazael R., www.flickr.com/photos/tuitstar

On September 19 of last year at 1:14 pm, a 7.1 magnitude earthquake hit central Mexico, affecting the states of Puebla, Morelos, Mexico State, and Mexico City. More than forty buildings collapsed and approximately 370 people were killed, most of whom were in the capital. Beyond the shock and tragedy of the earthquake in itself, the strangest, and even cruelest, twist had this earthquake fall exactly on the 32nd anniversary of the even more devastating Mexico City earthquake of 1985. Around 10,000 people died on that day and every year the city commemorates this great loss with an evacuation drill. On this past September 19, at 11 a.m., many in the city dutifully left their offices or homes to reflect on the tragedy of 32 years earlier only to have a real earthquake hit two hours later, without any warning.

Some of the legacies of the ’85 quake were the stories of solidarity, a lingering DIY spirit, an intense distrust of authority, and the concrete, anarchic, example of citizens self-organizing and taking the rescue efforts into their own hands in the face of an unresponsive government. The legendary “Topos” (“Moles” volunteer rescue teams) were born out of the chaos of ’85. The tragedy left an indelible scar and long-felt reverberations that include a traumatized generation across the metropolis. Politically it had an immense effect, revealing the ineptitude of the centralized and authoritarian regime of the long-reigning PRI, which was incapable of mobilizing rescue efforts and was to blame for the rampant corruption that allowed for pervasive shoddy building construction.

All of this background is important, I think, to understand the reactions to this latest earthquake. Many strict building codes were put into place after ’85, for example, yet a deep suspicion haunts the population that corruption is still putting our lives at risk. Likewise, deep tensions still exist between citizen’s groups and the army or other governmental bodies. During the aftermath of this last earthquake, rumors spread that the government preferred a quick clean-up to drawn-out rescue efforts, resulting in heavy machinery being brought in to remove collapsed structures before they were sure that all the victims had been removed.

The response to this past, 2017, earthquake has had many similar characteristics to 1985. Citizens brigades were quickly and efficiently created. A heart-bursting feeling of solidarity swept through the city and is still felt now, six months later. And the governmental bodies were again being criticized and scrutinized. This time, however, social media played a huge role in communication and organizing. Also, the relationship between citizens groups, the army, and other government agencies is a more complex one with a lot of gray areas.

I decided to do these interviews because I myself could not participate on the ground in the immediate aftermath of the terremoto on September 19 (S19) as I was doing fulltime childcare for my 1.5-year-old. However, I saw many of my friends and colleagues doing amazing work: organizing brigades for food and tools, often in bicycle brigades; collecting and sewing clothes for those left without homes or possessions; doing childcare and children’s entertainment in the emergency shelters; and on and on. I hope that these interviews help to keep alive the spirit of transformation that was so palpable in those final days of September. Many new connections have been formed, groups have come together, and a strong autonomous vision (although still a blurry and ill-defined one) has only just begun to be realized. –Sanya

These will be a series of interviews, published in both English and Spanish (will be published separately for questions of space). All translations done by me, not professionally, and with the best of intentions.

Collapsed building site at San Luis Potosí and Medellín Streets, Colonia Roma. Citizens moving debris. — taken from Wikipedia, photo credit: ProtoplasmaKid

Where were you when the earthquake struck? What did you do?

I was in Colonia Condesa, in my office, we did not do the previous earthquake drill because we were very “busy.” Around 1 pm the earthquake hit and we all went running to the street. Once outside we realized that it was not just any “temblor” [slight earthquake], and we began to see columns of dust in Condesa. I took my bike and ran to my sister’s house because she lives with her two girls. Then I went to my house and workshop to check that everything was fine and then I returned to the Condesa with tools and mask and to support what I could. The city was already in chaos. –Chucho

I was in ATEA [a maker and artist space in downtown]. I made sure that it was actually an earthquake because of my unfamiliarity with them while in the downtown area of the city. I kept calm and confirmed with my two colleagues, all this with visual language. I called out loud the need to leave, and I left calmly, but when I felt the violent movements I began to run. Within the next 45 minutes, I had joined citizen’s brigades. –Maiqo

I was downtown, in the Havana Cafe. I helped an older woman who was so frightened she could not walk. We waited a few seconds at the entrance and then left. –Yobany

In the immediate aftermath, did you realize the extent of the devastation? What was the role of digital media and social networks?

It was a matter of a couple of hours to realize that things were very bad. In social networks, information was shared about what was happening, and when riding your bike around the city it was easy to see the damage. I think the internet and social networks facilitated many things, however, there was also an abuse of the use of them and that could be counterproductive. As the hours passed, a lot of false news began to circulate from people who were not near the disaster areas. I think these networks were very useful, but it is difficult to control what people share in them. –Chucho

I became informed immediately [about the situation] because Wi-Fi was working and I had access to a mobile phone. I could see on Twitter the magnitude of the catastrophe. –Maiqo

Yes, I think that I knew that all around window panes were falling and dust was rising between buildings and homes. Within seconds some videos were circulating and some people could communicate with their loved ones I think. –Yobany

What did you do to try and help? What was the situation on the ground (at each site, or at a particular site)?

The first thing was to help in the immediacy, to bring tools, water and face masks to the affected areas nearby. Then the need arose to organize as a group to be able to support particular sites. We supported as we could in Chimalpopoca Avenue, in Laredo Street, in Álvaro Obregon Avenue and we even went to Taxqueña [zone in the southern part of the city]. We took part of the tools and equipment that we have in the workshop [at ATEA] so that it could serve carpenters and people who were rescuing. We installed a support station for cyclists — who were the fastest moving things in these situations. The strategy was to help where we were most useful. After extensive work in several places, I gave most support in Taxqueña because I noticed that there was a lack of knowledge in tools there and it was of vital importance to solve the needs of rescuers in the disaster areas. –Chucho

I responded [to the crisis] almost immediately from the first day and worked intensively for 15 days helping at different places and in different self-organized ways, many times with my colleagues at ATEA. –Maiqo

Citizens moving debris at the site of the collapsed garment factory on Chimalpopoca and Bolivar Streets, Colonia Obrera. — taken from Wikipedia, photo credit: ProtoplasmaKid

Citizens moving debris at the site of the collapsed garment factory on Chimalpopoca and Bolivar Streets, Colonia Obrera. — taken from Wikipedia, photo credit: ProtoplasmaKid

What are your biggest impressions from the 1985 earthquake? How did the society change after the ‘85 earthquake, if at all? What did the population learn then that was applicable to this earthquake?

I do not have much knowledge of what happened in ’85, only what people talk about and say. There is the annual drill that takes place in Mexico City [on that date] and from that time a rescue brigade called Los Topos emerged. I think that was what remained of that time. Maybe the people who experienced the ‘85 earthquake could be more clear about this. –Chucho

I did not live through the 1985 earthquake, except as an infant. I was 2 years old. I think there is a notion and social conscience (almost natural) among the inhabitants to self-organize and act proactively. I do not know if there are reminiscences of what was learned, socially speaking. –Maiqo

In my mind there are three [outstanding] images: one, the floor where I was standing raised up; another, the damage to the schools in our neighborhood; third, the maddening lack of water for weeks in the borough. Images of fallen buildings… –Yobany

Did Mexican society change after the ’85 earthquake? Did the population acquire any knowledge that it could apply to the response to this most recent earthquake on September 19th?

Yes, it changed. It got organized and had more solidarity. It knew that it was strong and self-reliant. I think [we did learn] a bit. We were another generation, but at that time we turned away from the government and self-organized anarchically, without authorities. The government did not have nor has the slightest idea how to resolve what happened. –Yobany

Part of what filled my heart and soul is the way in which people were organizing — what seemed to be horizontal structures, aided by social media networks. Did you experience horizontal forms of organizing? What forms of organizing did you see? What role did autonomous networks play in the kinds of aid that were set up?

It was exactly like that, horizontal and completely autonomous. People came out to help without having a role or a specific task, and little by little they were creating structures that allowed them to work better. Also, little by little I realized that in each place, in each place of collapse, there were people who I knew personally. There was a day in which I went through many of the collapsed sites on my bicycle and I noticed that in each place I knew at least someone who was helping, people who you usually meet at parties, events, or just people with whom you have collaborated. That also generated a prevailing environment of trust and support, even when the information on social networks was beginning to be doubtful, I was happy to know that I knew someone else [there] and that I could send any type of tool or help from the site that I was supporting. It was like seeing the same people that we always see doing something around the city. –Chucho

I saw them, yes, but they were very brief luminous points in different points and situations. I also saw a lot of desire to help in a lot of people, but almost no one knew how to do it. –Maiqo

Yes, of course, I saw it and I lived it, too. People removing the rubble, bringing goods all day and all night to serve others without expecting anything in return, taking over the streets and the affected sites and turning into a kind of people’s army, of the people and for the people. –Yobany

What do you think of the tensions between popular organizing and the army and other formal governmental bodies?

I think it was a time when nobody knew what to do and nobody knew how to act, the same army that is supposed to be prepared to help in this type of disaster did not know what to do. Many of these tensions were due to lack of knowledge. In my experience helping in Taxqueña, things were very coordinated and people were working hand in hand with the army. The army supported the citizens, even defending them from some government groups that wanted to take advantage of the situation. After all, the soldiers were only receiving orders, and if their leaders were bullied sufficiently by the citizen’s brigades, the citizens could demand that they help in more useful ways. For them, it must have also been frustrating to be sent to help and not know what to do. Many people did not know what to do. I think that in many cases any conflicts were due to outside antagonists, lies in the media, or even groups that generate confusion. I did not feel it was too tense, at least where I was helping most of the time. –Chucho

I experienced this firsthand in the Multifamily Tlalpan, [where I helped to] maintain calm between civilians and military and police forces. The government has a very low acceptance level among the civil and popular masses. Almost any action that [the government does] is rejected, if it’s purpose is not immediately apparent, such as the demolition of buildings and almost immediate intervention of heavy machinery without any explanation instead of allowing for the possibility of rescuing survivors in many points of the city. –Maiqo

What I think is that we have different and conflicting interests. They want to cover up and erase their illegal actions and corruption. We [want to] help, join together, and solve [the problems]. –Yobany

Where do we go from here?

To build tools that allow us to be prepared, to generate awareness and learn to work together. To share knowledge and generate new ways to teach those who are younger. To accept that this idea of an earthquake is present every day. To not forget, to continue helping those that need it, to collaborate as much as possible with those people who remain affected by the earthquake and its aftermath. –Chucho

I hope that we become a just and self-governed society. –Maiqo

To create another earthquake in political and economic realms, its epicenter being our organizations. –Yobany

Volunteers moving debris in a collapsed warehouse in Chimalpopoca street, Colonia Obrera. — taken from Wikipedia, photo credit: ProtoplasmaKid