While working on my posts about the covers of books about prisons (JBbTC 39–45, 52), I started a folder of Angela Davis covers, which has now grown large enough to be the basis of its own series of posts. About a third of these covers are books I have, another third are from friends (thanks again Ret!), and the final third from trolling the internet. Although an academic and an intellectual, it was Davis’s connections to action that first brought her into the spotlight. In 1970-72 she was arrested (after a national manhunt by the FBI), tried, and eventually acquitted for kidnapping and manslaughter for her alleged role in Jonathon Jackson’s failed attempt to liberate the Soledad Brothers.

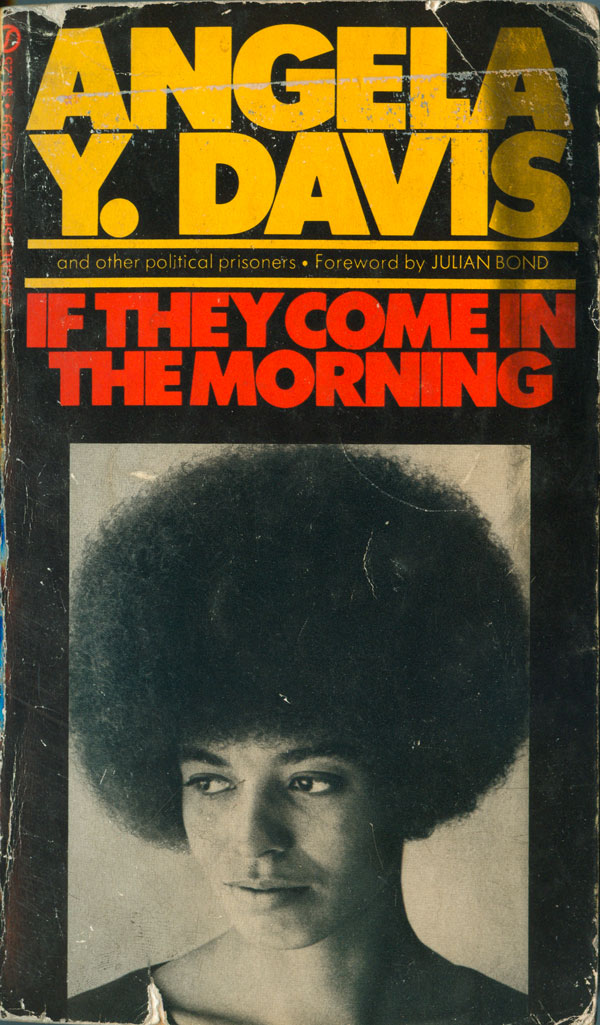

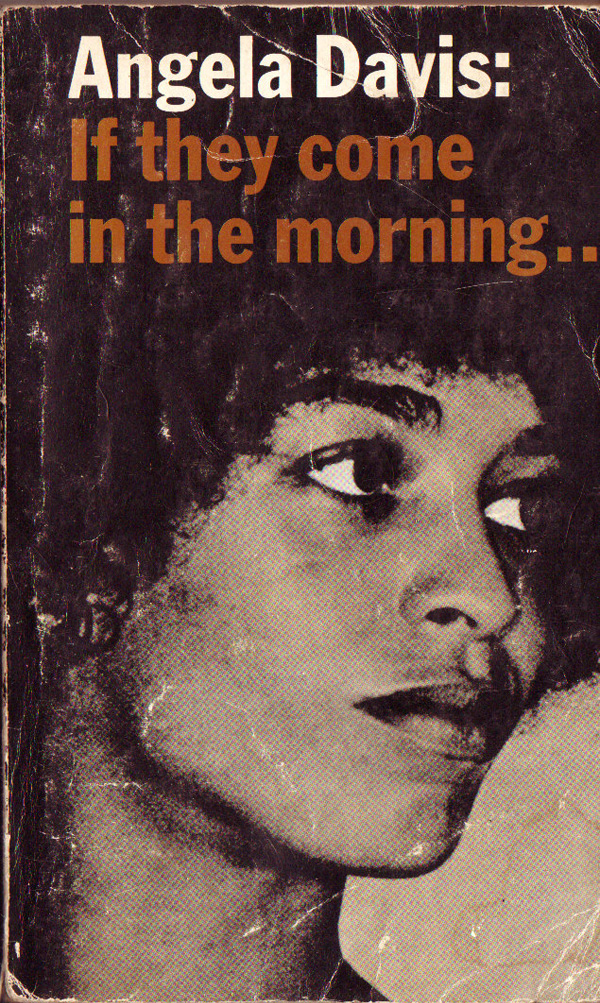

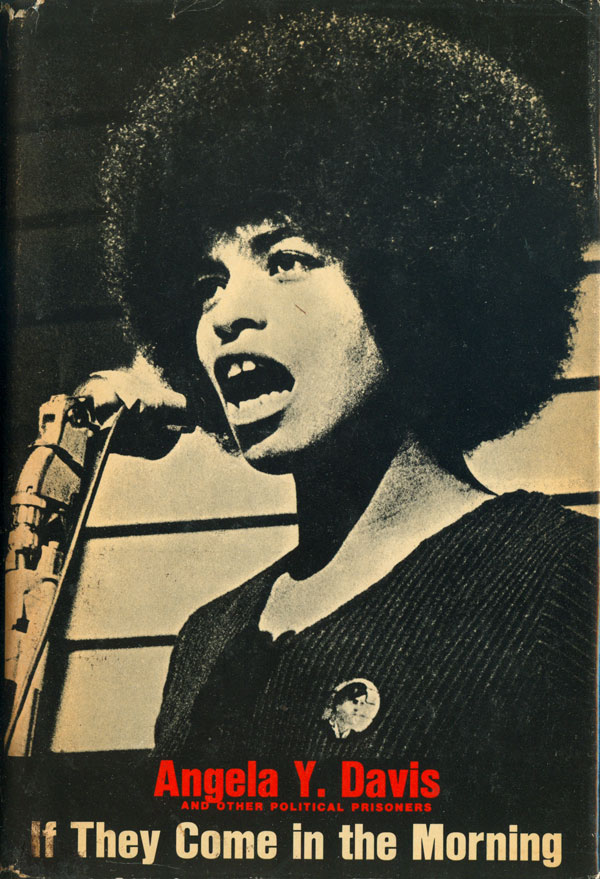

This led to the publication of her first book, an collection of essays about political prisoners edited while in jail awaiting trial, If They Come In the Morning. The first hardback edition (left) was produced by her support committee (and a later edition by Third Press), and originally intended as a tool to popularize Davis’s struggle. It was quickly produced as a mass market paperback in 1971 by Signet/New American Library, I would assume her support committee saw this was an attempt to mainstream and popularize the struggle of political prisoners and Signet saw an opportunity to capitalize on the world’s most famous afro. At the same time the paperback version was also published in the UK by Orbach & Chambers Ltd., with a different cover.

All three covers depend on Davis’ recognizable face and afro for their effect, on the hardback the title and name are almost pushed off the bottom of the page by the dominant image of Davis mid-speech. The Signet edition uses the most subdued image of Davis, she’s not speaking or marching, just quietly looking off to the left. The UK paperback uses a different photo, one that might be familiar to people as the image converted into a Free Angela poster by Cuban designer Alberto Beltran, than that designed image was again re-used wholesale by Shepard Fairey (see HERE). I can understand the desire to use this image, she looks strong yet human, purposeful yet approachable.

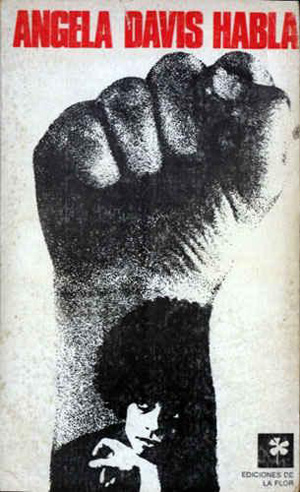

After her fame related to the court case, a book called Angela Speaks was released (possibly without her permission or knowledge?) and it appears only in non-English editions. I found Spanish and French editions, both below. The French edition, published by Nostre Temps in 1971, uses the same photograph discussed above in a simple, efficient design, and the Spanish edition, published in 1972 by the Argentine press Ediciones de La Flor, uses a different photo, montaged into a fist, but the afro is still front and center.

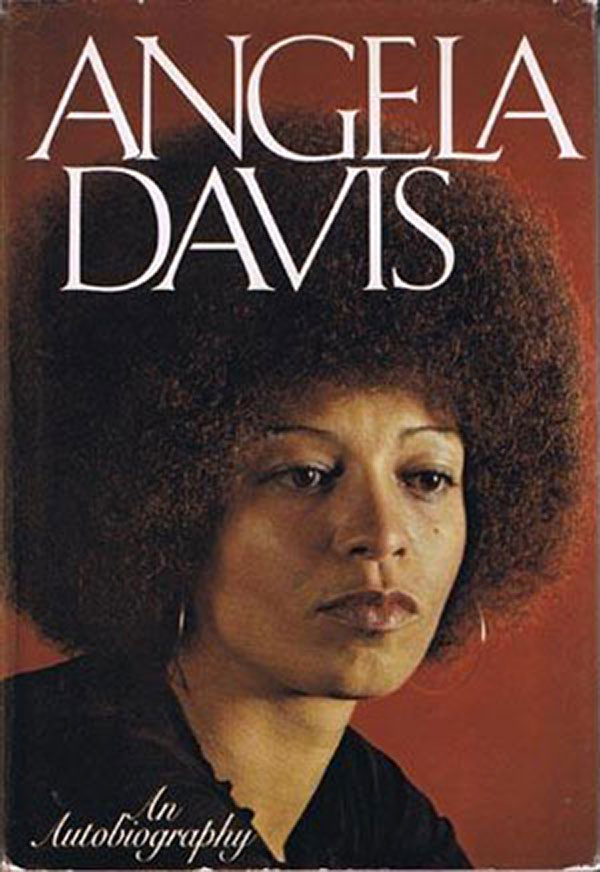

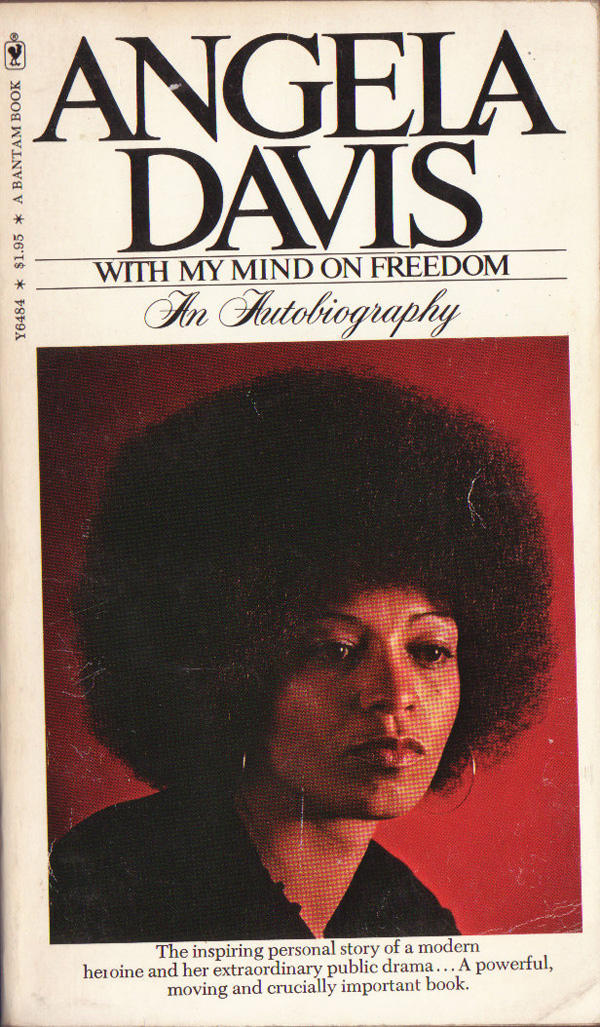

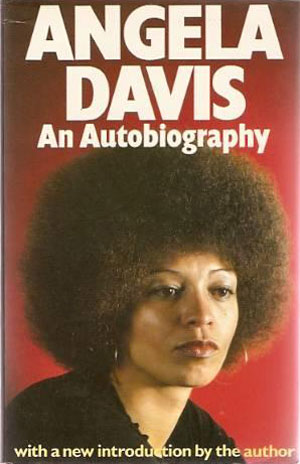

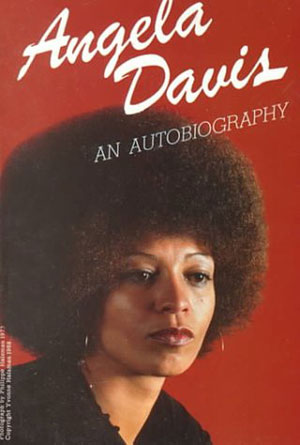

In 1974 Random House released Davis’ Autobiography. Once again, her face, and hair, are front and center on the cover, and on all the book’s covers to follow. The first edition, below left, has a certain style to it, the type is “classical” yet unique, and the image of Davis functions as much as a statue as it does a photographic portrait. In the 1975 Bantom pocket paperback edition this same image is confined within Bantom’s house style of the time, and a subtitle is added: “With My Mind on Freedom.” Although I’m not a huge fan of “photo floating in a box on a white plane,” I have to admit that it does give the eyes a rest from the super intense red of the photograph. Later editions of the book, both in the UK (The Women’s Press) and then the US reprint (International Publishers) use the exact same photograph, but try to update it with different type treatment. The Women’s Press’ block sans serif is a little more modern, but the letters feel like solid objects, and the way they hang at the top of the page makes the block of text seem like it is literally sitting on top of Davis’s head. The 80s reprint adds nothing to the original, and the author font is terrible. (I have also seen a couple other international editions of this book, but they all use this same basic cover, so it didn’t seem worth tracking them down.)

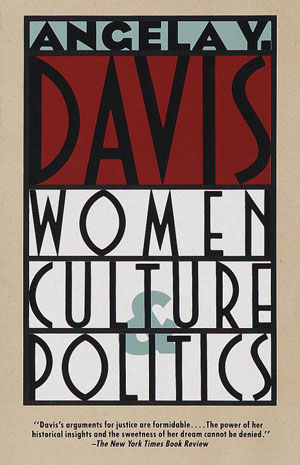

After her explosion of activist fame, Davis seems to have largely settled down to more traditional academic work, developing ideas and writing connecting her engagement with the world to her training in philosophy. Her next two books, Women, Race, & Class (1981) and Women, Culture & Politics (1989), have covers that support this idea. Both books are remarkable for how un-sensational they look. Part of this may be due to the 80s being the dark days of book design, but I suspect it is also a conscious turn away from celebrity and an attempt to re-brand Davis as a serious scholar whose work should be assigned and read in all of the newly minted Women’s Studies and Black Studies courses in colleges across the country. Certainly no one is ever going to accuse publishers of being overly concerned about the appearance of books they intend to be used as course texts.

The one thing that does carry over from the cover of Autobiography onto the dust jacket of the 1981 Random House first edition of Women, Race, & Class (designed by Robert Silverman) is the use of color, with the author and title embossed on a giant field of deep red. But unlike the Autobiography, which used a unique serifed type treatment, the font here seems to echo a romance novel more than anything else. For the 1983 Vintage paperback, the type appears chiseled out of wood and inked, like an inverted block print. Neither cover is particularly high concept, and there has been no attempt by the designers to engage with women, race, class, or Davis.

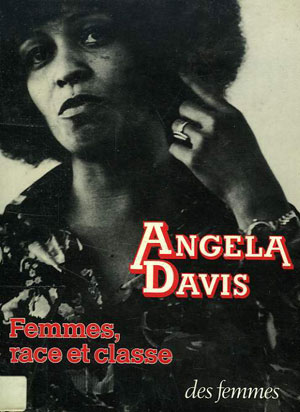

The cover of the original French edition published by Des Femmes in 1983 carries some of the spark of the earlier Davis books, carrying a photo in which she looks directly at the viewer, not in an aggressive way, but one that carries significant presence. The later edition’s cover is terrible, not worth thinking much about.

For the cover of her next book, Women, Culture & Politics, their is a similar avoidance of content. The Random House first edition uses an early 80s photo of Davis (dreadlocks have replaced the afro), but the type is the same as Women, Race, & Class and still uninspired. The paperback fairs much better, with the type creatively worked into a series of horizontal boxes, which to my eyes references German modernism (interesting since Davis studied in Germany, and was deeply influenced by the Frankfort School), although that may be unintentional on the part of the designer. This cover, designed by Jo Bonney, is an early, successful example of what is generally considered “post-modern” book design, with designers drawing from an array of graphic histories, and reworking these influences into new, contemporary looking work. But once again, there is little attempt to visually engage with the concepts of women, culture, or politics, which makes me think that this was a conscious decision.

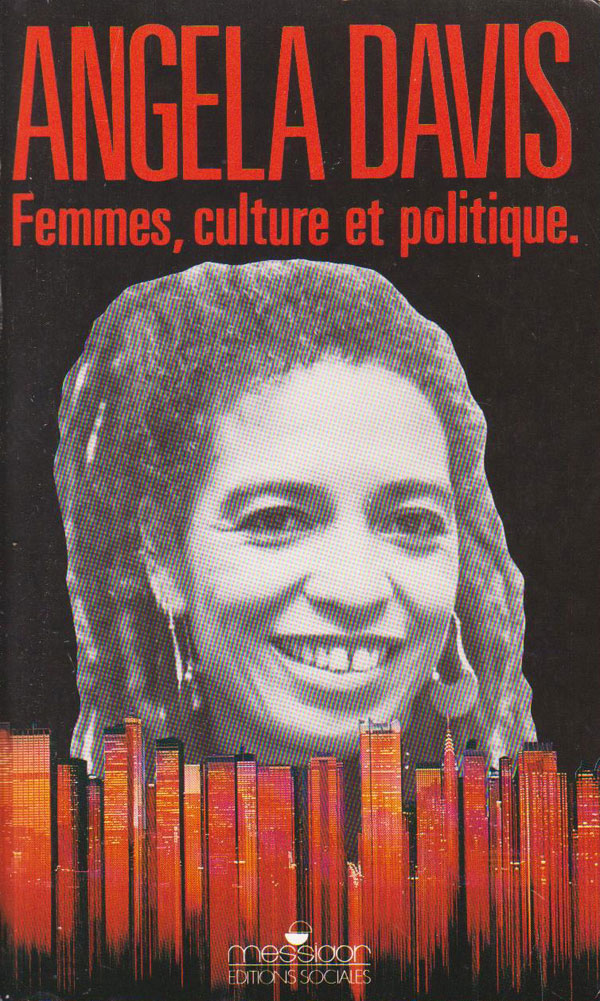

The French edition by Messidor (1989) is interesting but pretty strange, with Davis’s black and white head inscrutably floating above a red colorized cityscape.

Davis was fairly quiet in the publishing world for the next decade, with 1998 seeing the release of The Angela Y. Davis Reader (Joy James, ed.) by Wiley-Blackwell. The cover is one of those strange pieces of design that function somewhat effectively, yet still feel like they were an afterthought. The red of the past has been replaced by a copper-brown, and Davis is photographed in such a way that it is clearly a new photo, yet she is posed to evoke the famous images of her in the past. The titling is clean and strong, I like the sparseness. But I don’t understand why she is floating on a field of grey dirt, or is it rock? salt? the beach?

The most recent major work that Davis has published is Blues Legacies and Black Feminism (1999), which has a decent but unremarkable cover.

Next week I’m going to look at the infinitely more exciting output of pamphlets produced by or about Davis.

Davis is such an inspiration. I like the transition of the different covers of the books about her. I’m learning a lot from your post. Thanks for this!