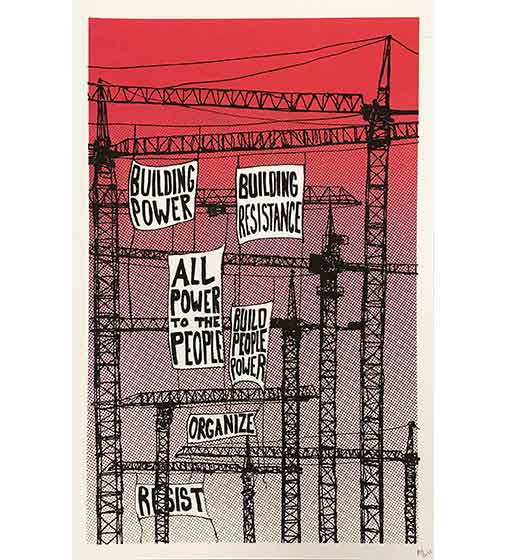

I met Daniel Drennan ElAwar from the Jamaa Al-Yad Artists’ Collective almost a year ago when we collaborated with Ethan Heitner, Stefan Christoff, and Kevin Caplicki on the Up Against the Wall exhibition at Booklyn. The exhibition highlighted the work of overlapping struggles working from opposite ends of an international movement for peace and justice and centered around the production of Boycott! kites designed by Jamaa Al-Yad. The walls of the exhibition were covered with prints from Imaging Apartheid and the Celebrate People’s History: Iraq Veterans Against the War portfolio. During the opening Daniel and Kevin printed mock-up kites for people to assemble and take home.

The exhibition and collaboration was energizing and connected artists, activists, and community members across movements. Inspired by this success, Daniel, Kevin and I set out to produce flight-ready kites based on the same Boycott! design for activists to use in actions across the country. We are excited to be releasing the kites through a series of kite flying actions with Jewish Voices for Peace this fall. The kites will also be available for sale on the Justseeds website this fall. You can download the Boycott! graphic from the Jamaa Al-Yad site.

In preparation for the release of the kites I wanted to reach back out to Daniel to get to know him a bit better and get his perspective on the exhibition, collaborating, and the Jamaa Al-Yad Artists’ Collective. Since my first interaction with Daniel I have been continually inspired by his process of engagement, grounding in theory, and his generosity. I found his responses in this interview much the same and I hope you get as much out of it as I have.

Aaron Hughes (AH): It would be great to get to know you a bit more. Can you share a bit of your background and how you got involved with Jamaa Al-Yad?

Daniel Drennan ElAwar (DDEA): In 2004 I returned to Lebanon, where I was born and adopted from. I was teaching graphic design and illustration, and my research focus was on artists’ collectives and their reasons for existing but also ceasing to exist. Like elsewhere in the world, activist art on the academic level was limited to “awareness campaigns”, usually as advertisements for humanitarian imperialist NGOs, as well as foreign monies directed at neo-liberal projects in the civil sector. I was at the same time extremely bothered by the “theoretical only” frameworks recommended to students to work within, which basically stated that change was impossible, and which we know now were supported by the US government and others as a way to subvert and co-opt resistance.

I had studied and collected references to the liberation movements of the 60s and 70s, and found this historical reference wholly absent from the academic realm, despite it still being quite active, locally speaking. And so my aim was to “put my money where my mouth was,” as it were, and see if it were possible to establish a truly activist organization based in resistance praxis, with absolutely no “taint” from the neo-liberal and capitalist systems we were forced to work within. It took almost two years to write from scratch our bylaws and charter, and in 2009 we received approval from the Lebanese government to exist as a non-governmental organization.

AH: This process and time spent developing Jamaa Al-Yad seems to have grounded it in a way that many art collectives are not. Can you describe a bit of how Jamaa Al-Yad works and is structured?

DDEA: Not to get too esoteric, but we are an organization without organization; meaning we work openly with communities and groups and we morph and change as we take on projects and work. We hark back to the days of communal and collaborative cultural production, whether via community printers, political agitprop produced in basements, or everyday creators of cultural resistance. We believe art and culture to be inherent to sound body and mind, and we attempt to express the idea that “existence is resistance.” We believe that cultural production is inherently tied to one’s most-local space, and we attempt to channel that no matter what we produce.

AH: I was really interested in the Jamaa Al-Yad manifesto as an in-depth visionary guiding statement. The manifesto opens with this quote by Paulo Freire, “One can abet one’s own destruction, or one can create.” For you, how does this simple quote frame out Jamaa Al-Yad’s in-depth theoretical manifesto?

DDEA: This quote resonates with me on a variety of levels, and I imagine for everyone in the group it probably takes on a different tenor. Primarily, it’s an acknowledgment that we live and work within particular economic and political systems that move and shape and destroy whether we are aiding and abetting them or not. And so the choice to be politically “neutral” to me is never an option, because that automatically sustains the status quo, which is a destructive force in and of itself. On a more spiritual level for me, it reflects an idea that every act, every decision, every thought carries with it potential for creation or destruction; everything we do leans in a particular direction, and it is within our will to shape things moving forward. The creative process, being creative, and being “non-destructive” in this light are all ideals to strive for, and all reflective of the same source.

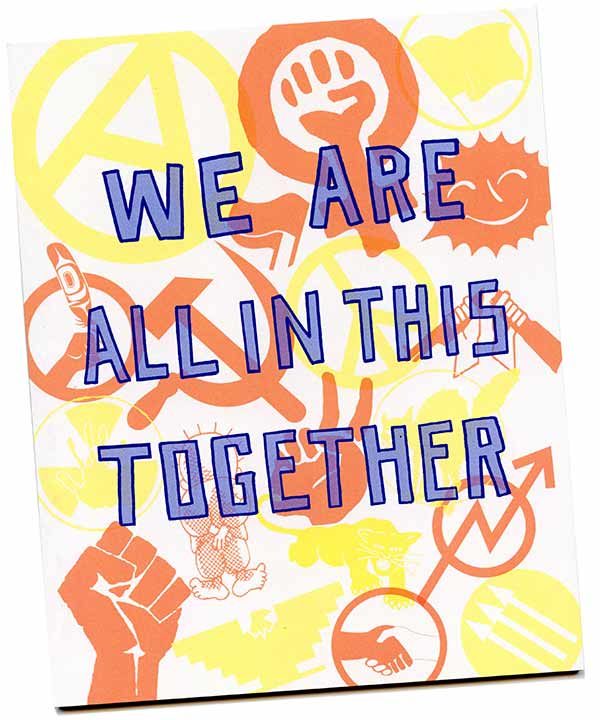

AH: This idea that in “… every act, every decision, every thought carries with it potential for creation or destruction …” opens up space for collaboration across great difference and perhaps opens opportunities for an intersectional political art practice. How has this framework opened up opportunities for unexpected collaborations?

DDEA: This is perhaps the exact foundational premise of Jamaa Al-Yad, so yes, exactly that question: “How do you find common cause across imposed boundaries and categories?” To sidetrack a bit first, I profess to not using the term intersectional, because it comes from an academic space that doesn’t manage to undo the categorizations imposed by a dominant culture; it accepts those and works with them. I find this hugely problematic, along with the fact that class is often neglected as a factor, especially within North American discourses. When I was living in Beirut, with its absolute sectarian strictures and inability to escape such categories, there is little of the luxury and privilege of intersectionality to help get through the day-to-day of such a toxic environment.

Having said that, I turn to historical precedence in this regard, perhaps because I am old enough to remember the anti-imperialist liberation movements of the 70s and beyond. The Black Panthers, OSPAAAL, The Lotus Magazine, etc. all proposed a kind of cross-pollination that was possible within a framework of mutual aid and support of various anti-colonial movements. There was a concept of difference but in the sense of it being functional to colonial and imperial mindsets. This is radically different from, say, the colonized putting forth those identity markers within the economic and political system that created them. This approach to me is invalid and doomed to failure from the get-go.

But the search for “common cause” is possible, though it requires a “stepping down” from one’s class position, I think, to attain. Some examples might help. When Juan Fuentes visited Jamaa Al-Yad in Beirut, we did a workshop in the Bourj Al-Barajneh Camp. Things were tense, because we were seen as yet another NGO coming through for their media photo op and street cred. I asked Juan to speak about his work, and he related his story as a Mexican American growing up in labor camps; his grandparents who were Mexicans before the American War of Aggression against Mexico turned them into Texans; the border wall proposed between the two countries, etc. As these terms were translated into Arabic, it was obvious that they resonated with the Palestinian youth present, and the energy in the room shifted positively after that.

Another example was the project, including lectures and a play, that we did for the anniversary of Malcolm X’s visit to the Southwest Asian region 50 years ago. I wasn’t sure what the turnout would be, but Malcolm X still resonates in that part of the world, and the lecture and play drew about 100 people. More personally, my own story of return to Lebanon found me eschewing the ex-pat lifestyle for life in a down-and-out Beirut neighborhood. Those who just “got” my story of adoption and return were similarly displaced, dispossessed, and/or disinherited. In turn I defined my “public space” based on where they were allowed to go, and this cost me much in terms of colleagues/friends and livelihood, but it provided much more in terms of legitimacy and brotherhood. Again, “intersectionality” would have me and my neighbors in a similar category; but class remained a chasm that needed to be crossed by me for anything productive to come of that connection.

AH: Does this relate to the collaboration for the Up Against the Wall exhibition at Booklyn? It is not often that arts organizations, organizations working for palestinian liberation, and US veterans’ organizations work together, yet for the Up Against the Wall exhibition you worked with members of Iraq Veterans Against the War, Imaging Apartheid project, Adalah-NY, and the Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative. Was this collaboration unexpected? What did it mean to Jamaa Al-Yad to be working with all these groups?

DDEA: It’s a really intriguing question, because for very intense and emotional personal reasons I think about this as perhaps the hardest line to cross. I remained in Beirut during the July War of 2006 and even though it wasn’t American soldiers on the “other side”, it was weaponry provided by American tax dollars, including expired cluster munitions from the Vietnam War that were dropped throughout the South. To be “anti-imperialist” means rejecting the means for this imperialism, which is the military, and so I do admit that my first response when presented with someone who has been or is currently in the military is a defensive posture.

Having said that, I have two brothers who both served in the Navy, and I can honestly say some of the more intriguing and useful dialogues I’ve had on the subject have been with them, especially considering my return to Lebanon. But my thoughts on this go back to when I was 10 years old, because I also remember my father taking me to the unofficial parade for returning Vietnam War veterans in New York City, and I remember a group of veteran protesters going by the reviewing stand and the entire body of those in the bleachers standing to attention and then about-facing, turning their backs on fellow veterans. I found this traumatizing on so many levels, especially today given the extremes of reception to veterans, with a rabid superficial patriotic support on the one hand, and complete and total physical and psychological neglect on the other.

But this is where it gets interesting, in that if we examine it from a purely class perspective historically speaking, the incentives to enter the military are often more economical than political, and the “revolutionary potential” is always latent, and it has been since Shays’ Rebellion. And so I separate the institution from the individual, and I would say as individuals both attempting to make a go of it within hegemonic discourses and the economic and political realities of our given capitalist and neo-liberal systems, there is no room for someone to stand up and point the finger at someone else.

It’s interesting too, because I remember mentioning to my brother the Combat Paper Project of the Printmaking Center of New Jersey as something I was interested in working on, but I was worried how veterans might see me: Arab, Muslim, etc.; I didn’t want to contribute to someone’s trauma in a space of attempted healing. He disagreed and said he thought the opposite; the fact that I shared similar experiences of war would give me the ability to better “listen” and “hear” than it would him, although he was a fellow veteran. My experience, in terms of discussions I’ve had with Vietnam veterans especially, has proven this to be true.

That said, going back to the idea of intersectionality, I think it is problematic because it posits commonalities where none actually exist. For example, graphic designers working in the Arab world you might think would appreciate the work of Jamaa Al-Yad. In fact, it is quite the opposite. We work in Arabic not out of some cultural nostalgia, for one example, but because that is the language of the majority of people we wish to reach. But these are the people designing manuals for occupying armies, and re-branding Israel after the 2006 war. So I think we have to get past these false divides.

AH: How does this kind of collaborative work reflect back to the political and theoretical beliefs of Jamaa Al-Yad?

DDEA: Again, if you were to ask everyone in the collective this question you might end up with quite different answers; our bylaws explicitly state, for example, that we all may come from different political or sectarian realms (that is the reality in Lebanon, sadly), but we have a core commitment to certain beliefs that allow us to work together. One of the ways of avoiding what is often a sectarian gridlock is to focus economically and politically on the historical movements of liberation in the Lebanese nation-state and region as well as the economic system and the class discrimination it imposes. So, for example, when we did our newspaper supplement for Israeli Apartheid Week in 2010, we focused entirely on the economical basis of apartheid. We refuse to engage in the mushy and Orwellian discourse of “human rights” or “poster children” of misery. We focus on a wholly agentive tradition of active resistance, because that is what we know, and that is what binds us together.

One of the interesting aspects of printing this newspaper supplement in particular was that the newspaper on the day it appeared sold out in many parts of the country and in Beirut especially. Many of the collective members working on it told me that it caused their parents for the first time to open up about their experiences of doing similar work during the war, especially in light of our recipe for wheat paste. So it activated multiple generations. But the true test was that it was republished in a variety of publications reflecting more or less divides in the political-sectarian spectrum. We saw this again during our project for the March of Return to Palestine, which managed to unite across the Lebanese sectarian divide but also along the Lebanese-Palestinian one as well. So it is possible; it requires a ten-fold of energy expenditure to accomplish however.

AH: How did that process play out for your contribution to the Up Against the Wall exhibition?

DDEA: We felt it was important to again stress the economic aspects of imperialism, colonialism, apartheid, settlements, etc. The emphatic nature of Boycott! is a rallying cry as well as an invitation to take part in a collective action. The symbolism of the kufiyyeh or Palestinian scarf has many layers and meanings, but here is a reminder that there is a lot of power in this quite simple piece of cloth with its uniquely Palestinian pattern.

AH: During the exhibition opening, your design with the kufiyyeh pattern and the word Boycott! in Arabic and English was screenprinted on paper kites. What was the meaning behind the use of kites?

DDEA: Our research showed us the various events that took place in Occupied Palestine that involved kite flying, often with children decorating kites and then setting them airborne, often in an attempt to break records. I also thought it was fascinating that Kevin’s research into kite production turned up a business out in Queens that makes kites, usually for Pakistani cultural occasions. The history of the kite worldwide thus has so many facets that are unique to local cultures, but it also speaks “universally” as a symbol of freedom and transgressing closed borders.

AH: It seems like for this collaboration the kite becomes not just a “universal” symbol of freedom but also a metaphor for intersectionality between diverse movements. How do you see the Boycott! kite reflecting that metaphor and representing the intersection reflected in the collaboration for the Up Against the Wall exhibition?

DDEA: Again I would caution against the use of particular terms, or the assumption of divisions. To assume a division is to create one. I understand that in current discourse it is important to acknowledge the various struggles that make up a greater cause of liberation. But this also has the potential to shut down alliances instead of creating them. So falling back a bit on the cultures that formed the basis of my day-to-day in Lebanon, I would say that the kite is a metaphor for a particular mindset that sees “us” before “me”; “we” before “I”. This is a crucial difference. To allow the individualism of the liberal and neo-liberal paradigms to impose too much on our worldview will be our downfall before we even finish standing up on two feet.

AH: Are there any other ways that kites have specific significance for this project?

DDEA: What is particularly interesting about the kite is that unlike other graphic representations of resistance―graffiti on the apartheid wall, for example―this one is seen on both sides; the kite cannot be avoided like murals, posters, and other cultural manifestations. Also, before the passing of the Oslo Accords, it was not legal to fly the Palestinian flag. So decorating a kite in this manner was a very powerful statement.

AH: What are your hopes for the future of this graphic?

DDEA: Like all of our graphics, we put it up and out there, and the use is left to the imagination of the downloader. Our work has shown up on T-shirts, on billboards, on television station breaks….I’ll leave this question to those who download it and use it. If one Palestinian child anywhere in the world puts this graphic up on her wall and is inspired by it, this will be more than I could have hoped for.

You can download Boycott! graphic here.

Daniel Drennan ElAwar was adopted via Lebanon to the United States at the age of two months. In 2004 he returned sight unseen, and taught graphic design and illustration at various Beirut universities for 12 years, and in 2009 he founded Jamaa Al-Yad Collective. From January to June, 2016, he was a research fellow at the Asfari Institute of Civil Society and Citizenship, focusing on concepts of citizenship as applied to the displaced, dispossessed, and disinherited. He was recently a resident printmaker at the Newark Print Shop in New Jersey, and currently works as an assistant professor of illustration at Emily Carr University in Vancouver, Canada.

Links:

- Jamaa Al-Yad

- Booklyn

- Jewish Voices for Peace

- Up Against the Wall exhibition

- Imaging Apartheid

- Celebrate People’s History: Iraq Veterans Against the War

Images courtesy of Kevin Caplicki and myself.